Mediating Indian Diasporas across Generations

Since early 1990s, a time that coincides with global access to the Internet in the form of the World Wide Web, there have been certain rearticulations of categories of diasporas from the South Asian region through techno-mediation. Such rearticulations are based in the naming of diasporas through the politics of a nation-state whereas others are based in the naming of diasporas through transnational linkages along the lines of struggle for a nation-state (as in the case of Tamil Eelam diasporas). In addition, these diasporas (as is the case with previous diasporas) are shaped by labor needs within various economic contexts. Digitally produced and circulated media play a significant role in such South Asian diasporas. Thus, in the case of the Indian nation-state and diasporas mediated through digital online media, “New Bollywood” invokes nostalgia for an imagined homeland for the non-resident Indian (NRI) population (Booth 2008). At the same time, a particular section of the NRI population is being encouraged to “return home” to establish transnational industry and business in India (Mallapragada 2000). Still other sections of the population are being mobilized as part of an offshore labor force that keeps their bodies in one social context and requires their labor, services, and skills to be projected, in a seemingly disembodied manner, into other social contexts. The term “diaspora,” in turn, has been mobilized by the Indian government and industry to build particular types of transnational connections. In this context, the phrase “digital diaspora” becomes a way to build networks of transnational capital and labor.

DOI: 10.5876/9781607321705.c06

Through these articulations and rearticulations of selves, the issue of authentic “Indian” identity is continually negotiated in a productive tension between enactment and representation. Individuals and communities joining (i.e., reluctantly or voluntarily seeking membership through compliance or resisting existing formations through explicit countering of previous articulations) such diasporic communities continue to use media and technology in the re-creation of community and identity amid host environments that sometimes oppress and sometimes liberate. Present-day new waves of globalization offer opportunities for, and require mobility of, labor and capital through digital environments and produce variations of split and post-liberal human identities. Digitally produced and circulated media play a significant role in such diasporas. Within such an overall context, this chapter performatively and descriptively engages instances of (post-)human instances/viewpoints of living online, spanning three to four generations of Internet users of Indian origin as encountered by Radhika during continuing ethnographies in these environments.

Working from this background, we start by discussing how notions of nostalgia and presence shift through disembodiment and reembodiment at mediated interfaces starting with a narration of “splitting” and “multiplying” in diaspora in pre-digital times through what we refer to as communicative spaces of media. This splitting, layering, and multiplying are explored further through an examination of specific encounters with online/offline young men and women who identify as being of Indian origin. Much of the shaping of online “Indianness” happens through subconscious and affective linkages and immersion based in how Indian-identified artifacts, practices, sound-bites, and images travel through digital worlds such as Second Life, Facebook, LiveJournal, blogs, YouTube video sharing, production of Machinima, and so on. These are, in turn, actualized materially and discursively online and offline as “Indian” or “not Indian” as larger community formations and groups authenticate particular behaviors, signifiers, and characteristics as “Indian.” The splitting at the interface that we locate in this chapter leads to a different way of understanding how community is simultaneously imagined, lived, and enacted as we move in and out of multiple mediated environments. This sort of imagining of community through mediated networks linked nodally is based in different mediated economic and social formations than that implied by Benedict Anderson’s (2006) notion of imagined community. It is this shift that produces the authentication of the posthuman diasporic Indian and allows the idea of “Indian digital diasporas” to emerge in the current socioeconomic and technical moment in time and space.

In this section, Radhika draws on her experience as a “nomad” in pre-digital times (offline) to illustrate what is meant by “communicative spaces of diaspora.” The offline pre-digital communicative spaces of diaspora she refers to are based in the post-1960s flow of professional, mostly upper caste and upper class, Western-educated labor away from South Asia toward modernity, internationalization, and development. Post-1960s imagining of community, for instance, materialized through communicative spaces of diaspora, where “home” was a romanticized, frozen place remembered through nostalgic storying and through radio, LP records, slides, photographs, home movies, and occasionally televised and screened movies from the subcontinent.

Diasporic affect based in nostalgia for a geographical location of home fostered connections between diasporic groups that identified as originating from the South Asian subcontinent with subgroups formed along national, religious, linguistic, and sometimes even caste lines. Post-1960s migration from the South Asian subcontinent was also a response to international modernization. The United Nations (UN), and related global nongovernmental organizations, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) came to be seen as global facilitators of development and upliftment of “underdeveloped” nations, while the United States rose to the status of superpower. It is well known that the 1965 Immigration Act was a result of US labor needs, as well as the political need for the United States to be perceived as more open than before.

In the post-1960s waves of migrations, “South Asian” group identities were more strongly forged than in previous generations as a response to the professional and social expectations of that time. In cosmopolitan international social gatherings, such as those attended by a growing number of UN officials from the subcontinent, exclusive identification along national, religious, or caste identities (as in “Pakistani,” “Indian,” “Hindu,” “Muslim,” “Brahmin,” and so on) were discouraged through social cues pointing to the non-modern nature of such ways of identifying. Rather, religious and linguistic diversity was celebrated as part of world cultures. Further, this modern space was urban-centric. The rural could be romanticized when spoken of, but South Asian “third-world” rural practices in everyday living were considered unhygienic, backward, and primitive. The rural is thus automatically positioned as the opposite of modern.

The professional class and their families therefore learned to police themselves into the appropriate cosmopolitan, modern sociocultural behaviors expected of them in such public international spaces. Religious, regional, and rural daily practices, if they persisted, were contained in the private space of the home, where the woman became the keeper of culture. Uma Narayan, for instance, writes of the “dark side of epistemic privilege” and of the “double vision” generated through the code-switching necessitated by continual negotiation of multiple contexts (Narayan 1990, 265). The double vision that results from the encounters with spaces of individualization and that lead to voicing on the Internet could result in a variety of negotiations in relation to cultural oppression during the transition from one kind of community-based hierarchy to another.

Entering new spaces generally requires a process of negotiating multiple contexts through a kaleidoscope of lenses as the (re)coding of self and surroundings happens in various ways. Hierarchies constructed through the process of shifting into new cultures surface when those who have and those who do not have the sociocultural, socioeconomic, and techno capital required to produce and consume information and/or products in that space become positioned accordingly. Negotiating enactments and representations of identity can result in a splitting of the subject who is transitioning betwixt and between spaces of (un)familiarity and nostalgia. Spaces of transition, whether they occur online in digitally connected communities or offline in physically present ones, require a shifting of literacies that subsequently impacts performances and politics of identity in both online and offline spaces. In global online networks that constitute “new types of global politics and subjectivities,” identities become positioned physically and virtually in the “oppositional politics” of transnational online labor (Sassen 2004, 1–2).

