Making an Ethnography of Networked Social Media Speak to Challenges of the Posthuman

For approximately ten years I was a participant-observer of Cyborganic, a group of San Francisco web geeks who combined online and face-to-face interaction in a conscious project to build community “on both sides of the screen.” Cyborganic members brought Wired magazine online; launched Hotwired, the first ad-supported online magazine; set up web production for CNET.com; led the Apache open-source software project; and staffed and started dozens of Internet enterprises, such as Craig’s List, during the first decade of the web’s development as a popular platform (1993–2003). Cyborganic pioneered self-publishing and featured some of the earliest online diaries before these were called “blogs,” most notably Links from the Underground by Justin Hall, a “founding father of personal blogging” (Rosen 2004), and Brainstorms by author Howard Rheingold. The new imaginaries and practices of networked, social media that Cyborganics integrated in their daily lives during this period are recognizable today in Facebook,1 Twitter,2 and a variety of other forms of many-to-many online media centered on self-publishing, user-generated content, and social networks.

DOI: 10.5876/9781607321705.c01

Throughout this work, I use the terms online and onground to talk about ways networked media were integrated in the whole of my Cyborganic informants’ lives. Online is the conventional term for computer-mediated communication, and I came up with onground because I needed a convenient way to refer to aspects of Cyborganic that were not, or not only, online (e.g., working and living together, interacting face-to-face). Instead of offline I decided onground was more descriptive of these place-based aspects of Cyborganic. However, it is vital to make clear that the distinction between onground and online is not that the former is material and the latter immaterial. However tempting and common sense that assumption, online communications clearly have material bases in physical hardware (machines and wires) and material forces of production and consumption.

The work of geographer Edward Soja is particularly valuable to thinking about how computer-mediated sociality challenges the assumptions of place-based ethnography. Soja argues that, just as the physical world can be divided in to space, time, and matter, the abstract dimensions of spatiality, temporality, and social being “together comprise all facets of human existence” (Soja 1989, 25). He calls this triad the “ontological3 nexus of space-time-being.” These basic dimensions of human existence are not natural or given but rather social constructions that shape empirical reality and are simultaneously shaped by it (Soja 1989, 25). That is, the relation between the physical triad (space, time, matter) and existential triad (spatiality, temporality, and social being) is already mediated through language and socialization. Computer-mediated communication blurs and shifts relations of spatiality, temporality, and social being—Soja’s basic facets of human existence—and thus calls into question traditional conceptions of the anthropological subject. Although the tremendous growth of real-time, global, information networks untethers social being from many of the spatial and temporal constraints to which it had been tied, it does not dematerialize these facets of human existence. Soja’s theory helps conceptualize these relationships and informs the concept of colocation developed in my analysis of Cyborganic in Part 1. It also informs my approach to questions of virtuality, materiality, and embodiment that have long attended the study of life online (Turkle 1984, 1995; Stone 1991, 1995; Dibbell 1998) and figure centrally in competing visions of the posthuman presented in Part 2.

Started in an apartment in a two-story Victorian in San Francisco’s Mission/SOMA (South of Market) district, Cyborganic was a neighborhood cooperative, social clique, artist organization, professional network, and Internet start-up business. The Cyborganic business concept can be traced back to 1990, and the community can be traced to the San Francisco rave scene of the early 1990s and the SFRaves mailing list started in 1992. Described by Rolling Stone magazine as “a community of webheads who live in and around an apartment on Ramona Street on the outskirts of ... Multimedia Gulch” (Goodell 1995) and by Wired News as “an influential early Web community” (Boutin 2002), Cyborganic’s central project was to create a “home on both sides of the screen” (Cyborganic Gardens website, 1995).

Onground as a local, face-to-face community, Cyborganic comprised three concentric, overlapping entities. First, there were several group households on a single block of Ramona Avenue, known as “The Ramona Empire,” which had a peak of approximately twenty residents during the years 1995–1999. Second, there was the Ramona LAN (local area network), a physical network of computers, wires, and buildings whose maximum reach was across eleven separate rental apartments, providing approximately thirty-five people with full-time residential connections to the Internet for more than a decade. The third and largest of Cyborganic’s face-to-face venues were weekly community potluck dinners, known as Thursday Night Dinner, or TND. With approximately 100 regular attendees from August 1995 through the end of 1996, TND was, as Wired News put it, “the place to be for San Francisco’s up-and-coming Web workers” during the dot-com boom of the 1990s (Boutin 2002). These three place-based parts of Cyborganic—the Ramona Empire, local area network, and Thursday Night Dinners—are diagrammed above in Figure 1.1.

Cyborganic as a place-based, face-to-face community. Peaks reflect the largest number of simultaneous members in each group. Totals are the number of members over the life of the group.

Online, Cyborganic included the following forums, illustrated in Figure 1.2. Cyborganic’s web and mail servers hosted approximately 100 user accounts and more than 100 virtual domains between 1994 and 2002. The cc list, a community e-mail list, was the most central of Cyborganic’s online forums. Launched in 1994 with 33 subscribers, it grew to 152 subscribers by mid-1996, had a peak of more than 200 in 1997, and remained active through 2002. Cyborganic also had a website, Cyborganic Gardens, which showcased the community and business and hosted member homepages and projects. Cyborganic had thirty-four member homepages when the website went online in April 1995 and eighty-six from January 1996 through the winter of 1997 when it went offline. Finally, Cyborganic’s online venues included the space bar, a text-based synchronous conferencing system, or “chat,” that was active from April 1995 until mid-2008.

