It takes big demand to push up prices, and by far the biggest source of demand for stocks is institutional investors, such as mutual funds, pension funds, hedge funds, insurance companies, large investment counselors, bank trust departments, and state, charitable, and educational institutions. These large investors account for the lion’s share of each day’s market activity.

Institutional sponsorship refers to the shares of any stock owned by such institutions. For measurement purposes, I have never considered brokerage research reports or analyst recommendations as institutional sponsorship, although a few may exert short-term influence on some securities for a few days. Investment advisory services and market newsletters also aren’t considered to be institutional or professional sponsorship by this definition because they lack the concentrated or sustained buying or selling power of institutional investors.

A winning stock doesn’t need a huge number of institutional owners, but it should have several at a minimum. Twenty might be a reasonable minimum number in a few rare cases involving small or newer companies, although most stocks have many, many more. If a stock has no professional sponsorship, chances are that its performance will be more run-of-the-mill, as this means that at least some of the more than 10,000 institutional investors have looked at the stock and passed over it. Even if they’re wrong, it still takes large buying volume to stimulate an important price increase.

Diligent investors dig down yet another level. They want to know not only how many institutional sponsors a stock has, but whether that number has steadily increased in recent quarters, and, more important, whether the most recent quarter showed a materially larger increase in the number of owners. They also want to know who those sponsors are, as shown by services reporting this information. They look for stocks that are held by at least one or two of the more savvy portfolio managers who have the best performance records. This is referred to as analyzing the quality of sponsorship.

In analyzing the recorded quality of a stock’s institutional sponsorship, the latest 12 months plus the last three years of the investment performance of mutual fund sponsors are usually most relevant. A quick and easy way to get this information is by checking a mutual fund’s 36-Month Performance Rating in Investor’s Business Daily. An A+ rating indicates that a fund is in the top 5% in terms of performance. Funds with ratings of B+ or higher are considered the better performers. Keep in mind that the rating of a good growth stock mutual fund may be a little lower during a bear market, when most growth stocks will definitely correct.

Results may change significantly, however, if key portfolio managers leave one money-management firm and go to another. The leaders in the ratings of top institutional mutual funds generally rotate and change slowly as the years go by.

Several financial services publish fund holdings and the investment performance records of various institutions. For example, you can learn the top 25 holdings of each fund plus other data at Morningstar.com. In the past, mutual funds tended to be more aggressive in the market. More recently, new “entrepreneurial-type” investment-counseling firms have cropped up to manage public and institutional money.

As mentioned earlier, it’s less crucial to know how many institutions own a stock than to know which of the limited number of better-performing institutions own a stock or have bought it recently. It’s also key to know whether the total number of sponsors is increasing or decreasing. The main thing to look for is the recent quarterly trend. It’s always best to buy stocks showing strong earnings and sales and an increasing number of institutional owners over several recent quarters.

A significant new position taken by an institutional investor in the most recently reported period is generally more relevant than existing positions that have been held for some time. When a fund establishes a new position, chances are that it will continue to add to that position and be less likely to sell it in the near future. Reports on such activities are available about six weeks after the end of a fund’s three- or six-month period. They are helpful to those who can identify the wiser picks and who understand correct timing and proper analysis of daily and weekly charts.

Many investors feel that disclosures of a fund’s new commitments are published too long after the fact to be of any real value. But these individual opinions typically aren’t correct.

Institutional trades also tend to show up on some ticker tapes as transactions of from 1,000 to 100,000 shares or more. Institutional buying and selling can account for up to 70% of the activity in the stocks of most leading companies. This is the sustained force behind most major price moves. About half of the institutional buying that shows up on the New York Stock Exchange ticker tape may be in humdrum stocks. Much of it may also be wrong. But out of the other half, you may have several truly phenomenal selections.

Your task, then, is to separate intelligent, highly informed institutional buying from poor, faulty buying. This is hard at first, but it will get easier as you learn to apply and follow the proven rules, guidelines, and principles presented in this book.

To get a better sense for what works in the market, it’s important to study the investment strategies of a well-managed mutual fund. When reviewing the tables in Investor’s Business Daily, look for growth funds with A, A–, or B+ ratings during bull markets and then call to obtain a prospectus. From the prospectus, you’ll learn the investment philosophy and techniques used by the individual funds as well as the type and caliber of stocks they’ve purchased. For example:

• Fidelity’s Contrafund, managed by Will Danoff, has been the best-performing large, multibillion-dollar fund for a number of years. He scours the country and international equities to get in early on every new concept or story in a stock.

• American Century Heritage fund uses computers to find stocks with accelerating percentage increases in recent sales and earnings.

• Ken Heebner’s CGM Focus and CGM Mutual have both had superior results for many years. His Focus fund concentrates on 20 to 100 stocks at one time. This makes it more volatile, but Ken likes to make big sector bets that in most cases have worked very well for him.

• Jeff Vinik was a top-flight manager at Fidelity who left and started what is regarded as one of the country’s best-performing hedge funds.

