Commerce and Coalitions: How Trade Affects Domestic Political Alignments

According to the Stolper-Samuelson theorem, free trade benefits locally abundant factors of production—such as land, labor, or capital—and harms locally scarce factors of production. Building on this insight, Ronald Rogowski offers a compelling theoretical and empirical account of political cleavages within countries. He extends the Stolper-Samuelson theorem to reason that increasing exposure to trade—say, because of falling transportation costs—will increase the political power of locally abundant factors, whereas decreasing exposure to trade will hurt these factors. Although not seeking to explain trade policy outcomes (such as the level of protection within a country), Rogowski provides a powerful explanation of the political coalitions and the politics surrounding trade policy. This essay shows how international economic forces can exert a profound effect on domestic politics.

THE STOLPER-SAMUELSON THEOREM

In 1941, Wolfgang Stolper and Paul Samuelson solved conclusively the old riddle of gains and losses from protection (or, for that matter, from free trade). In almost any society, they showed, protection benefits (and liberalization of trade harms) owners of factors in which, relative to the rest of the world, that society is poorly endowed, as well as producers who use that scarce factor intensively. Conversely, protection harms (and liberalization benefits) those factors that—again, relative to the rest of the world—the given society holds abundantly, and the producers who use those locally abundant factors intensively. Thus, in a society rich in labor but poor in capital, protection benefits capital and harms labor; and liberalization of trade benefits labor and harms capital.

So far, the theorem is what it is usually perceived to be, merely a statement, albeit an important and sweeping one, about the effects of tariff policy. The picture is altered, however, when one realizes that exogenous changes can have exactly the same effects as increases or decreases in protection. A cheapening of transport costs, for example, is indistinguishable in its act from an across-the-board decrease in every affected state’s tariffs; so is any change in the international regime that decreases the risks or the transaction costs of trade. The converse is of course equally true: when a nation’s external transport becomes dearer or its trade less secure, it is affected exactly as if it had imposed a higher tariff.

The point is of more than academic interest because we know, historically, that major changes in the risks and costs of international trade have occurred: notoriously, the railroads and steamships of the nineteenth century brought drastically cheaper transportation; so, in their day, did the improvements in shipbuilding and navigation of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries; and so, in our own generation, have supertankers, cheap oil, and containerization. According to the familiar argument,… international hegemony decreases both the risks and the transaction costs of international trade; and the decline of hegemonic power makes trade more expensive, perhaps—as, some have argued, in the 1930s—prohibitively so….

Global changes of these kinds, it follows, should have had global consequences. The “transportation revolutions” of the sixteenth, the nineteenth, and scarcely less of the mid-twentieth century must have benefited in each affected country owners and intensive employers of locally abundant factors and must have harmed owners and intensive employers of locally scarce factors. The events of the 1930s should have had exactly the opposite effect. What, however, will have been the political consequences of those shifts of wealth and income? To answer that question, we require a rudimentary model of the political process and a somewhat more definite one of the economy.

SIMPLE MODELS OF THE POLITY AND THE ECONOMY

Concerning domestic political processes, I shall make only three assumptions: that the beneficiaries of a change will try to continue and accelerate it, while the victims of the same change will endeavor to retard or halt it; that those who enjoy a sudden increase in wealth and income will thereby be enabled to expand their political influence as well; and that, as the desire and the means for a particular political preference increase, the likelihood grows that political entrepreneurs will devise mechanisms that can surmount the obstacles to collective action.

For our present concerns, the first assumption implies that the beneficiaries of safer or cheaper trade will support yet greater openness, while gainers from dearer or riskier trade will pursue even greater self-sufficiency. Conversely, those who are harmed by easier trade will demand protection or imperialism; and the victims of exogenously induced constrictions of trade will seek offsetting reductions in barriers. More important, the second assumption implies that the beneficiaries, potential or actual, of any such exogenous change will be strengthened politically (although they may still lose); the economic losers will be weakened politically as well. The third assumption gives us reason to think that the resultant pressures will not remain invisible but will actually be brought to bear in the political arena.

