CHAPTER TWO

FROM STEEPLES TO SNAPCHAT

The Darwinian March of Media

THE TERM “social organism” was coined by the nineteenth-century French sociologist Émile Durkheim, who viewed society as a living being whose health was determined by how well the core realms of economics, politics, and culture interacted with each other. Much more recently, the concept was taken on by the biologist/anthropologist David Sloan Wilson in Darwin’s Cathedral, a groundbreaking book on religion’s role in the evolution of societies and civilizations. If we conceive of societies as organisms, Wilson argues, religion can be viewed as a vital agent of prosocial behaviors that put common interests ahead of those of the individual. In this way, religion—which he describes as one kind of “adaptive belief system”—has been key to the survival, growth, and prosperity of communities. From stories of capricious gods that discouraged people in ancient civilizations from breaking their societies’ defined order, or the Hindu water temple rituals that simultaneously helped Balinese society coordinate an orderly irrigation system for its rice paddies, religious practices had a unifying effect on communities. They helped societies evolve into bonded, networked communities and thus advance their computational capacity.

Until the Renaissance spurred a surge of scientific inquiry that ultimately led to the Enlightenment and the modern world, dogmatic religious ideas were the main glue bonding people together. These ideas were delivered in the form of myths and memes, stories packaged into a familiar narrative structure. The consistency of the stories’ patterns and tropes—evident in how mainstream religions share strikingly similar genesis myths—ensured people could absorb them and, ultimately, act upon them.

This reflects a key point in the formation of knowledge: that cognitive skill depends on a capacity to recognize patterns. An idea simply can’t take hold if there is no preceding, related idea for it to latch on to, if it is utterly unfamiliar. Until the theories of Copernicus, Galileo, Darwin, and others were burnished with the weight of scholarly curiosity and empiricism and became more widely accepted, people’s pattern recognition capacity was constrained. Their in-built “computers” simply hadn’t evolved to where they could comprehend and absorb the patterns in the data they were receiving. Gravity, the laws of physics, meteorology, immunology—none of these ideas existed, which meant people didn’t have the foundations with which to understand the most simple of wonders.

In this environment, religious myths flourished; they were the means through which to influence the public mind. The stories told by priests represented idealized packets of conceptualization—they were memes, those basic building blocks through which ideas are passed on and which we’ll explore in greater depth in chapter 4. And for their purpose, they were highly effective: Notwithstanding history’s many episodes of internecine bloodletting, they mostly kept societies bonded. And yet this seemingly robust system’s days were limited. Eventually, with the aid of new communication technologies such as the printing press, as well as the literacy ushered in by middle-class education, societies’ capacity for sharing and processing information expanded. This meant that more scientifically founded ideas could be absorbed. Human culture evolved.

Before we delve into how the Social Organism broke free of religion’s domination in the realm of ideas, I think it’s useful to take a walk down history lane and look back at the early Catholic Church through the lens of mass communication. As a kid I mostly associated the Catholic Church with the domineering presence of the largest building in my hometown of Clarksdale, Mississippi. But in one of the many a-ha moments after my revelation at Joshua Tree, I came to view the Church as one of the world’s earliest and most successful broadcast networks. Its bell-ringing steeples were like television towers, calling the masses to tune into the Word of God. The bell would ring at eight a.m. The congregants would gather to hear the incontrovertible truths and dogma in the building filled with religious, memetic iconography. Its priests were like TV anchors, the only individuals in touch with God and thus empowered to disseminate the Word. In the pre-Enlightenment Church, that was because parish priests were typically the only literate person in a village and because there was only ever a limited supply of handwritten Bibles to go around. Priests delivered a single Rome-sanctioned message, just as big news organizations hew to common rules on language style, news values, branding, and, to varying degrees, the media company’s editorial line.

As a conveyer of ideas, the Church was genius. It truly grasped the power of imagery. Everything from the priest’s gold-laced vestments to his elevated position in the pulpit reinforced papal power, while the iconography of Christianity gave us our most lasting memes. “Grumpy Cat” photos, the Obama “Hope” poster, and the Guy Fawkes masks of Anonymous have nothing on the crucifix, the Christian fish, or the Virgin. These images were replicated and repeated through the centuries, artists tweaking and reinterpreting the meme but staying true to a core message. Although sanctioned artists participated in this vast process of message management, most of the Church’s lay community had little capacity to contribute their own content. And for centuries they had no way to safely challenge the dogma. All of this formed part of a mass communication architecture that was, for centuries, all but impossible to surpass.

Then along came Johannes Gutenberg. The first book he published with his new invention was the Bible—a wise choice, given that its themes were utterly consistent with the pattern recognition capabilities of the widest audience. But the printing press unleashed something that would ultimately expand people’s access to powerful ideas very different from those laid down by Rome. It created the possibility of more widespread and rapid dissemination of information, chipping away at the timing and distance limitations of conversational communication, which demanded immediacy and proximity. Along with other sweeping societal developments—including advances in literacy from the introduction of private and, eventually, public education—the printing press broke the class structure that the Church had forged. It laid the path to a middle class, a new educated group open to alternative ideas about how to organize society and comprehend the world. And to service their need for such ideas, another powerful idea sprung forth, one that harnessed the vast new publishing power unleashed by Gutenberg: mass media. Ironically, the early literature that emerged at this time was based on the secular delights of consumption, sex, and comedy—a pattern to be repeated with the early Internet.

This new phase in the evolutionary march of society’s communication architecture helped to craft a secular model for sharing information, one freed from the singular dogma of the Church. As a growing literate population demanded information that was independently delivered, a new breed of writers and editors arose: journalists. Inspired by the liberal philosophies of Voltaire, Montesquieu, Locke, and John Stuart Mill, they offered fresh descriptions and explanations of politics and culture without care for whether they complied with the worldview of authorities. And after the mid-nineteenth century, when media organizations figured out they could fund their operations by selling advertising slots to producers that were trying to reach a growing market of middle-class consumers, news organizations grew in size and influence, with on-staff writers covering an ever-wider array of topics or “beats.” These publications grew in great number in Britain as the industrial revolution took hold. In the United States, newspapers sprung up everywhere in the nineteenth century. While their approaches encompassed a wide range of political philosophies and ethics, in general the industry embodied the Jeffersonian principles of free men, free property, and free ideas.

