CHAPTER THREE

THE AGE OF HOLARCHY

The Interconnected, Decentralized Cell Structure of Social Media

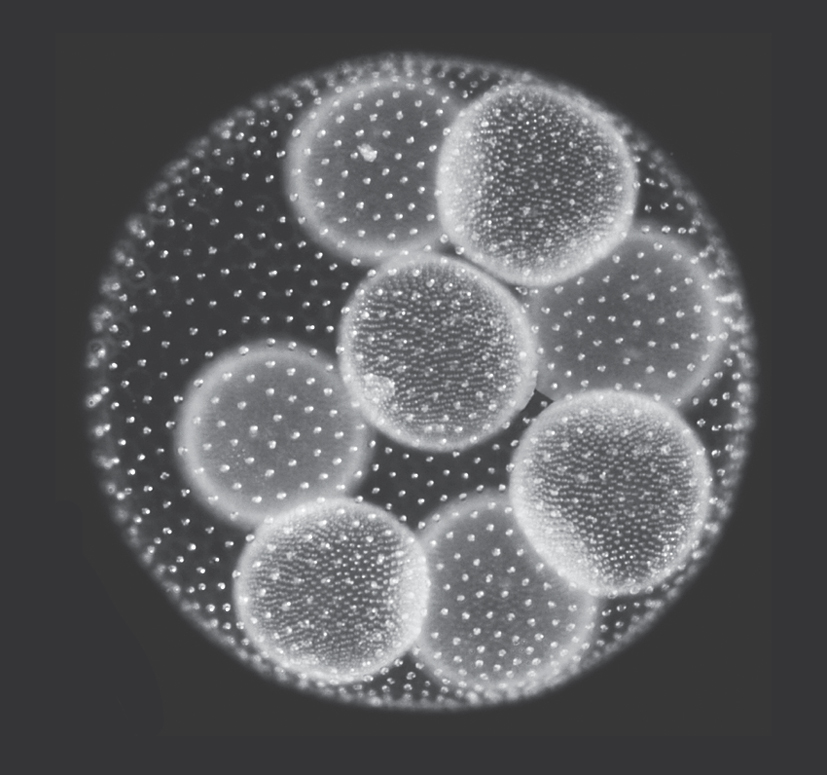

BACK WHEN I was a nerdy kid exploring life through my first Wolfe microscope—I still remember buying it from the Carolina Biological Supply catalog that Mrs. Franceschetti gave me—my favorite thing to find was a volvox, a green algae that forms spherical colonies inside pond water all around the world. Under the microscope a volvox was a beauty to behold: a perfectly spherical life form with tiny glowing green circles within it. In fact, although a volvox is classified as multicellular, it only took on this more complex form when, millions of years ago, its component single-cell organisms came together to form colonies. To this day, a volvox really functions as a group of fifty thousand unique organisms. They are connected to one another in a community matrix that forms a holonic structure—a state of interconnectedness in which unique entities exist in relation to one another. Each unit has the same basic form but differentiated purpose. Each is independent in its actions yet intrinsically part of a unified wider whole. In the case of the volvox, each organism develops different functions: some become photosynthetic receptors to generate energy for the community; some grow little flagella tails so they can carry out phototropic functions such as swimming toward the sunlight; some become daughter colonies to help reproduction.

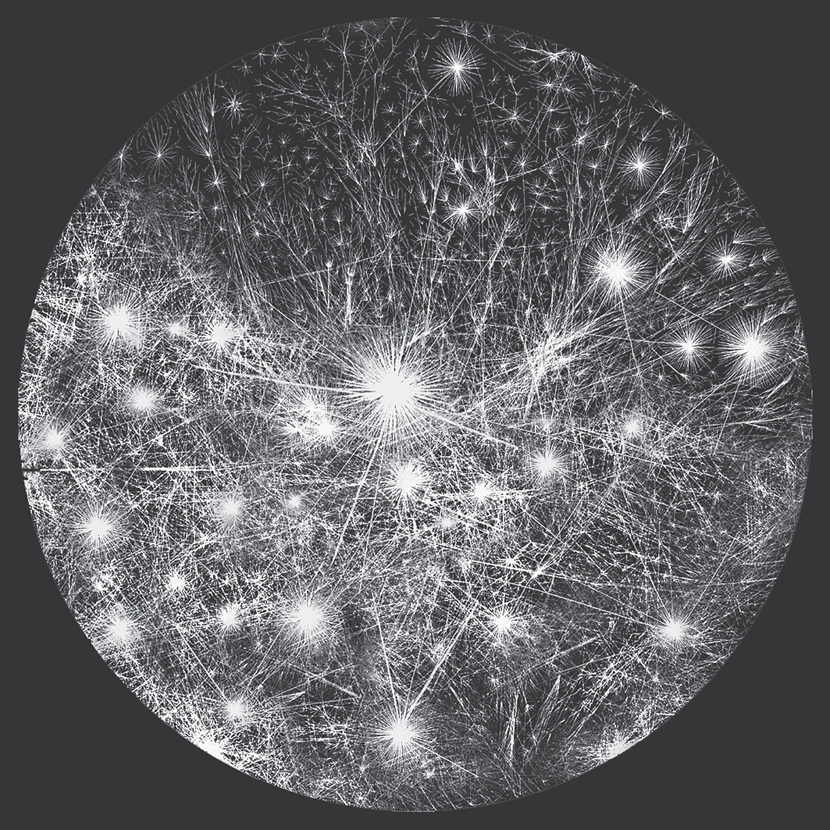

That image of a volvox immediately sprang to mind when I saw the spectacular Opte Project’s artistic visualization of the Internet, which hangs in New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Created with a sophisticated program that produced images upon images of every network’s relationship to each other in the online world, it makes for a striking juxtaposition when placed against a microscope-produced photo of a volvox.