Identities produced within digital contexts enabled by computer software and hardware are made possible through the coproduction of sociocultural digital place and global networks involving time-space compression. These sociocultural contexts are coproduced by inhabitants who access these contexts. The sociocultural literacies of these inhabitants determine the kinds of free labor they contribute toward the building of these spaces (Terranova 2004). The continued inhabiting of these spaces leads to a reorganization of social space and everyday practice similar to that experience by call-center workers from India who are tuned in to time zones and cultural practices in the Western worlds as described by Ananda Mitra (2008) in his work on outsourced call workers. Therefore, they experience a social, affective transformation that orients them toward life in global multicultural communities similar to those encountered in a diaspora. Further, these online residents also experience displacement and disorientation similar to that produced in social encounters within diaspora.

However, this is still not the same as that encountered by traveling bodies. Thus, although the digital diasporas produced through online encounters of global environments can effectively simulate diasporic life and even actually change the everyday praxis of offline bodies, the experience is not fully that of those in a diaspora. Simultaneously, the digital spaces are also inhabited by younger generations from various diasporas the world over. Contact zones of geographically dispersed diasporas from South Asia are produced in the encounter between these differently located digital subjects. Thus, these spaces can be considered transitional places orienting digital subjects toward a particular kind of multicultural globalization. They provide the entry point for new and emerging digital forces connecting from non-global geographical areas of South Asia that are not fully rural but neither are they fully urban and global in the way scholars have described global cities.

These present generations of global workers thus live in a dynamic moment in history, with the First and Third Worlds involved in a major confrontation of cultures and the Third World and its myriad diasporas in the West engaged in an attempt to reframe their cultural identities to stave off the threat of “cultural genocide” through the effects of a rampant globalization (Rajagopal 2001). There are several entry points into online South Asian digital formations. Some of these points of entry privilege the cultural and social practices, whereas others privilege the economic routes. The several “routes” crisscross in layers. Neither the cultural nor the economic routes are mutually exclusive. The cultural entry point sometimes precedes the economic layer, and the economic quest for jobs tends to precede cultural transformations. These digital places and global networks become potential transitional places and contact zones for the formation of transnational subjects able to work within the increasing digital global economy through sociocultural processes facilitating the further intellectualization of labor (Bratich 2008; Naficy 2001).

What sorts of convergences, conjunctures, and connections emerge in relation to globalization and migrant populations the world over as we move into what is being referred to as “Web 2.0”? How are transnational, inter-generational diasporas manifested in relation to economic and cultural globalization? It can be argued that at the intersection of local and global markets, laboring locations and practices not only are impacted by international digital trade but contribute to the experiences that constitute digital diaspora. In his work concerning global economics, Venkataramana Gajjala explains that “ICTs [Information and Communication Technologies] enable hitherto untradeable services to be traded internationally, just like commodities, via the Internet and the telephone—recent outsourcing of software programming, airline revenue accounting, insurance claims and call centers to India ... have enabled not only small- and medium-sized firms but even start-ups to globalize their operations” (Gajjala 2006, 1).

The unbundling of goods and services for global dispersion through ICTs creates not only a transnational labor force but also a transitional space in which there is a sense of being betwixt and between “places” past and present in national and international domains. As a result, cultural identity narratives are enacted and represented simultaneously in the virtual and the real. And although transnational diasporas involving physical presence are affected and effected differently than those who labor in online spaces from “home,” both must negotiate unfamiliar cultural codes and scripts if participating beyond a local market. This impacts the present body in material ways regardless of location. In the process of compiling novel and nostalgic narratives and weaving them anew, liminal spaces in the process situate identity as seemingly anonymous, invisible, unknowable, and exploitable. No longer are labor markets within only the local reach of possibility and power.

Who has not known, at this moment, the surge of an overwhelming nostalgia for lost origins, for “times past”? And yet, this “return to the beginning” is like the imaginary in Lacan—it can neither be fulfilled nor requited, and hence is the beginning of the symbolic, of representation, the infinitely renewable source of desire, memory, myth, search, discovery—in short, the reservoir of our cinematic narratives. (Hall 1993, 236)

Stuart Hall notes how nostalgia and affect form the foundation for how we build narratives of identity and belonging, which he calls “cinematic narratives.” At online/offline intersections, we continually build “reservoirs” of mediated narrative and communicative spaces of diaspora. There are specific circumstances that compel us to mobilize the term “digital diaspora”—globalized markets, as well as the interactive nature of online technologies, notwithstanding—and these are not reasons enough to refer to digital travelers as digitally diasporic. We need to take into account the layered and nuanced ways in which such diasporic subjectivities are produced if we are to understand how the global/local continuum plays out in specific situations in present-day cultures and economies.

It can be argued that in the digital time-space continuum and our ability to record practices that leave behind histories and actual archives there is something unique because we can study the use of these technologies, thereby making it possible to view the resulting texts as diasporic in and of themselves. It can also be argued that in the formation of online representations (whether texts, moving images, static images, or three-dimensional representations) there is a certain situatedness. There is a sense of “landing” somewhere. There is a simultaneous affective reproduction of travel as well as a disorientation through encounters with other cultures that simulates culture shock. Thus, it can be argued that the quality of digital existence contributes to the use of the phrases “digital diaspora” and “virtual community.”

The term “digital diaspora,” however, is easily used to talk about how diasporic populations throughout the world use the Internet to connect to each other. Digital media used for digital diaspora formations are interactive and networked, potentially allowing people from all over the world to feel located in one “place” where people with similar interests and similar missions can gather in common space. Thus, online networks formed through digitally mediated communicative media—whether accessed via desktop computers, Xboxes, or iPhones—permit the local to exist within the global and vice versa. When print media became mass media, it allowed the imagining of common place through what Anderson (2006) called the convergence of capitalism, and print technology on the fatal diversity of human language created the possibility of a new form of imagined community, which in its basic morphology set the stage for the modern nation. Thus, print media’s accessibility—actually or potentially—to “the masses” went hand in hand with the growth of modern capitalism and internationalism as modern nations emerged.

Interactive online technologies go hand in hand with transnationalism based on global flows of capital and labor. The interactivity of the online technologies in current forms—as they are made available to “the masses”—is a logical extension for digital finance. The architects of digital capitalism have pursued one major objective: to develop an economy-wide network that can support an ever-growing range of intracorporate and intercorporate business processes. Anderson’s (2006) work has formed the basis of many arguments about digital diasporas and virtual communities, but few of the works that celebrate imagined community online make a clear political economy connection. Interactive digital and wireless technologies go hand in hand with transnationalism based on global flows of capital and labor. The interactivity of the online technologies in current forms—as it is made possible through “the World Wide Web”—is the logical extension for digital finance. In Dan Schiller’s words:

The architects of digital capitalism have pursued one major objective: to develop an economy-wide network that can support an ever-growing range of intra-corporate and inter-corporate business processes. This objective encompasses everything from production scheduling and product engineering to accounting, advertising, banking, and training. Only a network capable of flinging signals—including voices, images, videos, and data—to the far ends of the earth would be adequate to sustain this open-ended migration into electronic commerce. (Schiller 2000, 1)

The unique features and processes involving intra and inter exchanges, through multiple media that parallel with transnational business networks, are the backdrop against which digital diasporas form.

