Unbeknown to the French and the Vietnamese, the whole war had led up to this very point in time at Dien Bien Phu. What followed was not a particularly large battle, but it was to prove decisive. Construction of the central base and headquarters area commenced in late November 1953, but work on the perimeter defences did not start until mid-December.

The initial success of Castor, in terms of securing the base, soon meant that Dien Bien Phu was welcoming high-ranking military and political tourists. These included generals Navarre, Cogny and Lauzin, and even the French defence minister René Pleven. Navarre and Gilles were photographed together at Dien Bien Phu in December. They and the six officers behind them all looked in an ebullient mood.

Foreign visitors included the British High Commissioner, Malcolm McDonald, and the British military attaché, General Spears. Among the Americans, was the U.S. army commander in the Pacific, General John ‘Iron Mike’ O’Daniels. He was a veteran of the First and Second World Wars and had served in Korea as a corps commander. O’Daniels was photographed during his visit and he did not look impressed. Pleven, on the other hand, came away with the right impression.

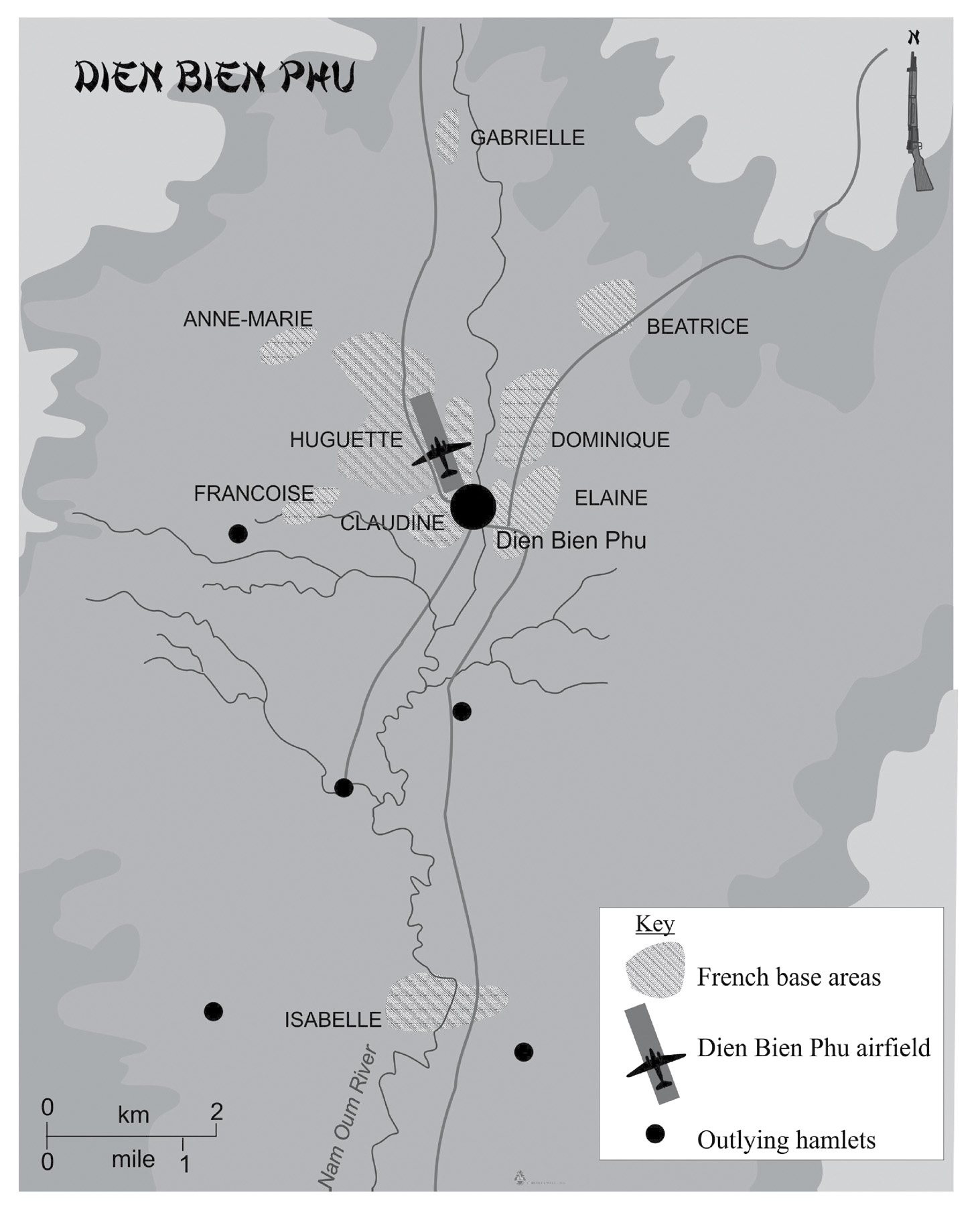

By the new year Dien Bien Phu, had been fortified with eight defensive bastions, forming an outer and inner ring. To the north of the main airfield, running in an arc through the edge of the surrounding hills, were the defensive positions ‘Francoise’, ‘Anne-Marie’, ‘Gabrielle’ and ‘Beatrice’. Gabrielle to the far north was the farthest from the main base. In the centre of the village was the command HQ, with the inner ring comprising ‘Huguette’ to the northwest of the main airfield, ‘Dominque’ to the east, ‘Claudine’ just to the south, and ‘Elaine’to the southeast. The most isolated outpost was ‘Isabelle’, built below the smaller airstrip and some 6.5km from the main base area.

