CHAPTER SEVEN

CONFRONTING OUR PATHOGENS

Bolstering the Cultural Immune System

LIKE DARWINIAN evolution, the evolution of the Social Organism isn’t without pain and struggle. Europe’s ongoing refugee crisis, for instance, has unleashed xenophobia and brought out the worst of human reactions—again, played out in social media. This was encapsulated by the #wearefull hashtag that emerged in 2015 in Britain, a mutation of a more profane meme that appeared in Australia in association with that country’s draconian refugee policy: #FOWF for “Fuck off, we’re full.” It later fed into Britain’s massive and successful #Brexit campaign. Amid this vitriol, however, a single, heartbreaking photo had a dramatic sobering effect on public debate. Nilufur Demir’s photo of three-year-old Syrian boy Aylan Kurdi’s lifeless body lying facedown on a beach went viral on Facebook and Twitter.

In the days that followed, dozens of people staged a performance on a Moroccan beach, where they dressed in the same colored clothes of the boy and adopted the pose of his lifeless body in the sand. In both Gaza and India, giant sand castles were built in the shape and colors of Aylan’s body to pay tribute to the boy and appeal to people’s compassion for the fleeing refuges. Artists around the world began making poetic renderings of it, giving it an almost spiritual quality. These included a giant mural aligning Frankfurt’s Main River near the headquarters of the European Central Bank. It was one hell of a meme, joining the ranks of other iconic images of history—the naked girl fleeing napalm in Vietnam, the raising of the Stars & Stripes at Iwo Jima.

The greatest measure of the image’s power came shortly afterward, as there was a clear, discernible change in the public discourse. A Scottish tabloid began a campaign that spawned the #wehaveroom meme. In Germany, where the government decided to open the door to incoming refugees from Hungary, thousands turned up at entry points to cheer and welcome the new arrivals. German soccer fans displayed welcome banners, an unexpected gesture from a group more infamously known for their hooliganism. Images of signs at matches saying “Refugees Welcome!” spread on social media, leading some brands to seize a chance to show their social conscience. The soccer club Bayern Munich quickly announced a 1-million-euro donation to the refugees, and English clubs followed suit by creating a day of solidarity. It didn’t mean that the voices of exclusion such as France’s Marine Le Pen didn’t continue to milk people’s fears, especially after the Paris attacks. But it did mean that empathy was given a seat at the table when previously it had been denied one. In the ongoing cultural struggle in which opposing viewpoints do battle to determine which meme is fit enough to survive, this one made a powerful bid at inserting a lasting, positive mutation into our social DNA.

To unpack what we mean by a positive social mutation, we’ll first explore an example of a positive biological mutation. In this case, we’ll talk about one with a high-profile beneficiary: Timothy Ray Brown, the famous “Berlin patient,” the only known person to have been functionally cured of AIDS/HIV—distinguishing him from 10 million who live with the virus but have kept it dormant with expensive anti-retroviral drug therapy.

When Brown was treated for leukemia in 2007 he received a stem cell transplant bearing a unique genetic trait known as the CCR5 Delta-32 variant, an inherited feature that puts a protective seal over the carrier’s T-cell receptors and thus prevents HIV from finding an entry point into a host cell. Some 10 percent of people with European ancestry are believed to share this condition, but it is very rare among other populations.

The Delta-32 mutation has been passed down over centuries, and scientists are now researching its origins by analyzing human genetic history. At first it appeared to have originated with survivors of the bubonic plague. Now, scientists are zeroing in on a confluence of seminal epidemiological events over two millennia: the Roman conquests of Europe during the fifth-century BC, the great Plague of Athens in 430 BC, and the resistance that certain European populations showed smallpox scourges up to the eighteenth century. What we do know is that over the course of European history, ethnic intermingling helped spread this valuable genetic trait, and that it gained greater presence within inheritance lineages whenever devastating disease breakouts amped up the natural selection process. Only now, in this more scientifically advanced era, do we have the potential to replicate the helpful mutation and pass it on to anyone who needs it.

While it’s hard to imagine anything positive about HIV, smallpox, and Ebola outbreaks, scientists now know that viruses like these play a critical role in evolution. These maladies drive the mutation of genes, which in turn breeds resistance, much like that which the Delta-32 variant conferred on Timothy Brown. In fact, the human genome is riddled with genetic material from viruses that infected our ancestors. For example, blood tests of some AIDS patients, in whom HIV has disabled their immune system, have found traces of a reactivated virus that date back 6 million years to the time when humans and chimps first parted ways. Much as a software engineer might describe a less-than-perfect piece of computer code as “buggy,” we could say the same about our human DNA.

