Giap officially let his presence at Dien Bien Phu be known on 31 January 1954 when his artillery opened fire. They spent six long weeks making and adjusting ranging shots across the base. While the French found it increasingly bothersome, Giap slowly collected very important targeting intelligence. Throughout February, French patrols kept detecting Viet Minh regular units, confirming that Giap had taken the bait and was prepared to fight.

By the middle of the month, any plans to stretch the French defences out to encompass the higher surrounding hills had been abandoned. By doing so Colonel de Castries surrendered the initiative and the vital high ground to Giap. De Castries did not have the manpower to create a wider perimeter, but he should have done his utmost to disrupt the Viet Minh preparations. Instead, he settled back to await Giap’s first attack.

General Navarre paid his last visit to the base on 4 March 1954, during which he discussed with de Castries bringing in reinforcements. The general was clearly rattled by the strength of the force Giap had brought to bear on the valley.

‘I was much less confident than the local commandant,’ said Navarre. ‘I thought of suddenly bringing in three additional battalions – and since the Viet Minh were very methodical I thought they would then think twice.’

De Castries reassured him that they were not needed and should be kept in reserve. ‘That is what I did,’ recalled Navarre, ‘I was probably wrong.’

During November and December, the valley was verdant and dotted with trees. By early March, it had been turned into a desolate lunar landscape. The trees had been hacked or blasted down and the banks of the Nam Youm River stripped bare. The central headquarters area on the west bank was a mass of bunkers, earthworks, trenches and revetments. Just to the north were the gun pits for some of the 105s and the 155s. Beyond them were aircraft dispersal pens created by banked earth.

French machine-gunners awaiting attack.

Both sides knew that the fighting would commence to the north. It was the Algerian garrison of Gabrielle that sustained the first probing attacks on 11 March. Giap had a choice to either take Gabrielle or cut it off by capturing Anne-Marie and Beatrice to the southwest and southeast. It was decided to attack all three. However, looking at their maps, Giap and his divisional commanders decided that Beatrice, consisting of four strongpoints that were out on a limb, would be their next main target. The battle of Dien Bien Phu was about to start in earnest.

Colonel de Castries knew roughly where the blow was to fall. The following day, he briefed his commanders to expect an attack on the 13th at 5.00 pm. His suspicions were confirmed when Viet Minh movements were detected in the area of Beatrice and Gabrielle, after two regiments from the 312th Division moved into position less than 100yd from the French defences. The vulnerability of the main airfield and the airstrip near Isabelle were soon illustrated when artillery fire ranged in from 9.00 am on 12 March, destroying two C-47s, while others were riddled with shrapnel on the taxiways or as they tried to come in to land.

Just two Bearcats were serviceable that day, the rest having been damaged by the hail of hot shell fragments. They managed ten sorties between them, buzzing angrily around the valley looking for somewhere to drop their 500lb bombs. The fighter and transport pilots found themselves attracting increasing anti-aircraft fire from machine guns, 20mm cannons and 37mm AA guns concealed beneath the dense hillside foliage. Six Hellcats flying from the carrier Arromanches tried to help suppress the flak, but struggled to find their targets and futilely bombed the same locations. Unable to get back to the carrier, one of the aircraft crashed trying to find Cat Bi airfield.

At 5.15 pm on 13 March, Giap’s 105s began to drop shells onto Beatrice for the next two hours. It was a shocking taste of things to come. Communication trenches were blasted into oblivion, inadequate gun positions and bunkers collapsed. Deadly flying debris and shock waves killed or wounded anyone caught in the open. French counter-battery fire proved wholly ineffective. Beatrice lost two 105mm guns to enemy artillery fire. The French, in a desperate attempt to protect the three northern outposts, wastefully fired off 25 per cent of their 105mm ammunition in one night. Lieutenant Colonel Jules Gaucher, the post commander, and the men of Major Paul Pégot’s 3rd Battalion, 13th Demi-Brigade of the Foreign Legion, braced themselves for the inevitable.

While Beatrice and the airfield were being bombarded, shells also fell on Gabrielle, Dominique and Isabelle. On the airfield, accurate shelling took out the VHF radio beacon, damaged the temporary control tower and blew up two Bearcats. At Dominique, a heavy-mortar platoon, just about to provide counter-preparation fire on the Viet Minh’s assembly trenches before Beatrice, was pulverized by a direct hit on one of the weapon pits. Then their ammunition dump containing 5,000 mortar bombs exploded in a brilliant ball of flames. The garrison of Gabrielle was also prevented from providing supporting fire to Beatrice by a series of diversionary attacks.

