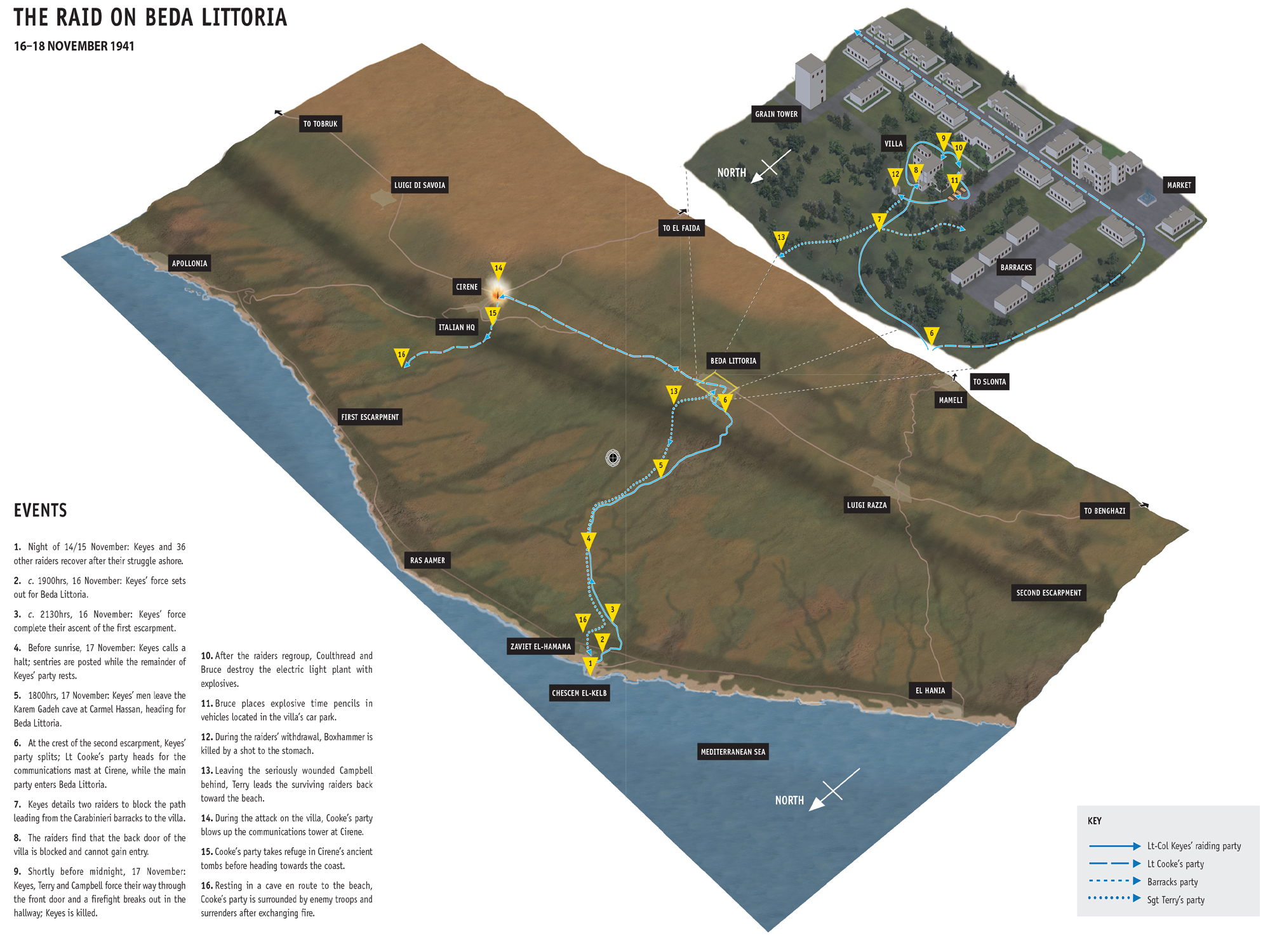

A new plan was in place by the afternoon of 16 November, but Keyes still had the problem of what to do about acquiring guides to lead them 18 miles south to the target at Beda Littoria. The two guides recruited from the Libyan Arab Force had been on Talisman and were presumed to have drowned. Haselden loaned his Arab guide to Keyes, saying he would pick up a replacement from Hussein Taher in Slonta. Haselden then set off across the Jebel el-Akhdar, and shortly after 1900hrs Keyes and his men followed.

The morning of 16 November had been bright and sunny, but it proved to be the calm before another storm descended on the Libyan Desert. By the afternoon the sky was dark and moody, and rain began to fall shortly before dusk, puzzling the raiders, who had been assured in their operational briefings that the weather would be temperate. None of the Commandos wore winter clothing. Instead, most wore civilian clothes under a battledress blouse and trousers with short puttees, and Army-issue boots. The officers carried either .45 Colt automatics or .38 Smith & Wesson revolvers, and the men .45 Thompson submachine guns, and clasp knives and whistles were on the end of lanyards tucked in the breast pocket of their battledress. In the haversacks slung over their shoulders, the men had rations (sardines, salmon, chocolate and fruit salad) as well as spare socks, water bottle, mess tin, hand grenades and sand-coloured lightweight blankets. In addition, most had a pair of crepe-soled plimsolls that were known as ‘sand-creepers’.

Once ashore, Keyes and his depleted raiding party had to negotiate what is known locally as the Jebel el-Akhdar (‘green mountain’ in Arabic). In reality, it was a two-tier escarpment with a sloping shelf of land between the tiers in which lie innumerable gullies and dry riverbeds, as seen in this 2012 photograph. (Photograph courtesy Steve Hamilton – Western Desert Battlefield Tours)

‘None of us had seen cloudy skies or rain for many months,’ recounted Campbell. ‘We had hoped for the usual dry North African weather, since we would have to spend about six days in the open. Whatever he may have felt like inside himself, Keyes certainly appeared confident and cheerful as we set off’. Col Laycock waved off the raiders, remaining behind in the wadi with Lt Pryor and Cpl John Brittlebank of the SBS, and another soldier armed with a Bren gun. Led by the guide, and with Drori the interpreter at his side, Keyes and his men climbed up the first tier of the escarpment and were on the ‘step’ by 2130hrs. ‘All that night we marched inland over extremely difficult going, mostly rock-strewn sheep tracks,’ said Campbell.

Our guide left us about midnight, fearing to go any further in our company. Keyes then had the difficult task of finding the way by the aid of an indifferent Italian map, his compass and an occasional sight of the stars. In spite of this responsibility he kept the heavily laden party going with my help and that of Lieutenant Roy Cooke.

Their progress slowed by the flight of their guide, the raiding party continued their trek south throughout the early hours of 17 November. Shortly before sunrise, Keyes called a halt to the march on top of a small hill marked on his Italian map as ‘Um Girba’. Sentries were posted and the rest of the men covered themselves in their blankets and went to sleep.

