“[The web] shares a strange feature with painting. The offsprings of painting stand there as if they are alive, but if anyone asks them anything, they remain most solemnly silent. The same is true of [the web]. You’d think they were speaking as if they had some understanding, but if you question anything that has been said because you want to learn more, it continues to signify just that very same thing forever. When it has once been [published online], every discourse roams about everywhere, reaching indiscriminately those with understanding no less than those who have no business with it, and it doesn’t know to whom it should speak and to whom it should not.”

The above paragraph is actually not about the Internet. It is about writing, and it is attributed to Plato (Plato 1997, 552). The text in brackets originally read “the written word” or “written down.” Many new technologies are accompanied by loud protests of loss of humanity, and a common thread runs through them. Plato encapsulates the heart of the oft-repeated argument with his claim that writing robbed words of their soul by freezing them into an immutable medium rather than the flesh and blood human who can talk, respond, and listen in context. As I will argue, this unease stems from the fundamental duality of being human: we are at once embodied and symbolic. Some technologies allow us to separate those two aspects, thereby creating the gap Plato laments: words without bodies.

DOI: 10.5876/9781607321705.c02

Once the thought and the human are separated, as in writing, the thought then enters a perilous territory. Disembodied meaning, it seems, cannot hold on to its context and can now be deconstructed, reinterpreted, misapplied, rewritten, and, even worse, used ironically, as I did above, to make a point that might in the end counter the original intent of the author, if one can still speak of authors and original intents. Even so, the reification of the word implies neither loss nor transcendence of humanity.

The proliferation of digital technologies has made us no more post-human than the invention of writing or the creation of those breathtaking Paleolithic cave paintings at Chauvet. Neither the first totem nor the typewriter, nor the telegraph, nor the pyramids, nor the libraries of Alexandria, nor the Internet, nor the cyborg-visions make us any more posthuman than before. The essence of humanity is that we have always been both symbolic and embodied. This, by itself, cannot be interpreted as post-, because there was never a pre- in which humans were not simultaneously and inseparably both symbolic and embodied.

Or maybe, said alternatively, we were always posthuman. The symbolic capacity of humanity has always meant that it was possible to separate and extend the word from the body. Once separated, or more accurately, alienated, from the living creator, the word can now stand on its own—or, contrary-wise, pace Plato, no longer attached to life, it dies. McLuhan (1962) famously compared all media to extensions of human capabilities—the eye, the ear, the hand, the skin. Finally, through information technologies, we have symbol manipulation technologies that allow us to extend our cognitive and social capabilities and do so in a networked manner.

A related, but not identical question is about the extension of our capabilities. Unlike almost all other animals, humans intrinsically extended their abilities through the use of tools, social organization, and their ability to externalize the symbolic, as discussed in this chapter. Our symbolic nature directly supports our capacity for extension of our abilities. A corollary of the argument presented here is that we are no less human than the first time an ancestor picked up a stick to extend an arm. On the other hand, this extension, like all the others, is surely not without consequence.

To understand the almost visceral reaction of Plato and many commentators after him in response to these technologies of extension, alienation, and replication of our symbolic and cognitive capabilities, we must return to the source of this unease. There are three interrelated dynamics at play: externalization and reification of the symbolic, mediation of human interaction, and extension of human capabilities.

As stated, a core tension of being human flows from the fact that humans are embodied creatures as well as symbolic beings. As embodied beings, we are necessarily finite and limited. As symbolic beings, we can also externalize and freeze that which emanates from our minds. However, our minds are not attached to our bodies as an externality, merely an add-on or an option, but as part of our flesh, as lowly or as glorious as every other part of that mesh of blood, nerves, muscles, bones, cartilage, and skin that we are composed of. That truth is often difficult to assimilate, especially since the symbols that emanate from this flesh can be exteriorized and reified and can be drawn on caves, carved on stones, scribbled on papyrus, written on paper, typed on keyboards, stored in magnetic disks, and raised in Braille. Our symbols can be sent into space, buried in time capsules, stored in archives, and carved into mountains. All of this generates the haunting temptation of overcoming that finitude of the embodiment, which generates in some an awe and yearning for a desire to transcend the flesh and in others, as in the opening vignette by Plato, disgust with the perceived hollowness of the symbol that is no longer an inseparable part of the human lifeworld.