The issue of potential benefits is an important one, and a familiar example may help to illuminate it. In both great wars of this century, belligerent governments have faced an intensified demand for industrial labor and, because of the military’s need for manpower, a reduced supply. That situation has positioned workers—and, in the U.S. case, such traditionally disadvantaged workers as blacks and women—to demand greatly increased compensation: these groups, in short, have had large potential gains. Naturally, governments and employers have endeavored to deny them those gains; but in many cases—Germany in World War I, the United States in World War II, Britain in both world wars—the lure of sharing in the potential gains has induced trade on leaders, and workers themselves, to organize and demand more. Similarly, when transportation costs fall, governments may at first partially offset the effect by imposing protection. Owners of abundant factors nonetheless still have substantial potential gains from trade, which they may mortgage, or on which others may speculate, to pressure policy toward lower levels of protection.

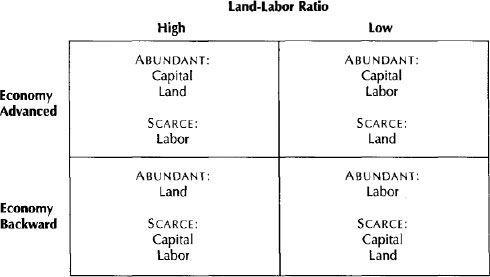

So much for politics. As regards the economic aspect, I propose to adopt with minor refinements the traditional three-factor model—land, labor, and capital—and to assume…that the land-labor ratio informs us fully about any country’s endowment of those two factors…. No country, in other words, can be rich in both land and labor: a high land-labor ratio implies abundance of land and scarcity of labor; a low ratio signifies the opposite. Finally, I shall simply define an advanced economy as one in which capital is abundant.

This model of factor endowments… permits us in theory to place any country’s economy into one of four cells (see Figure 1), according to whether it is advanced or backward and whether its land-labor ratio is high or low. We recognize, in other words, only economies that are: (1) capital rich, land rich, and labor poor; (2) capital rich, land poor, and labor rich; (3) capital poor, land rich, and labor poor; or (4) capital poor, land poor, and labor rich.

FIGURE 1. |

Four Main Types of Factor Endowments |

POLITICAL EFFECTS OF EXPANDING TRADE

The Stolper-Samuelson theorem, applied to our simple model, implies that increasing exposure to trade must result in urban-rural conflict in two kinds of economies, and in class conflict in the two others. Consider first the upper right-hand cell of Figure 1: the advanced (therefore capital-rich) economy endowed abundant in labor but poorly in land. Expanding trade must benefit both capitalists and workers; it harms only landowners and the pastoral and agricultural enterprises that use land intensively. Both capitalists and workers—which is to say, almost the entire urban sector—should favor free trade; agriculture should on the whole be protectionist. Moreover, we expect the capitalists and the workers to try, very likely in concert, to expand their political influence. Depending on preexisting circumstances, they may seek concretely an extension of the franchise, a reapportionment of seats, a diminution in the powers of an upper house or of a gentry-based political elite, or a violent “bourgeois” revolution.

Urban-rural conflict should also rise in backward, land-rich economies (the lower left-hand cell of Figure 1) when trade expands, albeit with a complete reversal of fronts. In such “frontier” societies, both capital and labor are scarce; hence both are harmed by expanding trade and, normally, will seek protection. Only land is abundant, and therefore only agriculture will gain from free trade. Farmers and pastoralists will try to expand their influence in some movement of a “populist” and antiurban stripe.

Conversely, in backward economies with low land-labor ratios (the lower right-hand cell of Figure 1), land and capital are scarce and labor is abundant. The model therefore predicts class conflict: labor will pursue free trade and expanded political power (including, in some circumstances, a workers’ revolution); landowners, capitalists, and capital-intensive industrialists will unite to support protection, imperialism, and a politics of continued exclusion.