In the twentieth century, new systems for capturing and distributing information brought the media industry into another evolutionary phase. Photography, wireless, moving pictures, broadcast television, and later cable TV all offered new tools to deliver messages and spread ideas to the public more efficiently and widely. These technologies—the newspaper, the magazine, the book, and radio and television—shaped Western culture through the twentieth century; they sat at the centers of people’s lives. When Americans listened to their president on the radio or watched Walter Cronkite on CBS tell them “the way it is,” bonds were forged across an imagined, coast-to-coast community of co-participating citizens. Broadcast media was as much of a nation-building force as any technology before it. With no Church and no government dictating the terms, media businesses became powerful shapers of public thought. This could happen in blatant but also subtle ways, such as when TV voice modulation led the Mid-Atlantic accent to earn unofficial authority status—by default, diminishing the authority of, say, a Mississippi drawl like mine.

Yet, despite its universal reach, mass media was still very much a club. While many media business owners avoided interfering with the work of their journalists or at least paid lip service to the principles of balanced reporting, there was no getting away from the centralized power that these institutions wielded. Editorial boards and broadcast producers were gatekeepers of news. They got to decide what the public learned about and what it didn’t. They defined the so-called “Overton window,” a term based on Joseph P. Overton’s idea that there is only a narrow range of ideas that politicians considered politically acceptable for them to embrace. These institutions’ centralized control over “messaging” meant that close relationships were forged between those who made news and those who wrote it. Imagine now, in this more open era of social media, White House journalists agreeing to keep Franklin D. Roosevelt’s disability out of their reporting or ignoring John F. Kennedy’s sexual adventures because it wasn’t in the “public interest.” Whether we were better off because of those decisions, competition would make it impossible to uphold them now.

With social media, this industry has made a giant new evolutionary leap, one that I think will have as profound an impact on society as Gutenberg’s printing press. Again, we are not arguing that the evolution of social media must create indisputably positive benefits. I’ll say it again: Evolution is not the same as progress. What we are saying is that social media represents a more evolved state for society’s mass communication architecture. And there is no turning back. The evolutionary algorithm has brought us to the Social Organism, within which we are now linked in a giant, horizontally distributed network. It has armed us with a far higher level of computational capacity than ever before, capable of generating, replicating, and interpreting ideas more rapidly and of spreading them more widely.

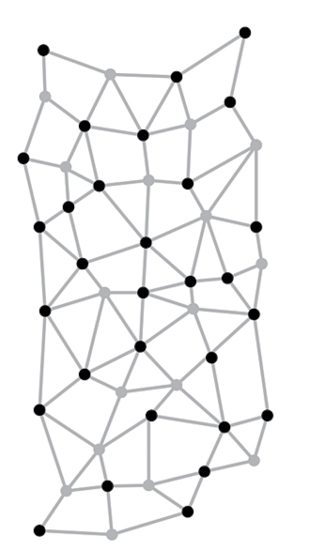

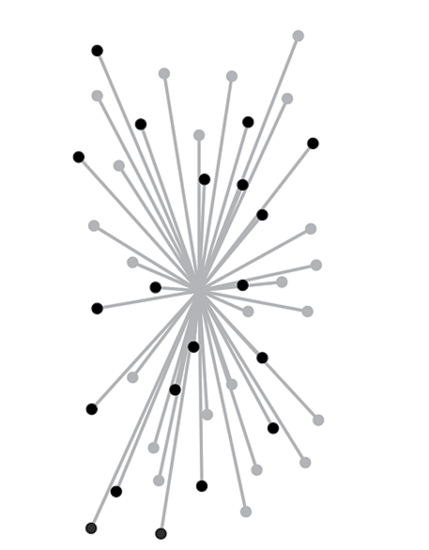

Donald Davies, Vint Cerf, and Bob Kahn are frequently referred to as the “fathers of the Internet.” But it’s fair to say that the Internet’s grandfather is a guy called Paul Baran, who in the late 1950s came up with something he called “distributed adaptive message block switching.” You might not have heard of Baran, but perhaps you’ve seen his oft-cited drawings of different network structures:

Centralized

Decentralized

Distributed

The first model represents the kind of communications relationships that has underpinned many forms of human organizations throughout history. In particular, centralization describes the telecommunications systems that persisted in most countries before the Internet era, where all traffic had to pass through a national telephone company’s central hub. The second shows a system of interlinked hubs-and-spokes relationships in which various centers of coordination function as nodes within a wider, ad hoc system. It, too, is pervasive: The hardware and commercial structure of the Internet, formed around an array of different ISPs servicing multiple customers, could be described in this way. But Baran was more concerned with how information flowed, not so much how users physically connected their computers to the network or paid for access. And for that he conceived of the third model, a distributed system.

Distributed networks now pervade our communication architecture. In fact, this flat, center-less, distributed structure is the framework from which social media derives its remarkable power. Baran, who worked on U.S. Department of Defense–funded projects at the RAND Corporation during the Cold War, proposed this structure not to enhance information flow per se but because it would be more secure. The idea was that if a node went down due to attack or malfunction, it wouldn’t bring down the whole network as would happen in models where everything flows through a central hub or hubs. Baran knew the structure could not be achieved without a reimagining of how we package information itself. In the distributed structure, data had to be broken into blocks that multiple nodes could simultaneously read. As it turned out, this was a bigger breakthrough than the security improvement it promised; this new system overcame the two ever-present constraints on human communications: time and distance. It would lead to the Big Bang of the Internet age, a massive breakup in the pre-existing order of the communications universe. From it we got an explosion in innovation and in new online life forms that were previously unimaginable.