Our growing knowledge of the relationship between viral mutation and human evolution, and of how antigens and antibodies develop and evolve in tandem, is forging promising new disease treatments such as immunotherapy. By determining the causes and patterns of mutation in our genes and those of viruses, doctors can teach our immune systems new awareness and convert them into more effective defenders of our health. But there are also lessons in this process for understanding how the Social Organism undergoes cultural evolution via mutations in its memetic code. Recall rule seven: All living things adapt and evolve. If we want society to grow up, and if we want to turn social media into a constructive forum for improving human existence, then we must expose ourselves to the “diseases” of hate, intolerance, and intimidation that persist in our culture. It makes for a powerful case against censorship.

Many different measures show a dramatic improvement in the socializing tendencies of human beings since the rise of the Internet and social media in the early 1990s. While we can’t definitively prove that technology was the cause of these results, they do convincingly challenge the view among many that social media does great harm to society. Critics complain that people are now exposed 24/7 to displays of human conflict across a much less sanitized and more globalized media landscape than that of the pre–social media world. But that’s different from saying that society has become crueler. The evidence suggests quite the opposite has occurred.

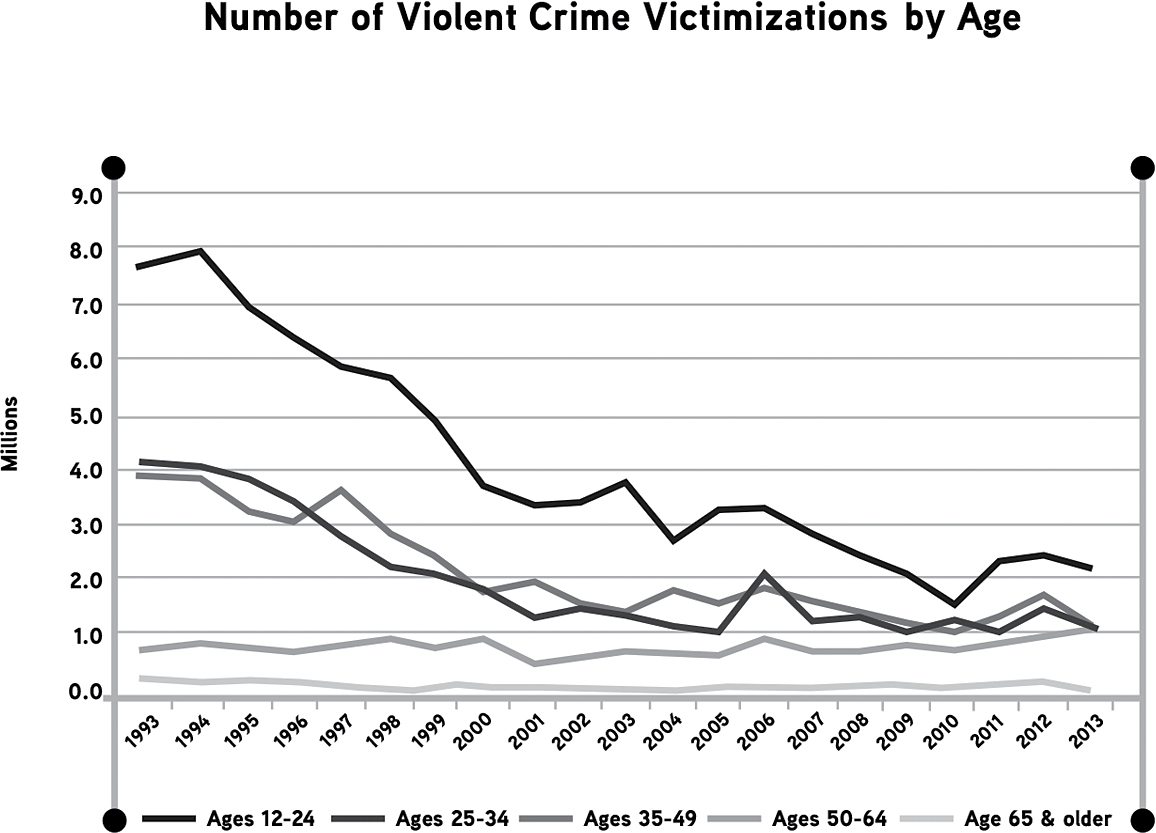

Crime statistics are a good place to start. Police, coronary, and hospital data across the Western world all show that a decline in violent crime accelerated after 1993, when the Internet first made inroads into mainstream society. Most strikingly, data in the United States show that violent crimes for people between the ages of twelve and twenty-four—the cohort that has traditionally suffered the most violence—more than halved in the twenty years that followed. This generation, of course, comprised the first digital natives, with their lives defined in sweeping ways by online activities.

