The operation was given the codename Flipper, and Laycock and Keyes drew up the plan at AHQ in the first week of November. The party was divided into four detachments: No. 1 party, comprising Lt-Col Keyes with two officers and 22 other ranks, on HMS Torbay; No. 2 party, comprising Lt D. Sutherland with 12 other ranks, on HMS Talisman; No. 3 party, comprising Lt Chevalier with 11 other ranks, also on Talisman; and HQ party, comprising Col Laycock with two other ranks and a medical orderly, on Torbay. There were also two Senussi guides for Nos 1 and 2 parties, and a folboat party of two officers and two other ranks.

The wreckage of a British Matilda tank following fierce fighting during Operation Crusader in November 1941, the aim of which was to retake the eastern coastal regions of Cyrenaica. To complement the operation, Gen Auchinleck authorized two special-forces raids: Keyes’ operation and the first SAS mission, led by David Stirling. (Cody Images)

The one curiosity of the operational plan for Flipper that has never been adequately explained was the presence of Col Laycock, seen here in 1943 as a major-general. Why would the commander of the Middle East Commando imperil himself by going on such a risky operation, even if he was to remain on the landing beach with the HQ party as an ‘observer’? Was it, in the event of Rommel being captured, to relieve the young Geoffrey Keyes of the emotional pressure of deciding the fate of the German general? In other words, had Laycock nominated himself as Rommel’s actual assassin? (IWM TR 1425)

Four objectives were outlined. These were: (No. 1 party) Rommel’s house and the German HQ, believed to be at Beda Littoria; (No. 2 party) the Italian HQ at Cirene; (No. 3 party) the Italian Intelligence Centre at Apollonia; (HQ party) to act as a report centre and rear link. In addition to the tasks specified in the ‘Operation Order and Plan’, Haselden would destroy the telephone and telegraph communications on the road from Lamluda to El Faidia.

If all went according to plan, then the four raiding parties were to lie up during 15 November and move to other concealed lie-up locations halfway to their targets during the night of 15/16 November. They would lie up the following day, move closer to the targets during the night of the 16/17th, and observe the objectives during the daylight hours of 17 November. The simultaneous attacks would then be launched at 2359hrs on 17 November, a few hours before Operation Crusader commenced.

Once the raiders had carried out their objectives, they would head back to the landing beach at Chescem el-Kelb, where the submarines would be waiting to collect them from the fourth to the sixth nights after landing. Torbay would be off Chescem el-Kelb and Talisman 3 miles to the west. The two vessels were both T-submarines, launched in early 1940, and capable of a maximum speed of 9 knots submerged. Skipper of Torbay was Lt-Cdr Anthony ‘Crap’ Miers, a controversial figure who had been reprimanded by the Royal Navy after admitting in an official report on the sinking of an enemy ship that he had surfaced and ‘with the Lewis gun accounted for the soldiers in the rubber raft to prevent them from regaining their ship’ (Ziogaite et al. 1999). Even so, Miers was recognized as being a brilliant commander who had dispatched a dozen enemy vessels since arriving in the Mediterranean; he would be awarded the Victoria Cross in March 1942 for a daring attack against German shipping in the South Corfu Channel.

In Alexandria, the training intensified, with Keyes and his men continuing to practise their seafaring skills from the depot ship HMS Medway. ‘The hardest bit by far was finding the submarine again when we paddled back out to sea [in rubber dinghies],’ recalled Sgt Cyril Feebery, a member of the SBS’s folboat section. ‘You had to make allowances for those same currents on the Folboat. Then there was the wind. Inflatable dinghies skid about like bubbles in the lightest breeze even with large men aboard’ (Feebery 2008: 37).

Keyes, meanwhile, was finalizing his raiding party. Having decided to take one of his two Commando troops (approximately 53 men), he then enlisted two Senussi guides from the Libyan Arab Force, men handpicked by Capt Haselden, as well as an interpreter – Cpl Abshalom Drori, a Palestinian Commando. Keyes wasn’t at all what Drori was expecting when he arrived in Alexandria. ‘I was surprised to encounter a tall young man in shorts who smiled at me, offered me a seat and asked me some questions about my abilities as a linguist,’ recalled Drori. Once he was accepted as the unit’s interpreter, Drori took the chance to observe the Commandos in the final stages of their training and noted that ‘Keyes never gave an order, he just used to talk to the men, and they always fulfilled his instructions as a matter of course as if they were doing it on their own account’.