Cyborganic online.

In the large-scale view, my ethnography situates Cyborganic genealogically in relation to two cultural histories: first, of Silicon Valley as a region of technological and economic innovation; and second, of Bay Area counter-cultures and the role these played in the social construction of networked personal computing. Both highlight the formative role of place—physical colocation in particular places and the embodied, face-to-face sociality that this affords—in the development of networked media.

From the “community of technical scholars” envisioned in 1927 by Fredrick Terman, the Stanford professor who played a key role in the creation of Silicon Valley, to the “faires,” hobbyist clubs, and local businesses that ushered in personal computing in the 1970s (Freiberger and Swaine 2000), spatial proximity and face-to-face sociality have been central to the development of information technologies. Scholars of urban development (Saxenian 1993, 1994; Castells and Hall 1994) and economic history (Kenney 2000) identify Silicon Valley as an example of the “technopole” and emphasize the crucial role of place and culture in technical innovation and “dynamic economic growth” (Castells and Hall 1994, 8). More recent studies have demonstrated the extraordinary spatial concentration of the Internet industry and the continued importance of geography in the network age (Zook 2005; Saxenian 2006). During the 1990s the SOMA district in San Francisco, where Cyborganic formed, emerged as “a new Silicon Valley,” about forty miles to the north, in a process of “short-distance decentralization” (Castells and Hall 1994, 235) in which technopoles spawn nearby satellites. My ethnography of Cyborganic demonstrates how spatial proximity and face-to-face sociality worked together in SOMA in the 1990s to “foster dynamically evolving networks of relationships” among emerging businesses and outposts of larger enterprises, in “a kind of fishnet organization” (IFTF 1997, 2).

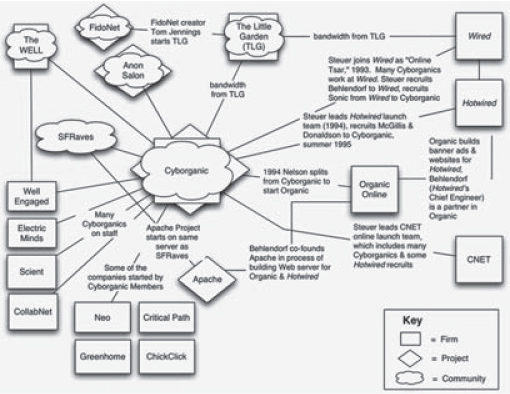

The significance of place and embodiment can be seen, for example, in the fact that Cyborganic was an age cohort (a group of people of the same generation) that came together through a variety of kin, high school, college, and occupational networks. Figure 1.3 diagrams the network of firms, projects, and professional and recreational communities in which Cyborganic formed, tracing its connections to the new businesses and software projects through which web publishing developed in San Francisco in the 1990s. Although a few lines of connection in Figure 1.3 represent Internet connectivity as well, all lines represent flows of people, ideas, and collaborative action. In this diagram, the multiple, overlapping, graphic shapes (cloud, diamond, rectangle) illustrate the overlap and interconnection of social forms—businesses, voluntary projects, and communities of work and leisure—and, thus, of work and play, professional and personal. The concentration of Internet firms, projects, and communities in San Francisco’s tiny SOMA district (less than one square mile) illustrates the interdependence of onground and online sociality. These were the small-scale social forms and boundaries my Cyborganic subjects negotiated as producers and consumers of new forms of networked media during the first phase of the web’s development as a popular platform during the 1990s.

The other relevant regional legacy for Cyborganic is that of the Bay Area as a center of 1960s and 1970s American countercultures. The vital role of these countercultures in the emergence of networked personal computing and virtual community has been well documented in a variety of contexts (Roszak 1986a, 1986b; Brand 1995; Abbate 1999; Castells 2001; Roy 2001; Markhoff 2005; Turner 2005, 2007). Communications scholar Fred Turner (2005, 2007) traces the role of Bay Area countercultures in the emergence of online communities through the WELL (Figure 1.3, top left), an online community and business founded in 1985 by Stewart Brand and Larry Brilliant. WELL stands for Whole Earth ’Lectronic Link and is a reference to Brand’s earlier enterprise, The Whole Earth Catalog, a handbook of the hippie generation. Profiled in Rheingold’s The Virtual Community (1993), the WELL is one of the oldest online communities and also one of the most studied (Smith 1992; Figallo 1993; Hafner 1997; Wellman and Gulia 1999; Kollock 1999). The WELL, Turner argues, “not only modeled the interactive possibilities of computer-mediated communication but also translated a countercultural vision of the proper relationship between technology and sociability into a resource for imagining and managing life in the network economy” (Turner 2005, 491). Cyborganic inherited from the WELL a small but formative membership and, more significantly, the entrepreneurial and utopian vision to start a locally based online community and make a business of it.4

Cyborganic network of firms, projects, and communities, San Francisco, 1993–1999.

