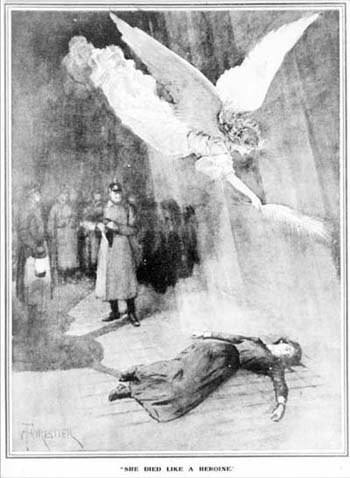

Britain issued thousands of posters and postcards after Edith's execution. The pictures, intended as propaganda to stir citizens against the Germans, weren't always accurate. This idealized poster shows Edith in her uniform, which she didn't wear on the day she died, nor does the poster reveal Edith's fatal bullet wounds to her forehead and chest. (The Royal London Hospital Archives)

Chapter Twelve

EDITH'S LEGACY

On October 21, a few days after word of Edith's execution blazed across the front pages of Britain's newspapers, the bishop of London preached about her in a special ceremony at the church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields. He said that Britain didn't need a campaign to recruit more soldiers; Edith's execution was incentive all by itself for young men to join the armed forces. The bishop was right. In the two months preceding Edith's death, the enlistment rate into the British Expeditionary Force averaged just under five thousand men per week. In the two months following news of her execution reaching Britain, the weekly average jumped to over ten thousand.

The same thing happened in France and in the countries of the British Empire. Fired up by Edith's courageous example, and furious at the barbarian Germans, young men rushed to enlistment offices. Edith had inspired them to go to war. Britain's politicians seized on Edith as a propaganda tool, playing up the need to follow her path. “She has taught the bravest men among us the supreme lesson of courage,” Britain's Prime Minister Herbert Asquith said in the House of Commons. But his words were hardly needed. The story of Edith Cavell had already taken hold on the public's imagination, and fighting men marched to war in her memory.

In Brussels, in the days after Edith's execution, three other members of the secret network – Louise Thuliez, Countess Jeanne de Belleville, and Louis Séverin – waited at St. Gilles Prison to take their turn before the firing squad. But for them, death never came. The Germans were stunned at the worldwide revulsion stirred by Edith's execution. Germany's leader, Kaiser Wilhelm II, announced that, from then on, no woman would be shot unless he consented. He gave the impression that consent would never come from him. The kaiser's announcement was too late to repair the damage that Germany had done to its reputation. But the lives of the three prisoners in St. Gilles were saved. The Germans converted the death sentences of Thuliez, de Belleville, and Séverin to terms in prison.

These three and their colleagues in the secret organization didn't go free until the end of the war. All survived their imprisonment, though Ada Bodart never recovered from the experience and died not long after, ill and penniless (the fate of Bodart's teenage son, Philippe, was never known). Princess de Croy returned to her château at Bellignies, and Louise Thuliez went back to teaching school. Everybody reclaimed their old lives. Albert Libiez, the Mons lawyer, took up his practice, and years later, in the Second World War, he once again worked secretly against Germany.

This time, when he was caught, the German Nazis sent him to a concentration camp where Libiez died, leaving behind a record as a fighter of injustice in two world wars.

In November 1915, Nurse Elisabeth Wilkins decided Brussels was too dangerous for her. The Germans had been rounding up evidence against Wilkins, and she thought her days of freedom might soon be over. When she fled back to Britain, she took Grace Jemmett with her. Jemmett went to live with her parents, while Wilkins continued her career in nursing, ending it as Matron at a hospital in Somerset County.

Jackie, the dog, left Brussels too. After his mistress' execution, he was sent to Bellignies, where he lived until his death in 1923. Princess de Croy his last mistress, arranged for him to be embalmed. Then she shipped Jackie's stuffed body to Norwich, where, odd as it seems, it was put on display for decades as the faithful pet of Britain's heroine.

The war lasted until November 11, 1918. From mid-1915 to late 1918, the fighting raged on several fronts: in Russia to the east; in Turkey, where the Turks fought as Germany's ally; and at sea, where the Germans battled Britain's traditionally powerful navy. But the most decisive warfare took place on the western front in northeastern France and in parts of Belgium. It was in the trenches of the west that the armies fought the war to its conclusion.

The battle wasn't continuous, but more a long and terrible standoff interrupted by individual clashes. These were bloody and futile. Both sides, Germany and the Allied nations, faced one another along a front of 465 miles, from the border of one neutral country, Switzerland, to the border of another neutral country, Holland. Ten thousand Allied soldiers were packed into each mile of the front lines, with thousands more ready to move up. When they went into periodic battle, the results were grim.

On a single summer day in 1916, in one episode at the Battle of the Somme in France, fifty thousand British troops died as they advanced straight into German fire. The deaths produced no strategic result, not moving the Allied front at the Somme from the spot it had been in at the beginning of the day. In the last three years of the war, 3 million men from the Allied armies died along the length of the western trenches. Throughout the slaughter, the front stayed essentially in place, the Allies pushing ahead not much more than five miles in the entire three years.