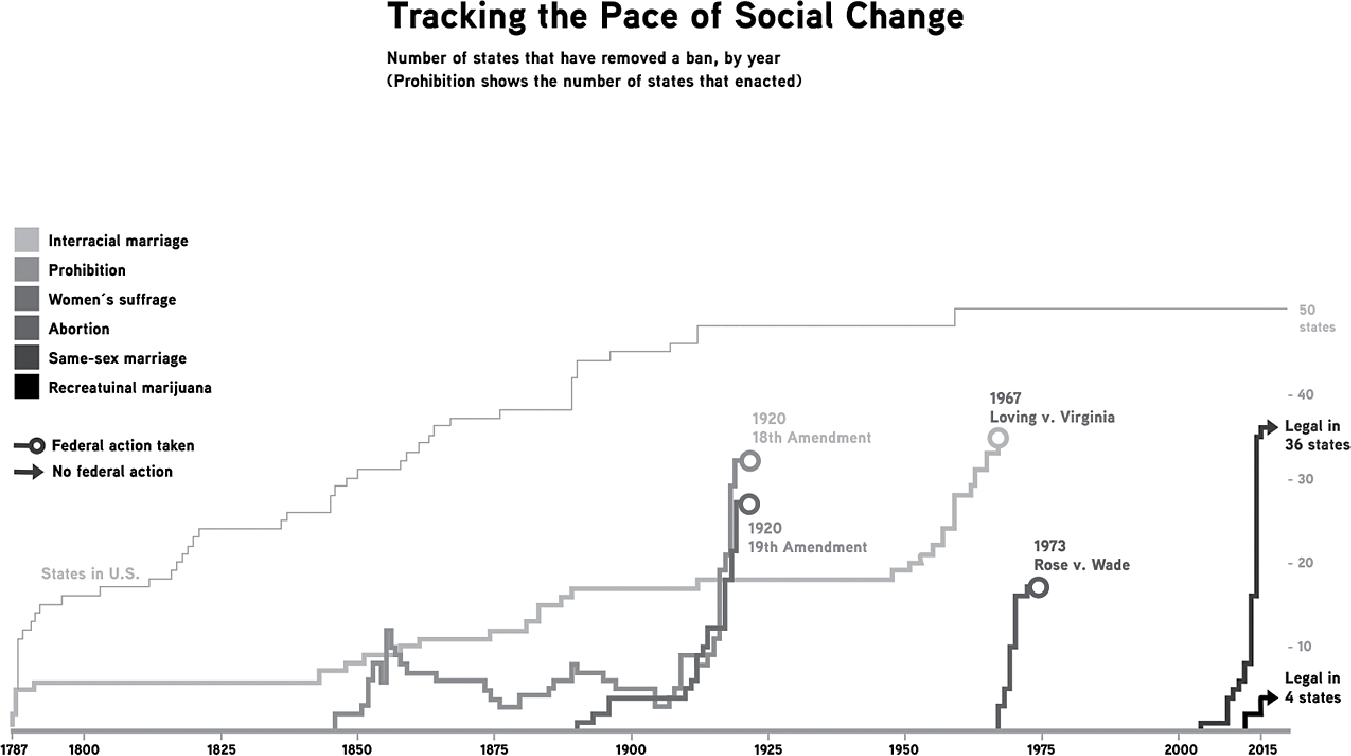

We see similarly striking evidence in Americans’ views surrounding race, religion, gender, and sexual preference. Attitudes toward marriage are a good barometer. The non-partisan Pew Research Center’s studies on same-sex marriage show that we’ve gone from only 35 percent in favor of such unions in 2001 to more than 55 percent in support by 2015. In that sense, the Supreme Court ruling legalizing same-sex marriage nationwide that same year was a case of the majority on its bench simply keeping up with society. Similarly, acceptance of interracial marriage has expanded rapidly, Pew results show: In 2012, two-thirds of Americans said they “would be fine” with a member of their family marrying someone of a different race. In 1986 the figure was only 33 percent. A more recent study of Millennials showed an even higher acceptance level, with nine in ten saying they’d be happy with a family member marrying outside their race.