Situating Cyborganic in this brief cultural history highlights the vital role local communities have played in the development of the Bay Area as a techno-pole and of networked personal computing and shows the continuing importance of such groups to web publishing in the 1990s. Cyborganic combined the identity and trust-building power of face-to-face forums with the flexibility and greater reach of computer-mediated communication. This combination resulted in a community colocated in places online and onground and in the hyper-experience that results when these two are deeply intertwined.

The large-scale view described so far illustrates the importance of place in the development of web publishing. Now I turn to the small-scale view to focus on specific imaginaries, practices, and forms of networked media in the daily life of Cyborganic. Ethnographic analysis of these forms and practices demonstrates the way online intermediation can reconfigure experiences and imaginaries of place, identity, and embodiment without dematerializing these sites of subjectivity or rendering them obsolete as sources of anthropological insight. To make this demonstration, I begin with a few definitions and concepts before turning to examine one specific part of Cyborganic (the space bar chat) for what it shows about the interdependence of online and onground social forms.

In the 1990s, anthropologists (Appadurai 1990, 1991; Gupta and Ferguson 1997a, 1997b, 1997c) challenged the assumed “isomorphism between space, place, and culture” (Gupta and Ferguson 1997a, 34) and theorized “technological infrastructures as sites for the production of locality” without a necessarily geographic referent (Ito 1999, 2). Despite this decoupling, or unlinking, of social location from physical space, my Cyborganic study illustrates how spatial proximity onground and technologically mediated presence online continue to interact in significant ways. Rather than arguing for a return to place-based ethnography of face-to-face communities (see, e.g., Foster 1953; Redfield 1960), my emphasis on place builds on a concept of colocation—the colocation of people, jobs, and social activities together in particular places and channels of communication—that applies equally online and onground. This understanding of colocation is informed by Lisa Gitelman’s definition of media “as socially realized structures of communication, where structures include both technological forms and their associated protocols, and where communication is a cultural practice, a ritualized colocation of different people on the same mental map, sharing or engaged with popular ontologies of representation” (Gitelman 2006, 7, emphasis added). Although media can be defined as “communication that is not face-to-face” (Spitulnik 2001, 143), the “ritualized colocation of different people on the same mental map” that Gitelman describes is a cultural practice that takes place onground as well as online. Moreover, it is one that figures centrally in Cyborganic’s imaginaries and practices of networked social media, where online and onground colocation worked synergistically to reconfigure the experience and social relations of presence and place. For example, a 1995 manifesto on the Cyborganic website proclaimed: “Cyborganic will establish a real space for members to meet and interact—a flesh-and-blood back-channel—to its community-building efforts in cyberspace” (Cyborganic Garden website, “Our Big Plan”). “Back-channel” implies all the informal communications and interactions around a main channel. In telecommunications a back-channel is usually a lower-speed transmission flowing in a direction opposite the main channel. The irony of imagining “real space” and “flesh and blood” as the back-channel to online interaction is that face-to-face interaction offers a far richer spectrum of communication. All kinds of subconscious and preconscious communications flow across in “full duplex”—that is, in both directions simultaneously. This example serves to highlight the mutuality of online and onground in that both forms of interaction and social space are imagined as channels.

This is a thoroughly “infomated” imaginary of location, to use Shoshana Zuboff’s (1988) term for the way information technologies support richer communication around the tasks to which they are applied. In 1988, Zuboff identified a “fundamental duality” between technologies that automate, that is, “replace the human body ... enabling the same processes to be performed with more continuity and control,” and technologies that, in her coinage, “infomate,” meaning they simultaneously generate “information about the underlying productive and administrative processes” of whatever they automate. Although the logic of automation “hardly differs from that of the nineteenth-century machine system,” Zuboff observes, “information technology supersedes the traditional logic” because it feeds back on itself by introducing “an additional dimension of reflexivity ... Information technology not only produces action but also produces a voice that symbolically renders events, objects, and processes so that they become visible, knowable, and shareable in a new way” (Zuboff 1988, 9–10).

Technologies that infomate form the technological nucleus for the array of contemporary phenomena known as “Web 2.0,” and their voices can already be heard in my Cyborganic research. Let me illustrate by looking at one aspect of Cyborganic—the space bar chat—where I identify practices of colocation, presence casting, phatic communion, and configurable sociality, all of which express the mutuality of online and onground in the daily life of Cyborganic.

Space bar was an online chat where multiple people logged into the same channel to exchange text messages in real time. Space bar was not on the web but had a text or command-line interface and was accessed using the older telnet protocol. From the time it went online in April 1995, space bar had a contingent of regulars who spent much of each workday logged into the chat. Most were people whose jobs entailed being online at a computer much of the day, as these interview excerpts illustrate.

I’m usually on the space bar by eleven thirty or eleven, say, and bail for lunch, go outside and talk to my tape-recorder or talk to my journal, or play guitar or something to get the stress out and then, show up at one and deal with afternoon meetings and then by, easily, definitely by three I’m back on “the bar.”