Baran’s idea, which he called “hot-potato routing,” was at that time too unconventional for the U.S. telecommunications network, at whose center sat the all-powerful AT&T Corp.’s Bell System. That system comprised a series of hubs connecting local and long-distance telephone lines. Coordinated by switchboards, the hubs would enable point-to-point communication between two telephones, based on the codes in each phone’s number. The model’s legacy persists today in the NPA-NXX telephone number format of +1 (xxx) xxx-xxxx, which contains the country number, the three-digit area code, the three-digit prefix for the local region, and finally the four digits of the line owner. The model assumed a dependence on geography that Baran’s idea made redundant.

A decade later in the late 1960s, the Welsh computer scientist Davies recognized that Baran’s model could dramatically boost the amount of information passing over a network. “Packet switching”—the term Davies chose, somewhat less colorful than Baran’s—meant that information no longer traveled point-to-point, where it would get trapped in bottlenecks. Data could now be delivered, regardless of whether there was a “busy signal” on the relevant line. Davies incorporated a version of Baran’s technology into an internal communications network run by the United Kingdom’s National Physical Laboratory, and, in meetings with Americans working on a Defense Department contract to build something called the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network, he convinced them to employ the same approach. In 1969 the ARPANET was launched on a packet-switching model. Four years later, Cerf and Kahn perfected two instructional protocols for managing those packet flows: the Transmission Control Protocol and the Internet Protocol, typically lumped together as TCP/IP. This system would allow virtually any other network to link to the ARPANET. The concept of the Internet was born at this moment.

With the Internet infrastructure in place, the evolution of social media could begin. While they didn’t carry the label “social media,” the phenomenon really began with email and instant messaging, which made sending a letter redundant and drastically cut the time for text-based communication. Then, with online mailing lists and Usenet groups organized around “threads” of conversation, a social dimension was added: Rather than one-to-one communication, these innovations allowed for one-to-many message dumps. Volunteer-run bulletin board systems, or BBS, emerged in which people with an interest in certain topics could not only share ideas but also download communal, independently created software code. These forums were popular but they required commitments from tech-savvy coordinators to stay running.

The biggest breakthrough was arguably that of British engineer Tim Berners-Lee, who in 1989 invented the World Wide Web. Building on the idea of hypertext, a term coined in 1963 by information technology philosopher Ted Nelson, Berners-Lee devised the hyperText markup language (HTML), a computing language for creating online documents that formed links over a network via special pieces of embedded code. By clicking on those code pieces, readers could jump from one document to another, “surfing” over a web of interlinked “web sites” of potentially unlimited size. It then took the 1993 release of Marc Andreessen’s Mosaic browser, the precursor to the mass-marketed version known as Netscape, to bring Berners-Lee’s brilliant idea to life. The Netscape browser introduced hundreds of millions to the World Wide Web with its colorful, easily navigable websites. This in turn unleashed a desire for many of them to publish their own sites, for which they now simply needed basic HTML programming skills or to acquire the services of someone who did. In time, these sites would provide the primary means of human online interaction and the foundation for the twenty-first-century version of social media.

Another formative milestone in the development of distributed communications architecture came with the Telecom Act of 1996. By mandating that Internet access would be open and economically unregulated, it unleashed rapid evolution in the digital ecosystem. Packet-switching communication over the Internet protocol now existed in a government-enforced environment of open innovation, which meant that geography and time were fully rendered irrelevant for all American participants in communications. That spurred the invention of all manner of applications to drive down the cost of publishing and consuming information.

Because they democratized access to modes of communication, these reforms encouraged the users of them to seek out ever-wider networks of engagement; the idea of “network effects” became the defining economic model for the industry. Now, you can’t just order up a network; success depended on organic growth. By extension, that meant that the organizational structure and development of the systems and platforms that underpinned this expansive industry began to follow patterns seen in the natural, biological world. Whether or not it was part of a deliberate strategy, biomimicry found its way into Silicon Valley’s organizational DNA.

Unlike the command-and-control structure of vertically organized human corporations, no single authority orders a colony of termites to work together, dictates how proteins and other molecules should interact within your cells, or orders a mushroom to grow. The constituent parts in an organic organization are autonomous. It’s an apt descriptor of how individuals within a distributed communications network function together. This horizontal, autonomous, and organic system would become even more relevant once the invention of blogs gave rise to a new form of citizen journalism and even more so once social media messaging platforms gave the idea of the “public voice” a new, organic distribution system. From that emerged the Social Organism as we now know it.

Before we go there, we must reflect on the economics of the IT industry, which were driven throughout this period by the laws of physics and mathematics. In particular, a powerful combination of what became known as Moore’s and Metcalfe’s laws was unleashed. Former Intel CEO Gordon Moore’s idea—by now an article of faith in Silicon Valley—states that computational capacity, measured by the number of transistors that can fit on a microchip, doubles every two years. Ethernet co-inventor Robert Metcalfe’s law states that the value of a network is equal to the square of the number of nodes. Because of the perpetual pressure from these mathematical growth functions, the cost of publishing and accessing information on the Internet kept falling as computer storage, Web hosting, online bandwidth, and access speeds became ever-more efficient. And as the infrastructure improved from painfully slow dial-up modems to the near-instantaneous broadband connections of today, so, too, did the ability to search the Net. Search engines went from the early cataloging and query functions of AltaVista and Yahoo! to Google’s all-powerful algorithm.

The audience grew exponentially along with the technology, which greatly enhanced the potential economic impact from publishing information online. A powerful feedback loop of technological improvement and network effects took hold as more and more people logged on to access ever richer content and then in turn fed more content back to the emerging Social Organism. Soon websites became interactive, allowing readers to engage with them via comments or by posting in specially designed public chat rooms and forums. It was a new paradigm: People were sharing their thoughts with the world at large without requiring the authorization of a publishing gatekeeper.