In the Opte Project image, we see the decentralized interconnecting network of billions of nodes. It has become a template for many other visualizations produced for analyses of social media phenomena—for illustrating how a particular phrase or piece of news flows across the network, for example, or for how social networks of “followers” and “friends” tend to coalesce and form bridges. In all of such graphics, the bright spots, just like those in the Opte image, represent clusters of connectedness, the hubs from which our human connections emerge and interconnect. In a social media context, they are celebrities, brands, original thinkers, influencers, and anyone who’s attracting a mass audience. Like the cells within the volvox, the clusters that form around them extend to make connections with the rest of the organism and thus to push out the message. It’s consistent with the first defining characteristic of life, Life Rule number one: All living things have a cell structure. A corollary to this rule is that the more complex the organism, the more specialized and differentiated its cell types will be.

Volvox

“The Internet”

What does that mean when applied to the Social Organism? On the most simple level, the breakdown of the Social Organism’s structure, roles can be split into influencers and followers. But in just a few short years, we’ve seen more complex and niche roles emerge. The classifications would also include artists and other creative types who turn existing ideas into new derivative versions of the art—which we can think of as hybrid memes—as well as trolls and other disruptive elements that challenge, redirect, and contain the flow of thoughts. Each depends on the others, and without their combined interactions the Organism could not live or sustain equilibrium.

In the following pages, I give a snapshot of some social media elites and their networks, which offer some key insights into the Social Organism’s cell structure. Just like my beloved volvox, the relationships between the component cells in a social media network can be described as a holonic structure, where every entity is both an autonomous whole and part of a larger system of interdependent, self-regulating hierarchies. Holonics describes the order of the natural world, but an order that arises organically, without centralized control. Because such ideas are the antithesis of the vertical, command-and-control systems perpetuated by Western capitalism, they can seem contradictory to minds that are raised in that tradition, minds that imagine the absence of central authority as a recipe for chaos.

But make no bones about it, there is order in the Social Organism. And that creates opportunities for those who recognize it. For while others see chaos in the social media universe, those with insights into this holonic structure are making a fortune by tailoring their networks to it.

Visualizations of social media clusters that follow the Opte image template shown on page 50 tend to mask the fact that the power relationships within this new communications architecture are in flux. As a function of the Organism’s rapid, evolutionary state, the roles and status of influencers are always changing. When I founded theAudience in 2011, our first clients were people like Hugh Jackman, Charlize Theron, Mark Wahlberg, and Russell Brand—pre-established celebrities who were using social media platforms to maintain and build their brands. As my cofounder Sean Parker put it, these were the “digital immigrants,” non-natives in the online marketing world who sometimes reluctantly dove into social media because their handlers told them it was necessary or because social media followings were becoming a measurement of worth.

Once the system for determining what content gets distributed shifts from one where it was decided by studios and record companies to that of a holonic structure in which autonomous individuals did so in concert with each other, big changes in the pecking order of the creative industries were inevitable. We’re now seeing entirely new spheres of influence developing around networks of connected human beings, with an entirely new kind of celebrity sitting in the middle. They are people like Vine star Nash Grier, a prolific producer of silly, six-second video vignettes.

Grier’s Vines project a lifestyle and way of being that taps into the imagination of a whole generation of digitally connected kids. He is witty, somewhat mischievous, irreverent, and moderately self-deprecating, yet also cool and, importantly, not too threatening. His jokey, slapstick clips exude a vision of carefree existence that’s projected as if it belongs entirely to his generation; it’s not a world that older folks can participate in. By connecting on that level he has accumulated millions of fans, many of them adoring females but also hordes of young men who want to be like him. By 2013, when he was just fifteen, Grier had amassed 6.8 million Vine followers. By mid-2016, that number had swelled to 12.7 million, encompassing a group of fans who had watched his clips a total of 3.4 billion times, as measured in “loops.” Grier also had more than 5.5 million Twitter followers by then, a group that included numerous accounts set up purely to keep track and retweet everything he does or says—a network of sub-influencers working for a central influencer, an ecosystem within his own ecosystem. These sprawling tentacles of fans give him the same reach as most cable networks. Grier’s currency is his digital persona.

Grier joins a host of Generation Z-ers and Millennials producing voyeuristic glimpses into their lives, a genre that’s suited to short-form Vines and short-lived Snapchat messages. With their endless feed of vignettes—sometimes delivered as staged jokes and pranks, other times as brief windows into their “chill” existence—life emerges as a series of fleeting, transitory performances. Vine’s jumpy, low-budget aesthetic, which eschews the brash glamor of Hollywood celebrities and instead contrives the star as an everyman, is the format’s magic sauce. Despite the real-life mega-stardom that many of these leading “Viners” have attained, they convey a down-market image of lovable, knockabout kids. Beneath that anti-establishment image, however, these new celebrities are forming their own kind of organizational strategy, one in which they all feed off and reinforce each other’s reach and influence.