• Janus 20, headquartered in Denver, runs a concentrated portfolio of fewer than 30 growth stocks.

Some funds buy on new highs; others buy around lows and may sell on new highs. New fund leaders can emerge over time.

It’s possible for a stock to have too much institutional sponsorship. Overowned is a term we coined in 1969 to describe stocks in which institutional ownership has become excessive. The danger is that excessive sponsorship might translate into large potential selling if something goes wrong at the company or if a bear market begins.

Janus Funds alone owned more than 250 million shares of Nokia and 100 million shares of America Online, which contributed to an adverse supply/demand imbalance in 2000 and 2001. WorldCom (in 1999) and JDS Uniphase and Cisco Systems (in 2000 and 2001) were other examples of overowned stocks.

Thus, the “Favorite 50” and other widely owned institutional stocks can be poor, risky prospects. By the time a company’s strong performance is so obvious that almost all institutions own the stock, it’s probably too late to climb aboard. The heart is already out of the watermelon.

Look how many institutions thought Citigroup should be a core holding in the late 1990s and 2000s. At one point during the 2008 bank subprime loan and credit crisis, the stock of this leading New York City bank got down to $3.00 and later $1.00. Only two years earlier it was $57. This is why, since its first edition, How to Make Money in Stocks has always had two detailed chapters on the subject of when to sell your stock. Most investors have no rules or plan for when to sell. That is a serious mistake. So get realistic.

Another case was American International Group. In 2008, AIG had more than 3,600 institutional owners when it tanked to 50 cents from the over $100 it had sold for in 2000. The government-sponsored Fannie Mae collapsed to less than a dollar during the same financial fiasco.

America Online in the summer of 2001 and Cisco Systems in the summer of 2000 were also overowned by more than a thousand institutions. This potential heavy supply can adversely affect a stock during bear market periods. Many funds will pile into certain leaders on the way up and pile out on the way down.

Some stocks may seem invincible, but the old saying is true: what goes up must eventually come down. No company is forever immune to management problems, economic slowdowns, and changes in market direction. Savvy investors know that in the stock market, there are few “sacred cows.” And there are certainly no guarantees.

In June 1974, few people could believe it when William O’Neil + Co. put Xerox on its institutional avoid or sell list at $115. Until then, Xerox had been one of the most amazingly successful and widely held institutional stocks, but our data indicated that it had topped and was headed down. It was also overowned. Institutional investors went on to make Xerox their most widely purchased stock for that year. But when the stock tumbled in price, it showed the true condition of the company at that time.

That episode called attention to our institutional services firm and got us our first major insurance company account in New York City. The firm had been buying Xerox in the $80s on the way down until we persuaded it that it should be selling instead.

We also received a lot of resistance in 1998 when we put Gillette, another sacred cow, on our avoid list near $60 before it tanked. Enron was removed from our new ideas list on November 29, 2000, at $72.91, and we stopped following it. (Six months later it was $45, and six months after that it was below $5 and headed for bankruptcy.)

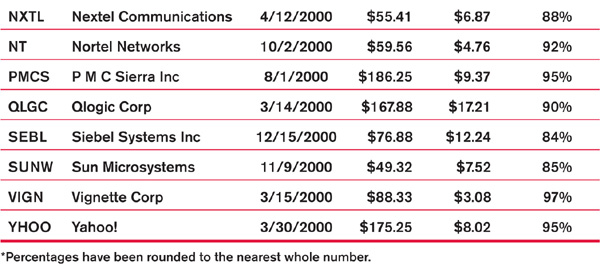

A list of some of the technology stocks that were removed from our New Stock Market Ideas (NSMI) institutional service potential new ideas list in 2000, when most analysts were incorrectly calling them buys, appears on page 198. The lesson: don’t be swayed by a stock’s broad-based popularity or an analyst advising investors to buy stocks on the way down in price.

Another benefit to you as an individual investor is that institutional sponsorship provides buying support when you want to sell your investment. If there’s no sponsorship, and you try to sell your stock in a poor market, you may have problems finding someone to buy it. Daily marketability is one of the big advantages of owning high-quality stocks in the United States. (Real estate is far less liquid, and sales commissions and fees are much higher.) Good institutional sponsorship provides continuous liquidity for you. In a poor real estate market, there is no guarantee that you can find a willing buyer when you want to sell. It could take you six months to a year, and you could sell for a much lower price than you expected.

Stocks Removed from NSMI Buys in 2000

In summary: buy only those stocks that have at least a few institutional sponsors with better-than-average recent performance records and that have added institutional owners in recent quarters. If I find that a stock has a large number of sponsors, but that none of the sponsors is on my list of the 10 or so excellent-performing funds, in the majority of cases I will pass over the stock. Institutional sponsorship is one more important tool to use as you analyze a stock for purchase. From your list of most savvy funds, check to see what were the two or three stocks each one put the most dollars into in the most recent quarter. You might get one or two names to research. Just make sure these prospects pass the critical CAN SLIM rules and the chart is in the right position to buy before you act.