Crawling forward from their assault trenches, at 6.15 pm, brave Viet Minh sappers blew holes in the remaining barbed wire around Beatrice. Fifteen minutes later, just as their infantry opened the assault, Beatrice’s battalion command post received a number of direct hits. Pégot was killed and Gaucher mortally wounded. Despite losing their senior officers, the legionnaires engaged in desperate hand-to-hand combat as the Viet Minh sought to overwhelm them. By 9.00 pm, just one strongpoint was still holding out. Three hours later it was all over.

Troops of the 1st Foreign Legion Heavy Mortar company who fought at Dien Bien Phu.

The garrison suffered 75 per cent casualties with just over 100 men escaping back to their lines. Giap’s artillery stopped firing and a stunned silence fell over the valley. The stench of explosives hung in the air.

Colonel de Castries was shocked that Beatrice had held for just six hours. If Giap could repeat this success, then Dien Bien Phu was unlikely to last much more than a week. In the early hours of 14 March, he reluctantly reported to Cogny in Hanoi that he had lost a battalion and Beatrice. This was at a cost of around 125 dead and some 200 captured, most of whom were wounded. As Giap had intended, Gabrielle was now extremely isolated, and the 88th and 165th regiments from the 308th and 312th divisions moved into position ready to strike.

General Navarre was dismayed by the incoming reports of the strength, accuracy and closeness of the Viet Minh guns:

All the French and American artillerymen who had visited Dien Bien Phu – and there were many Americans – thought that the Viet Minh would have to stay behind the ridges to fire on the entrenched camp. The surprise was that they managed to bring their artillery much closer than we had thought possible.