Anne-Marie, Gabrielle, Beatrice and Elaine were built on the lower hills on the fringe of the valley. The rest were largely on the flat valley floor. During a visit, General Navarre had expressed concern that Beatrice, built on a high hill, was isolated, and that if it was captured, it would enable the enemy to overlook the entire base area. He was reassured that if ever this should happen they would be blasted off by the artillery.

Despite any reservations he may have had, General Navarre, having made his decision to fight, poured men and equipment into the valley to ensure that it was the rock upon which the Viet Minh tide would be broken. During December 1953 and January 1954, infantry, armour and artillery units streamed into Dien Bien Phu by air. The garrison at this stage numbered around 10,800 men, backed by two groups of artillery with 75mm, 105mm and 155mm guns, 10 M24 Chaffee light tanks, and 9 Bearcat fighter bombers, stationed on the main airfield.

Viet Minh spies watched with interest as the French set about building their defences across the valley floor. The constant drone of transport aircraft indicated that a major French build-up was underway. From the end of November 1953 through January 1954, an average of 165 tons was delivered every day. It was evident from all the activity to the north around the airfield that this was the focus of the French fortifications, and was therefore where the weight of the Viet Minh assault would take place. Just before battle commenced, Giap had detected ‘forty-nine strong-posts, group into three main sectors [around the airfield] capable of supporting each other’.

Many of the French paras, including the 2nd Battalion, 1st Parachute Light Infantry Regiment, 1st Colonial Parachute Battalion and the 5th Vietnamese Parachute Battalion, were withdrawn to act as a mobile reserve. Only the legionnaires of the 1st Para Battalion and the 8th Para Shock Battalion remained. The others were replaced with more heavily armed infantry units and four battalions from the Foreign Legion that included the 1st and 3rd battalions from the 2nd and 3rd Foreign Legion infantry regiments respectively, and the 1st and 3rd battalions of the 13th Foreign Legion Demi-Brigade.