So we see very specific circumstances that allow a political-economic moment for mobilizing the notion of digital diaspora—which I must reiterate is not the same as “diaspora.” Globalized markets as well as the interactive nature of online technologies are unique features allowing this to happen. In such a context, we also need to take into account the layered and nuanced ways in which such diasporic subjectivities are produced if we are to understand how the global/local continuum plays out in specific situations in present-day cultures and economies. Although the physical material conditions of the digital user, consumer, or producer may not drastically change, it can be argued that there is something unique in the digital time-space continuum and in the ability to record practices that leave behind histories and actual archives. The resulting texts can themselves be viewed as diasporic agents/actors. It can also be argued that the formation of online representations includes a certain situatedness. There is a sense of landing someplace. There is a simultaneous affective reproduction of travel from place to place. There is also a sense of disorientation and displacement through encounters and placement in relation to other cultures that simulates culture shock. Thus, it can be argued that the quality of digital existence contributes to the use of the phrases “digital diaspora” and “virtual community.”

However, to understand how globalization and technology play out in transnational economies, we must take the argument further. We must attempt to understand the power hierarchies that permit the articulation of these online existences as digitally diasporic if we are to understand global and local placements and interlinked online/offline hierarchies.

Enactments and the realities that they produce do not automatically stay in place. Instead they are made, and remade. This means that they can, at least in principle, be remade in other ways.

JOHN LAW (2004, 143)

It is the tension between enactment and representation that produces the online (post-)human subject that leads to a spacio-temporal layering, slicing, splitting, and realigning of social, economic, cultural, and technical literacies that creates the impression of disembodiedness and placelessness. In actuality the body is being replaced, disembedded, and re-embedded in social and economic hierarchies suited to emerging digital capitalist organizations of labor and society through processes of experimentalism and creative destruction that characterize the neoliberal technocapitalist ethos embedded in present-day logics of globalization. It is in this technocapitalist-embedded environment that previous conceptions of humans as autonomous are challenged.

As bodies and digital identities converge in cyberspace and become re-embedded in the hierarchies of global capitalist economies, new platforms emerge for reconceptualizing the human as posthuman, no longer the exclusive entity responsible for processing and expressing information (Hayles 1999). Disseminating information, services, and goods internationally through interconnecting digital machines also links bodies, place, and temporal zones in ways that blur local/global cultural boundaries. Through this transitional space, multiple frames from which to view the interaction between humans and machines materialize at the intersection of online and offline culture and commerce. The cybernetic dynamic that exists between (post-)humans and machines works not to erase humanity but rather to decenter past perceptions that have placed humans as autonomous beings free to enact and exert agency and choice at will (Hayles 1999).

In cyber-nets, where cognitive systems are redistributed to include machine and human flesh, an actor’s identity and sense of self is formed in simultaneous feedback loops of re-enactment and re-presentation. The term “posthuman,” then, represents that shifting environment in which processes of becoming “human” occur at a time when “humans, animals and intelligent machines are more tightly bound together than ever in their cultural, social, biological and technological evolutions” (Hayles 2006, 159–166). What does this reevaluation of human in a post form mean for identity? If “post” means that we function as information systems, interconnected through digital channels and converging cultures, then “post” appears to represent identities in an ongoing state of flux and a constant process of renegotiating transitional spaces for a sense of physical presence.

The process of authentication of “Indianness” in online settings performs a Turing-test-type function as it forms the basis of inclusion and exclusion within online worlds and networks. This test is especially and clearly apparent in settings where the interactions are purely text-based (as in the pre-image-sharing world of online communication of the 1980s and early 1990s) or where the offline body of the user is clearly masked through the use of online avatars, as in the case of computer games and virtual worlds such as Second Life, where it is not customary for users to reveal their offline reality. Social formations in these spaces reproduce notions of “Indian” through online diasporic networks and are routed through renewed identifications and re-memberings as they actively, even intentionally, contribute to processes of transnationalization of labor and business through re-coded online and offline subjectivities. Verification of specific acknowledged “Indian” cultural literacies are often used in authentication rituals. Thus, byte-sized enactments, representations, and authentications of Indianness travel and flow through digital circuits, circulating and remixing into formations that articulate global identities.

On Second Life, the avatars and their profiles become identifiers of particular traveling cultural practices that are simultaneously situated within specific geographical locales as well as within global virtual-real markets. Thus, we view the crafting of avatar selves as situated practice—at radically varying contextual disjunctural and conjunctural online-offline intersections. The avatar is a technological artifact as is the apparel designed for it. Without the avatar, the sari on Second Life cannot exist. However, an avatar also exerts agency. The avatar forms an identity and takes on roles in the communities that it participates in. Without value in Linden dollars or in terms of contributing social and cultural meanings within at least some Second Life communities, the avatar identity will cease to exist.

How are identities expressed and agencies exerted in Second Life communities where sociocultural traditions and digital technologies overlap at the interface? Participating in online communities sometimes requires (re) situating literacies that gain acceptance and inclusion in unfamiliar cultural traditions. Performing identities through digitally created avatars also creates an ambiguous state in which the body at the computer keyboard is invisible and, hence, uncategorizable. In Second Life, an actor’s agency depends greatly on technical skill and cultural capital, a situation not altogether different from factors that influence exerting agency offline. Production and consumption of and within online networked communities, of course, are not dependent on physical presence, geographic locations, or time constraints associated with offline environments. When interacting in online spaces, the physical body is neither disembodied nor disembedded from the affective presence at the interface of human and machine. Indeed, a sense of belonging online is derived from identifying with places and groups that “feel” accepting, comfortable, homey, and, at times, familial and nostalgic. But personal affinities for particular people and places associated with past experiences are not the only factors that affect where and how bodies are positioned and identities are performed.

