7  FOR A SCIENCE OF THE INVISIBLE

FOR A SCIENCE OF THE INVISIBLE

Have you ever wondered why an entity is always as it is without losing its identity? Why does iron remain as iron and not change into copper or lead or wood, and why does gasoline remain so rather than turn to liquid nitrogen? Nature jealously guards the identity of any substance, and it remains itself for all time. So do the forms of a body’s architecture: stones, crystals, objects, plants, and animals. With difficulty we would observe a pencil case transforming itself—let’s say—into a glass, or into a bottle, or into something unknown. You wouldn’t even see it melting like snow in the sun, for example, slowly losing its shape, becoming mass without specific identity.

It is an extraordinary thing that bodies retain identity and form, since they are made of parts (atoms and molecules) that could be uncombined and then recombined to form different shapes. Why doesn’t it happen? If their matter comes from a common nursery of particles, why does an apple differ from a crystal? Who ordered them like that? What molds the shapes? If they were vibrating strings, who would play them? How is the rhythm established? How is it kept?

A minimum scrap of charges distinguishes the bricks of the universe; only the gradual addition of electrons causes their differentiation. We would only have to add an electron and a proton to potassium to transform it into calcium. But this does not happen. It can, but only in certain rare conditions. A camellia will bloom, make flowers, and die, but it will stay the same. An acorn will become a bud and then an oak: it evolves without losing identity. It will never happen that a rose will become an oak or will transform into a block of pyrite or a kangaroo. Why? What keeps the matter in the confines of the shape? What allows the bodies to preserve themselves? There must be something that gives them their border, a mechanism of regulation.

This is also true for cells: some system monitors and controls cellular homeostasis, and it checks the biochemistry. Have you any idea just how complex the network of chemical reactions within a cell is? It is far more complex than that of a computer circuit. Is it possible that this complexity is lacking a director? Who could be the director? Not the DNA. Despite their complexity, nucleic acids can’t have this function. There must be something to guide them, some kind of regulation circuits for every cell, for the organs, the systems, and indeed the whole body.

Fritz Albert Popp wrote that the models based solely on receptors couldn’t solve the fundamental problems of regulation because “every regulator needs in turn a new regulator and so on, infinitely.”1 There needs to be something at the top of the pyramid acting as the director: the ultimate regulator, intrinsic to the system (not transcendent), which could even identify itself in the system, in its entirety and complexity. This is what makes a system of self-regulation plausible, an SIR (system of intrinsic regulation) for each body, cellular or otherwise, expressing the basic code related to the body over which it has control.

In order to understand the concept of a system of intrinsic regulation, let’s proceed step-by-step, starting again from the elements. Imagine having an atom in your hand and looking at it attentively: its characteristics are given by the numbers of electrons and the distances of their orbits, which and how many particles form the nucleus, and so on. The balance of the electrons is essential, for if they were too close they would collapse on the nucleus, while being even a little bit too far away would cause them to shoot out into space; in both cases the atom would break up. The balance between the charges is only the mechanism, not the design. We have to discover what establishes the right distances between electrons. Matter is organized with mathematical precision, more the expression of a design than causality. Considering chance in this scenario is crazy: it would be like believing that—to cite a well-known Latin author—if millions of letters of the alphabet written on scraps of paper were launched into the air, they would fall back on the floor, assembled in such a way as to rewrite the entire Annales by Ennio.

Here we enter the domain of the maps of things. Chemical formulas are not enough to account for the anatomy and the physiology of bodies without the intervention of ordering principles and control mechanisms that are not molecular. For every entity there is a design template, a basic code, and a guideline for forming and maintaining the structure. The chemistry describes how and of what things are made, not how the ingredients are chosen, how they are mixed, in what measure and within what limits. There is still no answer to the ancient enigma of form and substance. We still do not know enough about what bodies are made of, about what exact criteria inform the choice of elements, and about how they are to be positioned.

We have seen that any construction is preceded by a design. Mother Nature does this with the codes, starting with pure matter, which is not yet determined and is therefore the mother of all things. Pure matter is the “immaculate conception.” What Virgin Mary represents is the Matrix that has not yet been “contaminated” by becoming this or that. In addition to Virgin Mary, the Matrix is the Great Mother in every era and culture: Ishtar, Isis, Astarte, Cybele, Demeter, Ceres, Brigit, and all others. So the first question is how a single form arises from the Matrix. The second is what mechanisms allow the bodies to retain form and identity. Let’s now find some answers.