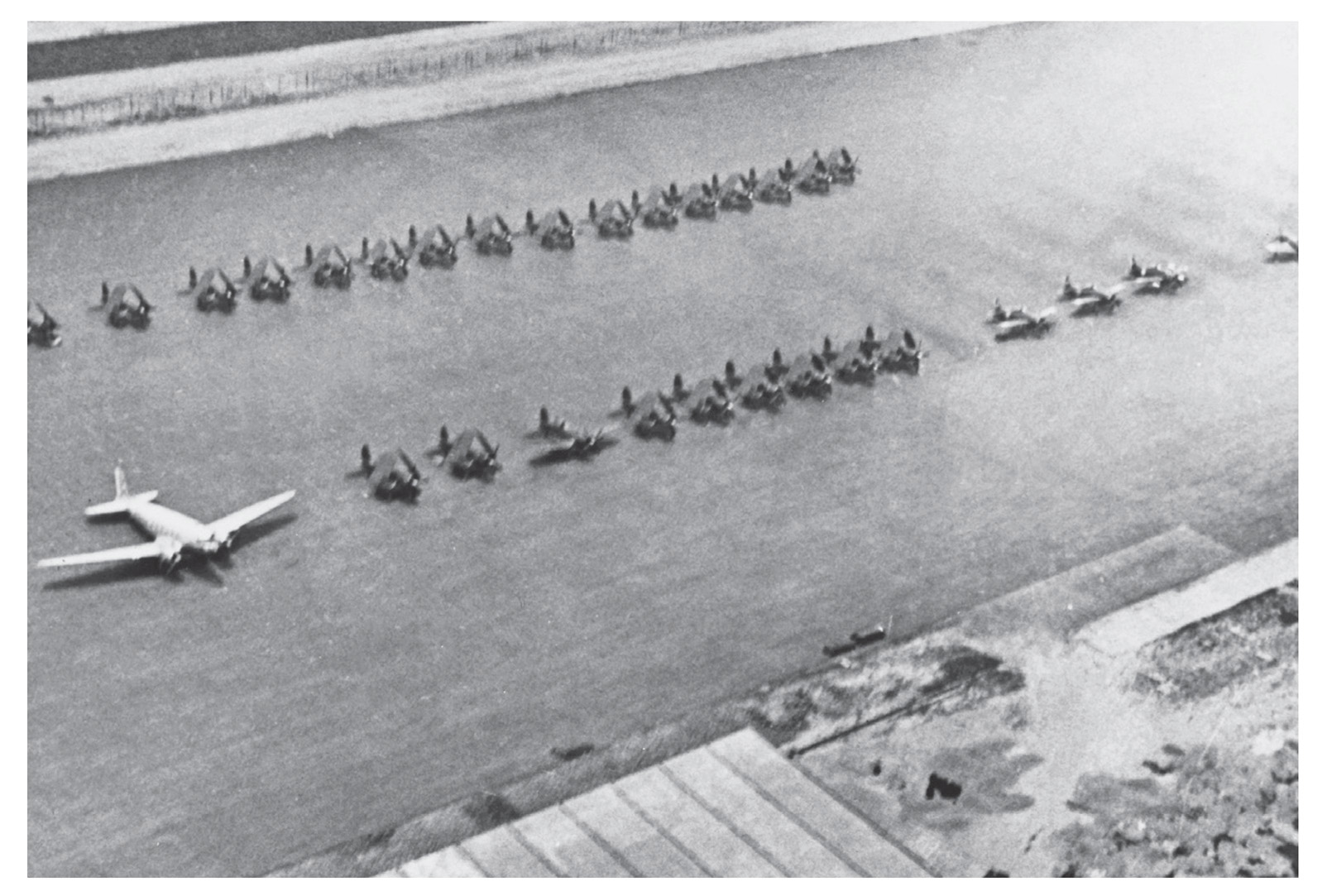

Tourane airfield, in 1954, showing 25 Vought F4U-7/AU-1 Corsairs, four Grumman F8F Bearcats and a solitary Douglas C-27 Skytrain.

On 14 March, French reinforcements arrived in the form of a para drop by the 5th Vietnamese Parachute Battalion, commanded by Captain Botella. De Castries briefly contemplated trying to retake Beatrice, but low cloud and poor weather made close air support impossible. At 6.00 pm, Giap’s batteries began shelling Gabrielle, which was held by a battalion of Algerians with eight Foreign Legion 120mm mortars. Although they beat off the first assault, by dawn on the 15th, they were only holding on in one remaining outpost.

Lieutenant Colonel Trancart, who was in charge of the northern sector, was watching the heavy shelling of Gabrielle when a distraught Colonel Piroth came into his dugout.

‘I am completely dishonoured,’ cried Piroth. ‘I have guaranteed de Castries that the enemy artillery couldn’t touch us – but now we are going to lose the battle.’

The admission that no one wanted to hear, or acknowledge, was true.

Lieutenant Colonel Langlais organized a counterattack towards Gabrielle, employing two companies of legionnaires and one battalion of Vietnamese paratroopers, supported by six tanks. They fought their way to within 1,000yd of the Algerians, enabling 150 men to escape to safety. De Castries had lost his second outlying strongpoint in just two days. Within the garrison there was a sinking feeling that after all their efforts in building the base’s defences, perhaps Dien Bien Phu was untenable.

Unfortunately for them, generals Navarre and Cogny were not Leclerc or de Lattre – both the latter would have quickly taken firm control of the situation and sought a solution to safeguard the garrison. Indeed, neither of them would have ever dreamed of underestimating their enemy and extending French forces in such a manner. The uninspired de Castries seemed to slip into an ever-deepening despondency, while Navarre and Cogny strove to blame each other for the unfolding mess.

Even at this early stage in the battle, everyone at senior level was preparing for a worstcase scenario. The French had the decisive conventional battle they had always hoped for, but they were already losing. They had realized too late that Dien Bien Phu was simply too damn far away. The agony, though, was only just beginning. In Saigon and Hanoi, the only solution was to belatedly send in the paras to beef up the defences. They could come up with no other options.

Langlais, commander of the Airborne Battle Group 2, was furious at how the action was progressing. De Castries was a reflective-looking man, whereas Langlais was wiry, gaunt and tough in appearance. He never seemed to be without a cigarette firmly clamped between his lips. Langlais was described as hatchet-faced, while de Castries was dubbed aloof and highly aristocratic.

Although de Castries lacked neither courage nor panache, he was overwhelmed by unfolding events and did not have the ability to control a battle of this magnitude. To be fair however, he was operating way above his pay grade. He was commanding a division-sized operation that required a general. The French, though, always ran these types of operation employing a colonel, for fear of losing someone more senior. If anyone should have been in command, it was Brigadier General Gilles as the ranking officer.

The angry Langlais took his wrath out on Piroth, whose pledge to silence Giap’s guns had come back to haunt him. Despite their best effort, his gunners and the French air force had singularly let down the garrison. Feeling dishonoured and ashamed, on 15 March, while in his quarters, Piroth took a hand grenade and pulled the pin using his teeth. His death was hushed up for fear it would harm already poor morale.