The defining content vehicle of this new age was, initially at least, that of the weblog—or blog, as we now call it. Using dynamic websites, writers would provide anyone who’d listen with a chronological stream of updates on their lives and thoughts. The concept soon morphed into a kind of would-be journalism—although most bloggers were more like op-ed columnists. With the release of the Rich Site Summary, or RSS, feed format, an entire industry of citizen journalism was spawned around low-cost, user-friendly publishing services such as Wordpress and Google’s Blogger. With more lured by Google Ads’ promise to micro-monetize their content, swarms of bloggers descended onto the Internet.

To this day, the vast bulk of blog posts are just floating in the ether, crying out for someone—anyone!—to read them. And yet a big enough cadre of super-bloggers amassed such followings that they singlehandedly shook up the traditional media model—trailblazers like video game expert Justin Hall, political blog pioneer Andrew Sullivan, and gossip mavens like Mario Armando Lavandeira Jr., aka Perez Hilton. They were unhinged from the traditional journalism rules of style and ethics, employing a free form of expression to which readers gravitated. All of this posed a major challenge for established news organizations, which now faced stiffer competition for the limited resource of reader attention span and the corresponding advertising dollars. With these declining revenues they struggled to afford the high cost of gathering the news that, somewhat unfairly, the bloggers got to read, recycle, and comment on for free.

Many decided to fight fire with fire, carving out space on their websites for in-house blogs staffed by writers who opined in a more colorful style. But as independent blog empires such as the Huffington Post and Gawker emerged, the labor and distribution costs on traditional newspapers became almost too much to bear. Newspaper journalists were forced to do more with less: writing for both print and online, providing accompanying blog posts, and doing online TV spots. The time for deep, quality journalism shrank. Layoffs grew, bureaus were shut down, print editions were canceled, and many newspapers simply perished. Despite the online advertising industry’s promise of a revolution in smarter, more targeted ads, the overwhelming competition for “eyeballs” dramatically drove down “cost per impression” (CPM), the metric used to price ads. The same effect came from the measurement of click-through rates, which strengthened advertisers’ bargaining power by demonstrating how effective or otherwise each media outlet’s reach was. More competition and more transparency—newspapers were hit with two most powerful deflationary forces in a market economy.

All of this plays out in some striking numbers: From Ian Ring’s first online e-journal in 1997, the number of blogs soared to 182.5 million by 2011, according to NM Incite. Now, with Tumblr alone claiming 277.9 million blogs, the true total is far greater. Meanwhile, newspaper revenues are less than half what they were ten years ago and the number of newsroom employees in the United States has dropped to below 36,700 from 56,400 in 2000. This is what extinction looks like when our communication architecture undergoes rapid evolution.

It was the bloggers’ content that disrupted the old media order, but it was the new Internet-based technologies that gave them the means to do so—much as Gutenberg’s printing press gave Renaissance thinkers the tool they needed to challenge the old feudal order. And at the turn of the millennium, another new innovation in the distribution of content would arguably make an even bigger impact on our mass communication system, giving even greater opportunity to those outside the establishment to make their voice heard. With the arrival of social media platforms, the Social Organism finally had the distribution system it needed to start defining the shape of our increasingly digital society.

The rise of social media platforms created a vibrant market that locked publishers into an even more aggressive competition for audience attention. In permitting people to share any piece of communication in a collective, communal way, this new architecture took us from the twentieth century’s centrally managed mass media system to a social system founded on virtual communities. It meant that the machinery that carried the message was no longer defined by printing presses and television towers but by the neurons and synapses fired by emotional triggers in billions of digitally interconnected brains. Information distribution was now about biochemistry, psychology, and sociology.

The new model depended on the organic growth of online networks, which leveraged people’s personal connections to build ever-wider circles of connectivity. These interlinking human bonds became the metabolic pathways along which the Social Organism’s evolving communications channels would form. It meant that the most lucrative business in publishing shifted from producing content—since everyone could now do that at much less cost—to facilitating publication, primarily by expanding social networks via dedicated platforms. In a sense, these platforms—with which entrepreneurs like Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg and Twitter’s Jack Dorsey would eventually build highly successful business models—were like cable TV services, although their “equipment” was composed of human relationships rather than coaxial cables.

Encouraging ever-wider webs of human interconnection became the MO of any social media platform company. As per Metcalfe’s law, the bigger the network, the more information would travel over the platform, from which revenues could be extracted in fees for advertising and data analytics. This spawned an intense burst of innovation and competition among wannabe platforms. All breakthrough innovations that lead to paradigm shifts tend to create a fluid marketplace of start-ups and flameouts, but in this case the cycle of creation and extinction was very short indeed. For our purposes, that’s useful, because we can learn a lot about what makes the Social Organism grow by looking at the rise and fall of early models.

One of the earliest social media sites was SixDegrees.com, founded in 1997. It was named for the notion—popularized through the parlor game “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon”—that all human beings are connected to each other by no more than six degrees of connection. (Incidentally, a recent Facebook study has found that everyone on that platform is now an average of only 3.5 degrees separated from each other; social media truly has made the world smaller.) Six Degrees users would list their acquaintances and, as it grew, could post messages and bulletin board items to people in their first, second, and third degrees of connection. The company swelled to one hundred employees servicing around 3 million users and was sold to college campus media and advertising company YouthStream Networks for $120 million in 1999. But in 2001, Six Degrees fell victim to the bursting of the dot-com bubble, as the gold rush–like mania that had unquestionably poured money into Internet companies with the flimsiest of business models turned into the exact opposite: a rush for the exits. Whether Six Degrees was worthy of the same newfound cynicism, the end of the gravy train of money meant the end of its business. YouthStream itself was forced to sell the following year for a measly $7 million.