We have seen that a thing emits information into its field. Our work with TFF, in which we have recorded and transmitted that information, has affirmed its presence in the field of each thing. That information is a necessary aspect of its own formation, that which “in-forms” it. It is that which acts as an architectonical schema from which the body derives its own structural references. There are some other functions. One is the homeostasis that guards and preserves what has been built. Once the construction of a house is finished, the schema ceases to be useful, whereas a natural entity requires its schema to be constantly present, otherwise it would disintegrate. If the electromagnetic component of the field is generated from the matter, it is also true that the matter is produced and maintained by the informational component of the field, by the continuous homeostatic process between fields and masses that inform one another. “It is the energy fields that generate the matter and not the opposite. They proceed and organize the formation of the physical body,” writes American colleague Richard Gerber.2

How do we imagine the basic codes? Seeing that in the universe everything vibrates, we can think about them as oscillations or rhythmical pulsations specific to a particular substance: hydrogen pulsates at a rhythm, oxygen at another, water at yet another, and so on. From these pulsating rhythms, changes in the basic rhythm of matter, foamy waves emerge from a peaceful sea. The physical bodies are nothing but expressions of frequencies, numerical sequences arising from the alternation of impulses and pauses. Intermittent signals, waves, and frequencies guide the architecture of the bodies in the direction foreseen by the basic codes to achieve a balance of charges and forms; matter is formed by the continued flux of information, the music of creation. It is through the music of the planetary spheres, such as the electronic clouds, that Mother Nature carves matter, making it perceivable. We are back to Orpheus.

The code generates the combined matter and then preserves its identity and form. The information acts as a unified force field, constant in its rhythms of pulsation, and as long as these rhythms are not altered, the matter remains itself and returns that information to the field in a process of continued self-regulation and indeed self-expression. Think about carbon, imagine it as dioxide embedded in a sugar molecule or in the paper of this page or in the fossil imprint in a rock. In any case, its code sends information to the molecules to place themselves in such a fashion as to constitute carbon: the number of atoms, protons, neutrons, and electrons it must possess, how they should be organized in the nucleus, at what distances they should orbit, how to rotate, with what spin. It communicates all of the chemical and physical characteristics that make sure that the substance is carbon and nothing else. The physical structure of the carbon is maintained by the signals that its code exchanges with the matter: the information travels from the code to the mass and back to the code again, like self-reflecting mirrors. Without basic codes, any body would disintegrate because it would lack its own references.

It is a wonder that table salt does not separate, disintegrate, or transform. It is all because of that program that governs from deep inside its atoms, in a space apparently empty, but instead one that is in truth the breeding ground of everything. Sodium chloride does not spontaneously disappear into sodium or chloride since the code of sodium chloride takes precedence over others. The salt remains salt, with all its properties. If instead, as Giordano Bruno wrote, we could modify the code, we could mutate a thing into another, as seemed possible for the ancient alchemists. They did it with metals. These are not fairy tales, but relate to recent events, from the last century.

Back to Marconi

I met Pier Luigi Ighina. I am the last man on Earth who interviewed him, a month before he died in early 2004; he was 94. For more than a decade he had worked with Guglielmo Marconi as a technician and his apprentice. He was not just a mine of knowledge and an author of brilliant discoveries, he was above all a great humble master of science and life.

At the age of sixteen he discovered what he called magnetic atoms. He could see them thanks to the atomic microscope he invented, which magnifies by 1.2 billion times. Based on his observations of atoms with his atomic microscope, he defined four fundamental laws pertaining to all atoms:

- When light atoms excite the observed atoms, the observed atoms absorb some of their motion.

- The observed atoms absorb part of the motion of the light atoms to speed up theirs.

- In order to excite an atom, it needs to be in contact with an atom of higher motion; the atom with the highest motion will attract the one with the lowest motion.