Writings about postcolonial diasporas and imagined community have been filled with discussions of nostalgic connections to the homeland. The notion that a simple linking of nostalgia for a past homeland locates the logic of diasporic emotional yearnings is problematic and nothing new to postcolonial, feminist, and other critical theories of diaspora and transnational travel. For instance, Jigna Desai (2003) has pointed out that formulations about diasporas that see nostalgia as the diasporic emotion that yearns for a past (manifested as a “homeland”) ignore the economic and political power relations and implications of diasporas. Further, it is clear from past work on South Asian diasporic identities that the politics of transnational mobility in any moment in history requires us to rescribe our identity in relation to the current political moment in racial politics. Thus, Avtar Brah (1996) notes that the referent “home” in two different questions (posed to her during an interview for a US education scholarship by an all-male US panel of interviewers) had two different meanings. One question invokes “home” in the form of a simultaneously floating and rooted signifier. “It is an invocation of narratives of the nation. In racialized or nationalist discourses this signifier can become the basis of claims ... that a group settled ‘in’ a place is not necessarily ‘of’ it.” The other question asked of her, she wrote, implied

an image of “home” as a site of everyday lived experience. It is a discourse of locality, the place where feelings are rooted ensue from the mundane and the unexpected of daily practice. Home here connotes our networks of family, kin, friends, colleagues and various other “significant others.” It signifies the social and psychic geography of space that is experienced in terms of a neighborhood or a hometown. That is, a community “imagined” in most part through daily encounter. This “home” is a place with which we remain intimate even in moments of alienation from it. It is a sense of “feeling at home.” (Brah 1996, 215)

In recent decades there has been a shift in how transnational business and media networks play out that highlights for us the fact that diasporas are not (and actually have never been) pulled together merely by a nostalgic pull back to one single “homeland.” The articulations of a nostalgia for such a “return” to a homeland miss the productive and re-membering nature of how nostalgia and the politics of affect play into emerging futures of diasporas. Here we intentionally spell it as “re-membering.” By doing so, we highlight the psychic acts of remembrance through individual and group memory as well as the social relations produced through the assertion of commonality in specific ways to increase the membership of such groups. This implies then that the re-membering of such diasporic communities happens through choice, selection, and recruitment, signaling active inclusions and exclusions in social relations based on the politics of what counts as correct emotion and nostalgia. Particularly, we focus on the emerging futures of diasporas that travel transnationally, carrying packaged and byte-sized “homes” as they re-articulate their sense of self and place themselves—and are in turn placed by others—as South Asians or Indians in diaspora. Avtar Brah asks, “What is the relationship between affect, psychic modalities, social relations, and politics?” (Brah 1996, 245; original emphasis). In this essay we signal toward such relationships in Indian digital diasporas.

In an interrogation of the Indian films in English that came out in late 1990s, such as Hyderabad Blues1 and Bombay Boys2, Jigna Desai has argued that the notion that “diasporas are ‘hailed by’ the narratives of the homeland nation-state that activate sentiments of nostalgia and belonging” is limiting (Desai 2003, 1). Pointing to the strong impact that South Asian diasporic populations have had on South Asian nation-states, she writes that “focusing only on the homeland nation as origin of culture, tradition, and values and the state as authority and granter of citizenship can overshadow an examination of the economic and political power in relations between diasporic communities and nation-states” (Desai 2003, 1). In her unpacking of how diaspora and the nation-state function dialectically to produce a transnational South Asian politics, she does not discount the use and function of emotion and affect in diasporic yearnings for return but instead suggests that the relationship between diasporic populations, the nation-state, and the articulation of “nostalgia” for a homeland is shaped through the politics of transnational capital and labor flows. Thus, she notes “that while diasporas hail the homeland through nostalgia and return, they do so when convenient. The homeland nation’s heralding of diaspora has little to do with the everyday lives and interests of the non-elite classes who are clearly critical of and ambivalent in regard to diaspora” (Desai 2003, 11).

Thus, although we cannot totally discount the role that nostalgia plays in how the home nation can mobilize, shape, and invoke the involvement of those in diaspora, we need to observe how the mutual influence functions through production and reproduction of tradition and culture in various contexts and how nostalgia then comes into play in these reproductions. As shown in previous literature on South Asian diasporas online, the “hailing” based in specific selective kinds of caste-based and religion-based nostalgias did produce certain kinds of community that exerted specific types of political influence in the “homeland.”3

Indian-identified offline bodies are building online socially networked Indian diasporas through such a placement of affect and through communicative labor. Technologically mediated diasporas occur at online/offline intersections. Community formations that emerge through their wired and networked portable digital devices help counter the sense of isolation and alienation faced by today’s youth as they continually uproot and replace locations in their mobile work and play lifestyles. In such mobile portable communities, affective links, manifested sometimes as “nostalgia,” are produced through re-membered pasts that are articulated through a placement of affect.

Divya Tolia-Kelly (2004, 314) writes about “locating processes of identity” through an examination of how everyday artifacts and individual objects relate to individual biographies but are simultaneously significant in stories of identity on national scales of citizenship and the intimate domestic scene left behind. The new site of home becomes the site of historical identification, and the materials of the domestic sphere are the points of signified enfranchisement with landscapes of belonging, tradition, and self-identity. Such enfranchisement is produced through a reconfiguring of memory and affect in processes of placing and locating people geographically, socially, and culturally through specific practices of authentication based in mediascapes and ethnoscapes that are crafted through seemingly scattered and gathered media in online and mobile transnational environments.

Particular South Asian cultural commonalities have also emerged through mass media and communication technologies since early 1960s in communicative spaces of diaspora. The recognition of these culturally representative images, texts, and sounds serve as remediations of an imagined community. Rituals of authentication emerge through expectations of recognition of these commonalities present in reproduced and remixed digitally mediated images, texts, and sounds within spaces of globalization. The reproduction and remixing occurs through a post-1990s “Bollywoodization” of South Asian–centric digital environments (Rajadhyaksha 2003, 25–39). These cultural formations are increasingly “Indianized” in a continuing synergy with satellite TV (the South Asian package), where themes such as Yeh Mera India (“This is My India”) are reiterated through a continuum commercialization, Bollywood films, music, TV serials, and Global TV–format-based productions such as Indian Idol, as well as advertisements for New York Life Insurance and so on (Punathambekar 2005, 151–175). Communities of online and offline bodies form around digitally mediated communicative practices often centered around the sharing of Bollywoodized media. They thus build pockets and enclaves of networked affect. The emergence of these seemingly disconnected yet representative cultural symbols in these spaces function to re-articulate emotional histories through replacement of affect in transitional place. Thus, these online networks transform from contact zones, where people from diverse backgrounds encounter each other, to transitional zones, where people build virtual commonalities and practices as they place themselves and enhance their skills in global work and play environments.

In the recent past, transnational traveling and diasporic South Asians have placed and transmitted affect audio-visually and sensually through radio, cinema, television, cassettes, video, and letters (and continue to do so). These traveling signifiers combine with physical objects—such as artifacts for living rooms, spices for “authentic” home food, fabric, and incense—carried along in suitcases and scattered memories to allow the South Asian diasporic to feel “at home” in various nooks and crannies of the globe. In the digital web 2.0 age, this packaging has come online in the form of hybrid “desi” popular cultures that leave behind spatiotemporally layered stains and traces of material artifacts in digital space. These are virtual objects that have been placed there by South Asians and those linked to South Asian culture and experience in some form. Such artifacts acquire multiple meanings through symbols and associations journeying through various networks. Thus, the use of remixed Bollywood tunes and digitally ethnic avatars mark South Asian digital diasporic place in virtual worlds such as, for instance, Second Life and Sims 2. Facebook and iPhone “apps” (applications) also code nostalgia and affect through circulating image and sound. Zynga, the makers of Farmville, reputedly the most widely played Facebook game in 2009, was compelled by Facebook-based “activism” (e.g., the campaigning of Indian-identified Farmville players through a Facebook group) to include the Indian flag as one the artifacts/objects to use in building one’s farm, and they also recently launched visual artifacts such as auto-rickshaws, monkeys, and elephants to signal the opening of a branch of Zynga in India.