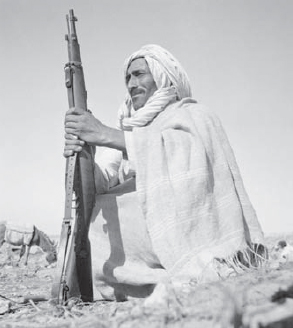

Campbell was woken a couple of hours later by the sound of voices. Crawling out from under his blanket into a soft drizzle, he joined Keyes, who was sitting wrapped in his blanket listening to a breathless Drori explain that they were surrounded by armed Arabs. ‘Raising our heads cautiously above the scrub we saw a few rascally-looking Arabs, one or two brandishing short Italian rifles,’ said Campbell. He continued:

However, Keyes decided that they did not appear either particularly formidable or implacably hostile, so he gave the order for the chief of the band to be brought to him for a talk. Shortly afterwards a villainous-looking Arab, with a red head-cloth wound round his head, was brought up by the Palestinian interpreter and a sentry. Keyes exchanged a few civilities with this seedy brigand, and then began a conversation through the interpreter, asking his help against the hated Italians.

The leader of the band of Arabs was a man called Musa of the Dorsa tribe, who had been alerted to the presence of the Commandos by a local out looking for some stray cows on the morning of 17 November. Keyes took a letter from the pocket of his battledress from Seyed Idris, exiled chief of all the Senussi, and handed it to Musa. He couldn’t read, however, so Drori read out its contents:

In the name of God, the Merciful. To my brethren, Sons of Heroes, People of Libya. The bearers of this letter are working with us, and in the holy cause of our country. Therefore, I bid you all, the people of Libya, who have the opportunity of meeting the bearers of this letter to afford them protection and help with all your strength. We beseech the Almighty that this, your work, may be crowned with victory. We greet you with the blessing of God.

Born at Al Jaghbub, the heartland of the Senussi territory, on 12 March 1889, Idris became Chief of the Senussi in 1916 following the abdication of his cousin Sayyid Ahmed Sharif es Senussi. Chief Idris was a staunch advocate of independence for Cyrenaica and was recognized as Emir of Tripolitania by the Italians in 1922. However, he soon declared war on Mussolini and Italy, fleeing into exile in Egypt from where he launched a campaign of guerrilla warfare against the colonialists.

Upon the outbreak of World War II, Idris offered his support to the British in their war against the Axis Powers in return for a promise of independence once the Italians had been defeated. Senussi tribesmen provided the British with vital intelligence on enemy troop movements and also carried out numerous acts of sabotage and ambushes on German and Italian convoys.

With the Allies victorious in North Africa in 1943, Idris returned to Benghazi, Cyrenaica, and his position as Emir. Following the end of the war Idris was awarded the Order of the Grand Cross of the British Empire in 1946 in recognition of his assistance in defeating the Axis Powers in Libya. In 1951 Idris was crowned King of Libya and 12 years later a revised constitution led to the renaming of his land, the Kingdom of Libya. Always a loyal friend to the British and Americans, King Idris led his country into an era of great prosperity until ill health forced his abdication in September 1969, but before Crown Prince Hasan as-Senussi could accede to the throne, a group of Libyan Army officers under the leadership of Muammar Gaddafi staged a coup and abolished the monarchy. King Idris fled – once more – into exile in Egypt and died there in 1983, aged 94. Gaddafi’s despotic rule ended with his death in 2011.

A Senussi warrior. Having resisted French and Italian colonialism in the years before World War I, the Senussi fought against the British in 1914–18. In World War II, however, the Senussi allied themselves with the British in the face of Italian and German aggression. (IWM E 10186)

The 18-mile approach to the target was over rough and rocky terrain, made worse by one of the worst storms in years that brought with it a torrent of rain. ‘The going became so bad that we were compelled to go in single file to avoid knocking one another over as we slipped and stumbled through the mud,’ recalled Capt Robin Campbell. (Photograph courtesy Steve Hamilton – Western Desert Battlefield Tours)

On hearing what Idris had to say, Musa broke into a broad grin and offered the Commandos whatever help he could. The first thing Keyes asked for was cigarettes, handing over some Italian lire in exchange for some cartons as he explained theirs had been ruined during their landing. Then Keyes got down to business with the leader, explained Campbell:

After prolonged haggling, he [Musa] and Awad Mohammed Gibril of the Masamir tribe, a taller, younger, but equally unprepossessing ruffian, agreed to take the raiders to Rommel’s Head Quarters, which they knew well, for the sum of a thousand Italian lire. They promised that when night fell they would guide the party to a cave within a few hours march of their objective, and in the meantime, for another thousand lire, offered to prepare a kid for them to eat. This offer was accepted thankfully, as the men had nothing hot to eat or drink since they had landed. When it grew dark we fell in and marched off in file, with Keyes and the guides and interpreter at the head.

The raiders marched south, but their progress was interrupted by some shouts away to their flank. Keyes dispatched a scout to see what the hullabaloo was about while they lay on the ground in the darkness. The scout returned and told Keyes he had seen nothing untoward and whoever had been shouting had dispersed. The men pressed on and after nearly three hours, reached a cave called Karem Gadeh at Carmel Hassan. They were now approximately 5 miles north of Beda Littoria. ‘The entrance to the cave went down under a pile of stones and rocks,’ recalled Campbell.

Inside it was fairly roomy and quite dry. Apart from an appalling smell of goats, it was an ideal place to spend the rest of the night and the following day. The roof was blackened by the smoke from generations of goatherds’ fires, and the smell of generations of goats clung to the floor and walls. Keyes decided it would be safe to light a fire inside, so that we passed the rest of the night in a dry and warm though smoky cave.

The guides left the Commandos in the cave with a promise to return before dawn, which they did, warning Keyes that they should soon be on the move because it was a custom of goatherds to bring their flocks to the cave when the weather was bad. Keyes heeded the advice, moving his men to a nearby copse where there was an abundance of cyclamen growing and some arbutus berries, a fruit similar to the strawberry and called the ‘Fruit of God’ by the Senussi. Leaving Campbell in charge of the party, Keyes, together with Sgt Jack Terry and Lt Roy Cooke, went off with one of the guides, called Awad, to spy out the land.

Terry was another veteran of No. 11 (Scottish) Commando, though there was little Scottish about the 20-year-old. Born in Bulwell, Nottinghamshire, he became an apprentice butcher upon leaving school after being turned down by the police force on account of his size. In 1937 he enlisted in the Royal Artillery and was a member of the British Expeditionary Force, being sent to France in the spring of 1940. After being plucked from the beaches at Dunkirk, Terry volunteered for the Commandos and saw action at Litani River.

The account given after the war by the Senussi to Keyes’ sister described how:

In the morning the leader [Keyes] asked Awad to get some Arab clothes so that both he and Awad might go to Beda Littoria in disguise. Awad refused because of the number of enemy spies and agents about and took them to the wood to hide. The leader wanted to examine Beda Littoria through his binoculars but could not do so because they were on low ground.

What Keyes was able to see, however, was the top of the second escarpment, beyond which was the objective, approximately a mile further on. Determined to gather as much intelligence as possible, Keyes persuaded Awad to send his son into Beda Littoria, promising him a reward of some lire if he brought back good information. Not long after the boy had embarked on his espionage mission, a thunderstorm swept in from the coast, bringing with it a deluge of rain. Keyes decided to risk moving the party from the copse back to the cave in order that they should spend the hours preparatory to the attack as dry as possible. The men made themselves as comfortable as they could in the cave and then settled down to wait. Some fed on their rations, tinned salmon and fruit salad, while others cleaned and checked their weapons.

