INTRODUCTION

Epiphany in the Desert

The Seven Rules of Life in Social Media

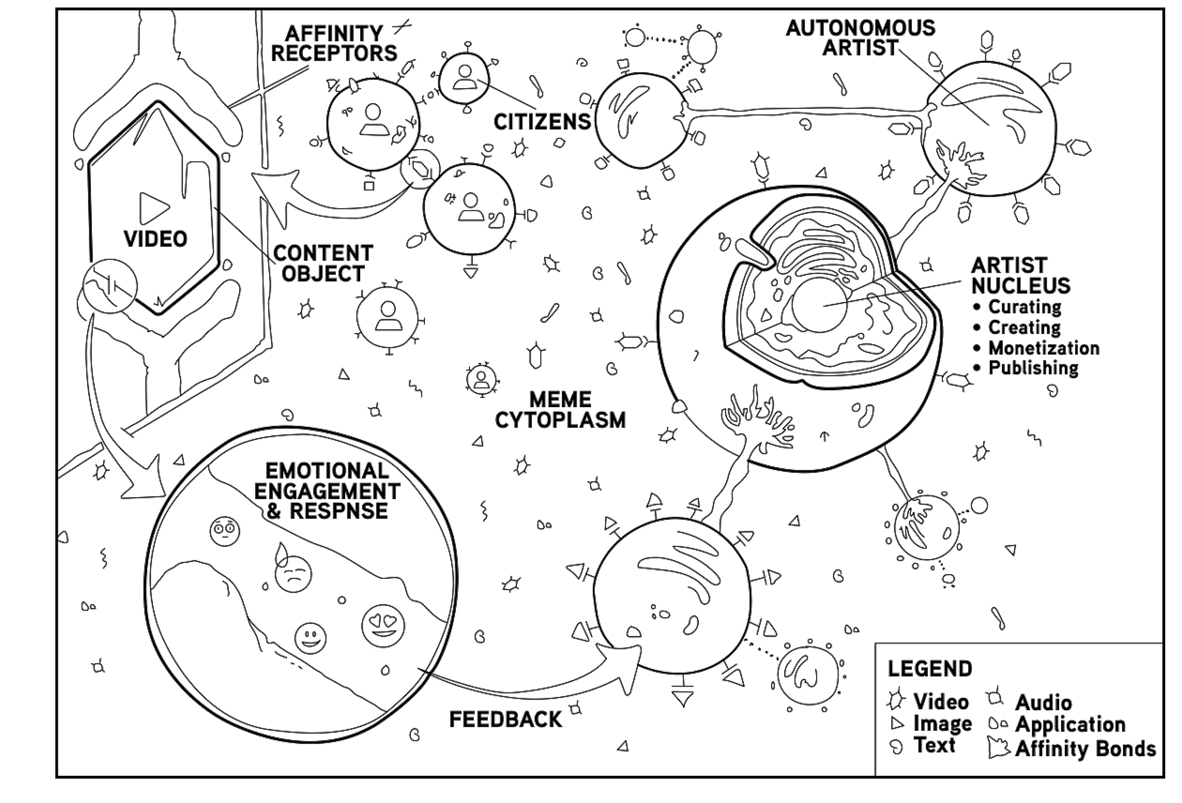

In March 2013, my boyfriend Scott and I traveled from our Los Angeles home to Joshua Tree National Park for our yearly digital detox and fasting retreat at a quirky spa called WeCare, a sanctuary we lovingly call Colon Camp. As in times past, we needed a break desperately. Details had recently bestowed a few entrepreneurs, including me, with the cringe-worthy title of “Digital Maverick,” tasking us with drawing a graphic representation of the “future of social media.” I wanted to provide the magazine with a thought-provoking image, and, as we began our retreat, I felt bothered that I hadn’t yet conceived of an illustration that would adequately capture the immense if amorphous technological sea change happening before our eyes. What were the analogies? How could I map the interconnectedness of social media users?