The format has proven to be a winner among young followers and spawned an entire industry and subculture. Not surprisingly, it has also attracted some big advertisers. Coca-Cola, Hewlett-Packard, Procter & Gamble, and Warner Bros. have teamed up with Viners like Cody Johns and Greg Davis Jr. I routinely saw six-second spots with Nash Grier going for $25,000 to $35,000, and he’s been known to attract as much as $100,000. Ritz Crackers got teen Vine star Lele Pons—the highest ranking female Viner, with more than 10 million followers and the largest number of total loops overall at 7.5 billion—to insert her prankster persona and slapstick style into an ad that involved her stealing unsuspecting people’s crackers. The world’s most successful Viner, Andrew Bachelor, better known as King Bach (15 million followers, 5.6 billion loops), has turned down loads of offers to do sponsored Vines but has nonetheless monetized his fame by landing lucrative TV and film roles from Black Jesus to The Mindy Project. In March 2013 King Bach posted a six-second “Ghetto Beat Down” derivative version of the Chainsmokers’ #Selfie song, which theAudience had promoted. His video exposed a huge new digital audience to the song and pushed the daily views of the original #Selfie video from 800,000 to over 1.5 million during a sustained two-month period. It was a compelling example of how these uber-influencers have developed the capacity to tap this new organically interconnected network structure to rapidly spread information.

For its short content, Vine is also an oddly successful platform for music promotion. Husband-and-wife team Michael and Carissa began recording folk-pop music in 2011, but once they started putting six-second loops of themselves up on the platform, their career took off. A year later, they signed with Republic Records, marking what is thought to be the first ever deal spawned from Vine. Around the same time, Canadian singer-songwriter Shawn Mendes launched himself on Vine at the age of fifteen; two years later he had 4.5 million followers, had recorded two albums, had opened for Taylor Swift’s world tour, and his “Stitches” single had reached number one on the Billboard charts. Jack & Jack (6 million followers, 1.8 billion loops)—high school buddies who became a comedic duo on Vine and with whom I worked to package content and advertising deals—have also topped the iTunes charts with songs like “Wild Life.”

Then there are the YouTube millionaires, whose ranks include some very young stars. The most lucrative model: doing reviews of toys. By the age of eight, Evan of the YouTube channel EvanTubeHD, was earning an estimated $1.3 million in ad revenues for reviews filmed by his dad. Two Japanese children, Kan and Aki, appear to be even younger and were earning an estimated $3.2 million for their “reviews” in 2013. The biggest earner on YouTube is the unidentified owner of a site called DC Toy Collector, which never shows the face of the elaborately nail-painted hands of what appears to be a young girl opening and assembling Disney toys. The site earned $4.9 million in 2014, according to video data analytics firm OpenSlate—more than second-ranked YouTuber Taylor Swift earned for ads on her videos that same year. The third biggest YouTube earner is PewDiePie, a Swedish game commentator—a popular genre that involves recording a running commentary over the top of a filmed video game. With 40.9 million subscribers and over 11 billion views on his videos, he earned $4 million in 2014.

I’m going to guess that, perhaps with the exception of Taylor Swift and, maybe, Shawn Mendes, the names listed above are new to most of you reading this. They’re not what most people of my generation or older would typically call “household names.” Yet their ability to reach a targeted audience is more advanced than most established media outlets. Any brand or institution that wants to properly reach a major audience must come to grips with this new architecture and the powerful intermediation of these new, independent stars.

Social media’s infrastructure of human networks is by no means an evenly distributed population of influence. If Twitter were a nation and follower numbers were dollars earned, it would look far more unequal than the American economy’s notoriously skewed income distribution. A survey by O’Reilly Media in 2013 found that those Twitter accounts in the top 1 percent of follower tallies averaged 2,991 followers, a figure 50 times the average of those at the 50th percentile. (In terms of U.S. income, the top 1 percent has an estimated eight times those in the middle.) Go up to 0.1 percent of Twitter accounts and the difference with the median is a factor of 409. And that was in 2013, when that group averaged just 20,462 followers. What’s more, it took no account of what we might see as the “Bill Gateses and Warren Buffetts” of Twitter’s skewed influence distribution curve, the mega-influencers that claim more that 40 million followers, people like Lady Gaga, Justin Bieber, Katy Perry, and that uber-celebrity, President Obama.

It’s worth also noting that the unequal influence distribution correlates with earnings. Only the elites, those at the very pinnacle of follower tallies, are killing it financially. Like brilliant footballers or basketballers who dominate college competitions but can’t break into the professional leagues, YouTube, Vine, and other ad-earning platforms are filled with talented, almost-making-it types. People like Brittany Ashley, one of the biggest and best-known stars on BuzzFeed’s four YouTube channels, which together account for 17 million subscribers. Ashley might have 70,000 Instagram followers but she still has to wait tables at a restaurant in West Hollywood to make ends meet. As Fusion writer Gaby Dunn noted in a piece about Ashley and other online personalities who get hounded by fans at their day jobs, “[m]any famous social media stars are too visible to have ‘real’ jobs, but too broke not to.” Efforts to create mutual sharing agreements so that users can pool their follower networks, including that of the Shout! project by MIT Media Lab’s Macro Connections group, might one day improve the economics of social media for little guys. But for now, when compared with more than a billion users worldwide, the winnings in social media appear to be extremely concentrated in the hands of a few.