Attitudes on such matters are changing at an accelerating pace. A 2015 Bloomberg graphic showed that on the legality of five key social questions—interracial marriage, women’s suffrage, prohibition, abortion, and same-sex marriage—the time between the first state to change its laws and the Supreme Court’s eventual validation of that position dramatically shortened over time. The article suggested that a similarly rapid shift was about to happen with support for legalizing recreational marijuana use.

Our culture is evolving at a faster pace, and that acceleration, we contend, is a function of the comingling of thoughts and memes—first on the Internet generally and now, more specifically, within social media. Despite the impression given by the warring factions on social media, we have become more tolerant, more inclusive.

We can view this trend toward greater social inclusion as an acceleration in the mutation rate for the Social Organism’s memetic code. Like the reproductive intermingling that imbedded the HIV-resistant CCR5 Delta-32 variant into some parts of the European population, this cultural change is encouraged by the interchange of ideas through memetic replication across the social organism. The process is incomplete, much as the spread of HIV-resistant genetic traits remains incomplete. But similarly to the role played by plagues and disease outbreaks, we can think of it as an evolutionary trend spurred by periods of epidemiological stress. These are the moments in which more highly evolved, inclusive ideas get most heavily tested and promoted through the machine of social media. We know that the strongest genes survive such stress tests; so, too, do the organism’s strongest memes. Those memes that best promote the growth and advancement of its heterogeneous, holarchic makeup will replicate, and thus rise to prominence. Ultimately, as the evidence suggests, this process favors ideas that further social inclusion.

Some readers, particularly those of a more conservative political bent, may dispute our socially liberal interpretation of these changes as a positive development. Religious groups will see the expansion of rights around sexual preferences as a regressive step. And whereas we see the diminishment of the Confederate flag’s presence in popular culture, cited at the outset of this book, as a progressive evolutionary leap, those who’ve held on to that symbol as a badge of Southern pride will see it as a retrograde move.

As we’ve stressed, evolution cannot be defined in moral terms. It doesn’t necessarily imply “better.” But it does typically mean stronger, more resistant to threats. From that perspective, we think there’s a scientific argument to be made that cultural evolution should tend toward greater inclusion. We can address it with some of the laws of physics and ecology that have dictated the algorithm of biological evolution over time. These tell us that if you widen the gene pool, for example, or expand the number of possible variables in a set of molecular reactions, you raise the chances of a stronger, more resilient form or strain emerging from the survival-of-the-fittest competition. Similarly, if we expand the array of cultural mores and ideas that are input into the Social Organism—if we widen the “meme pool”—we end up with a stronger, more resilient culture. Add to that the Social Organism’s natural instinct to grow, to expand, and you get a kind of mathematical logic calling for inclusion. Its antithesis, exclusion, goes directly against these instincts. This is why it is so alarming to see the rise of the Trumps, LePens, and movements like Brexit, which are all about building walls. Their approaches will narrow the pool of ideas.

It so happens that this fits with that long-held liberal intellectual tradition that defines history as a progressive march toward ever-greater individual liberty—from the absolute monarchies of feudal Europe to the Enlightenment to the Declaration of Independence to the civil rights movement. We can view this sequenced establishment of new freedoms as a record of society becoming progressively more accepting of difference. It’s a chronicle of how the powers that be have been compelled by changes in society, including those fueled by technology, to widen the boundaries of inclusion. There are retrograde phases in this process—some might argue that pervasive state surveillance in the Internet era represents one—but modern history has clearly moved along a continuum of great openness and acceptance. At each step, there has been a struggle between the old and the new. There is no free lunch. We may not need violent revolution to force change these days, but if we want to evolve, the conflict generated by exposure to raw content is inevitable.

Social media facilitates this movement toward inclusion, precisely because it compels us to pay witness to conflict in our midst. By opening ourselves up to an always-on, ubiquitously connected media environment, we are exposing our culture to more and more antigens. Whether it’s spam or hate messages, or the interjections of trolls, this otherwise ugly flow of antisocial communication is a necessary aspect of how we strengthen our immune system. Since we are only in the early days of this new reality, we are now going through the most difficult period in this process of cultural evolution. We have entered an unprecedented moment in the history of human socialization when the Organism has suddenly been exposed to a rash of different “diseases.”

