U.S. Navy LST 516 loading refugees at Haiphong, 1 October 1954.

The repercussions of Dien Bien Phu were swiftly felt around the world.

Charles de Gaulle had always been adamant that the loss of Indochina would spell the end of the French empire. He was soon proved right. It spelt not only the beginning of the end for the French Union, but also the Fourth Republic. In Paris, Prime Minister Joseph Laniel’s short-lived government fell. He was succeeded by Pierre Mendés-France, who had been a regular opponent of the war in Indochina. He headed for the stalled peace talks in Geneva that were dealing with the troubled issues of Indochina and Korea. The British and Americans tried to support Mendés-France, but there was little to be salvaged from the situation.

Only Ho Chi Minh’s powerful allies kept him in check from exploiting his victory even further, but he was prepared to bide his time. China proved a stumbling block to the Viet Minh dominating all of Vietnam, north and south. The Soviets, alarmed at the prospect of the Chinese expanding the war throughout Southeast Asia, applied pressure on Chinese Foreign Secretary Chou En-lai. The Chinese, however, had their own agenda, which had been set well before Dien Bien Phu and the Geneva Conference.

Mendés-France and Chou met on 23 June 1954, without the Vietnamese present, to cut a deal. The terms were not what Ho and his comrades had fought for all those years. When Chou saw the Viet Minh delegation he warned, ‘If the Vietnamese continue to fight, they will have to fend for themselves.’

Mao made it clear that if Vietnam’s communists continued the war, he would cut off all military support. Pham Vam Dong, Ho Chi Minh’s negotiator, was instructed to concede. It was a bitter blow, for it meant the Viet Minh in the south were to give up the struggle.

‘I travelled by wagon to the south,’ recalled Le Duan, who later became Vietnam’s leader. ‘Along the way, compatriots came out to greet me, for they thought we had won a victory. It was so painful.’

Nonetheless, Indochina’s nationalists achieved almost all their goals with the Geneva Accords of 21 July 1954. Cambodia and Laos had their independence recognized, while Vietnam was divided along the 17th Parallel. This created a formal ceasefire line, which accepted communist control of the north but not the south. Washington was far from happy with this latter concession. To some, it looked like Korea all over again.

British intelligence in March 1954 had accurately forecast the likely scenario if the French were defeated at Dien Bien Phu, stating:

The Soviet Union and China may be prepared to see an end to the fighting provided that the future of the Viet Minh were assured, either by coalition or partition, but they are unlikely to abandon the Viet Minh in return for any concessions in other fields that we could afford to offer …

Ho Chi Minh returned triumphant to Hanoi as the leader of the new Democratic Republic of Vietnam, consisting of Tonkin and northern Annam. In Saigon, Ngo Dinh Diem formed the pro-Western Republic of South Vietnam from Cochinchina and southern Annam.

The French agreed to withdraw their forces from the north, while the Viet Minh reluctantly withdrew from the south.

The immediate headache for the French was that the Geneva Accords allowed for a 300-day period of free movement between the two Vietnams. Upwards of a million northerners, including around 200,000 French citizens and troops, wanted to move south, while about 150,000 civilians and Viet Min fighters wanted to go the other way. It was an enormous mass movement, with people travelling by land, air and sea. The French navy and air force shifted the bulk of them, though they were also supported by the U.S. Navy.

After Dien Bien Phu, neither the French had the stomach to continue the fight in South Vietnam, nor were the South Vietnamese keen on them staying. The French defence budget was exhausted. In Paris, there was unease that nationalist unrest might break out in France’s other colonies, which had long held aspirations of independence. At the end of the Indochina War, the French Expeditionary Corps, numbering approximately 140,000, faced a swift reduction. It was cut to just 35,000 by mid-1955, with many of those withdrawn sent to Algeria. Tellingly, the French military budget for the following year made no mention of Indochina.

America, which from the start had said it would not support British and French colonialism, had nonetheless assisted the French in Indochina. Washington had committed over a billion dollars, two-thirds of which was on equipment delivered straight to the French Expeditionary Corps. The American armed forces, however, had no say in how it was used or what happened to it. President Eisenhower refused to sign the Geneva Accords and moved to support the South Vietnamese army.

By December 1954, formal agreement had been reached between America, France and the Republic of Vietnam for the U.S. to provide aid through its military assistance programme. This included provision for a drastically reduced South Vietnamese armed forces of 100,000 and a joint Franco-American training mission. At the time of the armistice, the Vietnamese armed forces stood at some 205,000 men. These were largely infantry under French officers and non-commissioned officers. When the troops were redeployed from North to South Vietnam, desertion became a major problem. In addition the Vietnamese had no real experience of military logistics, having been dependent on the French for so long.