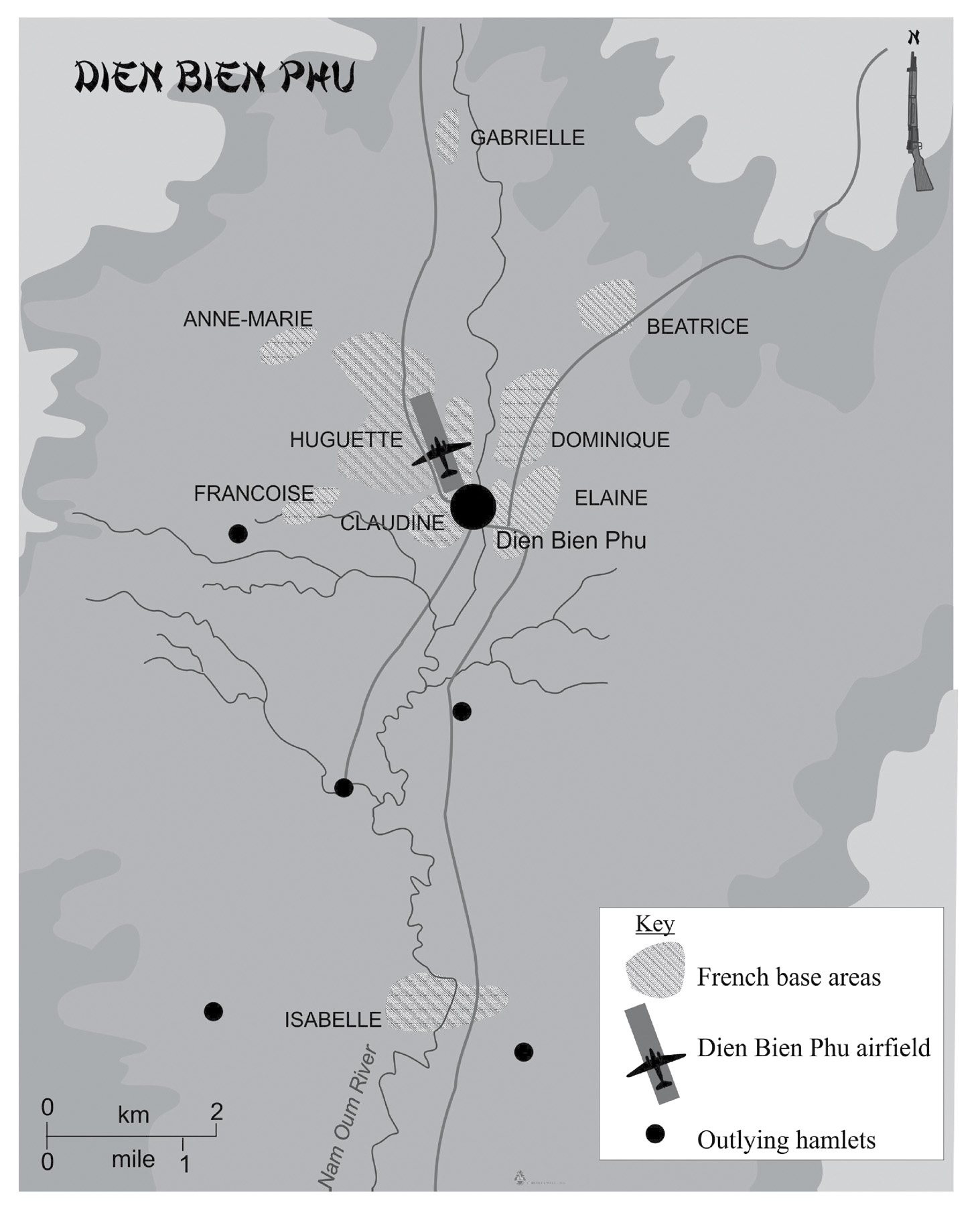

Vietnamese troops digging trenches near Dien Bien Phu’s main airfield.

The French showed great ingenuity in getting some of their heavier equipment to the base. When base commander Colonel de Castries requested a squadron of tanks, this posed a particular problem as they were simply too heavy to air drop. The U.S.-built Chaffee tanks had to be dismantled and flown into Dien Bien Phu. Each 18-ton tank was broken down into 180 parts that took six C-47 sorties and two by British Bristol 170 freighters, requisitioned from a commercial Indochinese airline, to deliver. The latter were the only aircraft capable of taking the tanks’ hulls. Foreign Legion mechanics reassembled the Chaffees beside the main runway, completing one every two days. Similarly, each 155mm howitzer needed two C-47s and one Bristol 170, plus another seventeen C-47s for the gun crews and ammunition.

The garrison was also bolstered by six battalions of colonial troops, consisting of the 2nd battalion, 1st Algerian Rifle Regiment, the 3rd Battalion, 3rd Algerian Rifle Regiment, the 5th Battalion, 7th Algerian Rifle Regiment, the 1st Battalion, 4th Moroccan Rifle Regiment, plus the 2nd and 3rd T’ai battalions.