Identities produced within digital contexts enabled by computer software and hardware are made possible through the coproduction of sociocultural digital place and global networks involving time-space compression. These sociocultural contexts are coproduced by inhabitants who access these contexts. The sociocultural literacies of these inhabitants determine the kinds of free labor they contribute toward the building of these spaces (Terranova 2000, 33–58). The continued inhabiting of these spaces leads to a reorganization of social space and everyday practice similar to that experience by call-center workers from India who are oriented to time zones and cultural practices in the Western worlds as described by Ananda Mitra (2008) in his work on outsourced call-center workers. Therefore, they experience a social, affective transformation that orients them toward life in global multicultural communities similar to those encountered by those in diaspora. But it must be noted that this social, affective transformation in and of itself does not automatically transform these sorts of digitally mobile travelers into members of the “diaspora.” The use of the term “digital diaspora” is not meant to imply that these people are part of the South Asian / Indian diaspora. The problematic and tricky nature of this usage itself signals the split of identity, performativity, and enactment in global environments of labor and leisure in today’s world.

The term “digital diaspora” is easily used to talk about how diasporic populations the world over use the Internet to connect to each other. Scholars such as Anna Everett and Jennifer Brinkerhoff (2009) have used the phrase in relation to specific situated histories of forced migrations (e.g., African American histories of slavery) and transnational travel, respectively. However, the link to labor flows and hierarchies of colonialisms and digital globalization is not always clear in the way this term is mobilized in general usage. In most general usage of the phrase “digital diaspora,” it is used to describe migrant populations without attention to the specific conditions of subjectivity that produce diasporas. Further, international NGOs (specifically, the United Nations) and transnational corporations as well as national businesses have mobilized the notion of digital diaspora in “reverse brain-drain” efforts where successful transnationals and migrants with money to invest actually get to return home (Gajjala, Rybas, and Altman 2008).4

The global/local binary that is used in conjunction with such uses of the notion of digital diaspora positions specific placed “locals” outside of a repeatedly unnamed global. However, as cultural geographers have pointed out, the separation of global and local into mutually discrete concepts is problematic. In this articulation and coupling of digital diaspora and global/local, it appears as though digital diasporas are what make us global, whereas the local is somewhere out there in “subaltern” space. This sort of articulation is not only “a denial of a fundamental ontological fact of our time: namely, that the global is in the local,” but it also ignores the fact that the global is made up of multiple locals (Castree 2004, 135).

So what is at stake in conceptualizing the users of online communication tools from various offline locations as “digital diasporas”? Various scholars have examined how terms such as “diaspora,” “postcolonial,” and “multiculturalism” tend to get deployed academically at a time when free-market ideologies need nations to open up to transnational flows of capital, consumer goods, and labor.

In mapping affective South Asian / Indian social networks online that emerge from the placement of affect as (im)material artifacts are produced in digital space, we suggest that memory, nostalgia, and affect simultaneously work to place and locate South Asian / Indian identifiers online. In doing so, we focus mainly on the circulation and proliferation of “Bollywood” media (whether as clips of music, video, image icons, or Second Life and Sims avatars), as well as on specific symbols and artifacts such as the sari. Many of these signifiers work in sync with a post-1990s opening of the Indian markets to transnational labor and trade as they reconfigure and “remix” older images and sounds for the techno-mediated “desi” global workforces that increasingly live in “digital diaspora” spaces and global-local offline hubs such as dance clubs and coffee houses as well as multinational corporate environments as they work and play. Thus, these groups of young men and women live in remixed and cross-routed communicative spaces of diaspora living partially in nostalgias from previous generations as they carve out futures containing a medley of sound-bites, icons, and visual loops that produce meaning and community identifications in nodal points and momentary (re)placements of skilling, re-skilling, and laboring.

The role of Bollywood-based music in these online and offline settings provides a link through the scattered visual signifiers as bodies and avatars sway in motion to sound clips coded digitally through online portals, offline loudspeakers, or iPods and smartphones. Nilanjana Bhattacharjya (2009) notes the shift in how Bollywood films are now funded since the economic liberalization of the Indian economy in the 1990s. She describes how the Indian government’s increased encouragement of privatization and international investment led to the Indian film industry increasingly being funded through contributions by non-resident Indian investors. This, in turn, led to a shift in the orientation of the films produced. More and more films were produced for the South Asian diasporic audiences. Ashish Rajadhyaksha (2003) refers to this process as the “Bollywoodization” of Indian cinema. On the other hand, Gregory Booth (2008) refers to this period as “New Bollywood” and notes the shift in the production technologies and processes for film and music in the Indian film industry shifted to privilege digital formats: “When younger, more technically sophisticated filmmakers and technicians finally introduced digital sound and filmmaking techniques and computers became widely available, a new era began that I call ‘New Bollywood’” (Booth 2008, 85). It is this transition in Indian Film—whether we call it a “Bollywoodization” or a transition to the “New Bollywood”—that allows the byte-sized packaging of images and sounds from the Indian film industry into South Asian digital diasporic spaces.

There are several transnational venues in the digital diaspora that are inhabited by iPod-carrying, smartphone using young men and women with their casual dress code and urban manners. Some of these spaces are less US-centric than the previous Internet-based South Asian generations. Social network systems and blogs (masked in semi-anonymity) blur notions of transnational sexuality as they hide behind Bollywood, Manga, and other pop icons and game-based avatars. There is a continuing play on gender and identity as the Bollywood icons produced in such communities are subjected to a gaze that blurs the boundary between heteronormative idolization of Bollywood stars and queer pleasure, also producing uncertainty about geographic location as they appear to multitask between work, fun, and offline/online formations of friends.

For this generation, being online is no more unusual than being on the phone, and individuals incessantly text message, tweet, and “FB” every mundane moment and download and exchange ringtones, pix, and flix. This group of young South Asians / Indians in digital diaspora are multiply literate and socioculturally flexible and mobile as they “hang out” in online communities of open-source developers, fan groups, and so on. This Indian digital diaspora is producing new layers of hierarchies and skills. Even as some of these youngsters seem just to be “hanging out” they are re-skilling themselves quite desperately in an attempt to outsmart the job market. At the same time, some other youngsters from more materially privileged backgrounds are indeed “hanging out” for leisure. The everyday practices of mobile generations in digital diasporas involve and invoke new and different kinds of problem-solving spaces from those inhabited by the materially underprivileged of the world.