- The higher the atom’s motion, the more luminous it will be, and vice versa.3

Ighina classified matter according to the different pulsations and absorption rates of the atoms. Although he found that magnetic atoms are in all matter, he described them as having special properties not shared by all atoms. A magnetic atom is smaller and faster; in fact it is in perpetual motion. Its pulsation transfers movement to other atoms. In order to isolate it he created a kind of “wall” composed of different layers of atoms, setting the ones with maximum absorption (95 percent) at the inside close to the observed atom, and then one after the other, different types of atoms with diminishing absorption rates (85 percent, then 75 percent, and so on until 1 percent).

With this idea he was able to create “canals” that would take the motion away from the observed atom until it was almost still. They show up in the photograph he took of a magnetic atom in his laboratory in 1940 (fig. 7.1). The observed atom radiates pulsating magnetic energy into the surrounding space, visible—in the picture—as a thin luminous circle around the central atom.

Figure 7.1. The magnetic atom (from P. L. Ighina)

Putting a magnetic atom in contact with other different atoms, Ighina observed the following: when the magnetic atom is isolated it develops its maximum motion until it meets another atom of its same motion sensitivity (pulsation); the contacted atom starts to move and absorb pulsations from the magnetic atom until it has reached its maximum motion; at this point the two atoms split apart.4 But, since its pulsation is everlasting, it quickly recovers, and the whole process begins again. In this way he discovered that the magnetic atom is the one that gives motion to all the others.

According to Ighina, the shapes of different entities derive from the alterations of the vibrations of their atoms. He thought that the influence of the magnetic atom on the vibrations of other atoms indicated that it was responsible for all the variations of all atoms. So he developed an apparatus that enabled him to regulate the magnetic atomic vibrations. Through various experiments with it he discovered that he could change one formation of matter to another. Here is the description in his own words:

One day, once the regulating apparatus was tuned in to the vibration of a given matter, I left it in the same position until the next day. In the meantime the apparatus had changed its own vibration and that of the matter was in turn increased. I noticed that this matter seemed now to have a different structure, more similar to that corresponding to the new vibration. Other tests made me understand that by varying the vibration of one kind of matter it could be transformed into another.

With the same apparatus, one day I discovered the exact vibration of the atoms of an apple tree, and of a peach tree. I synchronized the apparatus with the vibration of the peach tree, then started to increase the vibration little by little until it reached that of the apple tree. The increase took eight hours, after which I kept the vibration of the peach tree at the vibration of the apple tree for sixteen days. Little by little I saw the peach tree transform and become an apple tree. With the same system, a Mayflower peach, which is a small variety, could be transformed into a larger variety of peach.

I started to do experiments with the same system on animals and I thus managed to transform the tail of a mouse into that of a cat. The duration of the transformation of the tail lasted four days, then it went back to the original state but it detached itself and the mouse died. The atoms of the tail didn’t take the alteration for long.

Even more interesting was the development of a bone of rabbit affected by osteomyelitis. The two ends of healthy bone near to the infected area had different vibrations. I tuned in through the apparatus with the vibrations of the healthy ends of the bone and I started to alternate to the maximum vibration, and I obtained the phenomenon of the reproduction of the atom. Soon, the two ends of the healthy bone came close until they met; this was accomplished by providing the continuity of the vibrations that had been interrupted by the infection. The bone went back to normal, as well as the vibration, and the fever disappeared.5

In the last interview of his life, Ighina was fully convinced that matter was rhythm that pulsates in different ways (a thought that is not so different from the superstrings theories). To transform a peach tree into an apple tree it is sufficient to record the rhythm (the basic code) of the apple tree and irradiate a peach tree with those frequencies. By knowing the code of things and working with it, it seems possible to change matter.

How did Ighina record the code of a tree? Here’s what he said in the interview: “Take an aluminum pipe, twist it to get seven spirals that you wrap around the tree branch and with an electric cable take it inside the laboratory.” Once he got the frequency, he could reproduce it so that another plant species could listen to it until it transformed itself into the initially sampled species. In other words, Ighina recorded the rhythm of the apple tree by capturing it from the field of the tree, confirming that the information radiates in the surrounding space. He was performing a TFF from plant to plant. His experiments also confirm that by possessing the code of a substance, we can do what we want with it. Here physics is combined with magic and alchemy, which perhaps are three different aspects of a single thing.