I’ve always been a visual person with a deep love of patterns and art. But as I walked out into the desert each morning and thought of all the flow charts I’d drafted since my first digital world job at Qwest Communications two decades ago, I remained stumped. None of those stacked-up, tree-like diagrams of the first IP-telephone systems captured the nuances of the human beings connected to each other, nor did they explain the complexities of the like, the share, the retweet. My mind drifted further back into the past—to drawings from the hematology lab in which I’d worked during high school. I’d been obsessed with microbiology and had memorized the colorful images of the cascading metabolic actions that described the pathway from “cut to closure” during coagulation. The evolved system of thrombocyte factors, platelets, the shape-shifting non-nucleated megakaryocytes, and the incredible spider-like glue of fibrin had captured my imagination. As a sixteen-year-old at the International Science and Engineering Fair at Disney’s Epcot Center, I won second place in the world for my work on “Further Characterization of Glycoprotein IIb-IIIA, the major Fibrinogen Receptor on the Human Platelet.” Yup, I was that nerdy kid.

Since high school I’d let my knowledge of biological phenomena wane. After enrolling in summer courses in human physiology, marine biology, and molecular biology at Harvard, I’d discovered my love of weed, which helped ease my mind and synthesize my racing and rampant ADHD. At Vanderbilt, a university known for its rich cultural heritage and literature programs, I took another detour from the study of biology. I finished my major in French Renaissance literature, and became obsessed with how the Catholic Church had built and then lost its hold on information, how the Gutenberg printing press and the introduction of kindergarten forged a literate middle class, and how this all led to the twentieth-century notion of mass media into which I was born. Inspired by the music of the Talking Heads and the subversive ideas of Neil Postman, Theodore Roszak, James Twitchell, and the Berkeley counterculture movement of the sixties, I also developed a disdain for the new breed of corporate controllers.

Surveying the desert, I felt the disconnect between my life then and now was as vast as the landscape before me. I’d gone from being a closeted, Mississippi-born, nature-loving geek to sitting at the helm of a glitzy media company that I had cofounded with two of Hollywood’s most colorful characters, a service that links hundreds of top-name celebrities with hundreds of millions of interconnected souls. But suddenly, in my food-deprived state, the bridge between them became clear in one of those all-too-rare bolts of insight. The knowledge I’d stored from the biology lab and my study of communication history suddenly coalesced, and, whoosh, a colorful image of the microscopic environments of cells and viruses that I’d seen in petri dishes rushed into my head. That was it! Social media was mimicking an organism. Our communication network had evolved into a living, “breathing” creature, one from which I was now deriving a livelihood. If it was a living organism, I reasoned, the rules of life should apply. I, a lab-rat-turned-“Digital Maverick,” was just one of billions of differentiated cells inside this same organism. We are its cells and our interconnected, timeless, and ubiquitous Internet networks are the substrate for this new life form.*

Was this just a trippy, reductionist metaphor conceived under the duress of too much heat and not enough food? For the weeks and months that followed, I kicked the tires on the comparison between social media and biology, running it through all sorts of scenarios. And when I applied it to the work I’d been doing at theAudience—the company I’d founded three years earlier with Hollywood talent mogul Ari Emanuel and Napster founder Sean Parker—the metaphor seemed ever more apt. Our publishing outfit at theAudience was tapping into an ecosystem in which artists, brands, events, and fans all thrived because of the organic connections they enjoyed through a network of influencers that reaches more than a billion customers a month. The content we were pushing out was specifically designed to find the patterns and latch on to the human “cells” that make up those networks. These would then replicate it in a manner akin to how a biological virus will exploit a biological human cell’s internal machinery to spread itself through a process of auto-replication. It was not for nothing that we boasted of having found the formula for making content and ideas go viral.

As I explored the metaphor further, I began to think of the world’s social media users as 1.5 billion autonomous organisms, attached through the emotion-sharing machines in our hands, forging a connection that transcends time and distance. The sum of these parts, all of us fluidly interacting together, was the singular Social Organism, a ubiquitous life form that was constantly nourishing itself, growing, and evolving. In sharing and replicating packets of information as memes (e.g., sharing a video on Facebook), we—the cells of the organism—are facilitating an evolutionary process much like the transfer of genetic information in and among living things.