In her article on “Henna and Hip Hop,” Sunaina Maira writes:

The youth subculture created by South Asian American youth in New York City is based on remix music that was first created by British-born Asian youth in the 1980s and that layers the beats of bhangra ... It mixes a particular reconstruction of South Asian music with American youth popular culture, allowing ideologies of cultural nostalgia to be expressed through the rituals of clubbing and dance music ... This remix subculture includes participants whose families originate from other countries of the sub-continent, such as Bangladesh and Pakistan, yet these events are often coded by insiders as the “Indian party scene” or “desi scene,” where the word “desi” signifies a pan–South Asian rubric that is increasingly emphasized in the second generation, and which literally means “of South Asia,” especially in the context of the diaspora. (Maira 2000, 240)

On Second Life are several dance clubs, where young men and women of South Asian descent and their non–South Asian friends “hang out.” At least, so it appears to the Second Life avatars who visit these clubs. Here Radhika’s descriptions and observations are based mostly on her experiences during the years 2007, 2008, and 2009.

I must make clear that my understanding of these encounters comes from a “deep hanging out” in various dancing clubs on Second Life to understand some apparently socio-technically scripted codes for behavior in such environments. Thus, I have visited dancing clubs that self-describe as Hispanic, Middle Eastern, Reggae, Jazz, “desi,” Bollywood focused, and so on.

I describe these environments based on specific visits that I made to a few Indian- and South Asian–themed dance clubs. In Second Life, no “place” stays static for long. Groups and individuals are continually rebuilding and relocating; therefore, the dance club experiences I discuss here can only be located in my affective experience and memory of the events and on snapshots and various YouTube videos taken by Second Life residents as they visit these clubs. (See the website http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y2w2p3v7WSE&feature=related to see how this scene looks.) However, merely viewing the video does not give us a sense of how it actually feels when immersed in the environment. Thus, my own readings of performative cues are what I rely on as I describe these clusters of activities.

All these dancing clubs have basic scripted objects—a dancing ball or a floor with dance scripts—to animate the avatars.5 They all have streaming media set up where the songs are streamed from a server (such as SHOUTcast or something else) onto the Second Life location. Most of them have tip balls or some form of money-collecting object and some also have exploding objects that are scripted to allow visitors to enter into a competition to win the jackpot by making a money contributions. Some clubs have themed dances and competitions for dancers to enter (this is also done through scripted objects), and fellow dancers can vote for the “best dressed female in pink” or another theme decided by the club owners.

In dance clubs focused on Indian interests, there is often a stock set of Bollywood remix music (and sometimes even video) streaming in. The Second Life avatars in these clubs are dressed in a variety of clothes but more and more of them (since 2007) are dressing in ethnic garb mostly modeled on Bollywood characters’ dresses.

In the dancing clubs with Bollywood music, Indianness is established mainly through familiarity with the music played and a basic minimum knowledge of Hindi, which is demonstrated in conversation among avatars in the club as they dance. “Where are you from?” is a question often asked of newcomers in an attempt to connect to a South Asian origin story. Bollywood is invoked as representative of India in such mediated environments but also serves as an apolitical and safe common language.

In 2007, I met a young lady (or so the avatar said she was) who told me she was on Second Life because she had heard of the available jobs there after seeing an advertisement in a regional vernacular newspaper in India. She started to type to me in a roman-script version of my mother tongue, saying she felt more “at home” on Second Life now that she had found someone who understood the same vernacular Indian language as the one she spoke everyday offline. When she told me where she was logging on, I was more than mildly surprised. The region was not remote or rural, but it was not one of the high-tech cities like Bangalore and Hyderabad or the more elite cosmopolitan cities like Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkatta, and Chennai. She had found a job on Second Life that would pay her the equivalent of about a dollar a week. She said that she was annoyed at all the male-type avatars that kept asking her for sex, which she considered silly and ridiculous. She wanted to learn all there was to learn about scripting and building in Second Life, and along the way she was making some interesting friends. She has visited many India-centric places and confessed to feeling uncomfortable in the dance clubs. She did not clearly say why. Certainly—if we are to believe the avatar’s story—this person behind the avatar was clearly in diasporic space through Second Life and not because she has physically traveled outside her home region. She was encountering versions of “America,” “China,” “the Netherlands,” and even “Australia” as she interviewed for jobs.

Some of these interviews were done through the voice feature on Second Life. The accents of the people behind the avatars came through to her, and that was her way of identifying where they were from, based on her knowledge of the geographic location of the accent (gleaned from exposure to other media such as television and film). Do I believe the story about this young lady I met on Second Life? And what are the truths I believe about her and why? Does the fact that she linked to my profile on orkut, where she has several friends from the region she claims to hail from and they all seem to think she is a young woman mean that she is real? What is “real” in this instance?

My experience and her experience are certainly real. That I chatted with someone who understands my mother tongue is real. That there was an advertisement in the regional paper the avatar mentioned is real. (I found a copy of the newspaper on the Internet, so it must be real.) The fact that she is working for Linden dollars in Second Life, building a shop, and designing saris and jewelry is real. So why should her stories about her offline life not be real? But that does not matter to the present articles and our understanding of digital diasporas in this framework. That the avatar has certain specialized knowledge of a specific geographic context and has language skills specific to a region attest to a certain kind of authenticity. S/he is a real Indian. Does it matter if she may be a he or that she may be someone who has recently traveled physically away from the region she claims to be from? Not for the understanding of digital diasporas within my framework for writing. But certainly it is of great importance that she is authentic in terms of Indian origin and that she is looking to make Linden-dollar money on Second Life. And it is also important and relevant that she has told me that Second Life is being advertised in various media in India, because this information can be verified.

What these truths about this Indian woman’s presence on Second Life point to is the economic pull of Second Life for young IT people living in India. This makes sense in relation to all the talk about crowdsourcing and outsourcing via Second Life. Businesses such as Wipro and IBM India have moved into Second Life to recruit and train. A visit to these areas reveals that they are fairly deserted at the moment, but the fact that these big companies have announced their presence on Second Life draws more young job-seeking Indians and other Asians into Second Life, thus changing the cultural, visual, and interactive climate within this three-dimensional reality.

As digital diasporas from these regions increase in size, the demographics and practices in Second Life will shift. Identifying, and identifying with, particular cultures or locations can be tricky in online spaces where anonymity is desired and identity deplored. For example, claiming an “authentic” identity online runs contrary to collective non-identities sought by the online hacker group Anonymous. Michael Wesch, in his contribution to this collection, explores how this seemingly faceless group conceptualizes identity as a “superficial struggle” that inevitably brings rejection, constraints, and exclusion from others based on set standards of naming oneself (in)correctly. Rather than viewing the self through nostalgic identity narratives, Anonymous offers freedom through a lack of identity, an uncertainty and ambiguity that opposes individualism and socially normed categories. Unlike other online communities where participants are perhaps curious and/or concerned with “true” identity, Anonymous abhors labels or markers that construct social hierarchies. The idea of obliterating identities in exchange for absolute anonymity reflects the multiple alternative choices for (non)identity play in online spaces. By recognizing the fluidity of identity and rejecting the notion of a fixed identity, we come to realize that “it is only through address that the body is brought into existence”; therefore, by refusing to address oneself as this or that, we are creating a “body impossible to interpellate” (Sunden 2003, 164) and thus impossible to appropriate. Reconceptualizing identity as an ongoing process that defies fixed categories and destabilizes traditional ways of identifying self and others provides an opportunity to explore various ways of becoming (in)visible in a variety of socially networked spaces. This is evidenced in Second Life, where people make visual contact with a representative avatar at the intersection of “real” and “virtual.”