As far as alchemical transformations are concerned, other testimonies come from the French doctor C. Louis Kervran, a member of the Academy of the Sciences of New York, who in the late 1950s had documented a case of spontaneous transformation of elements. As mentioned before, adding a simple electron to potassium will transform it into calcium; this transformation naturally takes place in some living things. Chickens subjected to a diet completely devoid of calcium produce eggs without shells, while a diet without calcium but rich in potassium immediately brings the shells back. The alchemy of the organism transforms the potassium into calcium.6 The SIR of the chickens knows that there is an absolute need for calcium and tells the potassium to transform itself into calcium.

But let’s go back to Ighina, who photographed that particular atom that sets the rhythm as a pacemaker. Its pulsation transfers its characteristics. What he calls the magnetic atom could be an expression of the basic code that informs the field (“it pulsates and radiates energy in the surrounding space”), whose vibration the atoms record so they can express substance and quality together. It builds the shape. When Ighina observed the perturbation of space, he expressed it in a way sounding like the basic code: “I noticed that each type of matter has its own magnetic field composed of magnetic atoms and atoms of the matter itself.”7

The basic code would be the inexhaustible source of the information that organizes matter, powerful enough that, transmitted to a second substance, it takes the characteristics of the first. In the TFF, information is transmitted just like in the experiments of the follower of Marconi, such as transferring to a mouse the information of a cat, so that the code of the mouse is modified into that of the cat—“biological TFF”! When a code is transferred, matter is transformed.

The same happens with abrupt alterations of magnetic fields and electrostatic variables recorded near volcanoes in geologically active areas, especially before earthquakes. Earthquakes are preceded by intense fluctuations of the geomagnetic field, orthogonal microwaves near the terrestrial surface that, according to Giovanna De Liso, can be seen as indicators of their occurrence. She has experimentally investigated variations in the electric conductibility of rocks and their magnetic permeability, which form between them an electrostatic field, like in a condenser, in connection with the so-called Shroud effect. The Shroud effect refers to whether images of objects lying between the two folds of a linen cloth of characteristics similar to those of the Turin Shroud, smeared with different solutions (aloe, myrrh, blood in a water/ oil solution) and placed between two horizontal gneiss rock layers in an underground cellar partly excavated in ferromagnetic rocks, could form naturally before or during an earthquake. Among the leading experts on the historic cloth kept in Turin, whose image seems to refer to Jesus, De Liso managed to imprint images of different objects by using the technique just described (may we remind you that the Gospels and pagan literature speak of intense earthquakes at the moment of Jesus’ death on the cross and in the following days).8

This is almost a geological TFF. In our transfers, the information is transmitted in a similar way, with variations of electrostatic fields, just like in a radio. And so we are back to Marconi. TFF, radio, and the Shroud effect all seem to testify that, through field variations, nature can transfer information from one system to another. These transfers can also be translated into sounds and images.

Communication between Things

Something similar to the “transformations” made by Ighina was realized by the Chinese scientist Chang Kanzhen, together with Gregory Kazmin, director of the Institute of Research for Agriculture in the Far East. Kanzhen built a transmitter of biomicrowaves that transferred information from one living being to another, plant or animal. By irradiating seeds of corn with informed waves from wheat, the corn plant produced grain similar to both wheat and corn. From chicken eggs irradiated with the information of a duck came hybrid chicks.9 It seems that a growing organism manifests aspects of the form corresponding to the irradiated information. The experiences of Ighina and Kanzhen support the hypothesis of the basic code, responsible for the forms transmitted to other bodies, almost a TFF in a cellular environment.

The informational essence of the basic codes is communicated by sequences of impulses and pauses that mark the vibrations of the bodies, which teach the matter in which rhythms to oscillate. Different things exist because they vibrate at different frequencies. The codes set the rhythms by which things are differentiated. The space surrounding the body is never still, and the information in the field is the same that vibrates within the body. It is able to interfere with the environment to inform it. The information is spread from a body in an incessant and continued way, without ever being exhausted or consumed, as long as its basic code exists.

Thus bodies are more extended than how we usually perceive them: they have an invisible part made up by the informed field arising from the basic code. They are pulsating dynamic structure—motu proprio—which the senses don’t perceive. The information that organizes molecules propagates through the perturbation of the field to the structures of the body in order to communicate with the environment. It is the emanation we record from the medicines and that Ighina captured from the branches of the tree. This is how bodies “communicate.” Let’s try to find out how.