It wasn’t just the dot-com bubble that doomed Six Degrees. It was also confined by the limits of the dial-up modem and by a BBS structure. As discussed above, these bulletin-board systems required the time-consuming involvement of tech-savvy moderators. All of this meant that the entire premise appealed mostly to geeks. It took Friendster, which launched in 2002, to take social media mainstream. Much as Facebook would do later, Friendster allowed users to invite their contacts to join a network on which to share online content and media. In just three months, the site had amassed 3 million users, many using it for online dating and for discussing hobbies. Within a year, Google had offered Friendster’s founder, Jonathan Abrams, $30 million for the site. He rejected it, partly because various Silicon Valley advisers told him he had an opportunity to turn Friendster into another Yahoo! worth billions. It was a fateful decision. Shortly afterward, Friendster also lost momentum, surpassed by another newcomer, Myspace.

There’s been much business school ink spilled on Friendster’s failure, and it tends to focus on the deal-making obsessions of Silicon Valley. But in essence it comes down to how well it competed for user participation, and some of its policies were antithetical to the Social Organism’s growth demands. I remember visiting Friendster’s offices to find staff members deleting all the Jesus avatars. Why? I asked. “Because they are not real; they can’t fuck,” came the colorful explanation from Abrams. He wanted to limit Friendster to identifiable people, which meant excluding anonymous avatars. This dogma opened up an opportunity for a more laissez-faire competitor. Myspace, which allowed thousands of artists and other users to create inanimate profiles, helped to build an important new model for sharing music, including direct-to-consumer music releases, social fan clubs, and efficient ticket sales. By curbing the creativity and self-expression of its many users, Friendster had hindered its own distribution network.

The Friendster-versus-Myspace story confirms an amalgam of at least three rules in our playbook from the seven characteristics of life that we introduced in the Introduction and which we will discuss in other parts of the book.* In order to grow, maintain homeostasis, and adapt to survive in the event of a change in the environment (in this case, the arrival of a competitor, Myspace), content delivery systems need to keep the Social Organism’s metabolism nourished and its pathways of communication open. Curtailing creativity works against that goal.

So what about Myspace? It was also launched in 2002, but really took off in 2003 and 2004, soon attracting, and accepting, a whopping $580 million offer from News Corp. By 2008, the service peaked at 75.9 million monthly unique visitors, pulling in as much as $800 million a year in classified ad revenues. But shortly after that, the site began to decline. The reason? It comes down to the incompatibility of a giant corporation’s proprietary instincts with a free-content system that requires organic network expansion.

Here, too, I have personal experience. In 2006, News Corp. began to shut off non-proprietary applications from the Myspace platform: which meant, for example, that the revenue-sharing video content site that I’d created, Revver, could no longer distribute videos over the Myspace network. I took the view—and of course continue to—that the addition of any new exciting content would have widened Myspace’s user base, to the firm’s advantage. But News Corp., like so many old-economy companies, takes a very proprietorial view of content, subjecting decisions about it to lawyers and committees that worry about the projection of the corporate brand. Back then, such companies’ instincts were to reject arrangements that didn’t give them ownership of the content (even if that material was not produced by anyone on payroll, as was the case with the bulk of Myspace’s content-providing users). The upshot was that when a Myspace user typed in “revver.com,” they would just see an ellipsis: “...” More important, this act of curtailing content expansion went against the interests of the Social Organism’s organic growth.

When News Corp. imposed its draconian rules, Myspace was left with all the gaudy mishmash of personal ads hailing from its laissez-faire roots but none of the innovative verve that should have cemented its status as a vibrant forum for artistic creation—the worst of both worlds, in other words. This failure opened the door for Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook to claim the crown as king of social media. In 2011, News Corp. sold Myspace to a group of investors that included singer/actor Justin Timberlake (who, ironically, played the part of my former business partner Sean Parker in a film about Facebook, The Social Network). The deal came in at $35 million, more or less the same puny sum that Google had offered to Abrams for Friendster.

Once broadband connections took hold—and later, streaming technology—video became the next big social media battleground. In that one, I played a direct part via Revver. We realized—as did the three former PayPal employees who founded YouTube—that you needed a separate site to host people’s videos, since private websites usually couldn’t handle the bandwidth. But what I’m most proud of is that we pioneered the idea of revenue-sharing, setting a standard for paying providers a portion of the advertising revenue that their work generated. We saw it as a way to encourage good content. The idea won us some innovation awards early on. Still, in the end it was YouTube, which Google acquired in 2006, that became the dominant platform for video. YouTube soon started rewarding people for revenue-generating content, too, and its model has since become a critical source of revenue for filmmakers and musicians. Google has done a good job developing tools that allow artists to register their works under YouTube’s Content ID system, which seeks to ensure that all copies of their work are covered. However, a lot of stuff slips through, meaning that rightful owners aren’t properly compensated and the calculation of revenues and how they are distributed is less than transparent. Start-ups such as Los Angeles–based Stem are working on bringing transparency to this space. The next step, I believe—not only for music and videos, but for all art—is a truly decentralized system in which artists, and only artists, have a say over who sees their work and how they get paid. Blockchain technology, which we’ll discuss in chapter 8, could help to bring us there.

This brings us to Facebook, which since its launch in 2004 has swelled its user base to a mind-numbing 1.5 billion. The Social Network did a number on CEO Mark Zuckerberg, painting him as an uber-ambitious control freak who will stop at nothing to get what he wants. I don’t know Zuckerberg well personally, but the movie’s portrayal of him fits my impression of how he has allowed the platform itself to develop. I’m not at all a fan of Facebook. As I’ll explain later in the book, I regard the way it manipulates and controls our access to information as dangerous to the health of the Social Organism.

Still, in terms of the evolutionary process, Facebook has adapted brilliantly to the needs of the Social Organism—to a point. Within the evolutionary confines of the marketplace in which it has operated until now, Facebook has so far been the fittest survivor.