Still, there’s no denying there’s been a major power shift toward the handful of newcomers who’ve fully mastered the art of social media marketing. Whether it’s self-employed powerhouses like Grier or BuzzFeed’s slightly more professionally produced YouTube channels, these people have something marketers and communicators want: command of a massive and directly targetable audience. How should we view this in terms of the evolution of mass media? In garnering such influence and audience, has this handful of instant millionaires simply converted themselves into a new oligopoly over cultural production? Are these teenage pranksters, with their often inane, mildly narcissistic statements on life’s absurdities, the new commanders of our communication system? Are these zany kids now occupying roles that were, in times past, held by the church, newspapers, and TV networks?

Well, to a degree, yes. But this is key: These newcomers’ grip on the fulcrum of power is tenuous. Their dominance of the market is not backed by economies of scale as it was for traditional media companies; they’re not protected by the barriers to entry that old newspaper giants enjoyed when it was too costly for smaller competitors to invest in printing presses and delivery trucks. Rather, the social media influencers’ power is instead founded on the trust and emotional connections they’ve built with their fans and friends. Social media stars are nothing without the cooperation of their followers and of the privately owned platforms where they distribute their content. In biological terms, these uber-users are what epidemiologists view as “super spreaders,” those especially contagious types that play outsized roles in the dissemination of biological viruses. (Super spreaders typically account for about 20 percent of a population but have been shown to be responsible for 80 percent of all infections during epidemics.) Regardless of their mega-contagiousness, however, super spreaders’ impact is only as strong as the receptiveness of others in the population to the virus they are spreading. To maintain influence, social media elites need their followers to consistently repeat, replicate, and share the ideas they generate. It’s a distribution network that depends entirely on an ability to connect with other people who are willing to share the information you provide them.

These influencers’ power lies in their ability to build networks. They do this not by laying out fiber-optic cable but by forging virtual personal bonds. The strategy is twofold: On the one hand, they cultivate a very large army of fans, focusing on delivering content that serves their viewers’ emotional needs; on the other, they forge tight social ties with other strong networkers, partly by impressing them with their work but also through personal connections. By tapping this inner circle of uber-influencers with very large fan bases, they can launch messages into a gigantic network very quickly.

With Nash Grier and King Bach leading them, a Rat Pack for the digital age has arisen, including: Jack & Jack, Matthew Espinosa (6 million followers), Nash’s own brother Hayes (4.2 million followers), Shawn Mendes, and, for a time, a young provocateur by the name of Carter Reynolds (4.4 million followers). They collaborate by doing cameos in each other’s Vines, appearing in each other’s music shows, and—most important—reposting each other’s blogs. (At theAudience, we called this cross-popularization.) All of them moved to Hollywood to be able to coordinate their daily lives together. It’s like a living reality show, playing out constantly on social media. And in a unique, social media way, they are building a kind of modern oligopoly in which celebrity and influence are the barriers to entry.

Yet those protective barriers aren’t as formidable as those that monopolies in the brick-and-mortar world enjoy. The challenge confronting the Viners’ Rat Pack oligopoly is that social networks that are founded on mutual interest can fall apart when someone acts counter to those interests. In the old media structure, the top-down hierarchy provides a check on what goes out: Material is carefully vetted to try to ensure that nothing is released if it could undermine the media company’s market position. But in the holonic structure of the Social Organism, where both makers and distributors of content act autonomously, such calculated control over content isn’t possible. And here’s the thing: People, especially teenagers, make mistakes.

The speed with which Carter Reynolds lost control of his distribution system speaks to this problem. Reynolds was one of the biggest names on Vine until midway through 2015, when a hacker obtained and leaked a video of him pressuring his sixteen-year-old girlfriend and occasional Vine co-star, Maggie Lindemann, to have oral sex. There followed a series of very public meltdowns, failed attempts at contrition, and a major Twitter war with Lindemann that earned its own trending hashtag, #MaggieandCarter. The defining moment was when Reynolds produced a long, rambling video, during which his phone beeped with what he told the audience was a threatening text from Maggie and then proceeded to explain how he’d been told that “she sucked Hayes Grier’s dick.” This was the same Hayes Grier who is the brother of Vine superstar (and devout Christian) Nash and with whom Reynolds had often worked. The whole sordid affair played out to millions of people. Not surprisingly, Reynolds’s advertising dried up. Just as important, he was cut off from the Vine Pack. As of late 2015, Reynolds’s Vine page still showed a following of more than 4 million and, with his notoriety sustaining some level of fascination, his post-scandal Vines still received just over a million views. But that figure was well below half of the multimillion loops he was clocking in the first half of that year. By 2016, his Vine output completely dried up, with his page showing just three “re-Vined” clips made by other Viners over the course of the first six months of the year. Without the shout-outs on Twitter, Instagram, and other platforms from his well-connected former buddies, he didn’t have the same audience reach. In the Social Organism, those that giveth taketh away.