One of the scariest aspects of these diseases has been the rise of a new breed of populist fascism. In this case, it’s a trend that readers on the more liberal side of the political aisle might use to counter our claim that social media is creating a more inclusive society. During the 2016 electoral campaign—still undecided at the time of writing—Donald Trump used his anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim rhetoric to bully his way to the Republican nomination and attract hordes of passionate supporters to rowdy rallies tinged with violence. This hardly looks like “progress.” But as Dartmouth professor Brendan Nyhan noted in a nineteen-part “tweetstorm” after a clash between Trump supporters and protestors in Chicago fueled concerns about the state of American democracy, statistics about American attitudes toward others—like those we cite above—do not support the notion that the egomaniacal failed businessman’s popularity reflects an overall rise in racial hatred. Rather, Nyhan argued, the Trump phenomenon stems from a failure of established political institutions to execute effective governance and balance out those destructive, exclusionary ideas that have always found a home in a large but otherwise disempowered minority of the population.

The old, vertical power structures in business, government, and mass media have been severely disrupted by our new communications paradigm, with its leaderless, holonic structure. As a result, their grip on power has waned, which is why they are proving to be impotent against an emotion-stirring personality cult like Trump’s. It’s also why UK political elites failed to dissuade a majority of Brits from voting with the “Leave” campaign, with its xenophobic undertones, when the “Brexit” referendum that they recklessly introduced on June 23, 2016 returned a decision that their country should depart the European Union. The big question is whether society can use the new media architecture, which follows the rules of biology more than those of Washington, to create a new system of mediation in place of those failed institutions. We think it can, and that the mechanism for doing so will come via the Social Organism’s evolutionary algorithm. It’s just that getting to that more comfortable, harmonious place is going to be a bit of a wild ride and will require thoughtful, open-minded policymaking along with pro-social civic action.

Is this social media moment in time the cultural equivalent of the black plague or whatever major historical epidemic gave rise to the CCR5 Delta-32 variant? Perhaps. The hope is that the accelerated rate of mutation set in motion by an unprecedented, worldwide memetic exchange will see us through this period of pain and discord relatively quickly. Already, people are learning what to do and what not to do on social media. The Social Organism is developing the antibodies it needs to survive.

Our bodies grow up stronger if we are exposed to more bacteria and viruses in childhood. When Michael and I were growing up, if word got out that someone in a school had chicken pox—a highly infectious disease that mostly just left kids covered in itchy scabs for a week or so—parents would bring their child to the home of the sick kid to deliberately expose them to the pox. The idea was that this would allow the child to create the antibodies early on to prevent them from ever catching it again. Given that it was far safer to catch this disease as a child than as a post-pubescent teen or adult—when the risk of more serious complications such as pneumonia or encephalitis is much higher—this seemingly reckless behavior was founded on sound reasoning, even if there were still some risks to your child’s health. Since 1995 there’s been a perfectly good chicken pox vaccine, offering a far safer way to build up the antibodies. Yet the concept of a vaccine, which of course is derived from the DNA of the threatening virus or bacteria, is based on the same core idea: Our genetic disposition is such that exposure to things that can ostensibly harm us also makes us stronger.

Unlike vaccines, which build up our immune system with antibodies so it can fight disease on its own, or immunotherapy, which effectively teaches that system to do the same, antibiotics are like an army of hired mercenaries. They directly attack infection-causing bacteria, killing these single-cell microorganisms on our behalf and preventing them from growing and reproducing. But once these mercenaries complete their job, they leave. They do not train the inhabitants of the previously occupied territory to fight on their own. What’s more, antibiotics have generally been unable to fight viruses, which are much smaller than bacteria and don’t have all of the features of full living organisms. (Recall that viruses are essentially just pieces of genetic material—either RNA or DNA—housed inside a molecule that can only replicate itself by entering the cell of a living organism and hijacking its internal reproductive machinery.) You can’t “kill” something that isn’t technically alive, which is why the only way to defeat a virus like the common cold is typically to wait for our immune system to figure out how to quell these constantly mutating diseases. But it also explains why the overuse of antibiotics poses a threat to public health. Like all living organisms, bacteria adapt and evolve, which means many are becoming resistant to antibiotics, a serious concern for the World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. So as important as antibiotics have been to saving lives ever since Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin, it turns out that it’s much better to teach our immune system to fight its pathogens—as it must do for viruses—than to rely on outsiders to do the work for it.

We can think of rules that curtail or censor antisocial speech, such as those that Twitter and Facebook are often being called upon to deploy, as a strategy akin to bringing in a disease-fighting mercenary service like an antibiotic. It might suppress the particular manifestation of the pathogen, but it won’t destroy the root DNA and the Social Organism won’t learn to fight back by itself. The memetic core of the offensive thought or idea—take, for example, the essential misogyny of the #Gamergate bigots—will live on and, with the aid of the cells that it has occupied (the supporters of that idea), it will fight back against this outside attack. Those supporters will, as they’ve always done, frame it as an attack on free speech. And, unfortunately, they will be right.