What did it get right? For one, since those early days in a Harvard dorm, Zuckerberg has opened his network up to the widest possible community. It has been designed to be deliberately mainstream. There’s a feel-good impression people get from using Facebook and an ease of use that makes it accessible to people far outside the tech-geek world. Everyone’s mom is now on Facebook. It’s a place where former high school classmates catch up, where families separated by oceans keep in touch, and where neighborhood communities share tips on lawn-mowing services and babysitters. It’s also where companies targeting that very same giant middle-class market of users can set up shop with a friendly page engaging in a “dialogue.” Facebook’s rosy veneer allows people to tell the story they want to tell. They construct an idealized version of themselves. Here’s me, with my face-tuned smooth skin and my perfectly beautiful family, living our happy and safe but also sufficiently exciting and varied life.

The platform is geared for this rose-colored form of expression, which for some time will create a comfortable arena for a mainstream market. Facebook’s subtle restriction of supposedly offensive content—a draconian posture that I personally experienced when they shut down my account after I’d cracked a joke in a private message—is also focused on the same goal: a sanitized, comfortable community. But my experience tells me that over time, they can’t have one with the other, that censorship ultimately constrains the Social Organism’s growth and leaves those providers that practice it vulnerable to conquer by more open platforms. It’s one reason I’m concerned about Twitter, Facebook, Microsoft, and YouTube’s agreement with the European Union that they censor hate speech. It’s hard to argue with the goal—I’m certainly no member of the #ISTANDWITHHATESPEECH movement—but executing on it becomes extremely complicated and can breed authoritarian instincts. As we’ll explore in chapter 6, trying to censor any speech is not only likely to fail but is harmful to our cultural development. It’s like spraying boll weevils with DDT. To eradicate hate we need to constructively boost empathy and inclusion, not censor it. As we’ll discuss later in the book, this approach matches that of contemporary cancer research, which is to train our immune system to recognize the disease and eliminate it with its own resources. By the same token, if we don’t expose ourselves to the sadness and pain of hate, we can’t recognize it and reject it.

This challenge to Facebook’s crown is already playing out. A host of new platforms has recently arisen, many of which deliberately flout the kinds of controls Facebook imposes. They reflect the next phase in the evolution of this life form. Right now, Zuckerberg’s empire is well entrenched and very unlikely to topple any time soon. But as the diversity of social media platforms expands, leading to greater competition for audience attention—much like the arrival of new, fitter species that compete with the old ones for resources—Facebook will eventually have to adapt or go the way of the dinosaurs.

Facebook’s biggest competitor, Twitter, might not end up the winner, but the difference in its approach is telling. It’s not well documented that Twitter—that quirky publishing system for messages of 140 characters that encompasses 320 million users and a staggering 500 million tweets per day—draws its ancestry from a community activism idea hatched down the road from Zuckerberg’s Harvard dorm. According to early Twitter engineer Evan Henshaw-Plath, one of Twitter’s stem technologies was the “TxtMob” SMS messaging solution for protesters that MIT Media Lab student Tad Hirsch first launched for anti–Iraq War activists who crashed the 2004 Republican National Convention. That edgy past is still in Twitter’s DNA, even though multiple pivots since have bent it to the commercialization demands of its investors. Arguably, Twitter came of age during the Arab Spring of 2009, when it was a vital tool during the street protests that led to the ouster of Egyptian strongman Hosni Mubarak. Those events forged a positive impression of Twitter—and social media generally—as a democratizing force that could foment political change. It’s uncertain whether that label still fits for a service that launched a $14 billion IPO in 2013 and is constantly trying to keep advertisers happy. But it does seem that Twitter’s more hands-off stance on censorship and privacy gives it a better chance of engaging with the fringe-dwellers—whether in Silicon Valley or Tahrir Square—who disrupt the establishment.

Then there’s the far more button-down LinkedIn, now owned by the white-washed Microsoft, which has focused on building business relationships. Yet in its own way, LinkedIn has had a decidedly disruptive and democratizing effect on how individuals form professional networks. In widening the market of searchable job candidates it has brought more meritocracy to recruitment, giving the Old Boys’ Clubs less clout. LinkedIn’s profitability stems from a business model that escapes the dependence on advertising by charging premium fees for special features. Depending on what happens with a bunch of new financial innovations, this subscriber-based model may become the template for other iterations of social media. (Not that it does a better job of encouraging people to show their “real” selves, warts and all. I chuckle every time I read the parade of inflated, grandiose résumés, each replete with the awe-inspiring buzzwords of “innovation,” “transformation,” and “disruption.”)

The other big names of social media show that there is much innovation under way outside of the heavy footprints of Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn. A form of digital biodiversity is forming in the sector. Whether each newcomer survives will depend on how well it adheres to the seven rules of the Social Organism.

Photo-sharing network Instagram, now a part of Facebook, might struggle in the long run. It instinctively censors content, which, we will repeatedly argue, denies nourishment to the Social Organism. Instagram’s policy of barring all forms of nudity has drawn derision for its heavy-handedness and, in particular, for its sexist double standards in differentiating between men’s and women’s nipples. Despite the company’s insistence that breastfeeding images are permitted, advocates for public breastfeeding say such photos continue to get blocked. The company claims its policy stems from rules set by the Apple Store for apps available to people under seventeen years of age, but those restrictions don’t seem to apply to the Twitter app and others that permit nudity. The bigger problem is that enforcing arbitrary rules depends on the discretion of the company’s in-house censors, who can easily veer to the absurd—as when Vogue creative director Grace Coddington was temporarily banned from Instagram for posting a line-drawing cartoon of her topless self. These ridiculous situations helped inspire the “Free the Nipple Movement,” a feminist movement meant to de-sexualize the female body that, coincidentally, had its birthplace in the country where I now live, Iceland.

In contrast to Instagram’s prudishness, Tumblr, the Yahoo!-owned microblogging social media platform, has a more laissez-faire approach. That it also happens to be a vibrant platform for avant-garde artists and animators to collaborate and push the boundaries of creativity is probably no coincidence—nor that teens use it as a place to outwit each other with their irreverent memes. Instagram might serve the interests of established artists like Beyoncé who want to feed their fans an image of impossible, airbrushed perfection, but Tumblr’s approach gives it a better chance of being an important incubator of the artistic ideas that will push our culture forward.