Social ties and networks are the very foundation of these young stars’ fame. And they can break. People like Carter Reynolds can fall so rapidly out of the public eye, when even scandal-ridden celebrities from more traditional areas of entertainment often ride on their fame for longer: Tiger Woods, Mel Gibson, and so forth. The lesson here is not that social media influence can be both powerful and fleeting. It’s that to be effective and sustainable, the social network needs to be constantly maintained and nurtured for the re-blogs, re-tweets, re-posts, and shares to keep going. Life Rule number four: To maintain this steady state of homeostasis, the Organism’s metabolic pathways—in this case, social connections—need to be open and unbroken.

We learned a great deal at theAudience about maintaining ties with followers. Our relationship with the influencers we’d brought into our network was critical to its success. Through these well-defined bonds, a message could be fanned out to a global mass of hundreds of millions of people very quickly. But equally crucial, our influencers had to manage their own networks. They needed to keep their own followers actively engaged, with a steady stream of nourishing content that helped cultivate trust and loyalty. Doing so is what constitutes network maintenance in the social media age. Whereas network maintenance at a traditional TV channel refers to the upkeep of cameras, broadcast towers, and cables, in social media it’s all about emotional maintenance. Viewers and readers are no longer just an audience; they are also a distribution mechanism.

In pop culture, Taylor Swift is the queen of network maintenance. She is arguably the most powerful woman in show business. (Eat your heart out, Oprah.) She alone stood up to Apple, the most successful consumer product maker in the world, and forced the company to change its artist royalties policy overnight, simply by publishing an open personal complaint letter to the company. The power of that letter was not based simply on the quality of her music but because she had an army of loyal followers behind her. With more than 50 million Instagram followers, the highest ranking on that site, and a Facebook page with 73 million likes, Swift commands the attention of a population bigger than France’s.

But it’s Tumblr that’s become the singer’s preferred stage for performing the character called “Taylor Swift.” On Tumblr, Swift has cultivated a deep sense of trust, sincerity, and genuine affection with her young fans, a global community that self-identifies as “Swifties.” She has done this by doing things like turning up on the doorsteps of some of them with personally delivered Christmas gifts and posting videos of the surprise visits. Alongside action shots of the singer strutting her long legs before stadiums filled with screaming fans, Swift’s feed offers images and one-liners that, like the Vine stars, seek engagement through a common touch: selfies with her cats, shots of her hanging out in pajamas, hugs with her girlfriends.

To be sure, Swift’s BFFs aren’t exactly commoners. Her well-documented friendships with other influential young women include fellow singer Selena Gomez and fashion model Karlie Kloss, offering another reminder of how a powerful inner circle of fellow influencers can maximize clout. The star pull of the former child actor Gomez—who sits just two spots below Swift’s number one spot in Instagram rankings—is impressive in its own right. She wins over the teen crowd with a persona that veers more toward the good-girl-gone-bad image (Miley Cyrus’s forte) than does Swift’s more wholesome self-portrayal. Many attributed the breakaway success in 2013 of Spring Breakers, the dark gangster romp from director Harmony Korine for which we at theAudience designed an unorthodox and highly successful marketing strategy, to the widely shared animated GIF, lifted from the movie, of Gomez smoking a bong. Her seductive self-branding is also fueled by her rocky former relationship with bad boy pop star Justin Bieber, the owner of the second-most followed Twitter account after Katy Perry and the fifth-most followed Instagram account.

But it’s not just sex and close-knit celebrity partying that sells. Taylor Swift’s careful strategy for fan management/network maintenance employs a much more personal touch. Just as Bill Clinton’s capacity for empathy was key to his prodigious skills as a political networker, the twenty-five-year-old demonstrates how far humane gestures carry influence. When the hashtag #ShakeitupJalene alerted Swift to the fact that the final wish of Jalene Salinas, a four-year-old girl diagnosed with terminal brain cancer, was to dance with the star to “Shake It Off,” the singer set up a Facetime call with her and her mother. Television cameras recorded the tear-jerking moment. Another time, she donated $50,000 to eleven-year-old Naomi Oakes, who was battling leukemia. A tearful Swift also gave a shout-out during a concert to the mother of another four-year-old who’d just died of cancer, sharing the fact that her own mother had been battling the disease.

Swift’s charitable gestures may simply be contrived and self-serving. But even if they are, it’s hard not to be impressed by the grand, international scale of her fan/follower management. It takes real talent to succeed in making someone feel like they are being spoken to personally when they are one of 75 million; these little acts of soft touch can create that illusion. Taylor Swift’s fans feel a very deep bond with her—arguably more so than the “Rihanna Navy” population feels with their idol, Rihanna, whose social media image (primarily on Instagram) depends more on glamour and sex appeal than on personal connections with fans.

Swift is clearly a talented and hardworking performer. But the rest of it—the empathetic, big-hearted, all-around-nice-person image that she presents on social media—is also important. They form two parts of the same, combined package. Together, they demonstrate how the mechanics of fame work in this new era, where communication networks are managed with emotions. Since social media occupies a holonic structure in which the autonomous members of the network represent both the target audience and the distribution system, emotions are now the primary tool for spreading ideas and artistic works.

Nature does not have a dictator, benevolent or otherwise, telling it what to do—notwithstanding the millennia-old debates over the existence of a God. Neither do social media networks. This holonic structure offers not just a useful way to think about the Social Organism, but a satisfying, all-encompassing explanation for life itself.