In the afternoon the boy returned from Beda Littoria, bringing with him much valuable information. ‘His report enabled Keyes to draw an excellent sketch map, which proved to be extremely accurate and included such details as the outbuildings, and the park for staff cars,’ said Campbell. ‘He was thus able to give the men a good visual notion of their objective. The boy told him there was a guard-tent in the grounds of the headquarters, but that if it rained the guards would probably all be inside the house’.

The Commandos were issued with the 1st Pattern Fairbairn-Sykes Dagger; this formidable weapon had a 6 in double-edged blade, and has remained an iconic special-forces weapon to this day. (Leroy Thompson)

in double-edged blade, and has remained an iconic special-forces weapon to this day. (Leroy Thompson)

Armed with the precious information, Keyes drew up his final plan of attack, detailing individual tasks to each member of the raiding party. He, Campbell and Terry would enter Rommel’s villa in search of their prey, while three ORs were to disable the electric light plant. Five men were to act as lookouts at the exits from the guard tent and the car park. The rest of the party were dispersed so as to prevent interference by the enemy: two were posted outside the hotel a few hundred yards from the villa to prevent anyone leaving, and another two soldiers were detailed to watch the road on each side of the house. The other two Commandos would guard the entrance used by Keyes to gain access to the villa. Keyes told all of his men that the password challenge would be ‘Island’ to be answered by ‘Arran’.

The loss of the majority of soldiers from Talisman did present a problem to Keyes, however, as he could not address the threat posed by the presence of another barracks half a mile to the south. He did not have enough men to nullify this threat and instead counted on their achieving their aims with such speed that the men from this barracks wouldn’t have time to come to Rommel’s rescue. With this in mind, Keyes modified Cooke’s role in the operation. Instead of leaving the main party on top of the escarpment and heading towards the Italian HQ at Cirene, Cooke and his five men would now accompany Keyes to Beda Littoria and guard the road east of the villa until the moment they heard the first gunfire. Only then were they to strike out east towards their objective.

With each Commando fully briefed on his own role in the impending mission, the men then submitted themselves to a foot inspection. One soldier, Bob Fowler of The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, had trodden on a rusty nail shortly after landing on the beach and his leg was now so swollen that Keyes ordered him to remain in the cave and guard their surplus kit. Before the men enjoyed a final meal of bread and marmalade, they covered their faces in black cork and changed from their boots into their plimsolls. Some of the men slipped canvas ammunition bandoliers under their battledress to keep the sticks of gelignite they contained dry.

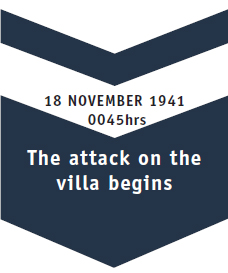

Then, at 1800hrs, they left the cave, Keyes deciding to allow six hours to cover the 5 miles to the target because of the dreadful weather conditions. Throughout the afternoon the rain had fallen in torrents and now the terrain was ankle-deep in mud. ‘Spirits were sinking – I know mine were – at the prospect of a long, cold, wet and muddy march before we even arrived at the starting point of a hazardous operation,’ recalled Campbell.

… it became so dark it was only just possible to see the man in front. We had to hold on to one another’s bayonet scabbards in order to keep in touch. Every now and again a man would fall, and the whole column would have to halt while he picked himself up. From time to time the middle of the column would lose touch with the man in front of him, and we would have to stop and sort ourselves out again. We reached the bottom of the escarpment at about 10.30 p.m. without serious mishap. After a short rest we began our climb of about 500 feet of muddy turf with outcropping rocks. About half way up the noise of a man slipping and striking his tommy gun against a rock roused a watch-dog, and a stream of light issued from the door of a hut as it was flung open about a hundred yards away on our flank. As we crouched motionless, hardly breathing, we heard a man shouting at the dog. Finally the door closed, and we resumed our way upward. At the summit (which is known as Zaidan hill) we found a cart track which the guides said led straight to the back of the German Headquarters. We halted for a rest and Keyes re-formed the men, some twenty-four all told.

A rugged US-manufactured sidearm offering lethal stopping power, the .45-calibre Colt M1911 semi-automatic pistol was a standard-issue weapon employed by the Commandos during World War II. (Leroy Thompson)

Having rested for a few minutes, the raiders pushed off down the cart track with Keyes in the lead, followed by Terry, Drori and the Arabs. Some 50 yards back were Campbell and the rest of the Commandos. As they neared the bottom of the cart track the guides became≈increasingly nervous, telling Drori that they wished to depart, as their job was done. The interpreter told Keyes the men’s concerns, whereupon he took out his revolver and said to Drori: ‘Tell them to go on until I tell them to stop’. Continuing along the cart track, which was muddy but otherwise easily negotiable, the Commandos came to a shrub beside a fork. They were now less than half a mile from Beda Littoria but, despite their proximity to the target, Keyes allowed those who wanted it a final cigarette. Then they moved on, creeping ever closer until they reached the track that led down the slope and towards the rear of the village.

Close by was a solitary cedar tree and here Keyes told Lt Cooke to take his five men and move into position on the main road. Keyes, meanwhile, from his vantage point, called over one of the guides. He could clearly see the imposing grain tower, which rose above the surrounding flat countryside, as well as the six-storey prefecture, but he asked the guide to point out Rommel’s villa and the barracks housing a detachment of the Carabinieri, Italy’s military police.

Approximately 100 yards from the barracks was the suk, the market, separated from it by a barbed-wire fence and a hedge. Cedar and eucalyptus trees lined the road leading through the village towards the prefecture, in front of which was the main square. There was an ornate fountain in the square and a rostrum on one side from which Italian officials frequently harangued the locals. With the exception of the traditional suk, Beda Littoria was a modern village, consisting of buildings constructed by the Italians in the last 20 years.

At this point the guides categorically refused to go any further and Keyes, realizing he had no further need for them, instructed them to return up the track and wait by the cedar tree. They would receive their money once the raid was over. As the guides melted into the darkness, Keyes took Terry on a preliminary reconnaissance of the target. ‘While he was away one of my party tripped over a tin can and roused a dog, which began to bark,’ recounted Campbell.

An Arab in one of the houses also began to scream. After a minute or two an Italian in uniform and an Arab officer of the Italian Libyan Arab Force emerged from one of the huts and approached us, asking who we were and what we were doing there. Drori replied in German saying, ‘We are German troops on patrol. Go away and keep your dog quiet.’ Drori repeated this in Arabic, asking them to quiet the man in the hut, and the Arab officer, believing they were Germans, then spoke to the man who was screaming, addressing him by name and told him to be quiet. Bidding us ‘Gute Nacht’ they disappeared back into their hut apparently satisfied, which the men thought was a great joke.

The Commandos wouldn’t have laughed if they knew that the villa in their sights didn’t in fact contain the top German commander in North Africa. Nor did it even house its usual occupant, Major Schleusener, Rommel’s quartermaster-general, who was in an Apollonia hospital suffering from dysentery, the same hospital in which his deputy, Hauptmann (Captain) Otto, was being treated for inflammation of the lungs. Instead, Hauptmann Weiss was the senior officer in charge on the night of 17/18 November, and under his command were a ‘couple of dozen officers, orderlies, runners, drivers and the usual personnel to be found on a Quartermaster’s staff’.