In the online virtual world of Second Life, one of the ways in which participants attempt to identify themselves is in regard to location, yet their online presence indicates that they are “here” and “there,” simultaneously blurring “virtual” and “real” spaces. With the advent of audio capabilities, dialects are indicators of identity, but if a participant knows how to “speak” a particular vernacular, we still don’t really know, do we? Unlike Facebook, Twitter, and e-mail, which require identities to be “verified,” virtual worlds such as Second Life encourage playful exploration of identities by performing “self” through the participant’s representative avatar. Identifying someone’s status in this online space is generally evidenced as they negotiate new ways of performing through a digital device with particular codes required to navigate as well as interact socially through text and voice. Those more familiar with/in Second Life are recognizable by their more “polished” performances in regard to mobility and avatar appearances.

In the mid-1980s, when small businesses that previously offered typewriter tutorials began to provide computer training, I was compelled to sign up. As a housewife, freelance writer/amateur poet, and mother of a toddler who was fascinated with his mother’s typewriting, I sought to improve myself by going to computer tutorials. I learned early programs such as Word, BASIC, COBOL, and a smattering of Fortran. I have read books about artificial intelligence and “Eliza” (http://www.knowledgerush.com/kr/encyclopedia/ELIZA/) and hoped to have the computer spit out poetry for me as well. As I learned more about computers, the punch cards that I had often stumbled across in my brother’s strewed belongings when he came home for vacation from his IIT campus began acquiring historical significance to me. Later these punch cards acquired even more significance as I realized their similarity to the cards on the Jacquard loom as I began examining offline and online technologies in global/local contexts. Little did I know that in my search for magic and in my laziness, I was to stumble upon complex, nuanced intersections of science, technology, text, image, subjectivity, and gendered spaces of technocultures. I did not know it then, but the business that offered these tutorials was training the future offshore labor forces for transnational businesses.

Globalization in digital formats had arrived in my backyard in Bhopal, India, in the mid-1980s. Thinking historically, it is no surprise that the infamous Bhopal gas tragedy (in December 1984), resulting from manufacturing industries offshoring outmoded technologies to third-world urban spaces, signaled a transition into a different phase in globalization. The resulting globalization appeared more sanitized and benevolent, even as more manufacturing jobs and computer hardware factories continued to be moved into borderlands (maquiladoras) and other third-world regions, because this move was virtually invisible in the clamor of the digital. Thus, as audiences the world over watched the broadcast of this disaster and made meaning, protesting the transfer of outmoded technologies, the focus of communication scholars conveniently shifted to examining empowerment through information technology (IT).

Way back in the sixth grade, I was introduced to the world on the Internet by my sister. I used to frequent rediff.com chat rooms and used to select rooms like ‘teen love’ and ‘Calcutta cafe’ in the hope of meeting someone similar to me who would have compatible ‘a/s/l’s [age/sex/location]. I remember having multiple e-mail IDs and chat IDs through which I used to play pretend. Some chat rooms were eighteen and above and I used to pretend to be a college girl with a different location from mine. I was role playing, a different alternative identity. This went on till the tenth grade, and after that my sister again introduced me to orkut.com, a weird sort of website where I had to connect to people I already knew in real life; really, I thought to myself, nothing could be dumber that this concept, friending friends you are already friends with! But who knew? Orkut was getting me prepped and sensitized toward and for a bigger and better place: Facebook!

Older Generation: Youngsters these days are always on Facebook. They need to get a real life.

Younger Gen: I know she really went to Club Soho’s VIP lounge! She just put a picture right now on Facebook! Its really happening!

Chorus: What is real? Why is this real? What does this really mean?

Younger Gen: My mother is so embarrassing, she put up pictures of the Winter vacations and put it on “Public” View.

Older Gen: Isnt it wonderful that I can share my pictures with all the extended family members through Facebook?

Chorus: What is real? Why is this real? What does this really mean?

Younger Gen: My boyfriend proposed to me a week back, but his relationship status is still “single.”

Older Gen: I’ve closed off my FB account with my real name, I now have an alternate identity. My children and my spouse are not my friends.

Chorus: What is real? Why is this real? What does this really mean?

Younger Gen: So I decided to unfriend my mother today, but I couldn’t find her account anymore!

(She doesn’t find her mother’s Facebook identity anymore ...)

Chorus: What is real? Why is this real? What does this really mean? Can we locate our social networks?

What are the identities we acquire and what are the identities we lose, and why? Digital diasporas, as we see from the stories and examples described in this chapter, contribute to a transnational labor and management force necessary for the functioning of digital global economies. The functioning of such global economies rests on the coded interface that structures the practices in specific ways. Liberal discourse points to the rampant “multiculturalism” online as evidence of progress and democracy, but in coded fact this multiculturalism is almost accidental, shaped by a labor force that is based in a tiered hierarchy of layered literacies and material access.

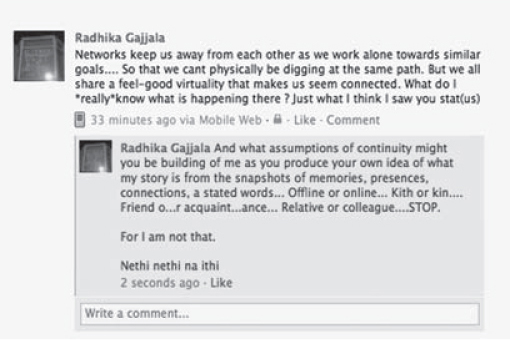

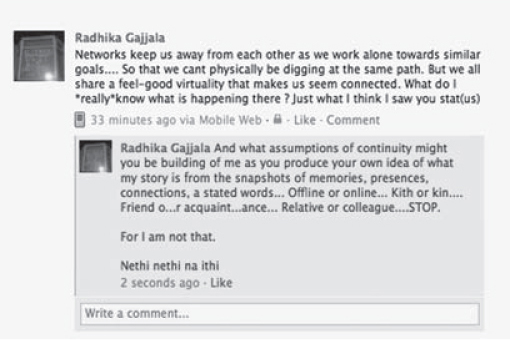

Identity production and technocultural agencies and subjectivities are shaped through the interplay of multiple offline and online contexts, histories, and literacies. Thus, as Mark Andrejevic (2009) notes, even the interactive interface provided by digital media reconstitutes public space in a manner that scatters the collective into individual scattered spaces. Networks, in fact, keep us away from each other as we work alone toward similar goals, so that we cannot physically be digging at the same path. But we do share a feel-good virtuality that makes us seem connected. The binary that then emerges begs the question, are you in my networks or are you in my everyday life; not, are you real or are you virtual. According to Hayles (1999, 156), “[t]his construction necessarily makes the subject into a cyborg, for the enacted and represented bodies are brought into conjunction through the technology that connects them.” What might this mean for continuing processes of globalization and the transnationalization of labor forces? Such questions need to engage the historical formations of transnational (“local” and “global”) communities of production in relation to specific contexts of technological design and use. Therefore, sociocultural descriptions of technological environments as well as their political and economic situatedness are essential to the study of transnational technological and digitally diasporic environments.