(DOMINIC SAGOLLA, INTERVIEW, OCTOBER 17, 1996)

It’s certainly busier during the day, during the week, when everybody’s supposed to be working and they’ve got their telnet window open, on their computer desk ... (laughs)

(KAT KOVACS, INTERVIEW, OCTOBER 8, 1996)

Being on space bar was integrated into the workday and workplace. For Cyborganics with day jobs in San Francisco’s SOMA neighborhood, space bar was a place to find people to go to lunch with during the week and talk about lunch afterward, back at work. For those who worked “down peninsula” in Silicon Valley, keeping a window open to space bar all day countered the isolation of the commute and corporate workplace, or “Cubeland,” as some of my informants called it. Having a cohort of knowledgeable friends with you on your desktop at work dramatically changed the character of the workplace for the Cyborganics who frequented space bar. More widely, such forms and practices of techno-sociality (e.g., instant messaging, texting) have been identified as central to the new workplace of a “creative class” (Florida 2002) of “no-collar” workers (Ross 2003) associated with the new economy and 1990s dot.com boom.

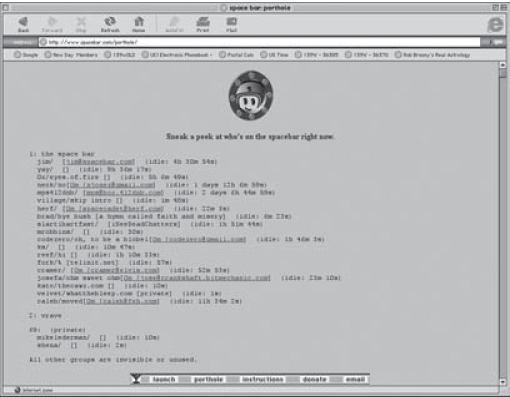

Besides hanging out, gossiping, and bantering in the chat, Cyborganics used space bar as a hailing frequency. Even those who did not generally spend much time in the chat logged in when they needed to track somebody down or talk to a “live person.” To facilitate this practice, Cyborganic’s web team created a “porthole” on the Web (Figure 1.4), a webpage people could visit to see who was online in the chat without having to telnet to space bar and log-in.

Cyborganic also devised a “cadet detector” (Figure 1.5) that members could put on their homepages to indicate automatically with a graphic icon if they were logged in to space bar.

In the context of the porthole and cadet detector, people began using the space bar’s nickname feature to append short status messages of different kinds (e.g., mood, location, role) to their log-ins. Displaying your presence across media—that is, from the space bar chat, which was not on the web, to a page on Cyborganic’s website or a member’s homepage—was what I call “presence casting.” As the status updates so central to more recent online media such as Facebook and Twitter illustrate, this form of mediated communication has proliferated with the rise of the mobile Internet and social networking.

Beyond its presence in the workday, the chat was also active late at night when regulars logged in from home or while working after hours. As one of my informants said of space bar in 1996, “people live there”; some even stayed logged on when they were asleep or otherwise out of range of the “beeps” that users could send to one another’s computers. When asked about this practice, some suggested it was “a status thing to be on the bar,” whereas others indicated that staying logged on gave a sense of “being together” that was comforting. In this, and other practices, space bar served an essentially phatic function of maintaining social connection rather than communicating messages. Here I draw on Bronislaw Malinowski who “coined the phrase ‘phatic communion’ to refer to [the] social function of language, which arises out of the basic human need to signal friendship—or, at least, lack of enmity” (Crystal 1987, 10; Malinowski 1989 [1923]). Linguist Roman Jakobson described the phatic function as one of contact over message where messages serve “primarily ... to establish, to prolong, or to discontinue communication, to check whether the channel works,” to attract or confirm attention (Jakobson 1981, 24). Space bar was online for thirteen years, and a group of about fourteen people continued to log-in through early 2008, mostly to idle together in the channel or engage in conversations that proceeded at a rate of one or two lines a day. Thus, in its last years of operation, space bar primarily provided phatic communion through a structure of communication that in its very minimalism demonstrates Gitelman’s point that media are never only technological but always include and are realized through social protocols and cultural practices.

The space bar porthole.

In technical terms, one might say this use of space bar automates the phatic function of communication in its display of users who are logged into the channel. But the function is also infomated with automated messages from the system (idle time), as well as customized messages from the users (e-mail addresses, nicknames). For example, one’s presence on space bar was displayed automatically (in the text chat and through the web porthole) in the following form:

The space bar cadet detector.

cool/anthropologist [jenny@cool.org] (idle:0s)

jim/obamageddon [jim@spacebar.com] (idle:23 days, 11h, 17m, 56s]

In this example, I (cool) have just logged in (idle:0s means idle for zero seconds), whereas space bar’s systems administrator, or sysadmin, (jim) has been logged on and idle for almost twenty-four days. Appended after each log-in are “nicknames” (anthropologist, obamageddon), as they are called in space bar’s command menu, although, as noted, they came to be used for status updates and short-form messages (in this example, political commentary), rather than to convey a fixed identity. Even in the rather limited use of its later years, space bar included a range of social functions and cultural meanings. Besides the phatic communion of a small group of old friends who stayed logged in to the channel, it provided a way for Cyborganics, many of whom had left the Bay Area by this time, to locate space bar regulars and learn when they had last said something in the chat.