Hayles warns us against ignoring embodiment when she talks of her nightmare of a culture “inhabited by posthumans who regard their bodies as fashion accessories rather than the ground of being” and her dream of a “a posthuman that embraces the possibilities of information technologies without being seduced by fantasies of unlimited power and disembodied immortality” (Hayles 1999, 5). She is warning about the temptation to imagine ourselves as information that “leaves behind the body,” an understanding conceptualizing a subjectivity resting on a mind/body duality that she argues is rooted in the dualist conception of humanity in which the mind is primary, and the body, merely a vessel. Indeed, if “I” only refers to this mind, an abstraction, and if the body at most an input/output mechanism, why not get rid of it or replace it with another? If our bodies are vats for our brains, can we perhaps pursue better vats?

Indeed, isn’t leaving behind the body what cyberculture is all about? Many prominent and early theorists of cyberspace claimed that the Internet has become a place where the body becomes irrelevant, or at least much less relevant. Stone (1991, 101) provocatively asked “the real body to stand up”:

If the information age is an extension of the industrial age, with the passage of time the split between the body and the subject should grow more pronounced still. But in the fourth epoch the split is simultaneously growing and disappearing. The socioepistemic mechanism by which bodies mean is undergoing a deep restructuring in the latter part of the twentieth century, finally fulfilling the furthest extent of the isolation of those bodies through which its domination is authorized and secured.

Similarly, when Turkle examined the nature of community in the early online communities like the WELL, she argued that cyberspace may be the realization of the postmodern identity that is decentered, multiple, and fragmented. Turkle affirms that although these developments precede the Internet, cyberspace now plays a prominent role in this story “of the eroding boundaries between the real and the virtual, the animate and inanimate, the unitary and multiple self” (Turkle, 1995, 10).

In the daily practice of many computer users, windows have become a powerful metaphor for thinking about the self as a multiple, distributed system. The self is no longer playing different roles in different settings at different times ... The life practice of windows is that of a decentered self that exists in many worlds and plays many roles at the same time ... As more people spend more time in these virtual spaces, some go so far as to challenge the idea of giving any priority to RL [Real Life] at all. “After all,” says one dedicated MUD [multi-user dungeon] player and IRC [Internet relay chat] user, “why grant such superior status to the self that has the body when the selves that don’t have bodies are able to have different kinds of experiences?” (Turkle, 1995, 14)

However, there are reasons that this narrative is no longer helpful in understanding the profound changes brought about by the integration of the Internet into the lives of hundreds of millions of people. Early users who formed the center of those studies were very different from the general populace at the time: more male, more technically oriented, racially homogeneous, fairly well-off, and generally young and of particular cultural leanings (with an ethos of openness, a fondness for some version of libertarian politics, plus a fascination with the technical). It is also possible that identity experimentation was exactly the reason they were drawn to the early communities. In other words, what we saw was not necessarily a consequence of the Internet but the emergence of a particular community that was interested in that particular genre; therefore, the results were more of a “selection” effect rather than “treatment” effect. In contrast, current Internet users are very much like the general populace and we have not seen a mass rise in identity experimentation as a result of mass adoption of cybertools. And this is even truer for the younger populations, with obvious implications for the future. The Internet is no longer an exotic space where identity experimentation reigns, although this experimentation, of course, continues to exist.

However, it is important to note that the continuum from managing multiple social roles and audiences to identity experimentation has always been part of the human experience. Indeed, persons do not act the same way with their mothers as they do with their bosses or their romantic partners; those who did would be marked as deviant, without understanding of human social norms and conventions, sociopathic. Goffman (1959) extensively theorized the way we manage different audiences by using the language of dramaturgy and theater; if he were writing today, he might have talked about having online profiles and social presence. However, different social roles and the ability to adopt different online personas do not lead to a multiple or fractured self mainly because the body, in the end, centers and unites us. I am not arguing that embodiment homogenizes us or removes the conflicting desires, roles, and yearnings within the individual that is part of the human condition. I am, however, contesting the notion that the mere act of typing on a keyboard creates on ontological split within the body.