Holonics can be described as a field of biological philosophy, though it also draws from physics and systems design. Developed by Arthur Koestler in the 1960s and furthered by the likes of Ken Wilber, the notion has fallen back into favor as the online economy has rekindled network theory. Holonics recognizes that the world comprises interdependent hierarchies and sub-hierarchies known as holons. (The word “holon,” like “holistic,” stems from the Greek word “holos,” meaning “whole, entire complete.”) Each holon is an autonomous whole in its own right and at the same time is a part of, and dependent on, an even wider whole, which in turn constitutes another, higher-level holon. A holon’s status is inherently dualistic; whether it is a whole or a part depends on how you look at it. Together, holons form a progression of interdependency like an ever-growing stack of Russian matryoshka dolls.

The idea builds out to what is, in effect, a theory of everything. It’s the kind of all-encompassing idea that could only take root in the broadmindedness of someone like Koestler, a brilliant polyglot intellectual of Jewish-Hungarian roots who lived all over Europe and flipped between left- and right-wing philosophies throughout a life that defied categorization. Koestler was born in Budapest, educated in Austria, and spent his early adulthood on a kibbutz in Palestine. He joined the German Communist Party in the 1930s right when Germans were warming to Hitler’s Nazism and then worked as an anti-Franco spy on behalf of the loyalists in the Spanish Civil War. But later, after becoming thoroughly disillusioned with Stalin, he converted into a hardline anti-communist crusader from his adopted home in London. He was a prolific journalist, essayist, and novelist, writing articles and books of fiction and nonfiction that covered the gamut of biography, philosophy, physics, biology, and religious studies. In 1983, suffering with Parkinson’s disease and newly diagnosed with cancer, Koestler and his wife, Cynthia, jointly committed suicide by overdosing on barbiturates and alcohol.

Holonics, the concept that arose from the holon theory that Koestler first expounded in his 1967 book The Ghost in the Machine, is perhaps his greatest contribution to Western thought. In a sweeping critique of the centuries-old prevailing human belief that the universe is defined by some centralized authority that established human domination, a model that gave birth to the horrors of the Holocaust and Stalinist authoritarianism, he offered the holon as an alternative construct from which to understand the nature of existence. To introduce this idea, Koestler retold the parable of two watchmakers that Nobel Prize–winning scientist Herbert A. Simon used to explain how complex systems form out of simple systems. In Simon’s story, two watchmakers both make fine watches out of a thousand tiny parts. While they work, both must field frequent phone calls that interrupt their work. One watchmaker succeeds while the other fails. Why? Every time the unsuccessful watchmaker put down his unfinished watch to answer the phone it would fall apart, requiring him to build it from scratch. By contrast, the successful watchmaker built his watches from parts that were assembled into sub-assemblies of ten parts each, a modular arrangement that would hold together when it was put down. This basic idea—that stable, intermediate forms provide intermittent foundations upon which complex systems develop from simple systems—leads to the overarching concept of the holarchy. It’s an idea that speaks broadly to how life takes form, how ideas develop, and how, in this seemingly chaotic world of social media, billions of autonomous nodes somehow, despite themselves, follow a degree of order and structure.