Now for Snapchat, a fascinating new phenomenon. The rapidly growing photo- and video-sharing app sets a time limit on each image for the designated recipient, usually a matter of seconds, an impermanence that in effect defeats censorship. Until very recently, the company claimed that its servers maintained no record of the communications so there was no archive from which to analyze the service’s 100 million daily users’ behavior. That policy was amended in the summer of 2016, when a new feature, called “Memories,” was introduced to allow users to keep a selectively shareable archive of their own snaps. But in this new opt-in model, the power to commit images to the server-backed collection remained in the hands of the person taking the photo, not the receiver.

A 2014 poll of 127 users by the University of Washington offered some clues as to how people used what was then an entirely transitory experience—and it was not, as you might expect, mostly for “sexting.” Some 60 percent said they primarily use it to share “funny content” and 30 percent said they use it to send selfies. Although 14 percent said they’d sent nude pictures over the service, only 1.6 percent did so regularly. The initial surge in popularity for Snapchat was in part about not wanting to produce a trail of behavior for others to later judge you by—whether it’s your future employer or your future lover—but it was also about living in the moment. As Snapchat founder Evan Spiegel put it in an early blog post for the launch, “Snapchat isn’t about capturing the traditional Kodak moment. It’s about communicating with the full range of human emotion—not just what appears to be pretty or perfect. Like when I think I’m good at imitating the face of a star-nosed mole, or if I want to show my friend the girl I have a crush on (it would be awkward if that got around), and when I’m away at college and miss my Mom...er...my friends.”

Snapchat represents carefree silliness and fleeting expressiveness. New filters allow for an endless stream of augmented human expression, which is why you can often spot some kid opening their mouth and raising their eyebrows to make silly faces at their cell phone. The model amounts to a very different value proposition from Facebook, and it appears to be gaining traction among the younger cohorts who will determine how the Social Organism functions in the future. A 2014 poll by Sparks & Honey showed a clear preference among Generation Z kids (those born after 1995) for Snapchat and other secrecy-enhancing services such as Whisper and Secret compared with more public platforms. That same study found that a quarter of that group had left Facebook in the preceding twelve months. In another 2014 poll, Defy Media found that 30 percent of people between the ages of eighteen and thirty-four—loosely conforming to Millennials—used Snapchat regularly. (In my adopted home of Iceland, a whopping 70 percent of its mere 320,000 citizens are connected on Snapchat. Let’s just say a party travels fast.) It has been reported that Snapchat turned down a $3 billion offer from Facebook in 2013. Did they make the Friendster mistake? Time will tell. For the sake of open, competitive platforms for free expression, their refusal to sell was a good thing.

Then there’s one of my favorites, Vine, owned by Twitter. This six-second video format, which forces creative self-expression into a narrow time window, has spawned an entirely new art form. One version: the “perfect loop,” a six-second, repeating piece of music that merges so perfectly you can’t tell where it begins and ends. Almost out of nowhere, Vine videos have become a vehicle for self-branded entertainment. It has turned a host of once-nobodies, many of them teenagers, into global marketing sensations. We’ll meet some of these Vine stars in the next chapter, but for now it’s worth pointing out that already many have audiences in the tens of millions, exceeding those of the world’s biggest newspapers. As of November 2015, Vine itself boasted 200 million users.

We start to see even more digital biodiversity if we head overseas. Although Facebook dominates South and Southeastern Asia, local platforms are big in North Asia. And it’s not just because of foreign website bans in China, where the most popular sites are Facebook-copy Renren and Twitter-like service Weibo. In more liberal South Korea, there is a preference for a local site called CyWorld, and in Taiwan many people use Wretch. Latin America, too, sports its own challenger, a site with 27 million registered users called Taringa! that uses bitcoin to share revenues with content providers. Life adapts to a given environment if it is to survive, and we see the Social Organism doing just that as it flourishes in different regions around the world.

Then, of course, there’s Google. With the merely modest success of its community offerings such as Google+, the world’s biggest Internet company has been less successful at founding social media networks—at least in terms of those services’ narrowest definition. But it is in all other respects the uber-networker of our age. Google Chrome is the most popular Web browser; in 2016, Gmail surpassed more than 1 billion monthly active users, making it the most used email service; first, Google Maps and now, Google-owned Waze have become the community-populated navigation services of our age; YouTube looks after our videos; Google Hangout is a go-to video conferencing service; the same could be said for Google Drive and Google Docs in terms of storage and file sharing; Android claims more than 80 percent of the market for smartphone operating systems; and, of course, the Google search engine has a virtual monopoly, which means the entire World Wide Web is designed to cater to it. We are all, in effect, algorithmically tied to each other by Google.

For all the legitimate concerns people have about Google’s immense power, its success is founded on the very principle of open platforms, interoperability and on an ingrained culture of open innovation. Yet the bigger question, one we will discuss at length later in the book, is whether its dominance—and that of Facebook and others like it—can remain compatible with the Social Organism’s evolutionary process. Google and Facebook are themselves products of an underlying trend toward decentralization, an extension of the unraveling of power from the Catholic Church to CBS and News Corp. to social media. And with new ideas around distributed databases, decentralized cryptocurrencies, and anonymous information, these new giants of twenty-first-century media will also find themselves confronting the ruthless algorithm of evolution. If they can’t adapt, they, too, will one day go the way of the dinosaurs and the newspapers.

Within the lifetime of a Millennial we have gone from online message boards and USENET groups to the communities attached to intranets like Prodigy and AOL, and from there to Friendster and Myspace and, eventually to Facebook and then Twitter, which together spawned Tumblr, Instagram, Snapchat, Vine, and others. Simultaneously, other decentralized models of human interaction are leveraging the Internet’s ever-expanding global, multinode network: online marketplaces like eBay; peer-to-peer lending; crowdfunding networks such as Kickstarter; reputation-driven asset-sharing services like Uber and Airbnb; bitcoin and other digital currencies; online open-source code repositories like GitHub. While not technically part of the social media industry, these technologies are part of the same amorphous, organically evolving force that’s shaping our culture and communities. They, too, define how the Social Organism lives.