The obvious question then is what are the implications of increasing immersion and moving from typing to being swallowed by technologies like goggles, bodysuits, skin-input machines, and perhaps later the further integration of flesh and machines? Are the people who spend most of their waking hours playing immersive video games the vanguard of the future or mere remnants of a subculture that has always been with us? This question will no doubt continue playing out as technology evolves; hence, it is important to have these debates now.

Last, these early analyses of the Internet’s ability to multiply selves depend on a conceptualization of the Internet as a separate, virtual world; thus, in effect, we have a double world—the world and the cyberspace. (Such an implicit stance often appears when people contrast the “virtual” world with the “real” world.) This is a corollary of the desire to provide the symbolic the same ontological status as the embodied human from which the symbol emanates. However, as a theoretical stance, the concept of the “virtual world” cannot be defended unless one is willing to extend such world-doubling qualities to writing, to telephone, and, indeed, to those cave paintings. It is only through the ontological equivalence of the reified, exteriorized symbol—the text, the file, the picture—with that of the embodied originator that we can truly equate typing as opening the door to separate identities, rather than as different segments of a complex identity. I choose to follow Hayles and declare that humans are intrinsically and inseparably embodied. As Wynn and Katz (1997) ask, “how can we call them ‘selves’ if they lack the situated intelligence of historical embodiment?” Uncoincidentally, death is often associated with the reification of symbols and words. As Ong notes, “[o]ne of the most startling paradoxes inherent in writing is its close association with death ... The paradox lies in the fact that the deadness of the text, its removal from the living human lifeworld, its rigid visual fixity, assures its endurance and its potential for being resurrected into limitless living contexts by a potentially infinite number of living readers” (Ong 2002, 230–71).

I have claimed that early Internet theorizations are no longer helpful because current modalities of Internet use in this era of widespread “online sociality,” in which increasing portions of our social interactions are mediated through social media, offer a very different type of experience. To explain the ramifications of recent developments with regard to implications for identity experimentation, I will examine one particular form of social media where there is a mixture of interactivity, responsiveness, and reification: profile-based social media sites. These popular Internet applications provide some of the most illuminating case studies of the consequences of mediation through platforms specifically geared toward projecting an identity. These sites are alternatively referred to as online social networking sites or online social network sites (boyd and Ellison 2007): “We define social network sites as web-based services that allow individuals to (1) construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system. The nature and nomenclature of these connections may vary from site to site.” The most prominent of these applications are Facebook and Myspace, which have recently been joined by Twitter; they constitute the most popular destinations on the Internet except for search engines, which are, of course, less of a destination and more of a tool for reaching some other destination. Facebook started out as a Harvard-only site, quickly spread to other colleges, and then was later expanded to high schools and, at last, all of the United States and the world, with about 1 billion users. Myspace, although not as popular as Facebook, remains a vibrant site with about 100 million users, although it receives less press coverage. Other sites that are popular outside the United States, such as Orkut, each have about 100 million users. Although there has been debate about the segregation of populations among social network sites, with Facebook seen as reflecting a hegemonic, wealthier, more white culture (boyd 2009) compared to Myspace, which is associated more with minority and poorer students (Hargittai 2007), more recent reports and numbers suggest that this situation may have changed with more people acquiring a Facebook profile, at least in the United States (Chang et al. 2010). It is perhaps most accurate to say that Facebook has become increasingly mundane and domesticated.

I have been conducting extensive research including surveys, interviews, focus groups, as well as ethnographic observations on social media practices of college youth since around the inception of Facebook. Based on more than 1,500 surveys, hundreds of interviews, as well as an ongoing dialogue with a variety of users of such sites as well as “virtual ethnography,” I have been examining the myriad ways in which social network sites have reconfigured social practices, especially among college-age youth. This research has involved repeated surveys as well as continuation of interviews every year since 2005 until submission of this chapter in 2011.