The reverse form of class conflict is expected to arise in the final case, that of the advanced but land-rich economy (the upper left-hand cell of Figure 1) under increasing exposure to trade. Because both capital and land are abundant, capitalists, capital-intensive industries, and agriculture will all benefit from, and will endorse, free trade; labor being scarce, workers and labor-intensive industries will resist, normally embracing protection and (if need be) imperialism. The benefited sectors will seek to expand their political power, if not by disfranchisement then by curtailment of workers’ economic prerogatives and suppression of their organizations.

These implications of the theory of international trade (summarized in Figure 2) seem clear, but do they in any way describe reality?… [I]t is worth observing how closely the experience of three major countries—Germany, Britain, and the United States—conforms to this analysis in the period of rapidly expanding trade in the last third of the nineteenth century; and how far it can go to explain otherwise puzzling disparities in those states’ patterns of political evolution.

Germany and the United States were both relatively backward (i.e., capital-poor) societies: both imported considerable amounts of capital in this period, and neither had until late in the century anything like the per capita industrial capacity of the United Kingdom or Belgium. Germany, however, was rich in labor and poor in land; the United States, of course, was in exactly the opposite position. (Again, we observe that the United States imported, and Germany exported—not least to the United States—workers, which is not surprising since, at midcentury, Prussia’s labor-land ratio was fifteen times that of the United States.)

FIGURE 2. |

Predicted Effects of Expanding Exposure to Trade |

The theory predicts class conflict in Germany, with labor the “revolutionary” and free-trading element, and with land and capital united in support of protection and imperialism. Surely this description will not ring false to any student of German socialism or of Germany’s infamous “marriage of iron and rye!” For the United States, conversely, the theory predicts—quite accurately, I submit—urban-rural conflict, with the agrarians now assuming the “revolutionary” and free-trading role; capital and labor unite in a protectionist and imperialist coalition….

Britain, on the other hand, was already an advanced economy in the nineteenth century. Its per capita industrial output far exceeded that of any other nation, and it exported capital in vast quantities. That it was also rich in labor is suggested by its extensive exports of that factor to the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Africa; in fact, Britain’s labor-land ratio then exceeded Japan’s by 50 percent and was over thirty times that of the United States. Britain therefore falls into the upper right-hand quadrant of Figure 1 and is predicted to exhibit a rural-urban cleavage whose fronts are opposite those found in the United States: capitalists and labor unite in support of free trade and in demands for expanded political power, while landowners and agriculture support protection and imperialism.

Although this picture surely obscures important nuances, it illuminates crucial differences—between, for example, British and German political development in this period. In Britain, capitalists and labor united in the Liberal party and forced an expanded suffrage and curtailment of (still principally land-owning) aristocratic power. In Germany, liberalism shattered, the suffrage at the crucial level of the individual states was actually contracted, and—far from eroding aristocratic power—the bourgeoisie grew more and more verjunkert in style and aspirations.

POLITICAL EFFECTS OF DECLINING TRADE

When rising costs or declining security substantially increases the risks or costs of external trade, the gainers and losers in each situation are simply the reverse of those under increasing exposure to trade. Let us first consider the situation of the highly developed (and therefore by definition capital-rich) economies.

In an advanced economy with a high land-labor ratio (the upper left-hand cell of Figure 1), we should expect intense class conflict precipitated by a newly aggressive working class. Land and capital are both abundant in such an economy; hence, under declining trade owners of both factors (and producers who use either factor intensively) lose. Moreover, they can resort to no such simple remedy as protection or imperialism. Labor being the only scarce resource, workers and labor-intensive industries are well positioned to reap a significant windfall from the “protection” that dearer or riskier trade affords; and, according to our earlier assumption, like any other benefited class they will soon endeavor to parlay their greater economic power into greater political power. Capitalists and landowners, even if they were previously at odds, will unite to oppose labor’s demands.