Artillery units included the 2nd and 3rd artillery groups, the 4th and 10th colonial artillery regiments, and the 1st Foreign Legion Airborne Heavy Mortar Company. The tanks served with the 1st Light Horse Regiment.

The French air force and navy were called on to support Dien Bien Phu. They operated from four main airfields dotted around Hanoi: Bach Mai to the north, Gia Lam to the east, and Don Son and Cat Bi to the south. Notably, the Flying Boxcar transports of Armée de l’Air flew from Cat Bi. The F4U-7 and AU-1 Corsairs of the Navy’s Flottille 14F flew out of Bach Mai. The air force was able to provide two fighter squadrons, two bomber squadrons and four squadrons of transports. Naval aviation comprised two dive-bomber squadrons and a bomber squadron.

A squadron of French Bearcats was deployed to Dien Bien Phu to provide air-to-ground support.

Despite this impressive order of battle, it was nowhere near the strength committed to Operation Loraine. Unlike previous French fire bases, the widely dispersed defences at Dien Bien Phu were far from perfect. It was likened to an idyllic death trap. The picturesque valley was simply too large for a tight all-round defence and too small to manoeuvre in. Notably, the surrounding hills that rise up to 2,500ft easily dominated the principal 1,200yd airfield. The engineers calculated that they required 36,000 tons of equipment – total deliveries for the entire battle only amounted to 22,500 tons. This would have required 12,000 C-47 Skytrain flights from Hanoi. All they received was a third of this tonnage and three-quarters of the deliveries were barbed wire. Here lay part of the cause for the French defeat, because the fortifications were not capable of withstanding an artillery barrage.