This research shows that having a profile on a social network site has become a norm among this population (Tufekci 2008a, 2008b). There are fewer and fewer college students who are not represented on Facebook and these students tend to be either nontraditional students or recent immigrants whose families strongly disapprove of such activities. Students put in a lot of labor to create profiles, posting a plethora of information in an attempt to project an online persona. In my studies (Tufekci 2008a, 2008b), I found that, initially, 95 percent of the students on Facebook used their real names and engaged in enormous amounts of disclosure—about three quarters indicated their favorite music or movies as well as their romantic status, indicating whether they were currently single, in a relationship, engaged, married, or even, as a standard option “it’s complicated.” This percentage has recently been decreasing. In my latest study in December 2010, about 10 percent of the 450 students surveyed said that they were using a nickname, and another 10 percent reported using a variety of strategies to decrease name recognition. However, that still leaves an overwhelming majority, perhaps as high as 80 percent, who use their real names.

I also found that although privacy concerns may have impeded some students’ willingness to join these sites, once on the sites, those concerned with privacy were no less likely to disclose important information than those that were less concerned. Logistic regression (reported in Tufekci 2008a) showed that privacy concerns had little effect on behavior within the sites once a student joined Facebook. This speaks to the importance of norms in negotiating behavior in online environments; once joined, behavior tends to converge toward the norm of the existing environment.

A persona on these sites is not solely controlled by owner of the profile but rather co-created through social networks. Just as Goffman (1959) describes it, identity formation is a collective process that relies on the participation, assent, and acquiescence of the social circle. There are multiple means through which the social networks within which people are embedded are implicated in the creation and affirmation of identity. At the simplest level, the list of Facebook friends is composed of people who have accepted the request and confirmed a connection. A person’s list of friends is perhaps the most significant display of how identity is constructed collectively. Furthermore, the friends, the strength of which may range from weak acquaintances to very close friends and family, actively contribute to the profile through means that range from online-only activities, such as writing on a person’s “wall,” to those that merge the online and offline worlds even more thoroughly, such as posting photos and “tagging” the person, that is, identifying the face/body pictured in the physical world and linking it to the online profile.

The persona that is co-constructed with the person’s social network on these sites is thus deeply integrated with the offline-world. In fact, ironically, the body is more, not less, present and on display through social media. Of all sites on the Internet, Facebook is the platform with the most photographs uploaded on any given day, far surpassing photo-dedicated websites such as Flickr. The ubiquity of cell phones and smart mobile devices with image capturing capabilities and the convergence of offline and online worlds have not facilitated the ascendance of the word at the expense of the body. As Hayles (1999) would put it, information has not been able to leave the body behind.

The female body is especially on display on Facebook. As part and parcel of mainstream culture, these sites reflect the ascendance of “raunch culture,” a phenomenon noted by many critics (Levy 2006). Of course, it is a mistake to assume that all profiles display certain characteristics. Indeed, my main argument is that Facebook often represents deep integration with the offline world and, as such, is subject to the same variety of people, cultures and subcultures, trends and fads, and other vagaries and attributes of life in general. There is no “one” Facebook because there is no “One” Culture.

The Internet, unlike the physical world, allows for potentially permanent storage, easy searchability, link-based navigation, and data aggregation of previously unthinkable magnitude (Solove 2007). Combined with offline-online integration, the result has been an explosion of surveillance and monitoring. By operating on the Internet, a medium that stretches time through persistence so that the past is always available and collapses spaces so that different contexts can overlap, the current social media practices have resulted in shrinking the spaces for maneuverability and negotiation of different social roles and identity.

Thus, the prevalence of digital photographs, the affordances of tagging, and the convergence of media make everyone a potential spy, voyeur, and documenter of life. On most college campuses, a young person at a gathering of any sort is likely to be photographed, and that photo will be uploaded and tagged, perhaps within the hour. Such ubiquity of peer surveillance, which I dub “grassroots surveillance,” has resulted in a particularly ironic twist with regard to the possibility of “identity play” in the age of ubiquitous social media: it is harder, not easier.