Quite to the contrary, declining trade in an advanced economy that is labor rich and land poor (the upper right-hand cell of Figure 1) will entail renewed urban-rural conflict. Capital and labor are both abundant, and both are harmed by the contraction of external trade. Agriculture, as the intense exploiter of the only scarce factor, gains significantly and quickly tries to translate its gain into greater political control.

Urban-rural conflict is also predicted for backward, land-rich countries under declining trade; but here agriculture is on the defensive. Labor and capital being both scarce, both benefit from the contraction of trade; land, as the only locally abundant factor, is threatened. The urban sectors unite, in a parallel to the “radical” coalition of labor-rich developed countries under expanding trade discussed previously, to demand an increased voice in the state.

Finally, in backward economies rich in labor rather than land, class conflict resumes, with labor this time on the defensive. Capital and land, as the locally scarce factors, gain from declining trade; labor, locally abundant, suffers economic reverses and is soon threatened politically.

Observe again, as a first test of the plausibility of these results—summarized in Figure 3—how they appear to account for some prominent disparities of political response to the last precipitous decline of international trade, the depression of the 1930s. The U.S. New Deal represented a sharp turn to the left and occasioned a significant increase in organized labor’s political power. In Germany, a depression of similar depth (gauged by unemployment rates and declines in industrial production) brought to power first Hindenburg’s and then Hitler’s dictatorship. Landowners exercised markedly greater influence than they had under Weimar; and indeed a credible case can be made that the rural sector was the principal early beneficiary of the early Nazi regime. Yet this is exactly the broad difference that the model would lead us to anticipate, if we accept that by 1930 both countries were economically advanced—although Germany, after physical reparations and cessions of industrial regions, was surely less rich in capital than the United States—but the United States held land abundantly, which in Germany was scarce (respectively, the left- and right-hand cells of the upper half of Figure 3). Only an obtuse observer would claim that such factors as cultural inheritance and recent defeat in war played no role; but surely it is also important to recognize the sectoral impact of declining trade in the two societies.

FIGURE 3. |

Predicted Effects of Declining Exposure to Trade |

As regards the less developed economies of the time, it may be profitable to contrast the depression’s impact on such South American cases as Argentina and Brazil with its effects in the leading Asian country, Japan. In Argentina and Brazil, it is usually asserted, the depression gave rise to, or at the least strengthened, “populist” coalitions that united labor and the urban middle classes in opposition to traditional, landowning elites. In Japan, growing military influence suppressed representative institutions and nascent workers’ organizations, ruling in the immediate interest—if hardly under the domination—of landowners and capitalists. Similar suppressions of labor occurred in China and Vietnam. In considering these contrasting responses, should we not take into account that Argentina and Brazil were rich in land and poor in labor, while in Japan (and, with local exceptions, in Asia generally) labor was abundant and land was scarce?…

POSSIBLE OBJECTIONS

Several objections can plausibly be raised to the whole line of analysis that I have advanced here….

[1.] It may be argued that the effects sketched out here will not obtain in countries that depend only slightly on trade. A Belgium, where external trade (taken as the sum of exports and imports) roughly equals gross domestic product (GDP), can indeed be affected profoundly by changes in the risks or costs of international commerce; but a state like the United States in the 1960s, where trade amounted to scarcely a tenth of GDP, will have remained largely immune.

This view, while superficially plausible, is incorrect. The Stolper-Samuelson result obtains at any margin; and in fact, holders of scarce factors have been quite as devastated by expanding trade in almost autarkic economics—one need think only of the weavers of India or of Silesia, exposed in the nineteenth century to the competition of Lancashire mills—as in ones previously more dependent on trade.

[2.] Given that comparative advantage always assures gains from trade, it may be objected that the cleavages described here need not arise at all: the gainers from trade can always compensate the losers and have something left over; trade remains the Pareto-superior outcome. As Stolper and Samuelson readily conceded in their original essay, this is perfectly true. To the student of politics, however, and with even greater urgency to those who are losing from trade in concrete historical situations, it remains unobvious that such compensation will in fact occur. Rather, the natural tendency is for gainers to husband their winnings and to stop their ears to the cries of the afflicted. Perhaps only unusually strong and trustworthy states, or political cultures that especially value compassion and honesty, can credibly assure the requisite compensation… and even in those cases, substantial conflict over the nature and level of compensation will usually precede the ultimate agreement.