As this new paradigm of hyper-competition grows, businesses designed around the old top-down model risk extinction unless they adapt. Centrally mandated corporate dogma and time-consuming chains of command are out of sync with the rapid demands of the Organism and the autonomous way in which it prioritizes how to occupy its limited attention quota. If brand managers, corporate PR teams, news organizations, politicians, and individuals want to get their message out, they, too, must move quickly. And that’s not easy when authorization systems depend on approval from the top.

Some traditional brands are showing they can adapt. During Super Bowl XLVII, Oreo embedded its senior brand management team with the 360i ad agency for the duration of the game, allowing quick authorization for sending out real-time messages to consumers. When suddenly there was an unprecedented blackout in the stadium, Oreo sent out a brilliant “You can still dunk in the dark” tweet, which was retweeted more than 10,000 times and received more than 18,000 likes in one hour—and shifted the conversation around how to make messages go viral. By contrast, when Disney bought my company DigiSynd and hired me in 2008 as an “insurgent” to open up its content and its social media presence, the first Mickey Mouse image I tried to put on Facebook as a promotional strategy took thirty days to garner approval from the Disney brass. How in the world am I going to keep up with an audience whose social fabric changes in minutes, if I’m waiting for a month for each piece of content?

The problem facing pre–social media institutions can be expressed in terms of the link between information growth and the evolution of computational capacity that we described in reference to César Hidalgo’s work. Whenever they process information to engineer products and services of value, individuals, firms, industries, and even entire economies will strive to gain more computing power. The competition for scarce resources demands it if they are to thrive and survive. Now that we have shifted information processing to a giant, interconnected network of human beings who are generating, sharing and processing ideas, that supercomputer’s power has exploded. What it means is that new, nimble smaller entrants into the market can access it at very low cost—a prospect that, for the first time, gives the little guy an advantage over bigger players. In effect, these upstarts are tapping into what might be described as a universally accessible global brain.

To Howard Bloom, the brilliant but slightly mad music publicist–turned–evolutionary theorist, life itself has always been evolving toward the optimization of a global brain. In his ambitious book The Global Brain: The Evolution of Mass Mind from the Big Bang to the 21st Century, Bloom frames this idea around human beings’ perennial battle with bacteria and other microbes—one we have occasionally come close to losing whenever pandemics like the black plague or AIDS arise. Bloom defines early-stage bacteria, which preceded all other forms of life on earth and took hold in the primal phase of our planet, as a giant data-sharing system. Devoid of the basic, membranous molecular form that most life would later assume and imbued with a capacity to share chemical signals across bacterial colonies, these microorganisms functioned, Bloom says, as a kind of network of computers. Together they collectively processed information about which version of their constantly morphing and adapting selves was the more superior and signaled that adoption of that structure. It seems as if this purpose—to process information and develop responses to it—is what got life started. Bacteria and viruses survived, even as more complex organisms started to arise out of the swamp. The microbes’ survival meant that human beings, in their constant battle with these nemeses, had to formulate combinations of group power to enhance their own organizational and computing structure.

Bloom’s idea might sound whacky when reduced to a few lines like this but it checks out with a lot of the research going into how microorganisms work as information-sharing networks. If he’s right, it means that when we combine social media’s organic interconnectivity of ever-expanding ideas with the powerful networks of supercomputers developing alongside it, we’ve arrived at a potentially transformative moment in our species’ survivability. Ray Kurzweil, the famous futurist and Google engineering director, believes that by 2045 the “singularity” will be upon us. That’s the point, according to his theory, at which computer-driven artificial intelligence reaches a kind of super intelligence that removes it from the control of inferior human beings and enters a process of rapidly reinforcing self-improvement cycles. If that A.I. machinery is designed to improve life for humans, it may well make us immortal, Kurzweil believes. More ominously, other Silicon Valley thought leaders, such as Elon Musk, worry that it could destroy us.

Bloom’s explanation of how we arrived at the global brain departs somewhat from the favored version of evolution theory spawned by Richard Dawkins, the great zoologist and renowned atheist. Dawkins’s notion of the selfish gene explained why much of the popular conception of Darwinism was wrong. To Dawkins—whose provocative take on memes will be addressed in chapter 4—the only reason group behavior emerged among animals, including humans, is because it suited the real architects of life, genes. He views both human flesh and the thought functions concocted by its biochemistry as mere vehicles for genes—he calls bodies “survival machines”—to raise the odds of their passage into the next survival machine once the current one reproduces. Everything, from altruism to social organizations like cities or corporations, is geared toward making that perpetuation more likely. Dawkins’s take, published in his 1976 book, The Selfish Gene, was a rejection of the popular idea that selfless behavior among animals was an evolved trait intended to assure the perpetuation of the species. The group’s interests have nothing to do with it, Dawkins argued; it’s all about the genes’ self-interest.

But now we have Bloom, with a powerful, long-arc theory that puts the idea of group interest back into the picture. To Bloom, the genome itself is a tightly coordinated group of units operating in concert for the common good. It sets the template for system designs that over time will show that the greater the diversity of organizational structure, the greater the survivability of the group—an idea that runs counter to the disturbing, exclusionary ideas of political figures like Donald Trump and Marine Le Pen and the British nationalists who successfully delivered “Brexit.” On this point, it’s not clear who’s right between Dawkins and Bloom, but we can be hopeful that this current moment, where social media has taken the Social Organism’s interconnected idea-processing power into overdrive, may bring us the answers.

In the chapters ahead, we’ll delve into the fundamental question asked by these two theorists: Why do we do what we do? And we’ll demonstrate how social media offers a laboratory to explore that.