Soon, I was seeing the entire social media environment through this new lens. The most effective social media communication, including the #BlackLivesMatter and #TakeItDown hashtags, were transformative memes, building blocks of our evolving cultural DNA. (This connection between memes and genes is drawn from the ideas of Richard Dawkins, who first introduced the word “meme” to the lexicon in 1976.)

For several years now, the biological word “viral” has come to denote a phenomenon where online content is widely shared or viewed. In the Social Organism concept, I discovered new dimensions to this parallel concept. A biological virus will seek out receptors on the outer membrane of cells so that one might let it enter its cytoplasm. Once inside, the virus adds information to start altering the cell’s DNA. That process provokes genetic mutation, a phenomenon that for the most part goes unnoticed inside our bodies. The result can sometimes be disease, but in time a viral attack can also create new resiliencies and contribute to biological evolution. Similarly, I realized, viral media content attaches itself to what I now call our personal affinity receptors. Once inside the human “cell” on the network, this appealing content slowly starts to alter the memetic code that shapes our thinking. Often the effects are inconsequential (the sharing of a silly cat video engenders a laugh and perhaps a desire to see more cat videos) or positive; sometimes they are grave, disease-like, and even a threat to the wider Social Organism (e.g., ISIS’s use of social media to call others to violent acts).

As social media has grown, it has evolved into a profoundly complex organism, as if going from a simple life form such as an amoeba to the complexity of a multi-cell organism like the human body. The activity of this increasingly expanding network of interacting human beings began with a mostly static set of actions—sending an email, for example. It later incorporated more interactive engagements such as blog posts, which could be read by a much wider array of readers. Now, social media activity encapsulates a mind-boggling array of inter-relationships. In this new, more highly evolved organism, a single YouTube video can be shared a million times and, in turn, inspire countless derivative knock-offs, parodies, homage videos, memes, hashtags, and conversations, all collectively pushing the original work’s cultural influence ever further and wider. This flow of auto-subdividing information can simultaneously flow outward to reach a wider audience but also behave recursively, turning back on its origins in a self-adjusting, self-corrective inflow of new ideas. It’s impossible for us to map these innumerable interactions, reactions, and counter-reactions in our heads; they defy the linear, causal explanations that our brains feel inclined to seek, leaving us overwhelmed with information. But just as powerful computers now let scientists study the once impenetrably complex features of the human body, so, too, are tools emerging, mostly in the field of Big Data analytics, to investigate the workings of the Social Organism.

That work, especially the graphical illustrations that data analytics have generated around social media, helped reinforce the parallels with microbiology that I’d recognized in that revelatory moment at the Joshua Tree National Park. As such, I came to see that if we follow how biological pathways work, we could learn how to manage this unruly new organic media architecture. There was by now no doubt in my mind about the picture I would submit to Details:

Remember high school biology? For me that was where my journey began. I was a rambunctious kid, but, thankfully, my AP biology teacher, Mrs. Franceschetti, saw something in me. (In a Facebook exchange, she recently described me as “the wildest but most intelligent student I ever had.”) Mrs. Franceschetti arranged for me to work several half-days each school week at the Lisa K. Jennings Hematology lab at the University of Tennessee Hospital. It was awesome.

One of the first things anyone learns in biology class is that life has seven essential characteristics, a set of clear, essential rules that distinguish living things from their inanimate counterparts in the material world.

Here’s a refresher:

1. Cellular structure. Living things are organized around cells. They can be simple, single-cell amoebas or occupy something as complex as the human body, home to trillions of different cells organized into specialized roles.

2. Metabolism. Living things need nourishment, for which their metabolism converts chemicals (nutrients) and energy into cellular matter while producing decomposing organic matter as a byproduct. Put simply, living things need food and purge themselves of waste.

3. Growth and complexity: In producing more cellular matter than organic waste, living things grow over time and become more complex.