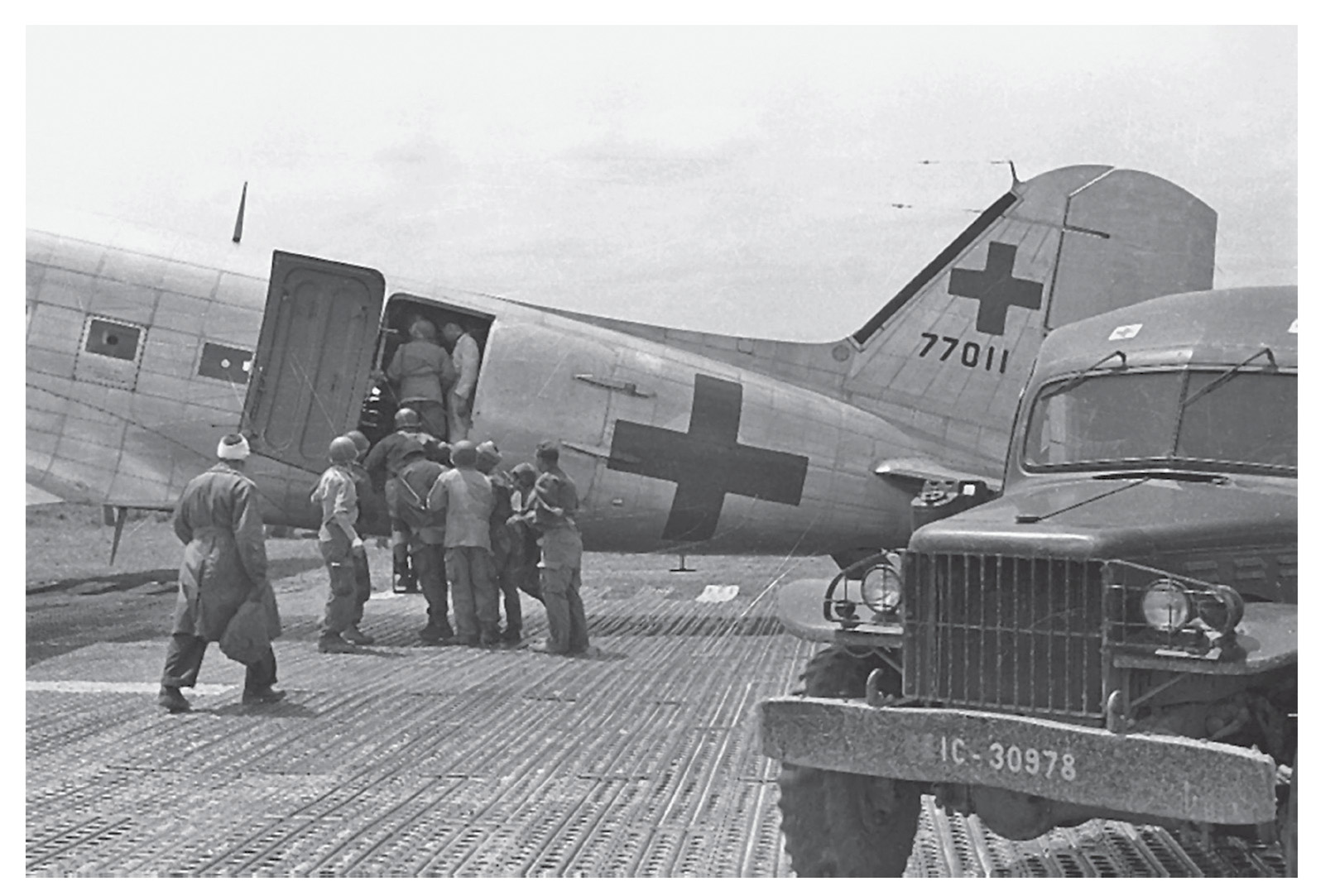

French wounded being evacuated.

French trenches at Dien Bien Phu.