Tragically, the French desire to be rid of Indochina as quickly as possible sowed the seeds of the Second Indochina War – better known as the Vietnam War. By this stage, trouble was brewing in French North Africa. The French military, understandably, set about cherry-picking the best equipment from Indochina. American personnel were forbidden access to French bases and depots, which meant that they had no idea what was available to the Vietnamese. The French simply took vast quantities of equipment with them, some of it that had been supplied to the Vietnamese under the military assistance programme.

The intention was to ensure that the South Vietnamese forces had full logistical independence by January 1956, but this never happened, nor was it ever really achievable. As the final French withdrawal approached, they dumped tons of old and poorly maintained military materiel on their former Vietnamese allies who did not know how to handle it properly, and containers were opened and piled randomly out in the open. The last French troops left Vietnam on 28 April 1956, having decided that Indochina was no longer their problem.

Washington soon came to the conclusion that in light of the build-up of the Vietnamese communist forces in the North, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam should be maintained at 150,000 strong. Following the departure of the French and the dissolution of the joint training mission, Washington had no choice but to increase its military advisers and its military commitment to South Vietnam. The Cold War was far from over in Southeast Asia.

U.S. Navy LST 516 loading refugees at Haiphong, 1 October 1954.

Predictably, Ho’s government announced in December 1960 that the Viet Minh would resume their operations to liberate South Vietnam. In response, President John F. Kennedy sent 686 military advisers to organize the South Vietnamese army, which was to be expanded by 20,000 with American assistance. Slowly but surely America was dragged into the conflict between the two Vietnams.

Ironically, the presence of the Americans ensured China and the Soviet Union did all they could to support Hanoi’s desire for unification. In 1968, the U.S. military found itself facing its own Dien Bien Phu at a place called Khe Sanh. On this occasion, though, it was not the main focus of General Giap’s massive Tet Offensive. Although Khe Sanh was not overrun and Tet was defeated, the long-term effect was the same.

Further afield, Dien Bien Phu caused an unwelcome chain reaction throughout the French Union. The impact of the French defeat was immediately felt in France’s most prized colonial possession – Algeria. The French had always deluded themselves that it was part of metropolitan France. This was a fiction perpetrated to legitimize France’s long-standing colonial presence. On VE day in May 1945, an anti-French Muslim demonstration in the Algerian town of Sétif culminated in over a hundred Europeans being butchered. In the weeks that followed, in an orgy of revenge, 6,000 Muslims were killed. Internationally, these events were largely ignored thanks to more pressing matters in Indochina. The Algerians, though, did not forget.

There was also growing unrest in France’s other two North African territories: Morocco and Tunisia. These though were protectorates and France had no right to cling to them. During the Indochina War, French units were deployed in both countries. Between 1952–54 these were drawn from Algeria and, afterwards, from forces returning from Indochina. Algeria and Algerian troops had played a key role in Indochina. In particular, the country had provided an enormous training and transit facility. The French military had some 60,000 troops in Algeria, but less than a third were deployable, while two-thirds of them were Muslim colonial forces. To counter any trouble, the French only had about 3,500 combat troops available. It was not enough.

In November 1954, Algerian nationalists began their first coordinated attacks on French military and police installations. The violence soon spread. France could not, and would not, walk away from Algeria, not when it was home to 1.2 million Europeans. Just as importantly, in 1954 oil was discovered in the Sahara, which convinced the French that Algeria was economically vital. Ironically, even French Communists were largely indifferent to Algerian nationalists. They had no desire to support Algerian independence if it was to the detriment of the prosperity of the French working class.

Two years later, Morocco and Tunisia gained independence and the French garrisons withdrew. The two countries inevitably provided safe havens from which Algerian nationalists could operate. The withdrawal from Indochina, Tunisia and Morocco hardened French resolve over Algérie Française. This time, the politicians had the full backing of the military. The professional army had learned some very important lessons in Indochina about guerrilla and psychological warfare. Many felt guilty about abandoning their Vietnamese allies, seeing Algeria as an opportunity to avenge Dien Bien Phu and preserve the shrinking French Empire.

By early 1955, the French military had rapidly boosted their Algerian garrison to 74,000 troops. By the summer, there were 105,000. The following year, through the use of reservists, they had expanded their presence to 200,000, vastly more than had ever been committed to Indochina. This doubled by the end of 1956, a number that was to be maintained until 1962 and Algerian independence. By the end of the brutal conflict, French forces had suffered around 25,000 fatalities, having killed 155,000 Algerian guerrillas.