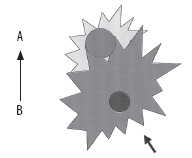

Theoretically, the informed fields of two entities can interact in a simple way or in a transgressing way. In a simple interaction between two bodies in contact, information about each one’s identity is exchanged through their fields, and both substances gain experience of each other (fig. 7.2).

Figure 7.2. The simple interaction model between the informed fields of the bodies A and B. The exchange of information is reciprocal, and each field continues to be informed of the other for a time.

Two people meet—“Good morning, I am Tom. Nice to meet you, I am Dick”—and they define themselves by sharing their codes. An object relates to another about its qualities (shape, matter, color, consistency, structure, property, and so on), and vice versa in the same way. Through the basic codes, bodies are always informed of what happens in their surroundings.

In water, the field variations are better fixed and last longer. Schimmel’s experiment, mentioned earlier (in chapter 5) demonstrates a simple interaction in which the homeopathic phial transmits information to the water in which it is immersed and the water becomes a copy of it. Water could also transmit its code to the phial, except that water acts as a universal receiver: it can receive imprints of everything without giving anything of itself. Also, even if there were a transfer of water to the remedy, it wouldn’t be possible to verify it.

Let’s look at another situation. Again, let’s consider two people introducing themselves: one shouts his name in the other’s ear, and she is stunned and overwhelmed. It is not an exchange anymore, but a monologue, a one-way communication. It is a transgressing interaction when the field of a substance is powerful enough to make the emission of its signals more intense; once they become sufficiently penetrating, they transgress the field of the other substance (fig. 7.3).

The transgressed field changes its rhythm and enters into a new matter state by becoming similar to the other substance. The level of resemblance depends on the information and the conditions of transfer. The stronger one transmits to the other until they oscillate together. The TFF we have performed on liquids is a transgressing interaction because the generator activates the information from the medicine, which makes the water vibrate to its frequency; in this way the medicine is copied into the liquid. Similarly, in the preparation of a homeopathic remedy, the succussion that transmits the oscillation of the solute to the water molecules creates a transgressive interaction.

Figure 7.3. Transgressing interaction model. The activated field of substance B strongly imprints itself on the field of substance A.

The same interactions—both simple and transgressing—that govern exchanges between things are found between things and organisms. Simple interactions are demonstrated by medicine tests (such as kinesiology, electro-acupuncture, or auricular medicine) in which the organism “feels” the field of the medicine by reacting immediately. Communication goes the other way as well: a person can inform an object. If an object belonged to Tom before being used by Harry, the field of the object will retain morphological and emotional information from Tom as well as Harry. Those who are very sensitive or psychic and come into contact with an object are able to read life events or emotions of the people whose field has become imprinted in the object. This is termed psychometry. This is not parapsychology, but the physics of interacting fields. If the transfer is transgressing, memories of particularly intense emotions or of other dramatic facts can imprint into an object for centuries.

A Theory of Communication

“Our universe it is not all that makes up the cosmos. The greater reality is the Mother of our universe and maybe a large number of others, some prior to ours, others coherent with it,” writes Laszlo.10 He is convinced that even the communication between universes is made via an incalculable amount of information, perhaps through black holes, where spatial-temporal laws are not respected anymore.

Let us remain in our universe, where information is exchanged through signals. In the light of what we said before, the exchanges should take place in two ways: molecular action and field interaction. In the first, molecules with “strong interactions” at a short range transmit the messages. These are the chemical reactions that form stable ties with the vicinity. The kinetics of field interactions, whether simple or transgressing, are long-range “weak interactions”; they are able to act at a distance without forming chemical bonds. Two substances react chemically in close proximity; it is also possible for the weak signals of the molecules to produce effects across longer distances, with field actions. For example, we have seen that a medicine can be administered in both ways: in molecular kinetics, the cell receptors are stimulated according to the model of “key in the lock,” where the drug acts on the receptor molecule as a key, which is able to open it; in the field of kinetics, however, the receptors are activated by the signals of the medicine, like a remote control of the lock.