The SBS camp at Athlit, on the coast approximately 8 miles south of Haifa in Palestine, was an ideal location for the Commandos. Here the likes of David Sutherland and Tommy Langton had helped to turn the unit into one of the deadliest of all World War II special forces. (SAS Regimental Archive)

Among the officers selected for the mission by Keyes was Capt Robin Campbell, a 29-year-old with an artistic bent whose father, Sir Ronald, was the British Ambassador to Portugal, having fulfilled a similar function in France from 1939 to 1940. Campbell had been a member of Layforce, but since its disbandment had worked at a desk job in Cairo; Keyes chose him not because of his soldiering skills, but because he was fluent in German. Similarly inexperienced in Commando warfare was Lt Roy Cooke of The Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Regiment, who found that though Keyes was the younger man ‘he had the personality to leave me feeling rather like a schoolboy does to his First Fifteen Captain’.

At midday on 10 November Keyes paraded his men and informed them they would be sailing for their destination in two hours’ time. None of them yet knew where or what their intended objective would be. In the two hours prior to embarkation Keyes made two decisions that illustrated his naivety about the nature of the mission and what it would entail. One of his men, L/Cpl Frank Varney, after suffering from sore feet for a number of days, had gone to see the medical orderly, an ex-circus performer who thought neat iodine cured most ailments. The ointment stripped the skin from Varney’s feet and prompted Keyes to remove him from the raiding party. Varney begged to be taken, however, telling Keyes that he wouldn’t be ‘able to look the other chaps in the face if I didn’t go as it would look as if the injury was purposely done’. Keyes relented, and Varney and his painful feet boarded the submarine. So, too, did another brave soldier who convinced Keyes that his dysentery was of the mild strain and would soon disappear.