The French also gained valuable experience using helicopters in Indochina and did much to develop helicopter warfare. At the time of Dien Bien Phu, the French Army only had a single helicopter in Algeria. Three years later, they had assembled a force of eighty. By the end of the conflict in Algeria, the French had 120 transport helicopters in-country, capable of airlifting 21,000 men a month.

In France’s sub-Saharan colonies, because the French were focused on Indochina and North Africa, they had allowed a greater degree of devolution. African nationalist energies were expended on each other as they argued over closer association with Paris, loose federation or no relationship at all. By the spring of 1956, the French Union was clearly disintegrating. The associated states had broken free and the African colonies were moving towards self-government. French sovereignty was reduced to only those territories that were ruled as part of France, the old Colonial West Indies, the territories in the Indian Ocean, and troubled Algeria. In 1956, France tried to prove that it was still a world power by joining Britain in the brief Suez War against Nasser’s Egypt. It ended in international humiliation for both.

Britain, with its own colonial problems, watched the French defeat in Indochina with interest. Since 1948, it had been fighting to contain a communist insurgency in Malaya. The opening scenario was very similar to Indochina. Originally armed to fight the Japanese, after the Second World War Malaya’s communists decided to resist the returning British administration. They were, however, largely drawn from the local ethnic Chinese population rather than the Malays and Indians. On 16 June 1948, on two rubber estates near Sungei Siput in Perak, three European managers were murdered. As a result, a state of emergency was declared that would last until 1960.

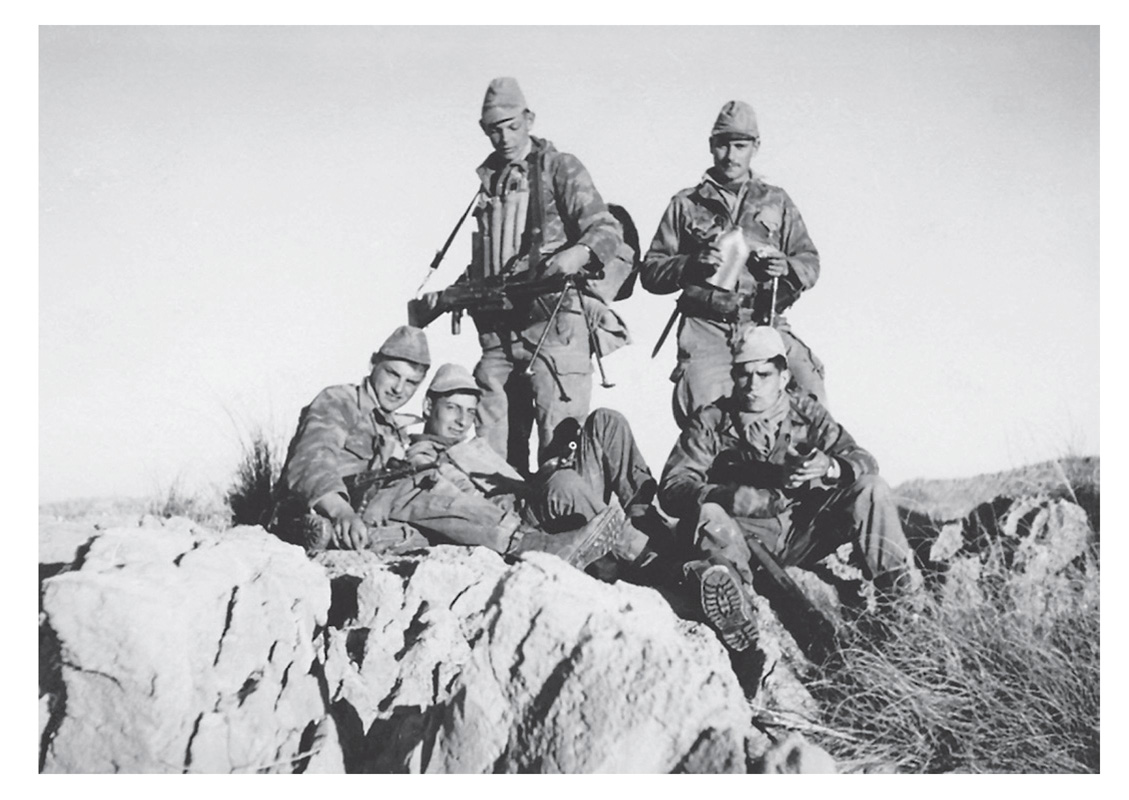

Troops of the Foreign Legion’s 13th Demi-Brigade, Algeria, 1950s.