4. Homeostasis: Organisms regulate their internal environment, taking actions to keep it in a balanced, stable state.

5. Responses to stimuli: Living things respond to changes in their external environment, instituting alterations to their makeup or behavior to protect themselves.

6. Reproduction: Living things produce offspring.

7. Adaption/Evolution: Living organisms adapt to lasting changes in their environment. And over the long term, by transferring survivor genes to their offspring, they evolve.

Since that trip to the desert in 2013, I’ve tested these seven rules and how they relate to what we see going on in our culture and in social media and retroactively applied them to what I saw in my past work, from Disney Co. to theAudience. I sometimes describe my career as a climb up the so-called OSI network stack, from fiber and wavelengths to data systems to applications to social networks, and from there to the content that lives on top of those networks and, ultimately, to the people behind the creative output. Having seen what types of marketing, viral sensations, and publicity efforts succeeded and failed in those settings, I was convinced the seven rules apply almost as readily to social media as to biology.

Consider rule number one: a cell structure. Billions of emotion-driven human actors comprise the cells of our Social Organism. Just like the organizational structure of other complex cellular organisms, mostly notably the human body, as well as that of other community-like natural phenomena such as hives of bees or ants, the cells of the Social Organism form a holarchy. Each human unit on the network constitutes what Austrian intellectual Arthur Koestler described as a holon, meaning that it is both independent and part of a wider whole; its activity is autonomous but at the same time simultaneously limited by and dictating the rules and activity of the greater group.

This community of cells devours a constant feed of quips, comments, selfies, articles, and new ideas, all digitally conveyed in text, images, and video. Thus we can view content uploaded into these systems as its nourishment. As it feeds the Social Organism becomes larger and more complex in its intercellular connections and network reach. Here we come to rules two and three. The organism’s metabolism of human emotional response processes the content, absorbing, sharing, and reshaping it to allow growth. Meanwhile, it purges itself of waste—all the unloved content that fails to achieve mass reach, the billions of tweets that get lost in the ether, the YouTube posts that wither with a view count in the double digits, and the rule-breaking social media users who are expunged from the system by pitchforked vigilantes. What fate befalls a particular piece of content or cellular node depends on whether the Social Organism regards it as healthy nourishment. Having observed the mistakes and successes of content creators from within and outside the media establishment, I’ve learned what types of content nourish a social media network—getting absorbed and replicated—and which do not. We’ll explore these ideas in the pages ahead.

The fourth rule on homeostasis—that living things regulate their internal environments to maintain balance—brings us to the concept of metabolic pathways. In a biological organism, this refers to the chemical reaction chains along which molecular components coordinate actions within and across cells. They are the communication lines of cells and, if broken, different parts of the system won’t know what the others are doing; homeostasis will fail—the organism’s internal temperature will rise too fast on a hot day, or its acidity levels will blow out when a certain food is eaten. Think of what happens when the limb of a tree is damaged: Branches and leaves beyond that point can’t receive the water and nutrients needed to regulate photosynthesis, so they wither and die. So, too, in social media, the lines of communication for emotional exchange must stay open. Otherwise there is no capacity for equilibrium. The system can’t tolerate that.

This is not a position that today’s online message managers always feel comfortable with. The first instinct of brand builders for public figures, top companies, and artists is often to cut off information flow to maintain proprietorial control and “exclusivity” of the information. It’s the wrong choice. I’ve seen successful, profitable content suddenly lose momentum when the lines are shut, or when, God forbid, you publish it exclusively to Jay-Z’s TIDAL service. Biology’s rules tell us that managers of information (and copyright)—be they artists, journalists, advertisers, marketing managers, corporate publishers, or governments—need to be far more laissez-faire in their approach if they want to reach and connect with people.

To illustrate rule number five, the organism’s response to outside stimuli, let us return to the Charleston massacre. To many, especially black Americans, the killings and Dylann Roof’s photos were untenable. As such the overall community of social media, which at its widest encapsulates the full array of America’s diverse, multiracial society, could no longer abide such a symbol of intolerance and division as the Confederate flag. I see Charleston as an example of how periodic hashtag “movements” serve as a kind of immune system response. They are the irritants, the antigens that elicit an emotional and functional response to fight against attacks from perceived pathogens.