The imaginaries and practices of colocation, presence casting, and phatic communion described in space bar reflect a form of just-in-time, configurable sociality that has proliferated with the media forms and practices collectively known as “Web 2.0,” for example, in Facebook status messages or micro-blogging on Twitter. Facebook also demonstrates the central importance of place in establishing high trust social networks that can be augmented and maintained at a distance and over time through networked social media. Although it is now a global social networking site, Facebook was initially restricted to Harvard college students. Created in late 2003, it was an online representation of students’ face-to-face community using real names and pictures from college identification cards (IDs). Within months, membership expanded to Stanford, Columbia, and Yale, then all Ivy League and Boston area schools, and later most North American universities. In September 2006, membership opened to anyone thirteen or older with a valid e-mail account. The connection of online and onground identity and extension of traditional place-based affiliations, such as college ties, are as central to Facebook as they were to Cyborganic and illustrate ways that although place-based identities and affiliations have been extended in time and space and reconfigured through networked sociality, they remain significant.

A central aspect of configurable sociality is the way it mediates online and onground presence, identity, and colocation. This can be seen in practices of using pseudonyms on space bar that tended to render identity configurable, obscuring or revealing onground connections depending on social context. Space bar constituted a liminal zone as a channel people could enter and use without revealing their onground identities. Anyone on the Internet could log-in and chat in space bar’s channel 1 until the administrator (“the spaceman”) verified a working e-mail address, at which point users could join any public channel and create public or private channels of their own. In addition, one person could have multiple accounts. As long-time systems administrator for space bar James Home notes, “A lot of the Cybo establishment used the same names [on space bar] as their main accounts but had aliases for fucking around” (James Home, personal communication, March 19, 2008).

About half of space bar’s users had a log-in different from their main Cyborganic account, and although some might know who was who “in real life” (IRL), others might not. In this context, it became fairly commonplace for space bar regulars to have fun by fooling or tricking “chat newbies,” as one regular described in a 1996 interview.

Tunaluna is a space bar regular and she is usually very helpful to everybody, although she also just has fun playing around with newbies in channel 1 under a different ID, and as the moderator she has another log-in which if you ask her, she’s always pretty helpful, but she also plays with newbies. There was one great evening, me and her and there were two other people and a couple newbies and within about half an hour we had them believe that everything they said was being measured for some big government project from Iowa and everything went into this big computer to design chat machines for the next generation. It’s really childish at some level, but it’s a harmless game that some people play, but then as the moderator log-in, she wouldn’t do that, she would not intentionally mislead people [laughs].

(SEAN ROBIN, PSEUDONYM, INTERVIEW, OCTOBER 21, 1996)

As this interview excerpt indicates, even space bar’s moderators had different aliases and engaged in the in-group games with neophytes. These are practices of pseudonymity rather than anonymity, because the regulars in the online chat know the onground identity of each other’s aliases, even though less frequent users would not. Aliases meditate online and onground by inserting a degree of distance (or freedom) between them, a configurable boundary some can see through and others cannot. This example demonstrates the way online practices express onground social relations, albeit in complexly reconfigured and reconfigurable forms. Each of the social imaginaries and practices described and analyzed in this chapter—colocation, presence casting, and configurable sociality—demonstrates ways in which the unlinking of social and physical proximity (of online from onground) opens new possibilities for their recombination and reconfiguration. None suggests the dematerialization of place or erasure of embodiment as a consequence of the proliferation of computer-mediated interaction. Rather, in the case of Cyborganic, mediated and face-to-face communication worked together synergistically to reconfigure the experience and social relations of presence and place.

My analysis of Cyborganic’s online and onground mutuality suggests ways to think about challenges to traditional conceptions of the anthropological subject that I refer to as challenges of the posthuman. Although I recognize the term posthuman is one anthropologists might find problematic (Boellstorff 2008, 28–29), and I even share some of their discomfort with the word, examining the figure of the posthuman proves valuable to understanding questions of virtuality, materiality, and embodiment that attend the reconfigured relations of space, time, and being in the cultural worlds of the computer-mediated sociality that I study. Engaging the posthuman brings these questions into a broader discourse about challenges to inherited conceptions of the human subject posed not only by the proliferation of technologically mediated sociality but also by a succession of postcolonial, feminist, and postmodern critiques since the 1980s (Hymes 1974; Said 1978, 1989; Fabian 1983; Clifford and Marcus 1986; Marcus and Fischer 1986; Geertz 1988; Clifford 1988). By speaking of these together as challenges of the posthuman, I argue that, although it is vital for anthropologists to recognize diverse ways in which the historically specific construction called human continues to give way to a different construction, which some call cyborg (Haraway 1991; Downey and Dumit 1997) and others posthuman (Hayles 1999), it is equally vital to understand that this shift does not require the erasure of embodiment from anthropological conceptions of human subjectivity.