By 1951, the Malayan Races Liberation Army numbered 8,000, though 90 per cent were Chinese. Until this point they were known as ‘bandits’, but were subsequently dubbed ‘CTs’ or communist terrorists. Fortunately for Britain, support for the guerrillas by China and the Soviet Union was limited. Unfortunately for the Malayan Communists, China was distracted by the wars in Korea and Indochina, which were right on its doorstep. China had no mutual border with Malaya, thereby making it difficult to provide supplies.

To isolate the insurgents, the British adopted a policy of detention and resettlement – especially with Malaya’s Chinese population, which numbered almost two million. At the same time, the British conducted a protracted pacification campaign in the deep jungles and the central mountains. Britain also made it clear that independence would only be granted once the security situation had been restored, but would not surrender the country to the communists. This stance ensured that much of the population continued to support the British presence. This was a situation that the French were never able to replicate in Indochina.

Having gained the upper hand, British forces were keen to avoid the Malayan communists being reinvigorated by the victory at Dien Bien Phu. Between July and November 1954, the British launched their largest operation to date with Operation Termite in Perak, deep inside the jungle east of Ipoh. Also, Operation Apollo was carried out from mid-1954 until mid-1955 in the Kuala Lipis area of Pahang. It was another five years before the Malayan emergency was declared over, by which time the communists had lost 10,684 killed and captured.

To the outside world, Dien Bien Phu confirmed that France was the victim of weak and chaotic government. The Fourth Republic endured twenty-four governments when Britain had four and Germany just one. France remained polarized between the left and the right. The RPF (Rassemblement pour la France) made considerable gains, and although de Gaulle relinquished the leadership in 1953, it was still a powerful right-wing force. On the left, the communist party continued to garner about a quarter of the vote. Continuous war had strained the economy, causing a devaluation of the franc in 1957.

The fallout from Dien Bien Phu brought France to the brink of military dictatorship. While de Gaulle was an ardent supporter of the Union Française, he had little regard for the pro-Algerian element within the army, as they had backed generals Pétain and Giraud against him in 1943. When in May 1958 it looked as if the government would settle over independence, the military, led by generals Massu and Salan, formed the Committee of Public Safety. It was obvious that France was facing a coup. Through the RPF, de Gaulle brought pressure to bear and was appointed president-premier with dictatorial powers for six months. A new constitution was drafted, giving the president far greater authority.

In October 1958, the Fifth Republic began with a Gaullist Party victory and de Gaulle appointed president for seven years. His period in office until 1969 was essentially one-party rule. The Algerian crisis gave him the opportunity to create riot police and employ secret-service methods that caused widespread condemnation. He also created a new relationship with France’s remaining colonies in the French Community. This enabled France to retain close economic links with her former African colonies.

Men of the Foreign Legion’s 13th Demi-Brigade in Algeria in the late 1950s.

In 1954, France was humiliated by its defeat at Dien Bien Phu. Its conventional forces had been defeated by a communist revolutionary war waged by peasant guerrillas backed by Communist China. While the French had striven to defeat the Viet Minh on the battlefield, they had done little to counter their grass-roots ideology. French promises to maintain the French Union, comprising mutually aligned territories, had a hollow appeal to those wanting full independence.

One of the greatest advantages that Giap enjoyed was that, although his men were trained and organized as regulars, with regiments and divisions, they also fought as guerrillas. This meant that they had firm command and control plus the discipline of regular solders, rather than being ill-disciplined militia. This discipline was enforced by the iron hand of communist ideology, which insisted on the greater good outweighing the needs of the individual.

In contrast, the French, despite their best efforts with airborne and mobile groups and local militias, never really mastered irregular or counter-insurgency warfare. Thanks to the Second World War and the Cold War, their ethos and doctrine were very much anchored in conventional warfare that was based on fighting set-piece battles. This was what they would have to do if called on to resist the armies of the Warsaw Pact. Ultimately, their lack of adequate off-road mobility and logistical back-up was their undoing in Indochina. It was not until the intervention of the American military, with the concept of air-mobile cavalry using large numbers of helicopters, that the conflict in Vietnam became truly fluid. French adherence to fixed defences at the end of their inadequate logistical lines was never going to be a war-winning formula.

France’s persistence in holding ground in Indochina drained its manpower and deprived it of the initiative. Even French mobile units had to rely on vehicles, not aircraft or helicopters, for quick reaction, which had left them constantly vulnerable to ambush. Defeat at Dien Bien Phu destroyed the French Union and the French Empire. Just as importantly, it showed the communist world what was possible. It ensured that, although the Cold War never became hot in Europe, conflict proliferated elsewhere in the world. In France’s case it led to the wholly unnecessary war in Algeria and yet more loss of life. Such was the tragedy of Dien Bien Phu. Vietnam, meanwhile, was consigned to yet another war.