For example, in my latest survey in December 2010 of 450 college students, about 73 percent report having had their profile found by someone unwanted, 71 percent report unwanted photos posted by others, and 38 percent report having someone become upset with them because of a photo with someone else. About 71 percent report knowing of fights between boyfriends and girlfriends caused by Facebook postings, and about 50 percent had friends who broke up romantic relationships and another 65 percent witnessed fights between friends because of Facebook postings. Similarly, about 52 percent knew of friends who had fights with parents over Facebook. When asked about their own experiences, about 27 percent reported fighting with a romantic partner over Facebook, about 8 percent had ended a relationship because of it, and 25 percent fought with a parent whereas another 17 percent fought with a parent. A staggering 58 percent had caught their friends in a lie through Facebook.

This pattern of fights, eruptions of jealousy over photographs of boyfriends and girlfriends in the company of inappropriate others, friends caught in lies, unintended disclosures, unmasked pretenses, and all manners of otherwise likely innocuous—and likely ubiquitous—forms of concealment and nondisclosure would have passed without comment, or not been noticed at all, had it not been for social media-based surveillance.

“Facebook is the devil,” declared one of the young adults I talked to as part of this multi-year, multi-method research project. Most young adults I have talked with report that social media has made it harder for them to engage in identity experimentation without taking elaborate care, even maintaining separate profiles for different audiences; monitoring carefully and continuously all profiles for unintended leaks, disclosures, crossing of wires, inappropriate photographs, unwelcome wall comments, and unfriendly activity; and guarding against parents, relatives, potential employers, college-admission boards, coaches, and other friendly and unfriendly authority figures that one may now encounter. The collapse of different contexts and continuation of links across geographical and temporal shifts (keeping high school friends as Facebook friends in college) make it harder to evolve without explicitly leaving behind others who were once close. The problem is not just hierarchical surveillance by those with power of those with less, but the strong pressure of peer surveillance and the ubiquitous co-monitoring activities of peers through social media.

New ways of managing this grassroots surveillance are emerging, and new norms and manners of interaction in response have been evolving for years. However, as of this writing, the cultural toolkit (Swidler 1986) of young adults has not yet completely absorbed the ramifications of this level of surveillance, resulting in strong tensions, disruptions, and conflict. Of course, in this context I refer to the hegemonic culture in college campuses, which includes other online environments and communities associated with them, such as that of Anonymous examined by Wesch elsewhere in this volume; diasporic avatars in immersive virtual worlds, such as Second Life discussed by Gajjala; or the intricacies of the popular “massively multiplayer online game” World of Warcraft probed by Graffam. All of these examples have developed completely different and, indeed, orthogonal practices compared with most Facebook users. Facebook has more in common with the Cyberorganic community examined by Cool (this volume) in its tendency for offline/online integration, which helps create the identity-constraining dynamic discussed in this chapter. In the end, the Internet is neither homogeneous nor a single thing. However, as with all societies, it incorporates dominant cultural spaces as well as subcultures and countercultures. In this particular essay, I have discussed aspects that have become mundane and domesticated, at least for almost all college students in the United States.

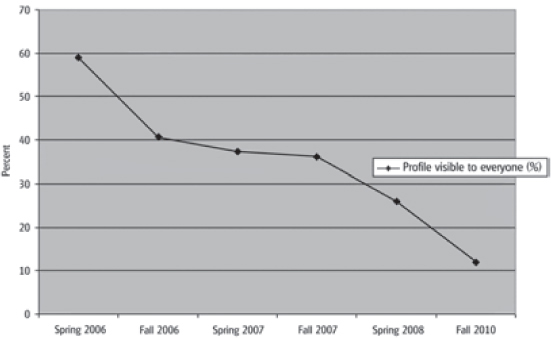

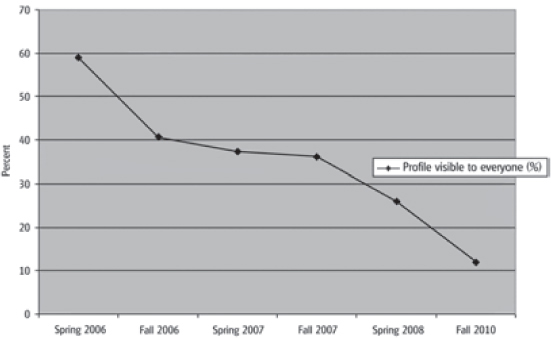

Visibility of profile to everyone.