[3.] Equally, one can ask why the cleavages indicated here should persist. In a world of perfectly mobile factors and rational behavior, people would quickly disinvest from losing factors and enterprises (e.g., farming in Britain after 1880) and move to sectors whose auspices were more favorable. Markets should swiftly clear; and a new, if different, political equilibrium should be achieved.

To this two answers may be given. First, in some cases trade expands or contracts so rapidly and surprisingly as to frustrate rational expectations. Especially in countries that experience a steady series of such exogenous shocks—the case in Europe, I would contend, from 1840 to the present day—divisions based on factor endowments (which ordinarily change only gradually) will be repeatedly revived. Second, not infrequently some factors’ privileged access to political influence makes the extraction of rents and subsidies seem cheaper than adaptation: Prussian Junkers, familiarly, sought (and easily won) protection rather than adjustment. In such circumstances, adaptation may be long delayed, sometimes with ultimately disastrous consequences.

At the same time, it should be conceded that, as improved technology makes factors more mobile… and anticipation easier, the theory advanced here will likely apply less well. Indeed, this entire analysis may be a historically conditioned one, whose usefulness will be found to have entered a rapid decline sometime after 1960….

[4.] This analysis, some may contend, reifies such categories as “capital,” “labor,” and “land,” assuming a unanimity of preference that most countries’ evidence belies. In fact, a kind of shorthand and a testable hypothesis are involved: a term like “capital” is the convenient abbreviation of “those who draw their income principally from investments, plus the most capital-intensive producers”; and I indeed hypothesize that individuals’ political positions will vary with their derivation of income—or, more precisely, of present value of all anticipated future income—from particular factors.

A worker, for example, who derives 90 percent of her income from wages and 10 percent from investments will conform more to the theory’s expectation of “labor” ‘s political behavior than one who depends half on investments and half on wages. An extremely labor-intensive manufacturer will behave less like a “capitalist” than a more capital-intensive one. And a peasant (as noted previously) who depends chiefly on inputs of his own labor will resemble a “worker,” whereas a more land-intensive neighbor will behave as a “landowner.”

[5.] Finally, it may be objected that I have said nothing about the outcome of these conflicts. I have not done so for the simple reason that I cannot: history makes it all too plain, as in the cases of nineteenth-century Germany and America, that the economic losers from trade may win politically over more than the short run. What I have advanced here is a speculation about cleavages, not about outcomes. I have asserted only that those who gain from fluctuations in trade will be strengthened and emboldened politically; nothing guarantees that they will win. Victory or defeat depends, so far as I can see, both on the relative size of the various groups and on those institutional and cultural factors that this perspective so resolutely ignores.

CONCLUSION

It is essential to recall what I am not claiming to do…. I do not contend that changes in countries’ exposure to trade explain all, or even most, of their varying patterns of political cleavage. It would be foolish to ignore the importance of ancient cultural and religious loyalties, of wars and migrations, or of such historical memories as the French Revolution and the Kulturkampf. Other cleavages antedate, and persist through, the ones I discuss here, shaping, crosscutting, complicating, and indeed sometimes dominating their political resolution….

In the main, I am presenting here a theoretical puzzle, a kind of social-scientific “thought experiment” in Hempel’s original sense: a teasing out of unexpected, and sometimes counterintuitive, implications of theories already widely accepted. For the Stolper-Samuelson theorem is generally, indeed almost universally, embraced; yet, coupled with a stark and unexceptionable model of the political realm, it plainly implies that changes in exposure to trade must profoundly affect nations’ internal political cleavages. Do they do so? If they do not, what conclusions shall we draw, either about our theories of international trade, or about our understanding of politics?