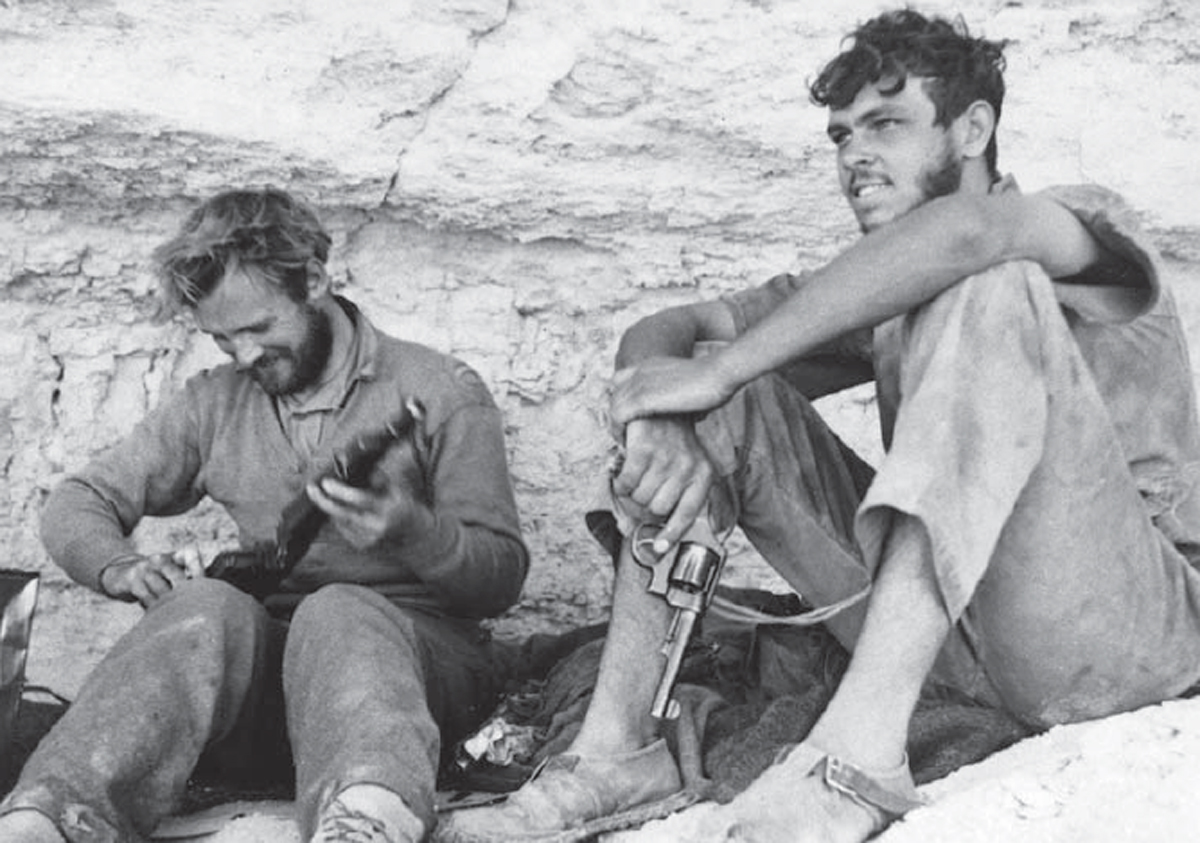

Graham Rose (left) and Jimmy Storie, two original members of the SAS, prepare for another mission deep behind enemy lines in 1942. Like Keyes and Campbell, most of the early SAS had served in Layforce before its disbandment in the summer of 1941. (SAS Regimental Association)

The raiders were two hours late in embarking and it wasn’t until 1600hrs that Lt-Col Keyes, Capt Campbell and Lt Cooke, together with 25 other ranks (ORs), boarded HMS Torbay. The other half of the raiding party, including Col Laycock, Capt Ian Glennie – who had fought with No. 11 (Scottish) Commando at Litani River – and Lt Sutherland, stowed themselves on HMS Talisman, which was commanded by Capt Michael Willmott. Among the men were six soldiers from the SBS – Lt Ken ‘Tramp’ Allot, Sgt Cyril Feebery, Lt Bob Ingles, Lt Tommy Langton, Cpl Clive Severn and a sixth man whose identity is not known. Their role in the operation was to paddle ashore in their folboats and ensure the coast was clear prior to the main landing.

Lt David Sutherland, seen here at his wedding in 1946, had been in the same house as Geoffrey Keyes at Eton, and the pair were reunited in the Middle East. Sutherland was one of the raiders on Talisman who would be unable to land because of the stormy conditions. (Author’s Collection)

Sutherland, who had just turned 21, knew Keyes from Eton and was another of the well-connected young Commando officers who found themselves at a loose end in the Middle East in the summer of 1941. The pair had been in the same house at Eton and though Keyes was Sutherland’s senior by three years they ‘used to sit around comfortably in the Cecil Hotel on the Corniche in Alexandria and wait for news’ (Sutherland 1998: 46). In between whisky and sodas at the Cecil Hotel, Sutherland had used his time in the Middle East wisely, taking a demolition course at Geneifa and becoming an accomplished kayaker. It was in return for instructing Keyes’ Commandos in demolition techniques that Sutherland had been accepted onto the raiding party.

Just a few hours into the voyage, however, Sutherland regretted his role in the operation. ‘It was like Dante’s inferno,’ he recalled of the conditions inside Talisman. ‘We were unbelievably crowded and hot, bodies lying everywhere’ (Sutherland 1998: 47). In addition to the raiders, each submarine also held arms and ammunition, rations, seven rubber dinghies and two folboats. Men slept where they could, some on the wardroom floor and others squeezed into the torpedo tubes. The only relief from the claustrophobia was at night when the submarines surfaced and the soldiers gulped in the fresh air.