It is also important to note that the emergence of grassroots surveillance is not the same as the often repeated, but incorrect, notion that young people are giving up on privacy or that they do not care. Rather, my findings show that they are struggling to adapt to a rapidly changing digital ground—but young people are actively responding to these changes. For example, Figure 2.1 shows the percentage of Facebook users who have their profiles visible to everyone. This percent dropped from nearly 60 percent to barely 10 percent in just a few years as young people learned about and adjusted their privacy settings. This, too, remains an area for scholars to watch as it evolves.

Another important aspect to examine is mediated sociality. Words, once separated, can also be transmitted to other people within social contexts. Such mediation of social interaction is increasingly not just common but routine and unremarked. E-mail, IM, phone, Facebook, text messages, tweets, chats, Skype, and so forth are no longer exotic or rare; rather, they are thoroughly integrated into the lives of hundreds of millions, if not billions, of people. What are some of the implications of this increasing incorporation of digital mediation into our sociality?

We must not lump all forms of mediation into one undifferentiated pile because they differ, especially with regard to the heart of Plato’s lament: interactivity. Interactivity can be perceived as a continuum, since conventional letters are also interactive in the sense that a conversation can go back and forth. However, the sense of interaction for humans is rooted, as is everything else, in the embodied person who perceives “interactive” to mean “immediate,” as defined in blinks of the eye rather than hours, days, or weeks. Further, it matters whether the transmitted portion remains close to the human life-world, as voice and images do, or is more abstract, as in letters, e-mails, texts, and instant messaging. The disembodied voice of the telephone, although it departs from the instinctive human notion of interactivity, remains closer to it than the frozen words of the letter or e-mail. The Internet, of course, is not any one of these things and can incorporate multiple modalities: a real-time video chat, audio chat, text chat, static web page, blog with comments threads, online social network site, discussion board, instant-messaging application, among others. Each one might have a different impact on the reception of the message, the perception about the communication, and the quality of the social interaction that took place. Instant messaging, for example, is more likely to create the feeling that a person is there, whereas e-mail may not.

My research project included surveys in 2007, 2008, and 2010 and examined whether respondents thought friendship only through online mediation was possible. In 817 surveys in 2007–2008 and 450 surveys in 2010, I found a consistent polarization among the young adults surveyed in this study. About half expressed disbelief that it was possible to be friends using only online means whereas the other half were open, and even warm, to the idea. This difference was not necessarily a function of competence with the Internet; both groups used social media in roughly equal amounts.

I have proposed the trait cyberasociality, which I define as “the inability or unwillingness of some people to relate to others via social media as they do when physically present.” On the opposite end of the spectrum are the hypersocial, a (small) group that feels a deeper connection was more possible through online methods, because the distractions of appearance and the potential concomitant judgments were absent and conversation, rather than physical attributes, dominated the encounter. This group echoed Walther (1996), who found that text-only interaction can create a hyperpersonal bond.

For the cyberasocial, however, lack of physical copresence makes it difficult, if not impossible, to respond to the interaction if they could not ground it in face-to-face presence. For these people, face-to-face interaction has inimitable features that simply cannot be replicated or replaced by any other form of communication. It is possible that preference for or avoidance of online sociality brings to the fore certain personality attributes that were simply not as crucial in the pre-Internet era and are thus not neatly quantified by existing measures and not reflected cleanly in traditional demographics.