In fact, Rommel had never used the villa at Beda Littoria as his private accommodation. At the end of July 1941, when he had been given command of the newly formed Panzergruppe Afrika, Rommel had his GHQ in Beda Littoria with Generalmajor Alfred Gause, his chief of staff, and Oberstleutnant Siegfried Westphal, Ia (Operations). Their offices were in the prefecture and the houses close by the impressive white building contained their staff officers.

In August Schleusener took up residency at Beda Littoria and Rommel relocated his HQ to the Gambut landing ground between Tobruk and Bardia, about 200 miles east of the villa. According to Rommel’s aide-de-camp, Heinz Schmidt, the Luftwaffe (German Air Force) garrison at Gambut had ‘transformed an old underground bir [well] into their mess. The ancient cistern was comfortable and bomb-proof, and was completely equipped with ante-room and bar-counter that had been moved from buildings at El Adem’ (Schmidt 1951: 96). The mess was lavishly equipped, with iced drinks, fresh fruit and cigarettes readily available for Rommel and his staff.

The villa at Beda Littoria had ‘been intended to serve as a refuge for Rommel where he could get away from his own staff and the problems of war from time to time’ (Schmidt 1951: 98). The German commander had indeed stayed a night or two at the villa in the past, and Schmidt recalled a convivial dinner at which Rommel, Gause and Marshal Ugo Cavallero, chief of the Italian Supreme Command, had been present.

Not only was Rommel not in the villa on the night of the attack – he wasn’t even in North Africa. He was in Rome, with his wife, having celebrated his 50th birthday two days previously, and on the 17th he and Frau Rommel were at the opera as guests of Generalleutnant Johann von Ravenstein, Rommel’s second-in-command in the desert, who was also enjoying a few days’ rest and recuperation in the Italian capital. According to Schmidt, as they were leaving the opera, Ravenstein asked Rommel if he had enjoyed the performance, to which his superior replied: ‘We must shift those battalions in the Medawwa sector’ (quoted in Schmidt 1951: 98).

At the villa, however, a late-night conference was in progress on the evening of the 17th, chaired by Weiss and attended by an engineer officer and two supply officers named Schulz and Ampt. Security at the villa was lax, understandably, as the Germans were 250 miles behind their own lines. A military policeman called Jamatter ‘kept watch in the corridor below [and] his sole weapon was a bayonet. He was less a guard than a distributor of late-arriving mail’ (Carell 1961: 49). Another soldier, a 20-year-old from Bavaria called Matthew Boxhammer of the quartermaster’s motorized section, was lying on a camp bed in the guard tent (a big bell-tent) and in a workroom on the ground floor of the villa were Leutnant Kaufholz, a liaison officer, plus Feldwebel Leutzen, Unteroffizier Kovacic and another NCO named Bartl. These four men were asleep on makeshift camp beds in the workroom, preferring to billet at the villa rather than in the barracks with their Italian allies.

When Keyes and Terry returned from their reconnaissance Keyes informed Bdr Joe Kearney, Sgt Charlie Bruce and Pte Denis Coulthread – who had been tasked with cutting telephone wires – that there was a change of plan: they were to cover the rear of the villa and kill whoever came or went out of the back door, which Keyes had found to be locked. Keyes ordered the rest of the men to move into their positions, and then a few minutes before midnight he led his raiding party through a hedge and into the garden of the villa. The first task was to eliminate the guard inside the guard tent, Boxhammer. Accounts differ as to how Boxhammer met his end, with German reports describing how he was shot dead at the end of the raid, but Elizabeth Keyes, sister of Geoffrey, wrote that her brother ‘went forward alone and killed the guard’. The fact that Boxhammer was shot in the stomach suggests he was killed while the raiders escaped, when stealth was no longer important.

Unable to force their way through a window, Keyes, Campbell and Terry had to go in through the front door of the villa, seen here in 2012. Campbell, a fluent German-speaker, knocked on the door and demanded entrance – not the best way to launch a guerrilla operation. (Photograph courtesy Steve Hamilton – Western Desert Battlefield Tours)

‘All the ground floor windows were high up and barred with heavy wooden shutters, so it was impossible to get in that way,’ recalled Campbell.

There was no alternative but to use the front door. We followed [Keyes] round the building on to a gravel sweep in front of the house. The front door was set back inside a porch, at the top of a flight of stone steps. Keyes ran up the steps. He was carrying a Colt, and I knocked on the door for him, demanding loudly in German to be let in. The door opened on a second pair of glass doors, and we were confronted by a German.

The German was Jamatter, the military policeman, armed only with a bayonet but a brave bear of a man. ‘Keyes at once closed with him, covering him with his Colt,’ said Campbell.

The man seized the muzzle of Keyes’ revolver and tried to wrest it from him. Before I or Terry could get round behind him he retreated, still holding on to Keyes, to a position with his back to the wall, and his either side protected by the first and second pairs of doors at the entrance. He started to shout. Keyes could not draw a knife and neither I nor Terry could get round Keyes, as the doors were in the way.

Jamatter was too strong for Keyes and he slammed the British officer against a door, waking up Leutzen, Kaufholz, Bartl and Kovacic. The four men jumped from their beds and grabbed their weapons. Realizing the operation had already gone awry, Campbell closed on the courageous Jamatter and shot the German with his .38 revolver. The element of surprise was gone and the three raiders knew time was now of the essence. ‘We found ourselves, when we had time to look round, in a large hall with a stone floor, it had a stone stairway leading to the upper stories on the right,’ said Campbell.

We heard a man in heavy boots clattering down the stairs though we could not see him nor he us, as he was hidden by a right hand turn in the stairway. He was shouting ‘What goes on there?’ As he came to the turn and his feet came in sight, Sergeant Terry fired a burst with his tommy-gun. The man turned and fled away upstairs.

According to the subsequent German report just as Terry fired his burst at the man on the stairway, Leutzen emerged from the workroom on the ground floor and was confronted by Campbell and his .38 Smith & Wesson. ‘Leutzen jumped to one side and tried to take cover,’ ran the report. ‘Lieut. Kaufholz, who by now had stepped up next to Leutzen, returned the fire, but fell to the ground having been hit himself several times. Two of the intruders chose this moment to enter the room and throw two hand grenades’.

In his version of events, Campbell recalled that Keyes flung open a couple of doors on either side of the hall, but the room beyond each of these was empty. Then, seeing a crack of light under one door, he opened it and ‘fired two or three rounds with his Colt .45 automatic’. It was Campbell’s suggestion to throw in a grenade (one, and not the two mentioned in the German account) so while Keyes held the door shut, the captain removed the pin from a grenade. ‘I said “Right” and Keyes opened the door,’ said Campbell. ‘I threw in the grenade, which I saw roll to the middle of the room, and Sergeant Terry gave a burst with his Tommy-gun’.