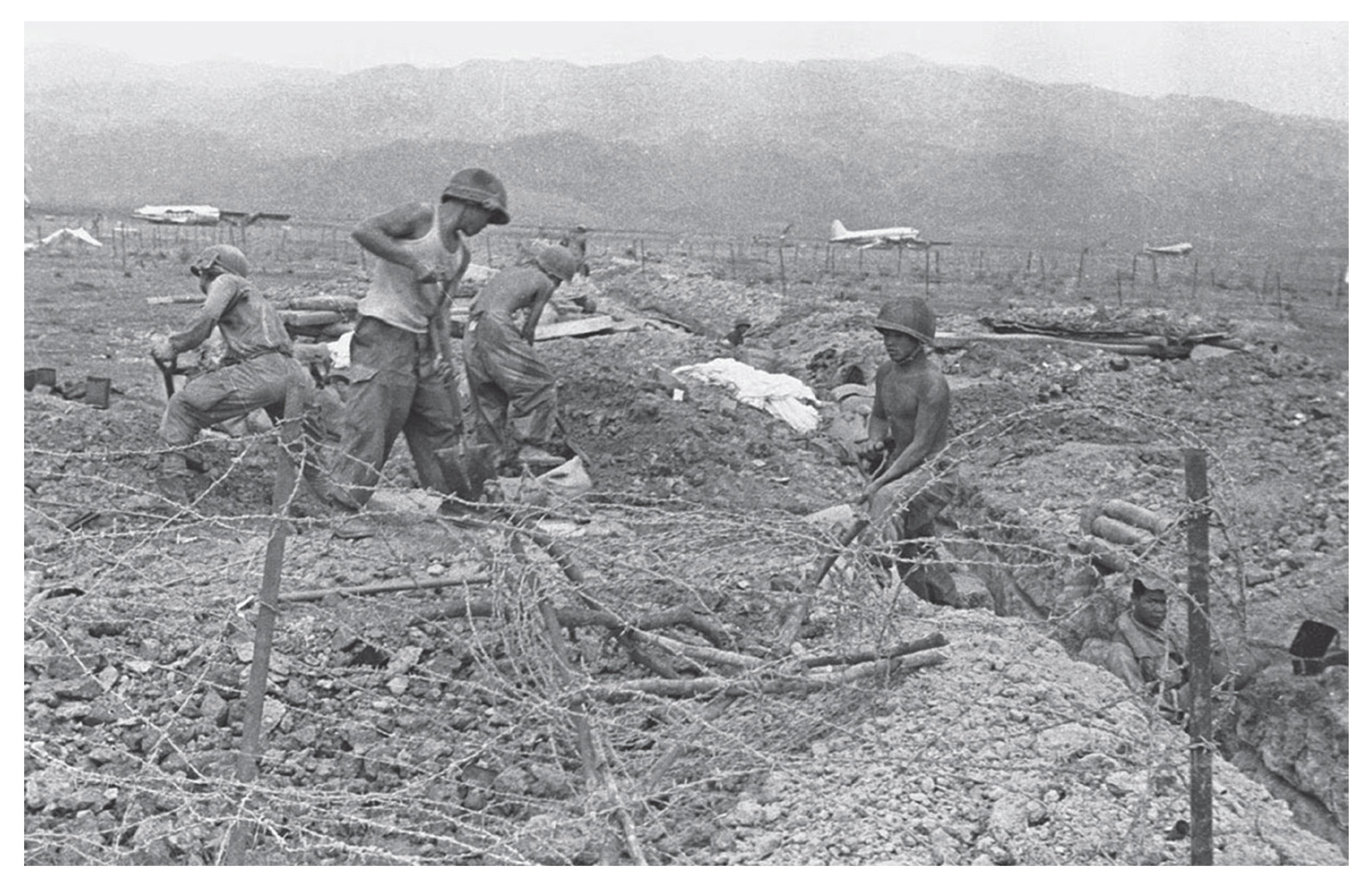

To protect the base, Colonel des Castries had just twenty-four American 105mm howitzers, four short-barrelled 155mm howitzers, and thirty-two 120mm heavy mortars. The one-armed Colonel Charles Piroth, commanding these units, considered them more than capable of breaking up enemy attacks. They would provide effective counter-battery fire when the time came. Piroth also thought that the air force operating from the airfield and the delta would pounce on any enemy guns once they started firing. He was completely contemptuous of Giap’s gunners, claiming, ‘No Viet Minh gun will fire three rounds without being destroyed.’

French troops supported by a Bison light tank.

This was a fatal miscalculation. His batteries were poorly protected. The guns were placed in large circular pits that were very vulnerable to indirect shell and mortar fire.

Piroth, who had lost his left arm in Italy in 1943, was an experienced gunner. Despite his outward confidence, however, he knew his resources were inadequate, pointing out to Colonel de Winter, his superior in Hanoi, that he had fewer artillery pieces than that normally supporting an infantry division. The location of Isabelle particularly hamstrung Piroth’s artillery. By the end of January, two batteries had been deployed there, but these were too far away to offer any support to the northern strongpoints. In addition, Piroth’s guns relied on observation posts in the hills and six light observation planes. Once the shooting started, these would be lost very quickly. The result was that his gunners would be reliant on spotter planes making a three-hour trip from Muong Sai in Laos.