Two days out from Alexandria, Keyes and Laycock revealed the exact nature of the operation to the men. Their mission, explained Keyes, was ‘to get Rommel’. With the men fully briefed, Keyes suggested they might want to write to their families, just in case. He then sat down and composed two letters, the first to the woman he loved, who had recently informed him she was marrying another man. Having congratulated the woman on her impending marriage, Keyes wrote:

I am on my way to do more dirty work at the Crossroads. It is by no means an easy task, it is my show, my men, and my responsibility. The chances of getting away with it are moderately good, but if you get this letter, it means I have made a bit of a bog, and not got back.

LRDG and SAS personnel pose for a photograph at one of their desert hideouts deep behind enemy lines. It was from one of these that Capt John Haselden set out to meet the raiding party at the beach. (SAS Regimental Museum)

To his family Keyes wrote in a similar vein, initially, at least, telling them: ‘If this thing is a success, whether I get bagged [captured] or not, it will help the cause.’ But then he let slip his apprehension when he wrote: ‘It may be perfectly alright, in which case this won’t be posted, but I am not happy about the future really.’

As Torbay and Talisman sailed towards the beach at Chescem el-Kelb, Capt Haselden was once more making his way towards the village of Slonta and a rendezvous with Hussein Taher, the tribal elder. Haselden had set out with the LRDG from Siwa Oasis on 7 November; after the LRDG dropped him at the southern end of the wadi Heleigma, he continued on foot to Slonta, arriving on the night of 13 November. ‘He asked me to help him to get two men to go with him,’ said Hussein Taher, recalling Haselden’s arrival at his house. The British officer also requested a horse, explaining it was for an ‘important mission’. ‘When dawn came I had everything needed and he left’. Haselden rode north towards the landing beach and sat down to await the arrival of the raiders.

Torbay and Talisman arrived off the coast of Cyrenaica on the evening of 14 November and submerged for a periscope reconnaissance of the landing beach at Chescem el-Kelb. In Lt-Cdr Miers’ view the weather was ‘ideal for carrying out the intended operations, but owing to overriding military considerations the opportunity was not accepted’ (quoted in PRO 2001: 288). Instead, the two vessels remained at sea during the night and on the morning of 15 November an Italian Caproni Ca.309 Ghibli aircraft was spotted flying low over the coast in the direction of the Talisman and Torbay. The submarines dived to avoid detection and in doing so only partially received a signal. According to Miers the garbled signal was a cause of concern, with Keyes anxious that it might have been an order to abort the operation, but when the signal was sent a second time it proved to be confirmation of the landing date.

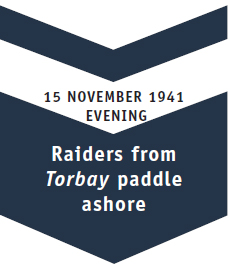

The weather deteriorated throughout the day on 15 November, with a strong wind agitating the sea and a driving wind reducing visibility. Nevertheless, Miers decided ‘in view of the importance of the operation, the eagerness of the military to be landed and the improbability of the weather improving in the next few days, to effect the disembarkation in the prevailing conditions’ (quoted in PRO 2001: 288). In fact, Torbay’s log noted that the wind was Force 4 at midnight, increasing gradually to Force 7.

Torbay closed the beach at 1900hrs as the SBS soldiers scanned the shore through the rain. ‘There was one moment none of us will ever forget. It was as we were closing the beach in Torbay,’ recalled Lt Tommy Langton. Langton was a special-forces veteran, an officer in the Irish Guards who had joined No. 8 Commando before it was subsumed into Layforce. A double rowing blue for Cambridge in the late 1930s, Langton was, recalled David Sutherland, ‘one of the most powerful swimmers I have ever seen’ (Sutherland 1998: 40). Langton continued:

We were on the forward casing of the submarine, blowing up the dinghies and generally preparing. We could just see the dark coast line ahead. We had been told that Haselden would be there to meet us, but I think no one really believed that he would. He had left Cairo quite three weeks before, and during the interval there had been several changes of plan... When the darkness was suddenly stabbed by his torch, making the looked for signal, there was a gasp of amazement and relief from everyone – in other circumstances it would undoubtedly have been a spontaneous cheer. (www.combinedops.com)