Ideas of the posthuman are varied and contradictory and extend from science fiction, cyberpunk, robotics, and artificial intelligence (Foster 2005; Moravec 1988, 1998; Minsky 1987; Warwick 2001, 2004) to critical social theory (Haraway 1991; Hayles 1999). The first set of sources shares a vision of transcending the limits of the human body (eliminating aging, extending physical and mental capacities) and, thus, of the posthuman as transhuman,5 beyond human. The second set, however, focuses on challenging the liberal humanist subject, that is, the conception of the human that emerged in the West during the Enlightenment. In this conception, human subjectivity is understood as stable, unitary, and autonomous and reason is seen as the defining characteristic of human being (as in Descartes famous phrase “I think, therefore I am”). It is this particular view of the human that critical social theorists seek to put in the past with the “post” of posthuman and to replace with alternate conceptions of human subjectivity, such as the image of the cyborg Donna Haraway has proposed. Haraway’s cyborg, which has been taken up in the subspecialty of “cyborg anthropology,”6 addresses three crucial boundary or category breakdowns—animal/human, organism/machine, and physical/nonphysical—that are central to the information age. Both transhumanist and posthumanist versions of the posthuman foreground technological mediation and speak to a wider set of contemporary challenges to the category human.

In How We Became Posthuman (1999), Katherine Hayles outlines competing versions of the posthuman and makes clear what is at stake in the contest between them. Hayles’s view of the posthuman is useful in theoretical, historical, and practical terms. First, she provides a framework for conceptualizing a de-centered, intermediated human subject for whom embodiment and place remain defining sources of identity and cultural difference. Second, she identifies a “teleology of disembodiment” in twentieth-century Western literary and scientific writing on information, cybernetics, and the posthuman (Hayles 1999, 22). And third, she cautions against extending this powerful cultural narrative of disembodiment—and with it the “prerogatives” of the autonomous liberal subject—“into the realm of the posthuman” (Hayles 1999, 287). Hayles uses posthuman to refer to the eclipse of a certain view of the human, not of humanity, and explicitly works to prevent the insertion of the liberal humanist subject into prevailing concepts of the posthuman. For example, she writes: “[T]he posthuman does not really mean the end of humanity. It signals instead the end of a certain conception of the human, a conception that may have applied, at best, to that fraction of humanity who had the wealth, power, and leisure to conceptualize themselves as autonomous beings exercising their will through individual agency and choice. What is lethal is not the posthuman as such but the grafting of the posthuman onto a liberal humanist view of the self” (Hayles 1999, 286). Hayles not only distinguishes the liberal humanist subject, as historically specific and powerfully constructed, from the general condition of being human but also critiques metanarratives of technological determinism and disembodied subjectivity that resurrect this culturally constructed subject in the posthuman. Such resurrection is lethal because it defines human subjectivity as independent of the material world, a self that theoretically (if not yet practically) could be downloaded to a computer and remain human. It eclipses embodiment and the ontological connection of space, time, and social being and extends the political and epistemological assumptions of the liberal humanist subject across new terrains of disembodied technopower.

Hayles applies posthuman to two very different conceptions of human subjectivity: a transhumanist vision that “configures human being so that it can be seamlessly articulated with intelligent machines” (1999, 3) and a post-humanist one that sees “the deconstruction of the liberal humanist subject as an opportunity to put back into the picture the flesh that continues to be erased in contemporary discussions about cybernetic subjects” (1999, 5). She writes:

If my nightmare is a culture inhabited by posthumans who regard their bodies as fashion accessories rather than the ground of being, my dream is a version of the posthuman that embraces the possibilities of information technologies without being seduced by fantasies of unlimited power and disembodied immortality, that recognizes and celebrates finitude as a condition of human being, and that understands human life is embedded in a material world of great complexity, one on which we depend for our continued survival. (Hayles 1999, 5)

Although both nightmare and dream represent breaks with the liberal humanist tradition, Hayles’s nightmare version of the posthuman is born of the idea that, as human beings, “we are essentially information patterns” (1999, 22; original emphasis). It adopts “a teleology of disembodiment” from the Enlightenment conception of subjectivity as seated in the conscious mind and free will, as opposed to the body. In contrast, her dream version of the posthuman contests to keep disembodiment from being rewritten in prevailing concepts of subjectivity.

For Hayles, what the posthuman means is an open contest: both transhumanist and posthumanist versions are not only possible but compete in cultural discourses, historical and contemporary. Hayles (1999, 22) puts forth a version that challenges “metanarratives about the transformation of the human into a disembodied posthuman” by replacing them “with historically contingent stories about contests between competing factions” over the disembodiment of human subjectivity. In much the same way, feminist, post-colonialist, and postmodernist anthropologists challenged metanarratives of the universal subject, replacing them with “ethnographies of the particular” (Abu-Lughod 1991, 149) and spatially, temporally, and socioculturally situated subjects (triangulated in the ontological nexus of space, time, and being). Hayles’s conception of subjectivity as “a material-informational entity” (1999, 3) is one entirely familiar to anthropologists. It is precisely this view of the contemporary human subject that, echoing Bruno Latour (1993), leads Hayles to conclude “that we have always been posthuman” (1999, 291) and Boellstorff to state that “we have always been virtual” (2008, 5). These pronouncements of continuity challenge transhumanist notions of overcoming or escaping the limits of embodied subjectivity.