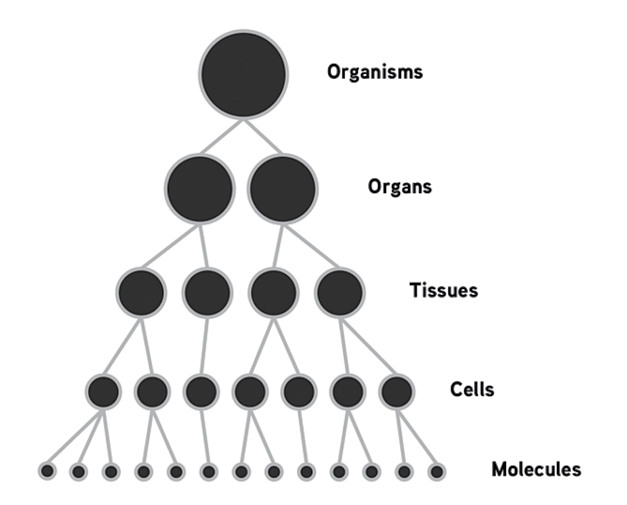

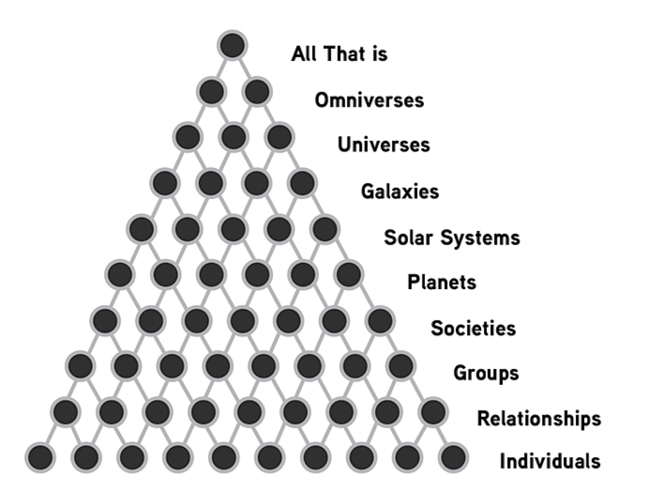

If you look at the picture of the volvox, with its spherical components comprising arrays of smaller spheres, you’ll see how Koestler’s model fits with microorganisms. But holonics equally describes more complex organisms, and even the ecosystems in which they exist, spreading out from the tiniest molecule to the structure of the entire universe (or multiverse, if you prefer). If we take the concept “sheep,” we can see that holonic hierarchies exist at each stage of the progression from biochemical compound, to cell, to organ, to the sheep’s body, to the flock of the farm in which it lives, to its breed (Merino, say), to the species Ovis aries, and so on until these increasingly wide collections of units incorporate the biodiversity of the entire world. Each unit (holon)—be it the cell, the multicell organism of the sheep itself, or the flock to which it belongs—is simultaneously independent of and dependent on the wider group to which it belongs. As per the two diagrams below by Flemming Funch, a futurologist, philosopher, and systems designer, we can use this structure to describe a biological holarchy or that of a universal holarchy that lays out the overall dominions of life.

In fact, the beauty of Koestler’s model is that we can apply it to any reference of existence, including social media networks. It explains the relationships between influencers, their inner circles of co-

influencers, their combined clusters of followers, the wider platforms for sharing information, and the much, much wider ecosystem of the entire Social Organism. As with the holarchies of the natural world, the Social Organism has no formal leader, whether democratically elected or self-appointed. Instead, it’s founded on a digital framework of interdependent relations that facilitates the system’s own evolution and expansion.

To be sure, the Social Organism is currently not a very well structured holarchy, not in the idealistic terms of how well it serves the public interest, but understanding its organization will help us improve upon it—in fact, it’s crucial to the technological future. In biology, holonics describes how social insects such as bees, termites, and ants work together. There’s no central controller inside the mound dishing out orders to the termites; rather, each termite is genetically “programmed”—in its case by the great evolutionary algorithm of time—to respond to what it senses from its peers in a way that optimizes the group’s interest and is influenced by biological signals. Now imagine a Google engineer who is designing self-driving cars that will interact with a fleet of similarly designed cars—all intended to optimize the traveling experience for the full community of passengers. There will be no super-command computer at Google headquarters directing all the cars like an airport control tower; rather the system will work because each car is individually programmed to respond to what it senses the others are doing and will adjust its “behavior” accordingly. This approach allows Google’s engineers to design a holonic, leaderless transport system that can deliver all passengers to their destination more quickly and safely than in the current world of human-driven cars.

And while they might bristle at a comparison to termites, the Vine Rat Pack and Taylor Swift’s BFF team are also “workers” in a holonic structure of creation. They’re not constructing a termite mound or an efficient traffic pattern, but with their collaborations they are creating personas. Each influencer is autonomous in their creativity but at the same time works within the common whole of a set of shared values or patterns of thought. These shared values allow them to relate consistently to their audiences and become the basis upon which their followers engage in emotion sharing. When a single Vine, Twitter, or Instagram user relates to another within the Social Organism, they express themselves through the borrowed persona of one of these influencers. This then in turn becomes their persona. (Here we’re talking about a much more fluid concept of the self than traditional liberal Western ideas of identity and personality. It’s a concept we’ll get to in chapter 5.)

As the Social Organism evolves and our means of communication move further away from a traditional, equipment-heavy media distribution model toward one founded on the holonic relationships between autonomous minds, the rest of society is going to have to reorganize, too. A good place to start is with that mainstay of capitalism: the company. We’ve already discussed how old style media companies’ top-down authorization protocols and proprietary obsessions prevent them from keeping up with the rapid demands of social media. Similar problems are also arising in other pre–social media firms.

The most important objective of any organizational design is to facilitate efficient communication flow—internally among employees, work groups, managers, and shareholders, and externally with suppliers, contractors, customers, and the public—in order to optimize decision making and maintain a competitive edge. But now incumbent businesses that have relied on top-down communication are losing their edge, because social media and other online technologies let smaller, more nimble start-ups process information more efficiently. Instead of relying on their own narrow pool of thought capacity, these newcomers are leveraging the Social Organism’s global brain, where ideas, content, and products are seamlessly shared without heed to geographical, national, or cultural boundaries. They’re tapping a universally accessible system for creativity and computational capacity, a giant pool of potentiality that renders the old monopolies over information obsolete. The only way for incumbents to compete with this is to reorganize. To do so, they’ll have to learn from the newcomers.

Salim Ismail and a team from Singularity University have a word for the most successful of these newcomers: exponential organizations. As they argued in a bestselling book of the same name, rapid, globally scaled growth is now possible if firms are willing to tap resources outside of their organization rather than depend on proprietary idea generation and implementation. This is not merely an outsourcing concept aimed at reducing costs; it’s that external partnerships are the only way to rapidly build massive transformative networks, the only way to properly unleash new ideas and build new markets. To achieve this, firms must also be reorganized internally, with horizontal command structures that give greater autonomy to employees and encourage cooperation within and across self-organizing work groups. An exponential organization is one that favors symbiotic partnerships and collaborative projects over top-down, vertical control of the means of production. In such a firm, ownership and control are shared concepts.