Jamatter was probably armed with the German armed forces’ standard-issue rifle bayonet, the Seitengewehr (Sidearm) 94/98. This weapon had a 9.9in blade that was 1in wide at the hilt. (© Royal Armouries PR.10224)

As Campbell threw the grenade into the room Keyes yelled ‘well done’. The next instant there was a burst of machine-gun fire. ‘A bullet struck him just over the heart and he fell unconscious at the feet of myself and Terry,’ said Campbell.

After the grenade went off, this was followed by complete silence, and we could see that the light in the room had gone out. I decided Keyes had to be moved, in case there was further fighting in the building (and because we intended to blow it up), so between us Sergeant Terry and I carried him outside and laid him on the grass verge to the left of the front door. He must have died as we were carrying him outside, for when I felt his heart it had ceased to beat.

Paul Karl Schmidt, an SS officer who worked as Joachim von Ribbentrop’s press spokesman as well as for Joseph Goebbels’ press department, spoke to some of the Germans present on the night of the raid and wrote that the grenade knocked Leutzen over, but the German was unhurt. Kovacic, who was on his way to the door, received the full impact of the blast and lay dead on the tiles. A third NCO, Bartl, who was about to jump out of bed, was able to fall back and remained unscathed. Presumably it was Bartl’s return fire that mortally wounded Keyes.

The commotion on the ground floor had brought Weiss, Schulz and Ampt running from their conference on the first floor. Having instructed his orderly to hide all-important documents, Weiss and his fellow officers armed themselves with pistols and crept along the landing in darkness towards the top of the stairs. When Ampt first shone his torch down the staircase, its beam picked out Keyes, lying motionless on the floor. He switched off the torch and told Weiss what he had seen. A minute later, when Ampt illuminated the ground floor once more, the body had been removed. ‘Everything was quiet,’ ran the German report.

The door of the house had been closed again. Groans were to be heard coming from the workroom… On entering the room the two officers [Ampt and Schulz] found that the floor was covered with water, which was flowing from the central heating apparatus, damaged by the explosion of the hand grenades [sic]. The water was mixed with blood. Lieut. Kaufholz was lying on the ground with severe gunshot wounds, and Rifleman Kovacic was lying on his bed. They both appeared to be severely wounded.

Taken in 2012, this photograph shows the hallway of the villa where Keyes was shot. The main entrance to the villa is to the left, and Keyes would have grappled with Jamatter before, in all probability, being shot accidentally by Capt Robin Campbell. (Photograph courtesy Steve Hamilton – Western Desert Battlefield Tours)

At the back of the villa, seen here, Denis Coulthread and Charles Bruce were unable to force their way inside. Instead, they stood guard and, along with Drori, the interpreter, shot dead Jäger in his pyjamas. (Photo courtesy Steve Hamilton – Western Desert Battlefield Tours)

After Robin Campbell banged on the door of the villa and demanded entry, a military policeman called Jamatter, armed only with a bayonet, opened the door. He was pounced on by Keyes, smaller but carrying a Colt pistol. The pair grappled in the hallway and Jamatter cleverly used Keyes to shield himself from Campbell. Meanwhile, Terry fired a burst from his submachine gun up the flight of steps leading to the first floor. The commotion alerted three other Germans billeted on the ground floor and, sensing that they were in danger of losing the initiative, Campbell opened fire with his .38 revolver. According to the contemporary British version of events, with Jamatter disabled the raiders proceeded to hurl grenades into the rooms on the ground floor. It was then that Keyes was mortally wounded by a burst of fire from inside one of the rooms. However, in recent years there has been speculation that Campbell accidentally shot and killed Keyes during the struggle with Jamatter, a theory that Terry didn’t deny shortly before his death in 2006.

Meanwhile, at the back of the villa, Denis Coulthread and Charles Bruce were standing guard by the back door, behind which was a small office that had formerly served as a kitchen. It was crammed full of files and office tables; at the back of the room was a spiral staircase into the cellar, which served as the sleeping quarters for Alfons Hirsch and another NCO. In fact, the back door had no lock, so the pair improvised each night by pushing a barrel of water up against the door.

Coulthread spotted the yellow disc of a torch dancing through the darkness. The torch was held by an Oberleutnant Jäger, whose own workroom was separated by a partition of three-ply wood from the one destroyed by the Commandos. On hearing the gunfire Jäger had jumped out of the window in his pyjamas, taking his torch and his sidearm with him.

Coulthread wasn’t alone in spotting the danger. Drori, the interpreter, also saw the beam of the torch through the driving rain and pressed himself against the wall of the villa, his rifle at the ready. When Jäger was 10 yards away, Drori stepped out of the shadows and fired. ‘I just stood there and he very obligingly walked onto the end of my gun. All I had to do was pull the trigger,’ Drori told Coulthread. ‘The German did not shout or sigh, but fell down silently’.

A few moments later Campbell and Terry emerged from the building, carrying Keyes. Drori asked if he could be of any assistance. ‘No,’ replied Campbell. ‘He’s dead.’

Drori then gestured to the German he had just shot dead and Campbell congratulated the interpreter on his kill. ‘Are we going to retreat, sir?’ Drori asked Campbell.

‘No,’ said the captain.

According to Drori’s account he was ordered to remain with the body of Keyes by Campbell, who returned to the front entrance of the villa with Jack Terry. Suddenly, there was a burst of gunfire, followed by a groan and an urgent shout from Terry. Drori dashed round the side of the villa and discovered that Campbell had been shot in the shinbone by one of his own men, who had mistaken him for a German.

While Terry administered morphine to treat Campbell’s badly shattered leg, the captain ordered Kearney and Coulthread to blow up what they could with their sticks of gelignite. These explosives were taped together and at one end was a fuse with a large brimstone head. Kearney lit the fuse and threw the gelignite through the window left open by Jäger. Another Commando, Spike Hughes, lobbed an incendiary bomb into the room, but neither device detonated.

An example of the explosive time pencil – officially the ‘Switch, time delay, No 10 “Pencil”’. (© Imperal War Museum MUN 1967)

A member of the LRDG driving a jeep in 1942. Cooke’s party initially headed east towards the Italian headquarters at Cirene in the expectation of rendezvousing with an LRDG patrol. ‘Unfortunately, with the weather and the late hour, we were unable to get the lift we expected on the road,’ said Cooke. (IWM CBM 1212)

Meanwhile, Coulthread and Charlie Bruce had turned their attention to the electric light plant; they could hear the hum of a generator behind a large steel door. Unfortunately, the rain had dampened their fuses and the matches they carried inside their battledress, so Terry suggested they stuff the explosives into an external pipe, followed by a hand grenade. This plan worked, the light plant exploding with a muffled roar.

Terry told Bruce to take some of their explosive time pencils and plant them among the vehicles in the car park. This device was a slim, 6in-long glass tube with a spring-loaded striker held in place by a strip of copper wire. At the top was a glass phial containing acid, which broke when gently squeezed. The acid then ate through the wire and released the striker. The thicker the wire, the longer the delay before the striker was triggered, and the pencils were colour-coded according to the length of fuse.

While Bruce set off towards the car park, Terry blew his whistle, the signal for the Commandos to begin their withdrawal. The morphine had dulled the pain from Campbell’s broken leg but the captain knew he was in no fit state to march the 18 miles back to the rendezvous; nor could he expect his men to carry him with the enemy on their trail. Campbell therefore handed command of the raiding party to Terry. After saying a hurried farewell to Campbell, the raiders ‘left him propped against a tree at the back of the house, and he gave them a map and all his remaining ammunition and explosives’.