Conceived to “put back into the picture the flesh that continues to be erased in contemporary discussions about cybernetic subjects,” Hayles’s version of the posthuman challenges “metanarratives about the transformation of the human into a disembodied posthuman” (Hayles 1999, 5). In similar manner, I have worked in my ethnographic account of Cyborganic to read and write the flesh back into the genealogy of contemporary forms of technosociality. In both the large-scale view of cultural history and the micro-view of particular media practices, I have spoken of various sites of subjectivity—place, presence, and colocation—as mutually co-constructed online and onground. This is how I perceive the anthropological subject in the cybernetic circuits of contemporary society. Although material-information flows decouple and reconfigure, the circuit always comes to ground in situated subjects, embodied and emplaced in the nexus of space, time, and social being. As my Cyborganic examples show, the intermediation of online and onground can work to consolidate and extend, rather than weaken, affiliations based on place and embodiment (high school, college, age cohorts). Anthropologists have long seen such affiliations as defining sources of identity, cultural difference, and insight into the human subject. In recognizing that subjectivity is constructed through mediation of material and symbolic realms, we are well positioned to contest, with Hayles, the “teleology of disembodiment” that reinserts the liberal humanist subject into conceptions of technologically mediated subjectivity and sociality. By attending to the mutual co-construction of online and onground social forms, practices, and imaginaries, we can make ethnography speak to the challenges of the posthuman.

1. Facebook (facebook.com), which claimed 845 million monthly active users worldwide in its February 2012 filing with the US Securities and Exchange Commission, and Twitter (twitter.com), which reported 140 million active users in March 2012, are two of the most popular social networking sites, but these practices and social imaginaries extend across media in many forms, collectively known as “Web 2.0” (Facebook 2012; Twitter 2012).

2. Dominic Sagolla, a key informant during my Cyborganic fieldwork, was a member of the team that created the micro-blogging service Twitter in 2006 (http://www.140characters.com/2009/01/30/how-twitter-was-born/).

3. Ontology is the branch of philosophy that studies the nature of existence or being.

4. I examine Cyborganic’s blend of entrepreneurial and utopian imaginaries and practices in my ethnography, “Communities of Innovation: Cyborganic and the Birth of Networked Social Media” (2008).

5. Transhumanism is the term for the international cultural movement toward these ends.

6. Cyborg anthropology is a subspecialty launched in 1993 and “located within the larger transdisciplinary field of science and technology studies” (Dumit and Davis-Floyd 2001, 286). See Downey and Dumit 1997 and Downey, Dumit, and Williams 1995.

Abbate, Janet. 1999. Inventing the Internet. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Abu-Lughod, Lila. 1991. “Writing against Culture.” In Recapturing Anthropology, ed. Richard G. Fox, 137–162. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press.

Appadurai, Arjun. 1990. “Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy.” Public Culture 2 (2): 1–24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/08992363-2-2-1.

Boellstorff, Tom. 2008. Coming of Age in Second Life. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Boutin, Paul. 2002. “One More Thursday Night Dinner.” Wired News. Accessed January 24, 2008. http://www.wired.com/culture/lifestyle/news/2002/05/52239.

Brand, Stewart. 1995. “We Owe It All to the Hippies.” Time, 145, special issue.

Castells, Manuel. 2001. The Internet Galaxy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Castells, Manuel, and Peter Hall. 1994. Technopoles of the World: The Making of 21st Century Industrial Complexes. London: Routledge.

Cool, Jennifer. 2008. “Communities of Innovation: Cyborganic and the Birth of Networked Social Media.” PhD diss., University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

Clifford, James. 1988. The Predicament of Culture. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Clifford, James, and George Marcus, eds. 1986. Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Crystal, David. 1987. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dibbell, Julian. 1998. My Tiny Life: Crime and Passion in a Virtual World. New York: Holt.

Downey, Gary Lee, and Joseph Dumit. 1997. “Locating and Intervening: An Introduction.” In Cyborgs and Citadels: Anthropological Interventions in Emerging Sciences and Technologies, ed. G. L. Downey and J. Dumit, 5–29. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press.

Downey, Gary Lee, Joseph Dumit, and Sarah Williams. 1995. “Cyborg Anthropology.” Cultural Anthropology 10 (2): 264–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/can.1995.10.2.02a00060.

Fabian, Johannes. 1983. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object. New York: Columbia University Press.

Facebook, Inc. 2012. Form S-1 Registration Statement, as filed with the US Securities and Exchange Commission on February 1, 2012. Accessed April 13, 2012. http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1326801/000119312512034517/d287954ds1.htm.

Figallo, Cliff. 1993. “The WELL: Small Town on the Internet Highway System.” Accessed January 24, 2008. http://www.colorado.edu/geography/gcraft/notes/ethics/html/small.town.html.

Foster, George. 1953. “What Is Folk Culture?” American Anthropologist 55 (2): l59–73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/aa.1953.55.2.02a00020.

Freiberger, Paul, and Michael Swaine. 2000. Fire in the Valley: The Making of The Personal Computer. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Geertz, Clifford. 1988. Works and Lives. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Gitelman, Lisa. 2006. Always Already New: Media, History, and the Data of Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Goodell, Jeff. 1995. “Webheads on Ramona Street.” Rolling Stone, Issue 722, November 30.