One example is Chinese smartphone-maker Xiaomi, which relies on a fan base of 10 million “Mi Fen” followers to help steer product improvement. Non-employee users developed all but three of the programming languages available on Xiaomi’s smartphone operating system; they also run the company’s support system via a peer-to-peer advice platform and help keep the company’s marketing costs low by voluntarily promoting its products over social media. What do these fans get in return? They get to engage in the development of an ever-improving and highly affordable line of smartphones that has in three years come from nowhere to become one of the five biggest in the world and is lapping at the heels of Apple and Samsung. That’s emotionally satisfying.

Xiaomi is also a great example of how organizations need to restructure internally if they are to keep up with the fast-changing world of the Social Organism. Its work teams are conceived of much like clans or tribes, without strict lines of control. Emphasis is placed on mentoring, collaboration, and adhocracy, with profit sharing as a key incentive. Job rotation is encouraged. Worker autonomy is a key goal, so, too, is loyalty to the group. In that way it captures the parts-to-whole duality that’s central to the concept of holonics.

Few have gone as far in formulating a defined management strategy around holonics as consultant Brian Robinson. He calls the ideal organizational design a “holacracy,” a name that draws directly from Koestler and which Robinson’s firm, HolacracyOne, has registered as a trademark. Rather than a pyramid structure based on authority, subordination, and control, Robinson’s holacracy involves “circles” in which individuals are defined by their “roles” rather than by their titles. Such people have autonomy over decision making pertaining to their role, but they are compelled to address “tensions” within their circle before deciding on action and have no control over any other role.

Shoemaker Zappos.com is the poster child for the HolacracyOne model. CEO and founder Tony Hsieh, who is worth almost $1 billion but lives in a 240-square-foot Airstream camper in a communal trailer park in Las Vegas because he “really like[s] the unpredictability and randomness of it,” has become a passionate believer. Hsieh wants to rearrange his firm so that it no longer has him, or anyone, at the helm. On its website, Zappos describes holacracy this way: “It replaces today’s top-down predict-and-control paradigm with a new way of achieving control by distributing power. It is a new ‘operating system’ that instills rapid evolution in the core processes of an organization.” Hsieh says he wants to emulate what happens in big cities, where innovation and productivity per resident increase 15 percent every time an urban area doubles in size, rather than accept the declining productivity that has traditionally hindered companies as they expand.

Implementing a holacracy is not easy, especially not in a firm like Zappos, which had operated since 1999 under a more traditional structure until Hsieh started to mix things up in 2012. When, in March 2015, he wrote an email to the company’s 1,500 staff and offered severance for those who couldn’t embrace the new culture, a surprisingly large 14 percent of the staff accepted it. Still, it’s way too early to suggest that Zappos’ experiment has been a failure; in fact, removing those who resist change may be exactly what’s needed for success.

The exciting thing about these kinds of ideas is that, when taken to their highest level, we could reimagine an entire new societal arrangement, one that’s less oppressive, more egalitarian, and more capable of unlocking the best in people. These are extremely lofty goals, the kind that have dogged philosophers and political scientists for centuries. How, though, might these ideas help us attain these goals in the era of social media?

Mihaela Ulieru, a researcher in intelligent systems design from Carleton University, offers a roadmap—and, perhaps not surprisingly, it comes down to how we treat each other, to the social mores of our culture. A necessary element of holarchic organizational design, she says, is that it unquestioningly recognizes the fundamental duality of a holon: that an individual is defined both by their independent sovereignty and by their membership of a wider collective group. She says this requires that people simultaneously embrace two different ways of perceiving the world. One of those is the “subject/object way of knowing,” which she describes with the example of a bag of groceries that all individuals (subjects) can objectively agree weighs twelve pounds. The other is the “subject/subject way of knowing,” an approach that’s “rooted in an individual’s subjective [and private, internal] experiences of the world.” The latter perspective would recognize that the “bag of groceries that objectively weighs twelve pounds may feel subjectively lighter to an athlete but heavy to a frail, older person.” Western societies have overly emphasized the first perspective, Ulieru says, but have typically downplayed the subjective differences between how people perceive the world. Incorporating the latter into our decision-making framework—an exercise that she says requires empathy—is thus the biggest challenge we face in designing holarchic systems.

Imagine now what Ulieru’s schema might look like if applied to an optimal social media world. For now, it’s hard to see much room in social media for the subject/subject perception model. All the mudslinging and quick-to-conclude responses of trolls and shit-stirrers on Twitter suggest a widespread inability to appreciate other people’s subjectivities. Congregations of like-minded follower groups, where echo chambers of shared ideas objectify the identity of outsiders into catchall classifications—“Muslim extremists,” “Christians,” “liberals,” “conservatives”—don’t help, either. Will the Social Organism naturally evolve toward a more balanced and mutually beneficial set of relations? Or do we risk having it overrun by parasitic influences that skew the perspectives in their favor? Are empathy and a subject/subject system of sensory engagement part of its predestined progression, or will getting to that future require deliberate policy action? Is that even possible?

In chapter 6, we’ll discuss how social media can be used to inspire empathy through emotive words and images. My hope is that we can collectively help the Social Organism to evolve into what I’d like to see it become: a body of shared humanity that’s not only more creative, innovative, and prosperous but also more accepting of its own wondrous diversity. But before we discuss that meta-project, we must first delve more deeply into the workings of the Organism itself. It’s time to explore the memetic code.