All social mores, the cultural norms that define who we are and how we interact with each other, have emerged out of these kinds of conflicts. In his book The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined, Steven Pinker cites sociologist Norbert Elias’s theory on the “civilizing process,” which deals with the development of social graces and etiquette, to explain how European society became more peaceable as it emerged from the Middle Ages. If you were invited to a banquet it was once commonplace to bring one’s own knife, an instrument that was used both for killing your enemies and for eating food. Gathered around the food, you would carve off a piece of the carcass and bring it to your mouth on the same knife. The problem with all these unsheathed knives around was that there was always a risk someone might get stabbed over a disagreement. This was not a comfortable situation for either the host or the guests, but violence was a part of everyday life in early medieval society; what was there to do about it?

The solution came in the evolution of table manners, which eventually dictated that it was unacceptable to use your personal knife to eat food, an idea that went hand in hand with that of cutlery. The fork was invented and special, less lethal knives were set at the table so that guests would not have to unsheathe theirs in the presence of others. Rules about the proper use of cutlery emerged, mostly concerned with what not to do with the table knife—don’t bring it to your mouth; don’t stir ingredients with your knife. What began as a practical solution to the dangers of provoking a knife fight evolved into a set of ingrained culture rules that happened also to keep conflicts at bay. Over time, these kinds of subtle shifts helped develop a value system that saw it as unacceptable to act violently in an ever wider array of arenas. In Pinker’s words, Elias’s research showed how “Europeans increasingly inhibited their impulses, anticipated the long-term consequences of their actions, and took other people’s thoughts and feelings into consideration. A culture of honor—the readiness to take revenge—gave way to a culture of dignity.” This was moral evolution at work.

As our interactions with each other change and migrate to digital spaces, we are forced to reassess our norms. Society then does what it has always done: It “polices” the newly unacceptable behavior, mostly by conveying disapproval, shaming the wrongdoer. Not only is this response aimed at changing that one person’s behavior; it also puts everyone else on notice that this is the new code. I think of it as a newly evolved immune response: Once the new antibodies are added to the immune system’s police force, it responds with as much clout as it can muster, both to beat off the foreign intruder and to lay protections against any future incursions.

With social media, we have radically expanded the potential for these kinds of value clashes to occur and, as a result, the transition period for cultural change has been dramatically shortened. In this new, borderless, global communications architecture we are experiencing an explosion of previously impossible cross-cultural interactions. These at first provoke conflict, which can only be resolved if there is some kind of collective cultural shift that redefines the boundaries of what’s acceptable. Just as important, once those new mores are established, social media provides a vast, open new platform for society’s immune system to do its police work. Think of this new online communion of human beings as a massive dinner table for hundreds of millions of interacting guests and for which a new etiquette must be developed. Dramatic, frequent changes in values are necessary if we are to avoid “killing” each other. Breaches of this newly established cultural order can inspire quite a powerful shock-like response as the Social Organism’s immune system kicks into gear.

Whether it’s cases like the Charleston massacre or the killing of Cecil the lion, the social media–driven purging response reminds me of a coagulation cascade, the biochemical reaction behind blood clotting that I found so fascinating as a teenage lab rat. When tissue is damaged and blood escapes, a synchronized dance of enzymes and metabolic factors occurs along the arachidonic acid pathway that leads to and from the site of the wound. This causes an army of tiny platelets to bind together, then, subsequently contract to contain the hemorrhage. To the body of the Social Organism, with its evolving culture, sometimes breaches in social harmony can seem like a deep wound that demands a similar response.

There’s another reason why cultural evolution is accelerating: We are now, in effect, crowdsourcing our mores. Etiquette and values were once dictated from above. In the Middle Ages, it was the aristocracy that led the way on table manners and the Church that told people what they could and couldn’t believe. Even in twentieth-century, pre–social media America, it wasn’t nearly as easy for those outside of the media and political establishment to argue for reforming social values. People could attend rallies, go on strike, and, if they had a way with words and access to a publisher, write a persuasive treatise. It was far better than nineteenth-century America, but it was nothing like what it is now, where with the mere click of a “like” or “retweet” button almost anyone can play a part in a movement that helps our culture evolve. Now it is the pool of society’s collective ideas, not the exclusive opinions of a priest or a CEO, that determines how we should behave toward one another. Sometimes the collective goes off kilter; other times it inspires progressive change.