Importantly, cyberasociality was not correlated with offline sociality. That is, statistical analysis showed that a person’s cyberasociability was not predictable by the number of offline friends they had or the amount of time they spent with them. Thus, my study contradicted the commonly floated idea that “people who are more social offline are more social online, as well as the notion that it is only the social misfits who use social media to make new friends” (Tufekci 2010, 170). In other words, it was not the social rich getting richer online; rather, emerging dispositions of the digital age were starting to play a role.

Could cyberasociality be a personality trait that can only become visible with the emergence of mediated communication, similar to dyslexia, which only became an issue after writing was invented? Can this explain the ongoing debate about whether online methods are suitable for deep friendships (Deresiewicz 2009)? Babies as young as two weeks old respond differently to icons arranged as a face, with an identifiable pair of eyes, a nose, and a mouth, compared to the same icons arranged randomly. Eye contact, smiles, gestures, and physical copresence evoke strong responses. Some facial expressions such as smiles and frowns have been demonstrated to be universal, strengthening the case that our sociality and our biology are deeply connected (Ekman 1980).

It makes sense that our social responsiveness is not just an artifact or an afterthought of our cognitive capacities, something we can easily “will” ourselves to evoke because we know that there is a person on the other end of the mediated communication. In other words, we do not merely see a person and then decide to react; rather, the presence of a person evokes sociability in ways deeply buried in our human endowment. However, for some people, just the knowledge that the words appearing on the screen were typed by a person may be enough to summon that particular feeling of sociality and human connection. We all require a sense of presence to connect, but “presence” is a subjective, variable experience. For the moment, we need to contemplate the consequences of an increasingly digital world in which some people are unable or unwilling to channel sociability in response to a mediated interaction.

Cyberasociality can perhaps be seen as the third level of digital divide. Scholars have long documented a divide in access to computing technologies (first level), as well as disparities in skills and competence (Hargittai 2007). Cyberasociality, however, is better seen as the third level of digital difference, rather than inequity, although the divide may still disadvantage those who are cyberasocial, either by choice or through preference.

The limits of human sociality were famously explored by Robin Dunbar (1998), who concluded that the human brain—more specifically, the neocortex—is capable of keeping track of no more than 150 social relations with their concomitant ties and levels of reciprocity (Dunbar 1998; Gilbert and Karahalios 2009). Similar to the way a stick extends and strengthens the arm and the written word extends memory, do social media extend our capability for sociality and leave behind those who cannot or will not use it to its full capacity?

It is too early to reach conclusions regarding this new technology. Early research shows that people, on average, tend to have around 120 Facebook friends—a number remarkably similar to Dunbar’s. Facebook friends, of course, can range from the weakest ties to the strongest. Perhaps ironically, recent research also shows that the number of closest confidants of Americans has plummeted (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, and Brashears 2006, 2009), although Internet users tend to maintain more confidants (Hampton, Sessions, and Her 2011). Network researchers generally confirm that there is little reason to think that people have more close relationships than they did a century ago or even before (Christakis and Fowler 2009), and our closest ties may remain at fairly similar levels to those of even our hunter-gatherer ancestors (Apicella et al. 2012).

In the end, technology may indeed enable us to keep in touch with more people or maintain numerous connections at professional networking sites, such as LinkedIn, but the size of our closest circles and the number of those nearest and dearest to us does not seem to have been affected much. That said, our broader circle may now be much larger and include persons scattered around the globe rather than be just members of a small tribe with whom we travel throughout our lives. Digital mediation changes everything, and yet it changes so little. The size of our capacity and ability for affection and bonding remains grounded in our humanness. And that perhaps is the most important conclusion. “Faster, higher, and stronger” through technology may be tempting, but we are, as we have always been, human and our limits transcend technology. We are, as we always were, human, all too human.

Apicella, Coren L., Frank W. Marlowe, James H. Flowler, and Nicholas A. Christakis. 2012. “Social Networks and Cooperation in Hunter-Gatherers.” Nature 481 (7382): 497–501. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature10736.

boyd, danah. 2009. “White Flight in Networked Publics? How Race and Class Shaped American Teen Engagement with MySpace and Facebook.” In Digital Race Anthology, ed. Laura Nakamura and Peter Chow-White. New York: Routledge.

boyd, danah, and Nicole Ellison. 2007. “Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 13 (1): 210–30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x.