Terry had been unable to find Bruce since he had set off towards the car park, and Charles Lock, Bob Murray and Jimmy Bogle also failed to appear at the sound of the whistle. Unable to wait any longer, Terry led the remaining 11 raiders north, stumbling through the dark for more than a mile until Terry disappeared over the edge of a gulley. Fortunately for the sergeant, a bush saved him from a nasty fall, but he lost his Thompson in the incident; it was decided that the party would lie up for the rest of the night rather than risking any further mishap.

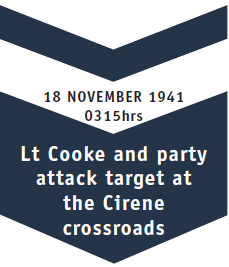

After leaving Keyes, Cooke and his five men, among them two soldiers called Gornall and Paxton, watched the main road until they heard the first sounds of gunfire from the villa. The raiders began marching as quickly as possible along the road. A large house with a garage offered the possibility of acquiring transport, but it was found to be impossible to break into the garage without giving away their presence so they continued on foot. Knowing that they had to blow up the pylon (approximately 8 miles from Beda Littoria) before sunrise, Cooke decided to stop the first vehicle that came along the road.

For nearly an hour no vehicle appeared, but then eventually they heard an engine in the distance. Gornall stood in the road and flagged the vehicle to stop, but the two Italian soldiers inside had heard over the radio of the attack at Beda Littoria. Momentarily slowing down as it approached Gornall, the lorry then accelerated and the Commando was forced to jump for his life. Cooke and the rest of the men opened fire, resulting in the vehicle swerving off the road 15 yards away. Despite desperate attempts to start the lorry, the Commandos found it impossible and so, after binding the two terrified Italians, the raiders continued down the road. The blistering pace set by Cooke took its toll on the men. ‘We had to drop off two of the boys as they couldn’t make it. One of them had lost his shoes and his feet were in a fearful state,’ he said. ‘However, we filled them up with grenades, etc. and told them to muck up any odd transport, or what have you, that they could find, and try to get back’.

At 0300hrs Cooke and his remaining three men reached the communications pylon, but were then confronted by the same problem experienced a couple of hours earlier by their comrades outside the villa. ‘All matches, etc. for setting off the charges were soaked, even inside the oilskin pouches,’ said Cooke. ‘I tried a grenade under the charge and then running like hell and falling flat and felt very foolish when it turned out a blind. The second one went off, but the charge didn’t. I returned to the boys nearly frantic with wind up and frustration and nerves, cursing pretty profusely’.

It was Gornall who provided Cooke with the solution to his problem: ‘I suppose a self-igniting incendiary wouldn’t be any good sir, would it?’ he said. Cooke congratulated the soldier on his initiative and a minute later the pylon went up in flames. After admiring their handiwork for no more than a second or two, Cooke and his men vanished into the darkness.

Within minutes of the Commandos’ flight from the villa, dozens of Italian soldiers appeared from the barracks behind the town hall. ‘Orders were given for a systematic search of the garden,’ ran the German report on the raid. As well as discovering the bodies of Boxhammer, the young guard, and Jäger, the Germans also came across the wounded Campbell propped against a tree, ‘and stood over him debating whether to finish him off’. Common sense prevailed, however, and the wounded man was brought inside for questioning. ‘An attempted interrogation of the English officer, whilst still suffering from the shock of his wound, was unsuccessful, as it was impossible to get him to make a statement,’ the report stated. Instead a different approach was tried, as described by Paul Karl Schmidt:

Captain Campbell had received a shot from a tommy-gun or a revolver at close quarters which had completely smashed his shinbone in the centre… By rights the leg should have been amputated, since the prospect of healing was very small and the danger of infection very great. At his request, Doctor Werner Junge did not amputate and tried to save the leg. Since Junge spoke fluent English he was given orders to question Campbell. The latter did not betray the fact that he knew German. Junge could discover nothing of any importance. On the contrary, Campbell saw at once through the Doctor’s game and said at last in German: ‘You needn’t bother – you won’t get anything out of me.’ (Carell 1961: 56)

With Campbell refusing to talk, the Germans had to make their own assumptions about the raiders, few of which were correct. ‘Judging by their clothing, one comes to the conclusion that the Englishmen had been dropped from the air and belonged to an Airborne Unit,’ Weitz said in his report. ‘Both [Campbell and Keyes] had not shaved for several days and one could conclude that they had been dropped some time ago, and had chosen this day of particularly heavy rain as favourable for their undertaking’.

Just as the Germans had finished conducting their search of the garden and surrounding areas, word reached them of the sabotaged communications pylon and damaged truck on the road to Cirene. Weitz dispatched a patrol to ascertain what had happened and they discovered ‘footprints on the ground [that] gave the impression that they were made by English rubber soled shoes’. At first light the manhunt began, the local Italian Carabinieri enlisting the help of locals by promising ‘eighty pounds of corn and twenty pounds of sugar for each Britisher that you betray to us’. Among the excited throng of Arabs in Beda Littoria was Awad Mohammed Gibril, one of the two guides who had been told to wait by the cedar tree. When none of the Commandos appeared he had crept into the village to discover what had unfolded. Now, in the early-morning rain, the market was full of ‘German and Italian soldiers with armed police spread out like locusts going northwards’. Awad asked one of the market traders what all the fuss was about, and ‘was told that the British had attacked Rommel’s House but unfortunately Rommel was not there. The Arabs were laughing and were delighted with the exploit’.

The view from the conning tower of a T-class submarine, similar to that of HMS Torbay and Talisman. The stormy seas at Chescem el-Kelb meant that the Commandos had extreme difficulty launching their dinghies. (Cody Images)

Cooke and his men, having opened fire on the lorry, headed north-west, towards the ancient Greek tombs at the foot of the second escarpment. ‘We lay up in an old tomb that day [18 November], very cold and wet we were,’ he recalled:

Pushed off next night to try and get back to the ship. We went very hard and got back to within five miles of the place, but at about 8.30 that morning had to rest, which we did in a cave with some Arabs. We didn’t know it, but we had sat down in front of two battalions that were beating the scrub for us and looking in all the caves. The Arabs managed to slip out before we got the troops right on top of us, and tried to divert attention from the cave, by a little shooting on their own account, but no go. Two blokes came down into the cave and we shot them, then they threw down so much stuff at us that the fumes nearly suffocated us, so we called it a day.

Awad the guide, meanwhile, having seen the confusion in the market and the start of the German manhunt, quickly made his way back up the cart-track to the cave where Bob Fowler had been left to guard the stores. Fowler had already guessed something had gone badly wrong because he’d seen no sight of his comrades since they had left 12 hours earlier. Keyes’ camera, which had several incriminating photos of the raiders, was buried deep in the mud along with a pair of field-glasses. Not long after Fowler had accomplished this task he was collected by Awad and together they set off to the beach.