Gupta, Akhil, and James Ferguson. 1997a. “Beyond ‘Culture’: Space, Identity, and the Politics of Difference.” In Culture, Power, Place: Explorations in Critical Anthropology, ed. Akhil Gupta and James Ferguson, 33–51. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Gupta, Akhil, and James Ferguson. 1997b. “Culture, Power, Place: Ethnography at the End of an Era.” In Culture, Power, Place: Explorations in Critical Anthropology, ed. Akhil Gupta and James Ferguson, 1–29. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Gupta, Akhil, and James Ferguson. 1997c. “Discipline and Practice: ‘The Field’ as Site, Method, and Location in Anthropology.” In Anthropological Locations: Boundaries and Grounds of a Field Science, ed. Akhil Gupta and James Ferguson, 1–46. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hafner, Katie. 1997. “The Epic Saga of the WELL.” Wired (May): 98–142.

Haraway, Donna. 1991. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. London: Free Association Books.

Hayles, N. Katherine. 1999. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hymes, Dell. 1974. Reinventing Anthropology. New York: Vintage Books.

Institute for the Future (IFTF). 1997. “Images and Stories of a New Silicon Valley.” In The Outlook Project, Special Report SR-625. Menlo Park, CA: IFTF.

Ito, Mimi. 1999. “Network Localities.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for the Social Studies of Science, San Diego, CA, October 27–30.

Jakobson, Roman. 1981. Selected Writings, vol. 3: Poetry of Grammar and Grammar of Poetry, ed. Stephen Rudy. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Kenney, Martin, ed. 2000. Understanding Silicon Valley: The Anatomy of an Entrepreneurial Region. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Kollock, Peter. 1999. “The Economies of Online Cooperation: Gifts and Public Goods in Cyberspace.” In Communities in Cyberspace, ed. Marc Smith and Peter Kollock, 220–39. London: Routledge.

Latour, Bruno. 1993. We Have Never Been Modern. Trans. Catherine Porter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Malinowski, Bronislaw. 1989 [1923]. “The Problem of Meaning in Primitive Languages.” In The Meaning of Meaning, ed. C. K. Ogden and I. A. Richards, 296–336. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Marcus, George E., and Michael M.J. Fischer. 1986. Anthropology as Cultural Critique: An Experimental Moment in the Human Sciences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Markhoff, John. 2005. What the Dormouse Said: How the 60s Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry. New York: Viking.

Minsky, Marvin. 1987. The Society of Mind. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Moravec, Hans P. 1988. Mind Children: The Future of Robot and Human Intelligence. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Moravec, Hans P. 1998. Robot: Mere Machine to Transcendent Mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Redfield, Robert. 1960. The Little Community and Peasant Society and Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rheingold, Howard. 1993. The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Roszak, Theodore. 1986a. The Cult of Information: A Neo-Luddite Treatise on High-Tech, Artificial Intelligence, and the True Art of Thinking. New York: Pantheon Books.

Roszak, Theodore. 1986b. From Satori to Silicon Valley. San Francisco: Don’t Call It Frisco Press.

Rosen, Jeffrey. 2004. “Your Blog or Mine?” New York Time Magazine, December 19. Accessed January 24, 2008. http://www.nytimes.com/2004/12/19/magazine/19PHENOM.html

Ross, Andrew. 2003. No-Collar: The Human Workplace and Its Hidden Costs. New York: Basic Books.

Roy, Allan. 2001. A History of the Personal Computer: The People and the Technology. Ontario, Canada: Allan Publishing.

Said, Edward. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books.

Said, Edward. 1989. “Representing the Colonized: Anthropology’s Interlocutors.” Critical Inquiry 15 (2): 205–25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/448481.

Saxenian, AnnaLee. 1994. Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Saxenian, AnnaLee. 2006. The New Argonauts: Regional Advantage in a Global Economy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Smith, Marc A. 1992. “Voices from the WELL: The Logic of the Virtual Commons.” Unpublished manuscript. Accessed January 24, 2008. http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/soc/csoc/papers/voices/Voices.htm.

Soja, Ed. 1989. Postmodern Geographies. London: Verso.

Spitulnik, Debra. 2001. “Media.” In Key Terms in Language and Culture, ed. Alessandro Duranti, 143–45. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Stone, Allucquère Rosanne. 1991. “Will the Real Body Please Stand Up? Boundary Stories about Virtual Cultures.” In Cyberspace: The First Steps, ed. M. Benedikt, 81–118. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Stone, Allucquère Rosanne. 1995. The War of Desire and Technology at the Close of the Mechanical Age. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Turkle, S. 1984. The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Turkle, S. 1995. Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Turner, Fred. 2005. “Where the Counterculture Met the New Economy: The WELL and the Origins of Virtual Community.” Technology and Culture 46 (3): 485–512. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/tech.2005.0154.

Twitter. 2012. “Twitter Turns Six.” March 21, 2012. Accessed April 13, 2012. http://blog.twitter.com/2012/03/twitter-turns-six.html.

Warwick, Kevin. 2001. QI: The Quest for Intelligence. London: Piatkus Books.

Warwick, Kevin. 2004. I, Cyborg. Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

Wellman, Barry, and Milena Gulia. 1999. “Virtual Communities as Communities: Net Surfers Don’t Ride Alone.” In Communities in Cyberspace, ed. Marc A. Smith and Peter Kollock, 167–94. London: Routledge.

Zook, Matthew. 2005. The Geography of the Internet Industry: Venture Capital, Dotcoms and Local Knowledge. London: Blackwell Publishers.

Zuboff, Shoshana 1988. In the Age of the Smart Machine: The Future of Work and Power. New York: Basic Books.