The price of almost everything in your daily life is determined by the law of supply and demand. What you pay for your lettuce, tomatoes, eggs, and beef depends on how much of each is available and how many people want these items. Even in former Communist countries, where the difference between haves and have-nots was theoretically nonexistent, supply and demand held sway. There, state-owned goods were always in short supply and were often available only to the privileged class or on the black market to those who could pay the exorbitant prices.

This basic principle of supply and demand also applies to the stock market, where it is more important than the opinions of all the analysts on Wall Street, no matter what schools they attended, what degrees they earned, or how high their IQs.

It’s hard to budge the price of a stock that has 5 billion shares outstanding because the supply is so large. Producing a rousing rally in these shares would require a huge volume of buying, or demand. On the other hand, it takes only a reasonable amount of buying to push up the price of a stock with 50 million shares outstanding, a relatively smaller supply.

So if you’re choosing between two stocks to buy, one with 5 billion shares outstanding and the other with 50 million, the smaller one will usually be the better performer, if other factors are equal. However, since smaller-capitalization stocks are less liquid, they can come down as fast as they go up, sometimes even faster. In other words, with greater opportunity comes significant additional risk. But there are definite ways of minimizing your risk, which will be discussed in Chapters 10 and 11.

The total number of shares outstanding in a company’s capital structure represents the potential amount of stock available. But market professionals also look at the “floating supply”—the number of shares that are available for possible purchase after subtracting stock that is closely held. Companies in which top management owns a large percentage of the stock (at least 1% to 3% in a large company, and more in small companies) generally are better prospects because the managers have a vested interest in the stock.

There’s another fundamental reason, besides supply and demand, why companies with a large number of shares outstanding frequently produce slower results: the companies themselves may be much older and growing at a slower rate. They are simply too big and sluggish.

In the 1990s, however, bigger-capitalization stocks outperformed small-cap issues for several years. This was in part related to the size problem experienced by the mutual fund community. It suddenly found itself awash in new cash as more and more people bought funds. As a result, larger funds were forced to buy more bigger-cap stocks. This need to put their new money to work made it appear that they favored bigger-cap issues. But this was contrary to the normal supply/demand effect, which favors smaller-cap stocks with fewer shares available to meet increases in institutional investor demand.

Big-cap stocks do have some advantages: greater liquidity, generally less downside volatility, better quality, and in some cases less risk. And the immense buying power that large funds have these days can make top-notch big stocks advance nearly as fast as shares of smaller companies.

Big companies may seem to have a great deal of power and influence, but size often begets a lack of imagination and productive efficiency. Large companies are often run by older and more conservative “caretaker managements” that are less willing to innovate, take risks, and move quickly and wisely to keep up with rapidly changing times. In most cases, top managers of large companies don’t own a lot of their company’s stock. This is a serious deficiency that should be corrected. To the savvy investor, it suggests that the company’s management and employees don’t have a personal interest in seeing the company succeed. In some cases, large companies also have multiple layers of management that separate senior executives from what’s going on at the customer level. And for companies competing in a capitalist economy, the ultimate boss is the customer.

Communication of information continues to change at an ever-faster rate. A company that has a hot new product today will find its sales slipping within two or three years if it doesn’t continue to bring relevant, superior new products to market. Most new products, services, and inventions come from young, hungry, and innovative small- and medium-sized companies with entrepreneurial management. Not coincidentally, these smaller public and nonpublic companies grow faster and create somewhere between 80% and 90% of the new jobs in the United States. Many of them are in the service or technology and information industries. This is possibly where the great future growth of America lies. Microsoft, Cisco Systems, and Oracle are just a few examples of dynamic small-cap innovators of the 1980s and 1990s that continually grew and eventually became big-cap stocks.

If a mammoth older company creates an important new product, it may not help the stock materially because the product will probably account for only a small percentage of the company’s total sales and earnings. The product is simply a small drop in a bucket that’s now just too big.

From time to time, companies make the mistake of splitting their stocks excessively. This is sometimes done on advice from Wall Street investment bankers. In my opinion, it’s usually better for a company to split its shares 2-for-1 or 3-for-2 than to split them 3-for-1 or 5-for-1. (When a stock splits 2-for-1, you get two shares for each share you previously held, but the new shares sell for half the price.) Oversized splits create a substantially larger supply and may put a company in the more lethargic, big-cap status sooner.

Incidentally, a stock will usually end up moving higher after its first split in a new bull market. But before it moves up, it will go through a correction for a period of weeks.

It may be unwise for a company whose stock has gone up in price for a year or two to declare an extravagant split near the end of a bull market or in the early stage of a bear market. Yet this is exactly what many corporations do.

Generally speaking, these companies feel that lowering the share price of their stock will attract more buyers. This may be the case with some smaller buyers, but it also may produce the opposite result—more sellers—especially if it’s the second split within a year or two. Knowledgeable pros and a few shrewd individual traders will probably use the excitement generated by the oversized split as an opportunity to sell and take their profits. In addition, large holders who are thinking of selling might figure it will be easier to unload their 100,000 shares before a 3-for-1 split than to sell 300,000 shares afterward. And smart short sellers pick on stocks that are heavily owned by institutions and are starting to falter after huge price run-ups.

A stock will often reach a price top around the second or third time it splits. Our study of the biggest winners found that only 18% of them had splits in the year preceding their great price advances. Qualcomm topped in December 1999, just after its 4-for-1 stock split.

In most but not all cases, it’s usually a good sign when a company, especially a small- to medium-sized growth company that meets the CAN SLIM criteria, buys its own stock in the open market consistently over a period of time. (A 10% buyback would be considered big.) This reduces the number of shares and usually implies that the company expects improved sales and earnings in the future.