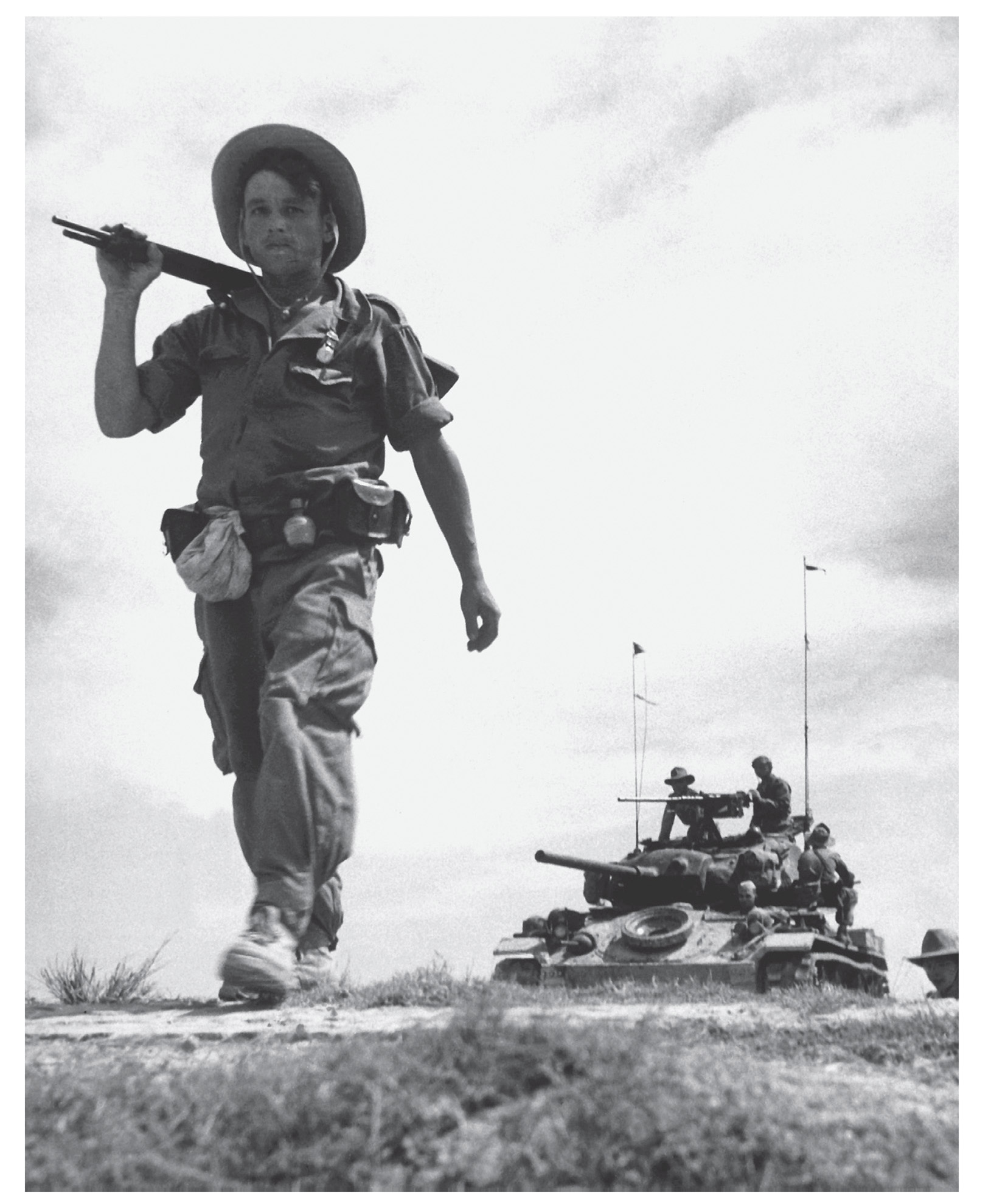

Concealed in the dense jungles around Dien Bien Phu, Giap and his Chief of Staff, General Hoang Van Thai, began gathering their 304th, 308th, 312th, 316th and 351st divisions, amounting to over 50,000 men. As the latter unit was organized as a heavy division, it had a bigger provision of artillery and mortars, with at least thirty American 105mm (captured in Korea) and eighteen, largely Japanese, 75mm guns, fifty 120mm heavy mortars, and sixty 75mm recoilless guns. Of equal importance, it had an anti-aircraft regiment armed with thirty-six 37mm anti-aircraft guns.

In total, including the artillery battalions serving with the other divisions, Giap had about 145 field howitzers. By early March, he had available some 15,000 105mm and 5,000 75mm shells. Two thirds of the 105mm ammunition was already in the Dien Bien Phu area. However, the Japanese 75mm Type 94 mountain gun was obsolete and much of its ammunition was a decade old.

Once again, the hand of Mao, in the form of General Wei and his advisers, was evident. The Chinese Communists had ample experience with the American M2 A1 105mm howitzer, which had been captured in quantity during the Chinese Civil War and the Korean War. This weapon could drop four high-explosive rounds a minute onto a target up to a range of over 11,000m. According to Giap, the 351st Division received around fifty 105s from the Chinese, most of which had been taken in Korea, and that thirty-six were deployed at Dien Bien Phu. Most of these weapons had presumably been captured from the South Korean rather than the U.S. army.

Equally important was the training his gunners of the 45th Artillery Regiment received on these weapons in southern China. Once they were outside the French base, they ensured their 105s were well dug in and concealed from the air. Dummy guns were also deployed to draw French fire. Artillery observers, with uninterrupted views of the airfield and French defences, took up position to accurately direct the gun fire.