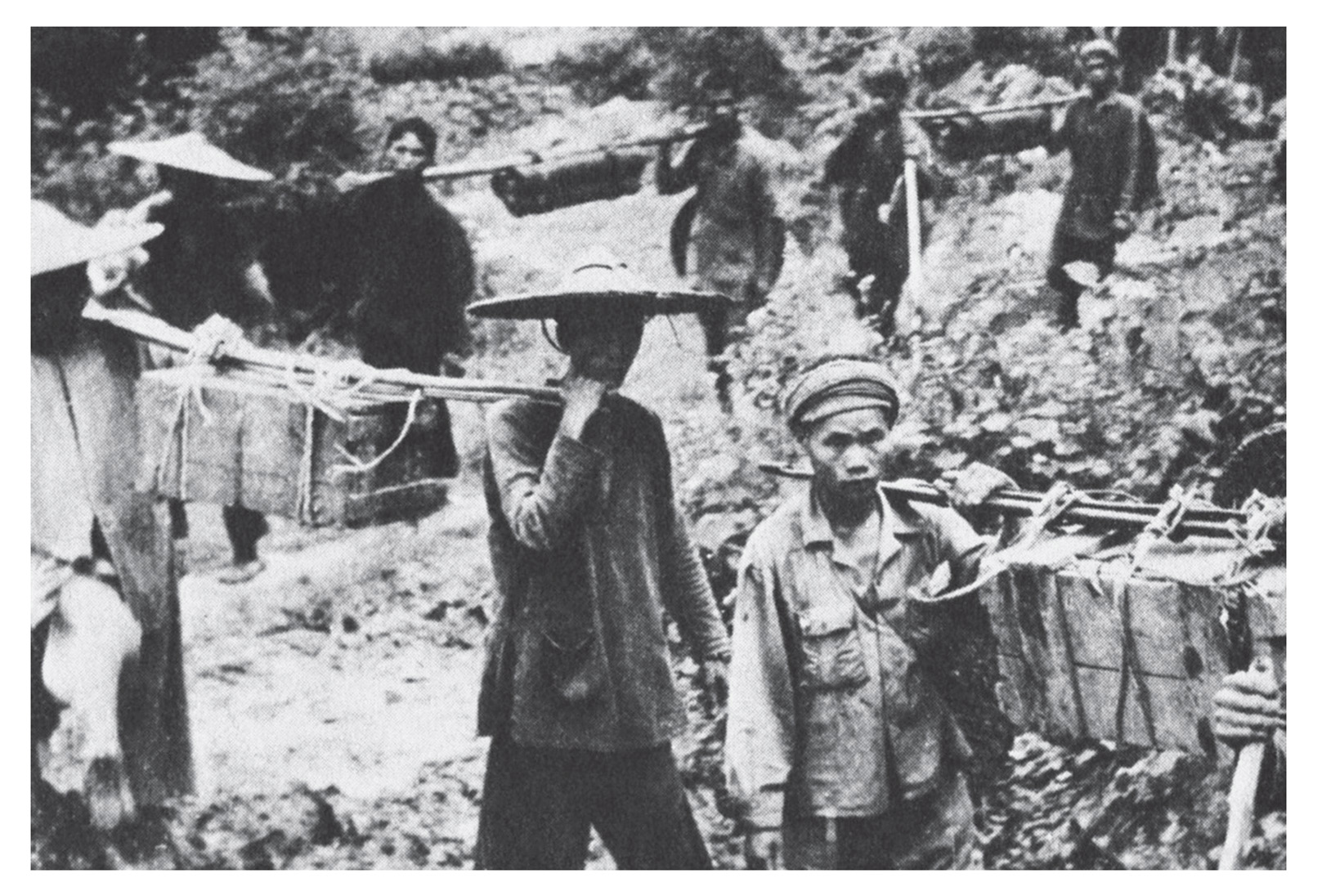

Giap’s logistical support comprised of tens of thousands of porters.

When Bigeard was informed of Piroth’s death he said:

I had known him as a man of duty and heart who had said that as soon as a Vietnamese cannon was found he would overpower it. But they were invulnerable. We could fire 100 shots on their positions and still be incapable of destroying their cannon. Giap had attacked only when he felt that everything was just right.

The following day, the mood lifted slightly when Major Bigeard and his 6th Colonial Parachute Battalion dropped back into the valley. From 14 March to 6 May, the French parachuted and air-landed 4,300 men to reinforce the base. This boost, however, was short lived, as the 3rd T’ai Battalion holding Anne-Marie knew that they would be next in the firing line and have to abandon their posts. Two companies fled from two of Anne-Marie’s four positions. A third of Dien Bien Phu’s defensive bastions had now fallen.

In Hanoi, General Cogny was anxious about the situation in the Red River Delta. Intelligence showed that the Viet Minh could muster thirty-nine battalions, of which twenty-four were regulars. Their key units were the reconstituted 320th Division and six regular, independent regiments. Additionally, they had some 50,000 communist militiamen. Cogny had at his disposal around 100 battalions, less than a third of which were mobile, and of them, just sixteen were in the mobile groups. He was also concerned that Navarre was persisting with Operation Atlante in southern Vietnam, which was tying up sizeable forces. The bulk of these, however, were ineffectual Vietnamese troops who were proving that Navarre’s ‘Vietnamization’ process was not working.