The beach at Chescem el-Kelb, where the raiders landed on the night of 15 November. The sea conditions were so bad that HMS Talisman would be unable to land 18 of its Commandos, leaving Keyes with only 36 men to carry out his mission. (Photograph courtesy Steve Hamilton – Western Desert Battlefield Tours)

Once Miers had confirmed the signal, at 1956hrs Lt Ingles and Cpl Severn launched their folboat into a heavy swell and began paddling towards the beach. Having contacted Haselden on the beach, Ingles and Severn waited for the first of the Commandos to paddle ashore. However, by now Torbay was experiencing difficulty in manoeuvring in the rough seas. Also finding the conditions a challenge were the raiders, who had been busy passing up the rubber dinghies through the forward hatch and inflating them on the deck of the submarine with a foot pump. A solitary wire ran fore and aft on Torbay ‘and the men, who were lined up two by two on the forward casing, had to hold on to this with one hand and prevent their dinghies sliding off the deck with the other’.

Initially all went well, but when Torbay trimmed down in readiness for the launch of the dinghies a large wave crashed over the casing, sweeping the four aftermost rubber boats into the sea along with Cpl Spike Hughes, a 40-year-old former postman from London. ‘I can’t swim much!’ cried Hughes, as he disappeared underneath the black foam of the Mediterranean. Luckily for Hughes, at the moment the wave hit, he had just finished inflating his two Mae West life jackets. ‘I grabbed hold of a dinghy, clambered in, caught another one and tied the two together and felt quite safe,’ recounted Hughes. ‘One dinghy is difficult enough to handle, two together are hopeless. I could see the sub, but the more I paddled the further I seemed to drift away. After what seemed an hour, but which may have been only a few minutes, the current took me near the sub. I called out and they threw me a rope’. Hughes had indeed been in the water for a short time, but by the time he had been rescued, and the dinghies recovered, Torbay was obliged ‘to go West for two miles to get back to her previous position’ (PRO 2001: 288).

Concerned by the unexplained delay, Ingles and Severn had paddled back from the beach, arriving at Torbay at 2155hrs, just as the raiders tried once more to launch their rubber dinghies into the treacherous seas. The first seven dinghies were launched but then an eastward drift again disrupted the disembarkation, so that it wasn’t until 2240hrs that launching was resumed. Miers was becoming agitated by the delays, writing in his report that ‘perhaps the less well trained soldiers were being launched – at any rate boats capsized again and again, and in several cases the gear (boots, blankets, shirt and rations wrapped up in an anti-gas cape) was lost overboard’ (PRO 2001: 289). The gear was sealed in a watertight container that was attached to the underside of the rubber dinghy.

The SBS party was also suffering at the hands of the sea, one wave smashing Ingles’ unoccupied folboat against the side of the submarine and breaking it in two. To counter the conditions, Miers manoeuvred his submarine close to the spit at the end of the bay so that Torbay was in a slight lee by midnight.

After Capt John Haselden guided the raiding party ashore on the night of 15 November the bedraggled Commandos huddled round a campfire inside one of the ruined houses to the east of the beach. This photograph shows the renovated houses at Chescem el-Kelb in 2012. (Photograph courtesy Steve Hamilton – Western Desert Battlefield Tours)

The last dinghy to be launched caused the most problems, capsizing three times before finally it got clean away at 0030hrs on 16 November, with the two Commandos paddling for the shore undaunted. It had been a trying few hours for all concerned, and even an experienced and pugnacious commander such as Miers found the experience testing. He was full of praise for his submariners, as he was for the Commandos, writing:

Those of the crew who took part received a very severe buffeting while handling the boats alongside in the swell and nearly all of them were completely exhausted at the finish. No less splendid was the spirit of the soldiers under strange and even frightening conditions. They were quite undaunted by the setbacks experienced, and remained quietly determined to get on with the job. (PRO 2001: 289)

Once ashore, Keyes and his Commandos were led by Haselden to one of a scattering of ruined houses a couple of hundred yards from the beach, where they stripped off their wet clothes and warmed themselves round a fire, a mug of hot tea in each man’s hands. A few then got their heads down for a short rest while others waited to greet the second party from Talisman. Miers signalled to Talisman at 0035hrs that the operation was completed before Torbay put out to sea to transmit a message from Haselden to Eighth Army and to report the successful completion of the first raiding party to the wireless station in Rosyth, Scotland.

