The decisive battles of the First World War were fought in the trenches of northeastern France and in parts of Belgium. Millions of soldiers on both sides, Allied and German, died of gunfire and gas attacks before Germany surrendered on November 11, 1918. (The Toronto Reference Library)

Chapter Six

THE WAR TO END ALL WARS

In the early years of the twentieth century Europe's five most powerful nations were Britain, France, Germany, Russia, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. While all were rich in resources and industry, each nation had doubts and complaints about the others. Germany was jealous of Britain's mighty navy. France wished it had an army as large and disciplined as Germany's. Russia spent its wealth in building a military with bigger guns and stronger fortifications, all in the interests of not looking second-rate in comparison with the others. Germany objected that it had far fewer colonies in Asia and Africa than either Britain or France had. The British and French were growing more prosperous from their colonization of both continents, and the Germans considered their monopoly to be unfair.

Austria-Hungary, the least of the five powers, felt it received no respect from any of the others except Germany The population of the Austro-Hungarian Empire included groups of citizens divided by a dozen languages and five religions. The German Austrians, led by the prolific Habsburg family, dominated the empire for centuries, even though they were outnumbered by the Serbians and the other Slavic peoples who made up a large and unhappy subgroup within the empire.

Europe was officially at peace, but it was a nervous peace. None of the countries said they wanted war. All tried to manage workable diplomatic relations with the rest, and France and Russia maintained an alliance that had lasted for decades. Still, the five powers kept themselves armed just in case someone started a war. By “someone,” France, Russia, and Britain had Germany in mind, the country that was involved in more differences of opinion than anybody else. To the others, Germany seemed to bargain with a chip on its shoulder, and by 1914, German leaders were signaling that they might challenge the rest of the powers at any moment.

In June 1914, Austria-Hungary held its army's annual practice battle in the empire's province of Bosnia. Archduke Franz Ferdinand of the Habsburg family arrived in Bosnia on June 25 as the senior official in charge of supervising the battle. The archduke had the best of credentials; he was inspector general of the army and nephew of Austria-Hungary's Emperor Franz Josef.

When the army finished its practice battle three days later, the archduke and his wife were driven many miles in a procession of cars for a ceremonial visit to Bosnia's governor. The governor's residence was in the city of Sarajevo. Lying in wait for the archduke in the city's streets were five young Austrian citizens of Serbian background who had armed themselves with bombs and pistols. The five belonged to an extremist group of Nationalist Serbs who resented the rule of the Habsburgs. They intended to assassinate the archduke.

In June 1914, when Serbian nationalists assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (above right), the stage was set for the outbreak of the First World War The man in the lavish sideburns striding in front of the archduke is Franz Joseph, the Austro-Hungarian emperor (The Toronto Reference Library)

As the royal motorcade entered Sarajevo, an assassin threw a bomb at the archdukes car. The bomb bounced off its target and exploded under the next car in the line, wounding an officer. The motorcade proceeded on its way, giving no sign of panic. Forty-five minutes later, still on the way to the governors house, the chauffeur driving the archduke made a wrong turn. He realized his mistake right away, but while he was backing up and turning around, he came to a stop in front of a man who was standing on the sidewalk. By a horrible coincidence, the man was another of the five Serbian assassins. He pulled out his pistol and shot the archduke and his wife. They died on the spot. The Serb killer was arrested.

The archduke's shocking assassination set off a chain of reactions among Europe's five powers. Austria-Hungary's Habsburgs were eager to declare war on the tiny kingdom of Serbia, which supported the Serb radicals within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. But the Habsburgs wanted assurance that Germany would help them in their fight. The Germans encouraged the Habsburgs to go ahead with an invasion of Serbia, whenever they were ready. Russia, long devoted to the Serbs, announced its support of Serbia in any war that was brought against the little kingdom. France already had a treaty with Russia that required each country to come to the aid of the other if Germany invaded one of the two. And both France and England were joined under an ancient treaty, in which they promised to protect Belgium if the Germans violated the country's neutrality.

By late July, after a month of bickering among all the nations, both Russia and Germany threatened to mobilize their armies at any minute. Diplomats from England and France warned the Germans and the Russians of the trigger effect of mobilization – if one country took up arms, then all the others would soon do the same. Neither Russia nor Germany appeared to appreciate the danger.

The Germans were feeling bold. In their opinion, they had a tremendous military scheme in place. It was called the Schlieffen Plan, named after the man who designed it, Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen, once chief of the German Great General Staff. The minutely detailed plan committed seven-eighths of the German army to a massive assault on France. As far as Germany was concerned, the Schlieffen Plan guaranteed that the Germans would capture Paris and defeat France in exactly forty-two days. After that, the German army would turn to Russia and give it the same beating.