Most people don’t grasp how this is happening. They see social media as something external to our culture, a distinct technology that can be isolated as a standalone phenomenon from the rest of our lives. They can’t see it for the driving force that it is: the primary engine of cultural disruption, a paradigm shift that’s changing us from within. Hashtag memes are still thought of as modes of expression that reside solely on social media, even though we are perpetually, if subconsciously, dragging them into the non-online world. The fact is that these memes and the stories that get attached to them are having a profound, far-reaching effect on our society generally, whether online or offline.

Let’s once again consider the #BlackLivesMatter movement, which I see as a form of immunotherapy. It is training society to develop the pattern recognition it needs to “see” the latent, institutionalized racism that continues to pose subtle but real barriers for black people. It forces us to recognize that this is a fundamental human rights issue. Yes, it has fostered an inevitable backlash from those whose ill-formed pattern recognition, shaped by a life of white privilege that they wrongly assume to be a universal experience, denies them the ability to comprehend the reality of black Americans’ lives. The first group sees what it believes to be a more-or-less non-discriminatory system; the latter knows that the state, in the form of armed policemen, systematically assigns less freedom of movement to their bodies than to those cloaked in white skin. This backlash engenders conflict and, in unpredictable ways that a leaderless movement like #BlackLivesMatter simply cannot control. We saw it in the summer of 2016 when the cities of Baton Rouge, Dallas, and Falcon Heights, Minnesota erupted in conflict amid the senseless loss of both black and “blue” lives. But while this conflict proceeds, so too does the evolution of our cultural immune system. #BlackLivesMatter has indeed shocked many whites out of their complacency. It is forcing all of us to see the different reality of others’ lives. It is creating a capacity for empathy that was until now sadly lacking.

It’s important to be clear about what we, in this context, mean by empathy—a critical emotional trait in the functioning of the Social Organism. Within individuals, scientists believe, empathy is both a learned behavior and genetically determined (people with Narcissistic Personality Disorder are thought to lack the empathy gene). Empathy is also a common element of the Social Organism’s shared culture. In that case, where the goal is to progressively update our memetic code and expand our culture’s empathetic reach across an ever-wider radius of living beings, the distinction between genetically acquired and learned empathy is moot. We should be constantly “teaching” our culture to be empathetic, and thus strengthening it, which is where the metaphor of immunotherapy is relevant.

Art, which has always played a fundamental role in getting people to recognize their common humanity, is as important as ever in this bid to foster empathy. I was exposed to its potential with a visit in 2106 to You Me Bum Bum Train in London, a unique theatrical experience in which you, as the sole audience member, become the central focus—the lead character, if you will—in a series of improvised scenes performed by over five hundred volunteer actors. From scenes of death, success, joy, humiliation, grieving, laughter, and exhilaration, the creators take you on a bizarre journey to reveal the deep human capacity for empathy. It was truly a life-changing experience for me. Of course, the social impact is limited for a privileged, one-person audience. The challenge—and the opportunity—that artists face is to use the tools of social media to have this kind of effect on a giant, global audience.

It’s not hard to imagine how social media could help expand empathy. It offers powerful tools for content providers to help people see the world through the eyes of millions of others every day. In fact, I think cultural immunotherapies will only become more powerful as virtual reality tools improve, creating something we might call “VR empathy generators.” Imagine social media–connected people, plugged in with cameras and unimposing viewing goggles, connecting vividly with strangers in their moments of suffering or joy, something we were previously unable or unwilling to do—a kind of You Me Bum Bum Train for everyone. We’re not there yet, but we are moving in that direction. The sweeping social impact of smartphone-shot videos of black men and women being mistreated by police are an early manifestation of this potential.

Those captured moments of “citizen journalism” and the powerful proofs they provided of an injustice previously hidden to white Americans, helped turn #BlackLivesMatter into a sweeping social project. As replicated messages traveled widely and rapidly across influencer networks, the hashtag meme—and the movement that it spawned—was empowered to change the Social Organism’s overall memetic makeup. #BlackLivesMatter became an all-present mantra, imbedding itself into our collective consciousness. And from there, the model was transferred to broader society, including into the offline world, thus extending the effect of the immunotherapeutic treatment. Racism has always been one of our most resilient and harmful diseases; #BlackLivesMatter is shocking our immune system into recognizing it and fighting it.