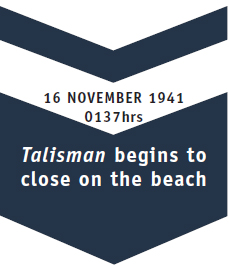

The message from Torbay was gratefully received on board Talisman, where Laycock had been mystified by the delay. Becoming ever more fretful as the evening wore on, Laycock ordered Lt John ‘Farmer’ Pryor of the SBS to get in his folboat and find out what was the matter. Pryor was pretty sure he could make out Torbay’s conning tower as he and his No. 2, Cpl John Brittlebank of the Royal Artillery, climbed into their kayak. ‘When it came to going up and down from sea-level, damned if I could find the Torbay,’ recalled Pryor. ‘And after ten minutes or so fruitless paddle [sic] returned to the Talisman and said I couldn’t find her.’ Capt Willmott, skipper of Talisman, pointed his submarine straight at Torbay and told Pryor all he had to do now was paddle in a straight line. ‘I did so but still didn’t find her,’ recalled the SBS officer. ‘However I came across a rubber dinghy with two Glaswegians in it, who said that they were the last dinghy of the Torbay and they “hoped to get ashore some time” … I went back to Captain Willmott and told him this’.

Minutes after the return of Pryor from his abortive attempt to establish contact with Torbay, Willmott received the signal from Miers informing him that his half of the raiding party had been landed successfully. Willmott immediately instructed Pryor to paddle to shore and stand on the beach with a flashlight and signal the letter ‘C’, whereupon the Commandos would launch their dinghies. ‘I set off to do this,’ recalled Pryor:

The Torbay party by this time had met Haselden and the venerable Arab he had with him. As there were no Italians about they had lit a fire in a ruined house on the beach, round which the men were trying to dry themselves. Seeing the fire I paddled for it, and it drew me too far to the east. Before I could stop we were capsized in surf on the rocks. We hung on to the canoe [sic], as we didn’t want to have the wreckage about, and managed to struggle on to the rocks, but kept being sucked off by the undertow and knocked over by the waves.

Abandoning the kayak on the advice of Brittlebank, Pryor and his companion swam into a little rectangular bay, staggering ashore close to where the men of Torbay were warming themselves round the campfire. Pryor told Brittlebank to get dry and then ‘stood miserably cold flashing C–C–C for a long time. I found I was slightly less cold without my shirt and stood naked C–C–Cing’. Geoffrey Keyes and Roy Cooke joined the shivering spectacle on the beach and laughed at Pryor’s plight.

Keyes’ high spirits weren’t matched on board Talisman, where Capt Willmott was confronted with an awkward decision. The length of time it had taken the Commandos from Torbay to land had eaten considerably into his launch window; now he had just 3½ hours to get his 25 raiders safely onto the beach. On the plus side, however, the wind had dropped and the sea was less troublesome. At 0137hrs Talisman began to close on the beach, but eight minutes later, just as the first dinghy was about to be launched, ‘the ground swell increased without warning’ as the vessel touched the ocean floor. A wave reared up over the submarine, crashing down on the casing and sweeping away seven of the eight boats and 11 men.

Moments before, David Sutherland and Robert Laycock had been sitting in their dinghies discussing the stars above them. ‘We were just talking about the Pole Star and its importance in navigation when the Talisman ran aground on the beach,’ remembered Sutherland. ‘A green sea swept over the forecasing from behind us and I saw Robert Laycock’s jaw tighten as he and his companion were hurled headlong into the boiling water. Luckily I had both arms over the steel jumper wire that runs along the forecasing’ (Sutherland 1998: 48).