As a result of the buyback, the company’s net income will be divided by a smaller number of shares, thereby increasing earnings per share. And as already noted, the percentage increase in earnings per share is one of the principal driving forces behind outstanding stocks.

From the mid-1970s to the early 1980s, Tandy, Teledyne, and Metromedia successfully repurchased their own stock, and all three achieved higher EPS growth and spectacular stock gains. Charles Tandy once told me that when the market went into a correction, and his stock was down, he would go to the bank and borrow money to buy back his stock, then repay the loans after the market recovered. Of course, this was also when his company was reporting steady growth in earnings.

Tandy’s (split-adjusted) stock increased from $2.75 to $60 in 1983, Metromedia’s soared from $30 in 1971 to $560 in 1977, and Teledyne zoomed from $8 in 1971 to $190 in 1984. Teledyne used eight separate buybacks to shrink its capitalization from 88 million shares to 15 million and increase its earnings from $0.61 a share to nearly $20.

In 1989 and 1990, International Game Technology announced that it was buying back 20% of its stock. By September 1993, IGT had advanced more than 20 times. Another big winner, home builder NVR Inc., had large buybacks in 2001. All these were growth companies. I’m not sure that company buybacks when earnings are not growing are all that sound.

After you’ve found a stock with a reasonable number of shares, check the percentage of the company’s total capitalization represented by long-term debt or bonds. Usually, the lower the debt ratio, the safer and better the company. The earnings per share of companies with high debt-to-equity ratios could be clobbered in difficult periods when interest rates are high or during more severe recessions. These highly leveraged companies are generally of lower quality and carry substantially higher risk.

The use of extreme leverage of up to 40-to-1 or 50-to-1 was common among banks, brokers, mortgage lenders, and quasi-government agencies like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac starting in 1995 and continuing until 2007. These institutions were strongly encouraged by the federal government’s actions to invest large amounts of money in subprime loans to lower-income buyers, which ultimately led to the financial and credit crisis in 2008.

Rule 1 for all competent investors and homeowners is never

ever borrow more than you can pay back. Excessive debt

hurts all people, companies, and governments.

A corporation that’s been reducing its debt as a percentage of equity over the last two or three years is worth considering. If nothing else, interest costs will be sharply reduced, helping to generate higher earnings per share.

Another thing to watch for is the presence of convertible bonds in the capital structure; earnings could be diluted if and when the bonds are converted into shares of common stock.

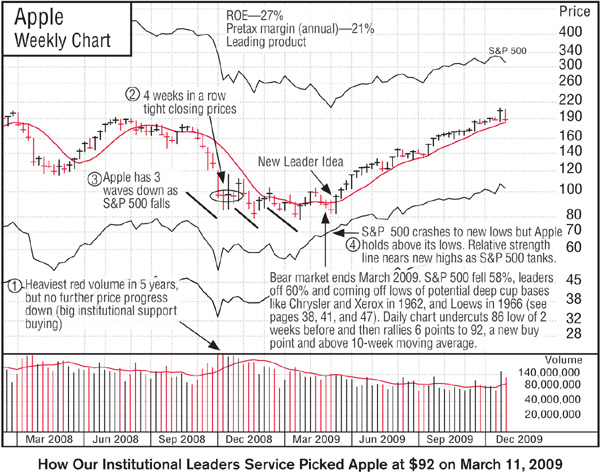

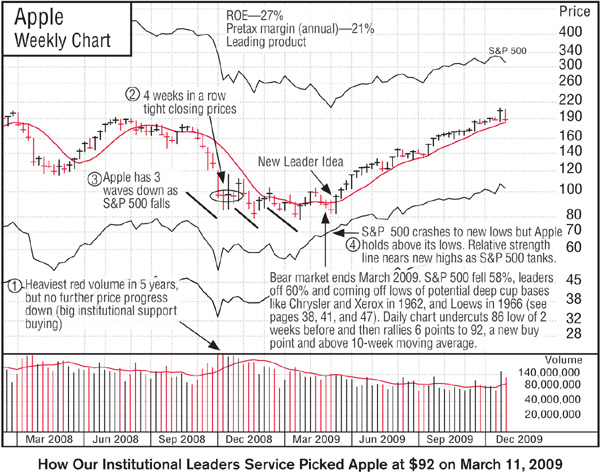

The best way to measure a stock’s supply and demand is by watching its daily trading volume. This is uniquely important. It’s why Investor’s Business Daily’s stock tables show both a stock’s trading volume each day and the percentage volume is above or below the stock’s average daily volume in the last three months. These facts, plus a proprietary rating of the amount of recent accumulation or distribution in the stock, are key information available in no other daily publication, including the Wall Street Journal.

When a stock pulls back in price, you typically want to see volume dry up at some point, indicating there is no further selling pressure. When the stock rallies in price, in most situations you want to see volume rise, which usually represents buying by institutions, not the public.

When a stock breaks out of a price consolidation area (see Chapter 2 on chart reading of price patterns of winning stocks), trading volume should jump 40% or 50% above normal. In many cases, it will be 100% or more that day, indicating solid buying and likely further price increases. Using daily, weekly, and monthly charts helps you analyze and interpret a stock’s price and volume action.

You should analyze a stock’s base pattern week by week, beginning with the first week a stock closes down in a new base and continuing each week until the current week, where you think it may break out of the base. You judge how much price progress up or down the stock made each week and whether it was on increased or decreased volume from the prior week. You also note where the stock closed within the price spread of each week’s high and low. You do both a week-by-week check and evaluate the pattern’s overall shape to see if it is sound and under accumulation or if it has too many defects.

Any size capitalization can be bought using the CAN SLIM system. But small-cap stocks will be a lot more volatile. From time to time, the market shifts emphasis from small to large caps. Companies buying back their stock in the open market and showing stock ownership by management are preferred.