The Americans joined the war on the Allies' side in 1917, drawn into the conflict by two German blunders. The first came when Germany killed 128 American citizens in the sinking of the passenger liner Lusitania in 1915. The other involved German agents that set out to provoke a diversionary war in America's neighbor Mexico. Those events, plus America's lingering horror at Edith Cavell's execution, stirred the United States to combat. The country's entry into the war and the British invention of the tank combined to give the Allies an edge over the Germans.

But fatigue decided the war in the end. Over the years of fighting, both sides wore down. Millions of men died, and millions more suffered wounds. The soldiers grew sick of the massacre, which came to seem pointless. Everyone was tired, but the Germans tired first. As several historians later wrote, it could just as easily have been one of the Allies, perhaps France or Russia, who decided to quit the fighting before anyone else. But Germany was the country that surrendered on November 11, 1918, and the killing finally stopped.

On March 17, 1919, in a ceremony in Brussels, an official British party, which included the king and queen of England, removed Edith's body from the grave on the shooting range. The exhumation was the first step in her reburial at home in Norfolk. The trip from Brussels to Norwich proceeded in stages, lasting three days altogether, with several stops for ceremonies recognizing Edith's courage and sacrifice. Accompanying the coffin were Edith's two sisters, Florence and Lillian. Edith's mother had died less than a year earlier, distraught and bewildered by her oldest daughter's execution.

At a ceremony in March 1919, Edith's body was removed from its original grave in Brussels for reburial on the grounds of Norwich Cathedral in England. Attending the ceremony were King George V and Queen Mary of England and, in the rear wearing all the medals, King Albert I of Belgium. (The Royal London Hospital Archives)

When the cortège traveled by train from Dover to London, church bells rang in every village and people lined the tracks, their heads bowed. In London, the first half of the burial service took place at Westminster Abbey, then the mourners got back on the train to Norwich for the rest of the service. Edith's brother, Jack, joined the crowd at Norwich's famous cathedral. So did the man who could have become Edith's husband, Eddy Cavell. At the service, Bishop Bertram Pollock of Norwich remembered Edith in her youth. He said she was “an innocent, unselfish, devout and pretty girl.”

Edith was reburied in a plot at the rear of the cathedral. Her final resting place was small and inconspicuous, marked by a plain white stone cross. Even the simple grave might have been too showy for the modest Edith.

Edith would have felt just as embarrassed by the number of ways that England and other countries continued to pay tribute to her. Renowned English actresses played Edith in the story of her life on the screen and on the stage: Sybil Thorndike in a 1928 movie, Anna Neagle in a 1939 film, and Joan Plowright in a 1982 play. Around the world, everything from streets to mountains were named after Edith. In the town of Beaulieu-sur-Mer, on France's Mediterranean, a pretty road was renamed Rue Edith Cavell in gratitude for all the French soldiers rescued by Edith. And Canada put her name on a peak in the Rocky Mountains near Jasper, Alberta. The peak, 3,363 meters high, became Mount Edith Cavell.

OPPOSITE, CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT:

This stone memorial stands outside the Institut Edith Cavell in Brussels. It celebrates both Edith and Marie Depage, wife of Dr. Antoine Depage who founded the clinic that later became the Institut. (The Royal London Hospital Archives)

The memorial to Edith in front of Norwich Cathedral describes her as “nurse, patriot and martyr.” She took great pride in her career as a nurse, but she never thought of herself as a martyr. (Jack Batten)

Communities all over the world honored Edith by putting her name on streets and avenues. This sign borders a road running through the pretty little town of Beaulieu-sur-Mer on the French Riviera. (Marjorie Harris)

This sign in the East End of Toronto faces a street originally named Dresden Avenue. Toronto's city council changed the name in the spring of 1916 as a gesture to honor Edith. (Jack Batten)

In England, Belgium, and countless other countries, governments and citizens made sure that Edith's name would never fade from memory. A new nurses'residence, built at the London Hospital in 1916, was intended to be named Alexandra Home, after the widow of King Edward VII, but with Queen Alexandra's approval, the name was changed to Edith Cavell Home. In Brussels, the clinic where Edith served as the first Matron came to be called the Cavell Institute. A bust of her stands outside Norwich Cathedral, and a large bas-relief showing Edith and two soldiers, put up by the Societa Italo-Canadese on November 11, 1922, occupies a plaza in front of the Toronto General Hospital.

The best-known Cavell memorial is the statue of Edith that faces south across Trafalgar Square in London. The statue shows Edith looking far more imposing than she ever was in life. Below the statue, the pedestal carries Edith's name, together with the place, date, and time of her execution. That was all the information on the pedestal when the memorial was unveiled in the early 1920s. But in 1924, a man named F.W. Jowitt, the commissioner of public works in the government of the day, decided that the pedestal needed more. He ordered that Edith's declaration to the Reverend Stirling Gahan on the last night of her life be carved into the stone under the date of her death:

PATRIOTISM IS NOT ENOUGH. I MUST HAVE NO HATRED OR BITTERNESS FOR ANYONE.

The words were Edith's message to the world. She helped hundreds of her fellow countrymen escape the German enemy, an action that showed how much her country meant to her. But simple patriotism didn't go far enough. It couldn't prevent wars; it might even encourage them. In Edith's opinion, the only course of action was to reach out and accept all men and women, no matter what countries they came from. In saying her two famous lines, Edith was only doing her duty as she saw it.