A short distance behind Fowler and Awad was Charlie Bruce who, having laid his time pencils among the vehicles in the car park, had made his way away from Beda Littoria accompanied by Charles Lock, Bob Murray and Jimmy Bogle. The four Commandos reached the cave not long after Fowler had set out and on finding it empty, continued north. Headed in the same direction was the 12-strong party led by Terry, all of whom were by now tired, cold, wet and hungry. They were also aware that scores of enemy soldiers would now be swarming after them. It was a sobering thought as they made their weary way across the Jebel el-Akhdar.

Following the landings on 15 November, Lt-Cdr Miers, skipper of the submarine Torbay, had ordered Talisman back to Alexandria. So few raiders had got ashore that he would be able to transport them all back in his vessel, he told Talisman’s skipper, Michael Willmott. For the next two days Torbay remained off the beach at Chescem el-Kelb, lying on the bottom of the sea during the day and surfacing at night. On 17 November Miers had received a weather report ‘which unfortunately did not even approximate to the prevailing weather conditions, which were most unfavourable’ (PRO 2001: 289).

On the morning of the 18th, as the Commandos raced south from the villa, Miers surfaced and once again looked out from the conning tower on a storm-ravaged landscape, the sea lumpen with a swell running from the north. Suddenly an enemy aircraft was spotted in the distance (probably searching for the Commandos) and Torbay was forced to dive to the bottom, where it remained until 1900hrs.

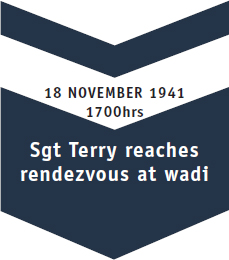

At 1700hrs, two hours before Torbay surfaced, Terry and his 11 men had reached the rendezvous point in the wadi containing Laycock and his small party, who passed the time reading and doing crossword puzzles. Terry gave a potted account of the raid, describing the death of Keyes and the wound to Campbell, and also mentioned an encounter with a group of Italian native levies a few miles back. It was Drori’s opinion that these men weren’t to be trusted and had probably reported the Commandos’ presence to Italian soldiers.

While Terry and the Commandos tucked into a meal of biscuits and bully beef, Laycock made his way to the beach to see if he could spot Torbay. First, however, he went to the cave where they had left the rubber dinghies and Mae Wests three days earlier. They were gone. As Laycock made his way along the beach he saw an Arab watching from a distance. The man wasn’t Senussi and when Laycock approached him, he took off. Unsettled by the loss of the dinghies and the stranger on the beach, Laycock sent word to the men in the wadi to move to the beach, leaving three men behind to wait for Cooke’s party to arrive.

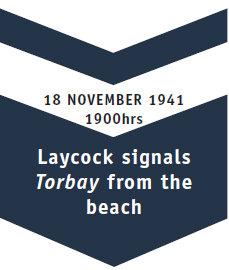

By now Bruce and his party of Commandos had also reached the wadi and the Commandos took up positions in some of the caves close to the beach. Counting the three men left in the wadi, Laycock had 21 men under his command, including two Arab guides. At 1900hrs Laycock spotted Torbay a quarter of a mile out to sea through his field glasses. Using his signal torch the colonel asked for some Mae Wests and a grass (towing) line to be delivered to the beach. From the conning tower of the submarine, Miers was troubled by the signal, although as agreed with Laycock he didn’t respond to the signal with one of his own because of security precautions. He was at a loss to understand why the beach party should require life jackets when each Commando had landed wearing two Mae Wests.

Nevertheless, Miers obeyed the signal, instructing Lt Ingles and Cpl Severn of the SBS to prepare to paddle ashore in a folboat containing life jackets, food and a grass line. In addition:

they also were to inform those on shore that the weather was unsuitable for boat work but was improving, and that in order not to delay re-embarkation, if a large proportion of the force was present, the Torbay would close at dawn to within 100 yards of the spit of sand at the western end of the beach, so that they could swim out to her. (PRO 2001: 290)

As Ingles and Severn prepared for their mission a second signal was received from the shore, informing Miers that the enemy was nowhere near the beach. The swell was by now so heavy that it proved impossible to launch the folboat, so at 2250hrs the two SBS men attempted to leave the casing of the submarine in a rubber dinghy. This, too, was not possible because of the heavy seas, but Miers decided to lash the 23 life jackets, 12 water bottles and quantity of food securely inside the dinghy and launch her unmanned, confident that the swell would take her to the beach.

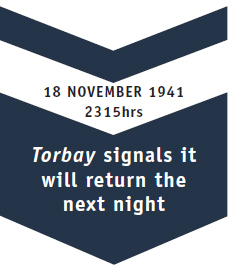

At 2315hrs Miers used a shaded Aldis lamp to signal to Laycock of his intentions, also asking what had happened to the dinghies and for news of the outcome of the raid. In fact, by this time the dinghies had been found in another cave, so Laycock apprised Torbay of the fact – although his signal was not understood by Miers. All Miers comprehended was the answer to his question about the raid: ‘Goodness only knows,’ replied Laycock. ‘Some killed in camp and missing from H.Q.’ (quoted in PRO 2001: 290).

It was not an encouraging response, and Miers signalled that he could close the beach immediately and have the men evacuated from the beach. Laycock, convinced that the raiders were in no fit state to brave the waves, replied that they would try again the following night. Miers would have preferred to evacuate the men that night, but he had no choice but to accept Laycock’s decision, so Torbay stood out to sea for the rest of the night. Back on the beach the Commandos dispersed in small groups into the caves, where they slept through the hours of darkness while guards patrolled both ends of the beach.

Laycock was awake an hour before dawn on 19 November and, with Pryor’s assistance, he drew up a defensive perimeter for the beach. Three sentries would be posted at the best vantage points looking inland, while their flanks would also be guarded. The rest of the men would remain in the caves until the submarine returned that night. It was also decided that once Laycock’s party had finished breakfast, Pryor would organize a relief of the three men who had spent the night at the wadi waiting for the return of Cooke and his party.

By the time the raiders had eaten a meagre breakfast, dawn had broken and Pryor could see from his cave an old man ploughing a field with a donkey and a camel half a mile to the west of the beach. A couple of hours later, as Pryor continued to watch the ill-matched ploughing team in amusement, a shot rang out from the sentry posted on the western end of the beach. ‘We ran in a fusillade of pops to action stations in a ruined house on a knoll back of our cave,’ recounted Pryor.

I saw our chaps from the cave across the stream running out and taking position likewise, facing west, and there in the distance were some Arabs in red turbans crawling towards us. Everybody fired and they fired back, there were a few bigger bangs that I imagined were from a mortar, and I remember thinking ‘our old wall doesn’t look a bit bullet proof’. There didn’t appear to be many of these native troops as enemy, so we discussed, and thought if we could mop them up, we might still get away in the Torbay that night.