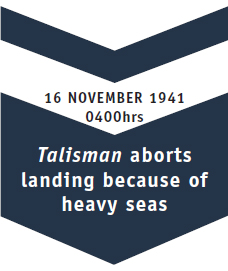

To escape the swell Willmott was forced to go astern into deeper water and dispatch one of the SBS’s folboats to help in the rescue of the men. The folboat, containing Ken Allott, was smashed by the vindictive sea as it was being launched, leaving Willmott with no option but to order Sutherland ‘to throw in the remaining boats clear of the submarine and get his men to jump in after them. The men very pluckily carried out this order, but only one boat got away the right way up with the men on board’ (PRO 2001: 289). For the next two hours Talisman plucked men and dinghies from the sea, but by the time the search-and-rescue mission was complete it was 0400hrs and the moon was up. In addition, one of the submarine’s hydroplanes had been damaged and its batteries needed recharging. Only ten men had been launched from the Talisman, among them Laycock, leaving 18 raiders still on board the submarine – one Commando, L/Cpl Peter Barrand of the London Rifle Brigade, drowned during the attempted landings, despite the fact he had been wearing two Mae Wests when his body washed ashore.

Once Laycock reached the beach he signalled to Talisman with an electric torch, informing Willmott they would hide the boats while requesting they collect those ones still adrift. Astonishingly, Keyes hadn’t brought any skilled signallers with him, because all the Commandos trained in this art had been transferred to other regiments following the disbandment of Layforce. He had had time, nevertheless, to recruit a proficient signaller for the mission but instead relied on Laycock’s slipshod skills. Though he had taken a crash course in signalling, the colonel’s signals were often misunderstood, a state of affairs not helped by the fact he had only a standard torch with no signalling key.

While Haselden’s Arab companion led the Commandos to a cave where the rubber dinghies were stowed, the raiders swept the beach of all incriminating evidence of their presence. For an hour or so before dawn, Keyes paced the beach in the hope of spotting some stragglers from Talisman (which had now submerged and was recharging its battery). But he saw none, and eventually Robin Campbell persuaded his commanding officer to return to the campfire.

‘Just before first light, Keyes gave the order to assemble the stores and personal kit and to follow him inland to a wadi [approximately 1 mile inland], which he had previously selected from the map as a good place to lie up in during the following day,’ recalled Campbell, who said Pryor and Brittlebank were detailed to remain on the beach. ‘The men were dispersed in various old ruined houses and caves all round the bed of the little dry stream, where they huddled together and slept – as cold as charity’.

Keyes had with him 36 men in total, around three-quarters of his original fighting force, but they were also short of much vital equipment – including rations and ammunition. Throughout the morning Keyes, in consultation with Laycock, modified the plan of attack in light of the previous night’s events. There were now to be just two raiding parties, rather than the four originally anticipated. No. 1 Detachment, under the command of Keyes and comprising Capt Campbell and 17 ORs, was to attack the villa used by Rommel and the German HQ at Beda Littoria. No. 2 Detachment, led by Lt Roy Cooke and consisting of six ORs, was to attack the Italian HQ at Cirene. This had been the intended target for David Sutherland, the demolitions expert, but neither he nor most of his explosives had made it ashore. As already arranged, Haselden was to cut communications on the road from Lamluda to El Faidia, while Laycock was to remain at the rendezvous with a sergeant and two ORs. Their job was to guard the stores and collect any more Commandos who might come ashore from Talisman (in fact, none did, as the weather failed to improve in the next 24 hours, compelling Miers to instruct Willmott not to try to land any more Commandos). It was also decided that on their return from the raid, the Commandos would rally at the rendezvous 1 mile inland, and not on the beach. Once Keyes was satisfied with the amended plan he summoned his men and, according to Campbell:

… after explaining the new plan in outline, supervised the opening, repacking and distribution of the ammunition, explosives and rations. Although his original plan had been very thoroughly upset and his force lacked guides, two, or it may have been three, officers and some twenty men, Keyes gave no sign of being disturbed by this, and none of the men seemed to realise how seriously hampered the operation was from the outset.