1. Hyderabad Blues, directed by Nagesh Kukunoor (1998; Stevenson Ranch, CA: Tapeworm, 2001), DVD.

2. Bombay Boys, directed by Kaizad Gustad (1998; Mumbai, India: Eros, 1998), NTSC.

3. See Deepika Bahri, “The Digital Diaspora: South Asians in the New Pax Electronica,” in Diaspora: Theories, Histories, Texts, ed. Makarand Paranjape (New Delhi: Indialog, 2001), 222–32; Amit S. Rai, “India On-line: Electronic Bulletin Boards and the Construction of a Diasporic Hindu Identity,” Diaspora 4, no.1 (1995): 31–57.

4. This situation is also problematic, but we will explore the details of mapping digital diaspora in this chapter. See work by scholars such as Lily Cho (2008) and Ella Shohat (2006) to understand some of the nuances of the concept “diaspora” in current times.

5. Kelly’s world blog (http://www.kgadams.net/2006/06/11/my-second-life-deflowering) describes scripted objects as follows: “Objects a user creates can have scripted behaviors—a table could have a fold out extension, or those ears I mentioned could wiggle. Even more intriguing, an object’s behavior could be based on something outside the game: virtual weather in an area could be based on real-world weather reports, for example—or a soccer ball could move based on telemetry from a real-world soccer ball.”

Anderson, B. 2006. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

Andrejevic, M. 2009. “Critical Media Studies 2.0: An Interactive Upgrade.” Interactions: Studies in Communication and Culture 1 (1): 35–51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1386/iscc.1.1.35_1.

Bhattacharjya, N. 2009. “Popular Hindi Film Song Sequences Set in the Indian Diaspora and the Negotiating of Indian Identity.” Asian Music 40 (1): 53–82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/amu.0.0012.

Booth, G. 2008. Behind the Curtain: Making Music in Mumbai’s Film Studios. New York: Oxford University Press.

Brah, A. 1996. Cartographies of Diaspora: Contesting Identities. London: Routledge.

Bratich, J.Z. 2008. “From Embedded to Machinic Intellectuals: Communication Studies and General Intellect.” Communication and Critical Studies 5 (5): 24–45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14791420701839163.

Castree, N. 2004. “Differential Geographies: Place, Indigenous Rights and ‘Local’ Resources.” Political Geography 23 (2): 133–67. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2003.09.010.

Cho, L. 2008. “Asian Canadian Futures, Diasporic Passages, and the Routes of Indenture.” Canadian Literature 199:181–201.

Desai, J. 2003. “Bombay Boys and Girls: The Gender and Sexual Politics and Transnationality in the New Indian Cinema in English.” Journal of South Asian Popular Culture 1 (1): 45–61. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1474668032000077113.

Everett, Anna, and Jennifer Brinkerhoff. 2009. Digital Diaspora: A Race for Cyberspace. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Gajjala, R., N. Rybas, and M. Altman. 2008. “Racing and Queering the Interface: Producing Global/Local Cyberselves.” Qualitative Inquiry 14 (7): 1110–33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077800408321723.

Gajjala, V. 2006. “The Role of Information and Communication Technologies in Enhancing Processes of Entrepreneurship and Globalization in Indian Software Companies.” Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries 26 (1): 1–20.

Hall, Stuart. 1993. “Culture, Community, Nation.” Cultural Studies 7 (3): 349–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09502389300490251.

Hayles, K. 1999. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hayles, K. 2006. “Unfinished Work: From Cyborg to Cognisphere.” Theory, Culture & Society 23 (7): 7–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0263276406069229.

Law, J. 2004. After Method: Mess in Social Science Research. London: Taylor & Francis. Kindle edition.

Maira, Sunaina. 2000. “Henna and Hip Hop: The Politics of Cultural Production and the Work of Cultural Studies.” Journal of Asian American Studies 3 (3): 329–69. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/jaas.2000.0038.

Mallapragada, M. 2000. “The Indian Diaspora in the USA and around the Web.” In Web Studies, ed. D. Gauntlett, 179–85. London: Arnold.

Mitra, A. 2008. “Working in Cybernetic Space: Diasporic Indian Call Center Workers in the Outsourced World.” In South Asian Technospaces, ed. Radhika Gajjala and Venkataramana Gajjala. New York: Peter Lang.

Naficy, H. 2001. An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Narayan, U. 1990. “The Project of Feminist Epistemology: Perspectives from a Non-western Feminist.” In Gender/Body/Knowledge, eds. A. M. Jaggar and Susan R. Bordo, 256–269. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Punathambekar, A. 2005. “Bollywood in the Indian-American Diaspora: Mediating a Transitive Logic of Cultural Citizenship.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 8 (2): 151–75. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1367877905052415.

Rajadhyaksha, A. 2003. “The ‘Bollywoodization’ of the Indian Cinema: Cultural Nationalism in a Global Arena.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 4 (1): 25–39. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1464937032000060195.

Rajagopal, A. 2001. Politics after Television: Hindu Nationalism and the Reshaping of the Public in India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511489051

Sassen, S. 2004. “Local Actors in Global Politics.” Current Sociology 52 (4): 649–70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0011392104043495.

Schiller, D. 2000. Digital Capitalism: Networking the Global Market System. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Shohat, E. 2006. “Travelling ‘Postcolonial’ Allegories of Zion, Palestine, and Exile.” Third Text 20 (3–4): 287–91.

Sunden, J. 2003. Material Virtualities: Approaching Online Textual Embodiment. New York: Peter Lang.

Terranova, T. 2000. “Free Labor: Producing Culture for the Digital Economy.” Social Text 18 (2): 33–58. http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/01642472-18-2_63-33.

Terranova, T. 2004. Network Culture: Politics for the Information Age. London: Pluto Press.

Tolia-Kelly, D. 2004. “Locating Processes of Identification: Studying the Precipitates of Re-Memory through Artefacts in the British Asian Home.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 29 (3): 314–29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.0020-2754.2004.00303.x.