The #BLM movement has experienced rapid growth requiring the development and appointment of identifiable leaders. As of July 2016, there were thirty-eight chapters in the United States and Canada. Indeed, a decidedly real-world organizational structure has emerged out of what was initially an organic, spontaneous call for justice—albeit a structure that is still far more horizontal, decentralized, and holarchic than political organizations of the past. In a far-sighted definition of what it means in these changing times to call something a “company,” Fast Company ranked #BlackLivesMatter number nine in its list of the fifty most innovative companies of 2016. An article on CNN Interactive that identified some of #BLM’s main players used a Silicon Valley–like phrase to describe them in its title: “The Disruptors.”

In the previous chapter we talked about how we could use new data-gathering techniques to map and learn more about what kinds of content triggers immediate responses in the Organism. In a similar vein, might we also be able to map and study how it evolves? Put differently, can we sequence the human memetic code? It wouldn’t be the first time people have tried to do so.

In 2003, Nova Spivack, an entrepreneur, venture capitalist, and leading thinker in Big Data, artificial intelligence, and Web semantics, launched what he called “The Human Menome Project.” (The name was an obvious play on the publicly funded Human Genome Project, which that same year completed its sequencing of the human genome, three years behind a private initiative by Craig Venter’s Celera Corporation.) On his blog, Spivack proposed that to compute the “Menome of humanity” in real time, we should “mine the Web for noun-phrases and then measure the space-time dynamics of those phrases as they move through various demographic, geographic, and topical spaces.” The end result would be a “set of the most influential memes presently active around the world” as well as a record of “the menomes of individual societies, demographic groups, communities, etc.”

Another initiative, calling itself the Human Memome Project (with an “m”), was launched a few years later by the Center for Human Emergence, a group led by Don Edward Beck, the inventor of the “spiral dynamics” complex modeling method for studying the evolutionary development of large-scale human psychology. Beck, who labels his method “the theory that explains everything,” counts as his influences Richard Dawkins and the development psychologist Clare W. Graves. On its website, the Human Memome Project’s goal is described as to “create a synthesis of all of the various viewpoints on cultural transformation, societal change, the nature of conflict, forms of conflict prevention, and development, in order to generate sophisticated electronic maps designed to monitor, at the deepest level, waves of chaos and order, change and stability, and progress and regression within our collective selves.”

The outcome of these projects is not yet clear, but both efforts suggest that as Big Data techniques deepen our understandings of how complex systems evolve, people will increasingly try to identify some kind of “essence” of our nature as social beings. There’s a scientific will to find the cultural equivalent of the genome, now viewed as the almost definitive blueprint of our biological selves. It’s as if we’re cranking up a super computer in search of the human soul.

If we do complete the equivalent of the Human Genome Project and sequence the menome, what might we find?* What confrontations with “disease” in our society’s past have helped our culture build up antibodies to social division? Does the capacity for many of us—hopefully most of us—to recognize and resist the fascist signals of an egomaniacal present-day politician trace its origins to the painful European conflicts of the 1930s and 1940s? Among the countless painful “epidemic episodes” that helped our society evolve, we’d perhaps find: 1960s images of lynchings and bombed churches that moved white Americans to join their black compatriots in support of civil rights; the heartache of the Vietnam War that led people to question the once common sentiment of “my country, right or wrong”; the brutal murder of Matthew Shepard in Laramie, Wyoming, which helped galvanize empathy for the lonely struggle of oppressed gay youth. We’d also find positive moments that created lasting, memorable memes that continue to embolden us to stand up for what’s right: Martin Luther King’s speeches, the stories of brave defiant figures like Anne Frank, heroic figures from wars and other tragedies like the firefighters who died saving thousands on September 11, not to mention uplifting moments that celebrate genius in the arts and science, whether it’s Mozart’s Requiem or the Wright Brothers’ Kitty Hawk taking flight. Think, for example, of how deeply this phrase runs in our collective psyche’s sense of human potential: “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” All these past moments of both failure and victory have informed our sense of what it means to belong to the communion of human life. They forge a collective pool of empathy from which we all draw.

So, the question is: What would have happened if we’d blocked those memes? What if Hitler’s genocidal campaign was never exposed to the outside world? What if Martin Luther King Jr. had been barred from taking his place at the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, so that the words “I have a dream” were only heard by a few of his close confidants? Undoubtedly our culture would not have progressed as far as it has. If we hadn’t developed the antibodies, we’d be even more vulnerable to racism and intolerance than we currently are. And that would not only hold us back morally but also economically.

This is all very well, but what are we to do with this knowledge? If there’s no turning back from social media, how can we work with that system to steer the Social Organism into a healthier state? Well, I think we’ve got some great ideas. Read on.