Chang, Jonathan, Itamar Rosenn, Lars Backstrom, and Cameron Marlow. 2010. “Epluribus: Ethnicity on Social Networks.” International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media. Accessed June 4, 2010, http://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/ICWSM/ICWSM10/paper/view/1534.

Christakis, Nicholas, and James Fowler. 2009. Connected: The Surprising Power of Our Social Networks and How They Shape Our Lives. New York: Little, Brown.

Deresiewicz, William. 2009. “Faux Friendship.” The Chronicle Review. December 6. http://chronicle.com/article/Faux-Friendship/49308/.

Dunbar, Robert. 1998. Grooming, Gossip, and the Evolution of Language. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ekman, Paul. 1980. The Face of Man: Expressions of Universal Emotions in a New Guinea Village. New York: Garland STPM Press.

Gilbert, Eric, and Karrie Karahalios. 2009. “Predicting Tie Strength with Social Media.” Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 211–220.

Goffman, Erving. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Garden City, NY: Doubleday Anchor Books.

Hampton, Keith, Lauren F. Sessions, and Eun Ja Her. 2011. “Core Networks, Social Isolation, and New Media: Internet and Mobile Phone Use, Network Size, and Diversity.” Information Communication and Society 14 (1): 130–55. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2010.513417.

Hargittai, Esther. 2007. “Whose Space? Differences Among Users and Non-Users of Social Network Sites.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 13 (1): 276–97. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00396.x.

Hayles, Katherine. 1999. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Levy, Ariel. 2006. Female Chauvinist Pigs: Women and the Rise of Raunch Culture. New York: Simon and Schuster.

McLuhan, Marshall. 1962. The Gutenberg Galaxy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

McPherson, Miller, Lynn Smith-Lovin, and Matthew Brashears. 2006. “Social Isolation in America: Changes in Core Discussion Networks over Two Decades.” American Sociological Review 71 (3): 353–75. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/000312240607100301.

McPherson, Miller, Lynn Smith-Lovin, and Matthew Brashears. 2009. “Models and Marginals: Using Survey Evidence to Study Social Networks.” American Sociological Review 74 (4): 670–81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/000312240907400409.

Ong, Walter. 2002. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. New York: Routledge.

Plato. 1997. Plato: Complete Works. Ed. J. M. Cooper and D. S. Hutchinson. Indianapolis: Hackett.

Solove, Daniel. 2007. The Future of Reputation: Gossip, Rumor, and Privacy on the Internet. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Stone, Rosanne. 1991. “Will the Real Body Please Stand Up?” In Cyberspace: First Steps, ed. Michael Benedikt. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. http://molodiez.org/net/real_body2.html.

Swidler, Ann. 1986. “Culture in Action: Symbols and Strategies.” American Sociological Review 51 (2): 273–86. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2095521.

Tufekci, Zeynep. 2008a. “Grooming, Gossip, Facebook and Myspace.” Information Communication and Society 11 (4): 544–64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13691180801999050.

Tufekci, Zeynep. 2008b. “Can You See Me Now? Audience and Disclosure Regulation in Online Social Network Sites.” Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 28 (1): 20–36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0270467607311484.

Tufekci, Zeynep. 2010. “Who Acquires Friends through Social Media and Why? ‘Rich Get Richer’ versus ‘Seek and Ye Shall Find.’” International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media. Accessed June 4, 2010, http://www.aaai.org/ocs/index.php/ICWSM/ICWSM10/paper/view/1525.

Turkle, Sherry. 1995. Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Walther, Joseph. 1996. “Computer-Mediated Communication: Impersonal, Interpersonal, and Hyperpersonal Interaction.” Communication Research 23 (1): 3–43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/009365096023001001.

Wynn, Eleanor, and James Katz, and the Eleanor Wynn James e. Katz. 1997. “Hyper-bole over Cyberspace: Self-Presentation and Social Boundaries in Internet Home Pages and Discourse.” Information Society 13 (4): 297–327. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/019722497129043.