With the sixth and seventh rules—reproduction and adaption/evolution—we witness the Social Organism’s lasting impact in our culture. Memes—those vessels of culture-shaping information that comprise our social DNA—give rise to other memes and ideas through a process of reproduction. Meanwhile, the organism faces constant conflict, as the ideas propagated by new memes often prompt a backlash from people who hold countering views. But just as our bodies are made stronger by exposure to bacteria, conflict is necessary for the organism to adapt and evolve. The open petri dish of our noisy, uncensored world of social media—as jarring and alarming as it can be—is now the main driver of cultural evolution.

Evolution is not perfect. This process doesn’t always result in “progress”—at least not as that word would be defined by liberals. Even as humans can communicate across vast geographic gaps like never before, differing values persist across the human spectrum and a consensus will often seem hard to find. With social media, both extreme progressives and extreme conservatives now have a megaphone previously denied them by centrally controlled media. Either side can emerge triumphant in a given conflict, depending on the message and context. This constant clash is consistent with the complexity of biological life, where conflict between and within organisms is a feature of existence. The cell structures of living things are just as capable of playing host to forces of sickness and death as they are of facilitating growth and life. Cancers thrive within the human body, sometimes overwhelming the immune system, other times not. Viruses are constantly penetrating cells and tricking their genetic DNA into allowing them to replicate themselves. But here’s the good news: The daily battles in which our immune systems engage will over time give rise to important changes. In the genetic mutations provoked by viruses and disease, lasting strength is derived. These challenges are how species adapt and evolve. The same goes for the Social Organism and the human culture that emerges from it.

With my metaphor and seven rules in hand, I had the courage to begin speaking publicly about this thesis. I had always been on the business speaker circuit but had grown tired of talking about celebrities or my business, so I started throwing these ideas around. I was shocked by the overwhelmingly positive response I was getting. I realized it was time to bring the broad implications of these sweeping changes to a wide audience. I needed a collaborator with a strong grasp of how ideas spread and how network technologies and global connections can disrupt old hierarchies of power. So, I was incredibly lucky to stumble across Michael Casey at an entrepreneurs’ summit to discuss bitcoin at Richard Branson’s Necker Island. Here was a unique case: a recognized, serious business journalist who had also written a seminal work about the iconic image of Che Guevara, perhaps one of our most pervasive modern cultural memes, in addition to books about global economics and the blockchain—the revolutionary peer-to-peer technology behind bitcoin. Michael and I had a true meeting of minds over my concept of the Social Organism and we shared a healthy sarcasm and humor. In that Caribbean paradise, a partnership was formed.

Together, in this book Michael and I will seek not only to illuminate the organic nature of a rapidly changing media environment but also provide tools for succeeding within it. Everyone, from CEOs to military leaders to kindergarten teachers, needs to understand how the Social Organism functions. If we fail to do so, the risks are great. The lessons we’ll draw from the behavior of molecules, metabolic pathways, enzymes, biochemical reactions, and genes are vital for politicians, activists, businesses, and any other individual or organization seeking to develop a corporate or personal digital persona or brand. Successful marketing strategies over this new communication architecture require us to determine how to connect emotionally with the people who function as its messengers—the artists and influencers around whom the network organically forms. There are lessons for educators, who will find that social media is becoming an increasingly important mechanism for knowledge transfer and that our top-down education system is fundamentally unsuitable to prepare children for this new world. There are also important takeaways for business managers, since the diffuse relationships of social media have rendered obsolete the hierarchical command lines of twentieth-century organizational theory. Most important, with this book I want to encourage the world’s future artists, leaders, and communicators to present their “memetic differences” and have confidence in social media platforms so that they can build lasting direct-to-consumer relationships and shut out the gatekeepers who still wield too much control over our lives.