But Germany didn't pull the first trigger. That role was filled by the Austro-Hungarian Empire. On Tuesday July 28, still fuming over the murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia. Two days later, Serbia's protector, Russia, announced that it was mobilizing its army. On the following afternoon, July 31, Germany dispatched telegrams to both Russia and Russia's good friend France, advising that Germany would mobilize its own army unless the Russians promised to suspend their war measures. The Germans demanded an answer from the Russians within twelve hours.

Millicent White, the senior nurse at Edith Cavell's clinic, took the events in Germany and Russia as a signal of big trouble ahead. Early on Saturday morning, August 1, she sent a telegram to Edith in Norwich, warning her that war seemed to be on the way. That afternoon, while Edith was weeding her mother's garden, a messenger delivered the telegram. When Edith read it, Mrs. Cavell begged her not to return to Brussels.

“My duty is with my nurses,” Edith said.

On Saturday evening, Russia told Germany that it was rejecting the German demand to stop the mobilization of the Russian army. Germany's response was to announce that it, too, was mobilizing its army and to declare war on Russia.

The next day, Sunday, Germany delivered an ultimatum to Belgium – unless the Belgians allowed the German army to march through the country without interference, Germany would treat it as an enemy. The Schlieffen Plan depended on a quick German passage to France by way of Belgium, and Germany told the Belgians that they had twenty-four hours to make up their minds. As everybody recognized, the German demands indicated that Germany was about to launch its war against France.

Edith Cavell took the Sunday-evening boat across the English Channel to Ostend, on the Belgian coast, where she caught a train that would reach Brussels early Monday morning.

In Brussels, King Albert I of Belgium summoned his military leaders to the Senate chamber late on Sunday night. For hours, past midnight and into Monday morning, the men discussed Belgium's answer to the German ultimatum. Albert, an honorable man, didn't want Belgium to be the cause of a full-scale European war. On the other hand, Germany's bullying made him furious. The answer that Albert and his generals drew up said, in the most dignified language, that Belgium would oppose any attack on its borders. A document with the answer was delivered to the German legation in Brussels at seven o'clock on Monday morning. That was just about the time when Edith arrived back in the city to take charge of her clinic.

As six of the clinic's nurses in training were Germans, Edith's first order of business was to get them out of Belgium. None of the European countries had yet fired a shot, but Edith knew that Brussels could soon become a dangerous spot for the six young German women. She wasn't worried about her German maid, Marie, who was older and could handle herself in Brussels. The risk was different for the youthful and inexperienced nurses. Edith took the six to the train station and saw them off to their fatherland.

When she returned to the clinic, Edith began preparations to care for soldiers wounded in battle. If Germany invaded Belgium, Edith expected that the Belgian army would need all the hospital beds in the city to look after casualties from the war front. She was also certain that the clinic would come under the rules and regulations of the International Committee of the Red Cross when war broke out. This meant that Edith and her nurses would be called on to treat the wounded from every country, both allies and enemies, both Belgian and German. The clinic had to be ready to play its part.

Later on Monday, Germany pushed Europe to the brink of all-out war. Confident that the Schlieffen Plan would bring an early victory, the Germans declared war on France. A few hours after the declaration, when Germany's ultimatum to Belgium expired, German troops massed along the border between the two countries. In the darkness of early Tuesday morning, the Germans crossed into Belgium.

With Germany's invasion of Belgium, the old treaty signed by France and England guaranteeing Belgian neutrality came into effect. By midnight, Tuesday, August 4, Britain was at war with Germany. So were France and Russia. The countries of the British Empire, Canada among them, declared war on Germany, and within a week, Austria-Hungary joined Germany in the war against England and all of the other Allied nations.

The war had begun. Everybody called it the Great War because it involved all of Europe's powers. It was expected to settle rivalries that had existed over the past century. For this reason, it was also called the War to End All Wars. It would become known, finally and officially, under a third name, the First World War, in 1943, four years after the start of the Second World War.

Under all its names, the war lasted from the summer of 1914 until late in 1918, and it didn't come near to ending all wars. But it was the most deadly war in history until then. Millions from both sides died in the fighting. The overwhelming majority of deaths resulted from soldiers shelling and shooting at one another in massive artillery and infantry battles. But among the others who gave their lives were men and women who never picked up a gun. Edith Cavell was one of them.

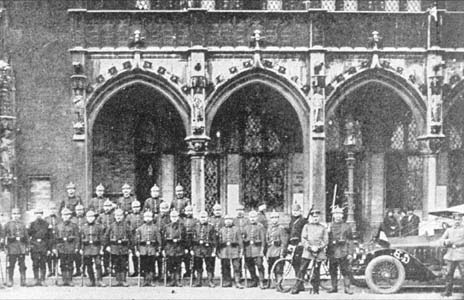

OPPOSITE: The men in the spiked helmets are German soldiers posing in front of the beautiful town hall in Brussels, which the Germans occupied in August 1914. (The Royal London Hospital Archives)