The action of the field is masked by that of the molecules, and in some cases occurs beforehand, from the first contact of a medicine with the patient taking it (because the signals don’t meet any obstacles and they can’t be modified). Lehninger*25 observed that identical biochemical reactions are faster in vivo than in vitro. This may be due to the fact that, in the organism, the weak action of the field is amplified in relation to the number of cells, becoming faster and more efficient in complex systems. This is what we have observed in the effects of TFF on multicellular organisms compared with unicellular. This is in accordance with the Kaiserslautern postulate, which states that the more complex the system, the more complete the decoding of the signals. According to complexity theory, a system designed as an aggregate of parts interacting with each other can have different behaviors than the individual parts themselves. In other words, an organism may react differently from some of its cells within the whole.

Because of the kinetics of fields, a drug can act even in the absence of molecules. The opposite, namely action arising from a molecule disconnected from a field, is not possible, however; having lost its own structural references, the matter would break up. While there may be fields devoid of molecules, it is not possible to have a body devoid of a field.

Psychometrics suggests that bodies can “memorize” structural and emotional information from beings that they come into contact with. This topic will be dealt with further on in the chapter on emotional fields (chapter 11); for now we will talk about the contact itself. The word contact is derived from con, “together with,” and tangere, “to touch.” When two human hands touch, not only are the touch receptors stimulated, but there is also a meeting between fields. The two phenomena overlap, making it difficult to notice the field interaction. When a hug or a handshake is exchanged, the essence of each person—his or her entire code—is communicated to the other, making it possible for them to read inside each other. But only someone who is sensitive to field changes can use that awareness to perceive illness or the particular moods of others. The aforementioned words of Jesus, who knew that virtue had gone out of him when his robe was touched, can be interpreted as a reference to the contact between fields.

The physiology of the senses should be reviewed in light of the physics of the informed fields. For example, the sense of smell seems stimulated by volatile molecules, but this does not explain some sensory situations. How do you explain that a sniffer dog can find minuscule quantities of a drug wrapped in many layers of clothes inside a case, only on the basis of the molecular model? Even admitting that some molecules might spontaneously detach themselves from the drug, how could they escape the plastic bag, go through layers of clothes, and pass through—God only knows how—the side of the case to fly freely in the air and hit the receptors of the mucous membrane of the dog? It is against the principle of physics. It is like a tunnel effect, a quantum phenomenon where a particle is able to go through an energy barrier even if its energy is less than is needed to do so from the classical physics point of view. What energy could make the molecules overcome so many barriers? Generated from what?

It seems far more plausible that the field of the drug became resonant with the layers of clothes, the leather of the case, the air, and the sensory receptors or the field of the dog itself. Where a molecule is unable to go, a signal can penetrate. As we have seen, the signals of medicines pass through glass. Those of dopamine reach even the midbrain of the Parkinson’s sufferer, whereas dopamine molecules are blocked by the blood-brain barrier. If the senses are stimulated not only by molecules but also by signals from fields, a dog trained to a particular resonance of a particular drug possesses receptors able to resonate with the basic code of that substance.

Thanks to the long-range field reactions, similar molecules can feel at great distances and vibrate at the same frequencies, even if other molecules are between them. Oscillating the molecules at the same frequency for the duration of the biochemical reaction is like dialing a number with a phone and maintaining that connection for the duration of the call. Nothing can distract those two that are calling each other. The theory of superradiance, describing the effects generated by particles of coherent matter oscillating with their electromagnetic fields, states that a messenger molecule introduced into a cell goes directly toward the target, as in a transmitter-receiver connection. On the other hand, traditional biochemistry suggests that, before reaching the target, molecules would sustain incalculable and unnecessary collisions with others. The traditional model expresses mechanistic thinking, which is complicated beyond belief. Nature does not waste time and energy in attempts if it can achieve safe results immediately and with minimum effort.

Psychometrics and the compatibility tests of medicines confirm exchanges with contact or minimum proximity. Long-range interactions can be seen in processes like dowsing, in which messages from underground are received; this takes place through resonance with the fields of water, oil, or other mineral layers. The literature on the phenomenon of nonlocality documents occurrences of simultaneous influence in spatial conditions that would make any communication impossible. They are explained by admitting the existence of a background continuous connection of their fields.

At this point, we must take another break to observe the images that, as in the kaleidoscopes of our childhood, can be imprinted on water and on matter in general: the embellishments, arabesques, and even crystals that music can imprint into things. We return to talk about water and what it has to do with lights and sounds.