This change in mind-set is necessary because this particular evolutionary step, the one that brought us to this new, biological communications model, is the societal equivalent of those dramatic shifts in the evolution of the living world. It calls for metaphors such as those moments when living organisms first crawled out of the Cambrian swamps or when our hominid ancestors first came down from the trees.

For thousands of years before this change, information was delivered via a top-down model. Those who controlled it were powerful, centralized organizations, whether it was the church, a broadcaster, or a newspaper. Each was beholden to an editorial hierarchy that determined what messages were distributed by physical equipment that included printing presses and communications towers. Under that model, a chain of command initiated by a person of authority such as the CEO would convey standing instructions for teams of employees and their equipment to follow a preordained plan for distributing the material—be it a newspaper or a broadcast news report. In contrast, today’s mass media infrastructure is defined by untethered devices connected via a decentralized, less predictable, and far more organic structure. Its distribution network is not comprised of hardware or workers beholden to their bosses’ orders but of more than a billion autonomous brains. These brains are linked through personal digital connections that defy both time and distance and which in turn form cognitive and emotional pathways. Each brain functions as a kind of biological switching technology. Collectively, it is these autonomous units—not the CEO or editor-in-chief—that determine which messages the crowd gets to hear and which get buried.

Within this network of neurons and synapses, ideas such as those encapsulated in catchy hashtags or poignant GIFs can be very rapidly disseminated across wide distances. These neatly distilled vessels of thought resonate emotionally with others, who in turn share, re-share, alter, and replicate them across ever-wider circles of influence. The ideas that stick become instrumental memes that form what I regard as our social DNA, the coded building blocks upon which our culture evolves. The most powerful of them are calls to action that tap into events unfolding in real time, creating a sense of urgency. But they also build on top of prior ideas, our social stored memory of the past. Meme by meme, we are building a cultural framework of meaning, one that is constantly iterated, reformed, and recorded in a digital trail of social interaction. Human society has not seen anything like this before.

Michael and I will make the case that social media represents the most advanced state yet in the evolution of human communication—and in the next two chapters we’ll chart how we arrived at this pivotal moment. One thing I will not do in this book is argue that social media is perfect. There is no guarantee that it will continue to develop in a way that benefits society. Already, the new players who dominate the network platforms are taking steps to control and censor information—moves detrimental to the Social Organism’s development and to the objective of an open, vibrant society. In doing this, these new gatekeepers harm their own market, of course—evident in the fact that Millennials are abandoning Facebook while Generation Z is gravitating toward Snapchat and other platforms that give them more freedom and control. That self-correcting, homeostatic mechanism could be the means through which social media moves to a more decentralized structure. Other decentralizing technologies could accelerate that process. Even so, companies like Facebook, Twitter, and Google have amassed enormous control over our lives—so much so that they now rank alongside the governments of China and India as the biggest managers of people’s identities in the world. If they are to have such power, it is critical that their platforms be opened up to a freer flow of information and that their infrastructure and algorithms be transparent. It’s also incumbent upon us to be aware and vote with our feet to ensure that happens.

The ground has shifted beneath us. The future of social media should be one of humanity’s dominant concerns. In barely a decade, the form has positioned itself at the center of twenty-first-century society. In this new world, everything from interpersonal relationships to marketing to corporate and political structures is being upended. How do we exist within this new reality? We struggle to keep up, at best. We’re at once obsessed and horrified by this new phenomenon. We try to describe it in reductionist ways, but end up with a host of competing metaphors: social media as a marketing tool, as a forum for jokester Millennials to pit their wit against each other, as a way to maintain human bonds with distant friends and family, or as a giant, noisy town square full of half-crazed people yelling libelous abuse at each other. But none of them come close to capturing it in its complex entirety. So we just stay confused.

We need to operate confidently within social media, not simply hang on to the edges while it hurtles forward. But to do that, we must first understand it. We need a guide, one with a frame of reference that ties this seemingly unfamiliar, uncharted new concept to a field of inquiry that’s far more deeply established and recognized. Biology, the study of life itself, is that reference.