The Viet Minh hacked five routes through the jungle toward the French base. As well as tens of thousands of porters on foot and using bicycles to shift supplies, Giap’s men had 600 Russian-built 2.5-ton lorries, which travelled by night with their lights off to avoid attracting attention. Nonetheless, the weather and French air force together conspired to ensure that this build-up did not run smoothly. The torrential rains turned the valleys into marshes and many fords were impassable. French pilots attacked the Lung Lo and Phadin passes, resulting in sections of the roads sliding into the ravines below.

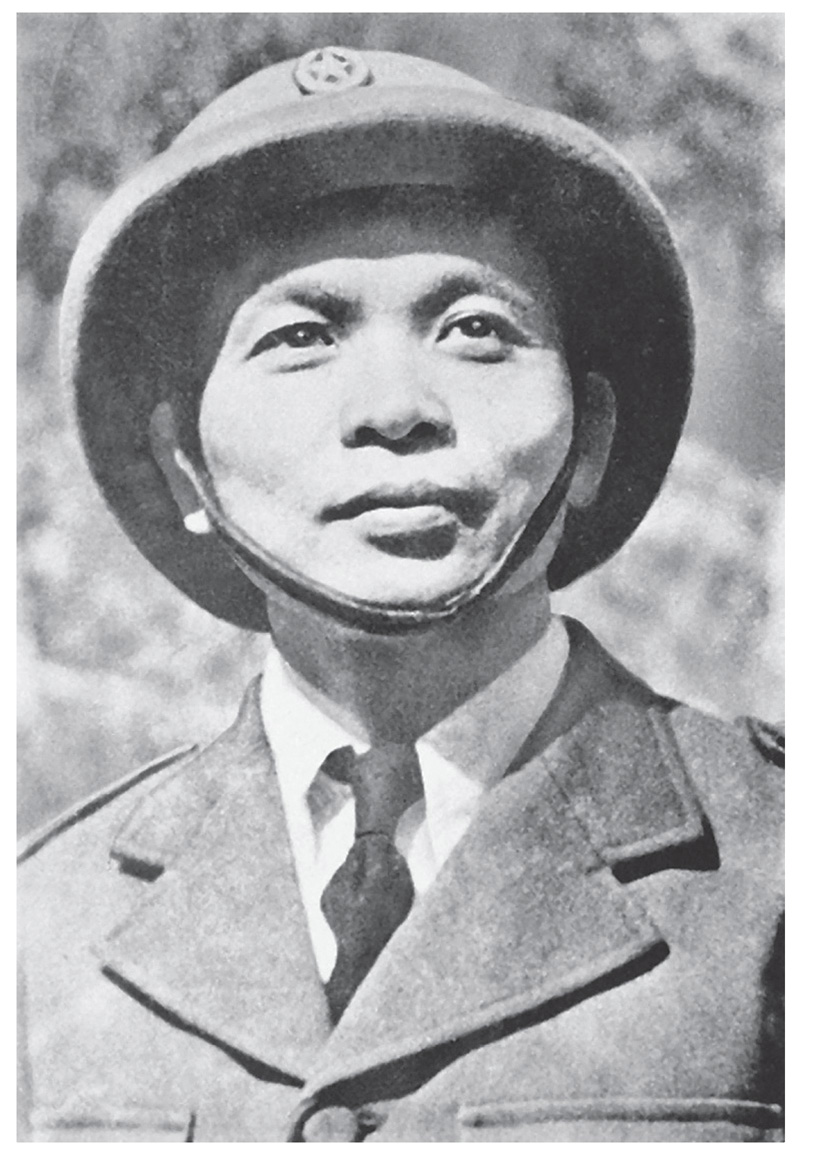

General Giap.

The French were not ignorant of the Viet Minh build-up, as their air force had detected the movement of men and equipment. By early December, it was estimated that Giap would have about 49,000 men under his command. Aerial intelligence also showed that Giap’s 105s had been removed from their rear-base areas. A sizeable attack on Dien Bien Phu was now inevitable.

Giap’s logistical support comprised tens of thousands of porters.