The wadi to the west of the beach at Chescem el-Kelb up which Lt John Pryor and Cpl John Brittlebank advanced in attempt to prevent being encircled by the enemy on the morning of 19 November. In the event Pryor was shot and wounded, and later captured, while Brittlebank was one of the three raiders to escape. (Photograph courtesy Steve Hamilton – Western Desert Battlefield Tours)

Armed with his service revolver and taking the reliable Cpl Brittlebank, Pryor set off with the aim of getting round the seaward side of the enemy. The pair heard the crack of bullets close by as they sprinted across the beach and into the dead ground of a wadi. Temporarily concealed from the enemy, Pryor and Brittlebank advanced up the wadi towards a stone drinking-trough. Suddenly they came under fire. They ducked, and agreed that the enemy were poor shots. Cautiously, the two men advanced up the wadi, using the rocks as cover and relying on the continued inaccuracy of the half-a-dozen Arab soldiers they could see inland. ‘Behind the next rock we stopped again in our approach,’ recalled Pryor, now within 200 yards of the enemy. ‘I looked round and saw that my man [Brittlebank] had managed to get his tommy gun jammed solid. I poked it about a bit and banged it, but couldn’t budge it. Rather cross I said “Well try and clear it for God’s sake – I’m going on”’.

Pryor went on alone, crouching and running a further 50 yards up the wadi towards a cluster of rocks. Once behind the cover of the rocks, Pryor scanned the terrain and saw more Arab soldiers working their way down the scrubland towards the wadi. With just his revolver and one grenade, Pryor decided to withdraw back to the beach and tell Laycock what he had seen. A bullet struck a rock just as Pryor dashed out from behind his protection. Then, in the next moment ‘something like a horse kicking me up behind bowled me over’. Realizing he’d been hit in the thigh, Pryor crawled down the wadi to a flat stone, which he held up like a shield. ‘They chipped that twice, and thinks I “if they move a bit they can get me. I must get out,” and found my leg would carry me well – which it did back to Bob [Laycock]’.

According to Pryor, when he eventually reached the cave, Laycock’s reaction on hearing of the enemy’s strength was to curse ‘Damn it, that’s no good.’ In Laycock’s account of their discovery, however, he remained unruffled by the presence of ‘Carabinieri Arabs known to be stationed at [El] Hania’, approximately 8 miles to the west. ‘This did not worry us unduly since we were confident that we should be able to drive them off until darkness allowed us to retire to the beach for evacuation, which now seemed feasible as wind and sea were rapidly abating,’ wrote Laycock. However, it was soon reported that Germans were now coming down the same wadi up which Pryor and Brittlebank had advanced a couple of hours earlier. In addition, the lookouts reported that a large force of Italians was approaching from the north, presumably having overrun the three men left in the wadi a mile inland. ‘Fairly accurate fire was brought to bear on us, but we were behind good cover and suffered no casualties,’ said Laycock.

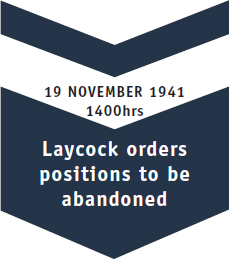

Although the enemy were not equipped with automatic weapons, they were maintaining a steady advance, and bringing a considerable volume of rifle-fire to bear on and around our position. It was now evident that it would be impossible to hold the beach until dark against such superior forces, and that our only remaining line of retreat would soon be cut off. At about 1400 hours I therefore reluctantly decided to abandon the position and to adopt the alternative plan of hiding in the Jebel until we could rejoin our advancing main forces (the 8th Army). Nothing could be seen of our Western detachment whose original position was now occupied by the enemy and, as a runner sent to reconnoitre, returned with negative information, I presumed that they had been killed or driven off Westwards. I ordered the main body to split into parties of not more than three men each, to make a dash across the open, and to retire through our Eastern detachment to whom they were to pass on my orders.

Once in the Jebel, the men were told by Laycock to ‘adopt’ one of three plans: (1) at nightfall return to the beach and swim out to Torbay; (2) to make their way to the area of Slonta in which vicinity the Arabs were known to be friendly and where there was a chance of being picked up by the LRDG; (3) to remain hidden in the Jebel until the area was overrun by Allied forces.

Leaving Pryor in the hands of an apprehensive medical orderly called Edward Atkins, Laycock disappeared into the scrub and made his way towards the eastern flank, where he found Terry waiting. Together they struck out for the Jebel. ‘The first half mile of the withdrawal was unpleasant owing to the open nature of the country, but the enemy’s marksmanship seems to have been particularly poor, and although we had some close shaves, I do not think we suffered a single casualty since Sergeant Terry and myself would almost certainly have observed any which had occurred,’ said Laycock.

Back at the cave the wounded Pryor and Atkins, the medical orderly, waited for the enemy to close, aware that the Arab troops in the pay of the Italians had a reputation for cruelty. Atkins asked Pryor if he thought they would be shot. ‘Yes,’ replied Pryor, who remembered the medic’s ‘face was a picture’ as he absorbed the gloomy prediction. In fact the two men were well treated by their captors, with Pryor transported to the Italians’ HQ on the back of a mule.

Shortly after dawn the Commandos’ position came under attack from a detachment of Libyan troops under Italian command. The enemy, although not carrying automatic weapons, were superior in number to the cornered British and began to work their way towards the caves where they were sheltering. Pryor and Brittlebank attempted to get round the seaward side of the Italians, but in the course of doing so Pryor would be shot in the thigh by a rifle bullet. Here we see the Libyan soldiers advancing on the beleaguered Pryor and Brittlebank, moments before Pryor received his wound.

Vice Admiral H. D. Pridham-Wippell, second-in-command of the Mediterranean Fleet, with Lt-Cdr Miers (right) on the deck of HMS Torbay at Alexandria Harbour, 10 May 1942. Miers was awarded the Victoria Cross in March 1942 after a daring action that saw the destruction of two enemy vessels. After the war Miers rose to the rank of rear admiral and was knighted, but following his death in 1985 allegations surfaced linking him to attacks on shipwrecked enemy personnel. (IWM A 10274)

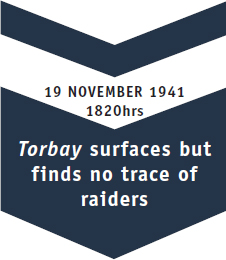

While the Commandos had been fighting a losing battle, Torbay had remained submerged, making a reconnaissance of the beaches through the periscope but seeing nothing of the fighting raging in the wadis out of sight from the sea. At 1820hrs on 19 November, Torbay surfaced, but could see no sign of the Commandos on the beach. By now the weather had eased, and a long swell was running from the north-west straight onto the beach, so Miers instructed Lt Tommy Langton and Sgt Cyril Feebery to go ashore in a folboat. Despite the calmer seas it was still extremely difficult to launch the kayak, but eventually the pair were paddling inshore. ‘We rode into the beach on the crest of a wave like a couple of mermaids,’ recalled Langton who, like his No. 2, weighed 14 stone.

The beach was deserted, and after emptying the boat we walked off along the beach toward a light which had appeared on the hillside. This light was the correct colour [blue], but not giving the correct signals, so I was most suspicious of it. After going a little way I thought I saw a movement inland, so we crept towards it but saw nothing further. However, we both heard a shout soon afterwards and since we were by then some distance from our boat and liable to be cut off, I decided to return to it and wait. (Quoted in Pitt 1983: 18)

Something wasn’t right – both men sensed it – but neither wanted to return to the submarine without first ensuring they weren’t leaving their comrades in the lurch. Langton and Feebery agreed to paddle parallel to the shore towards the blue light. Once abreast of the light, Langton flashed his own white torch and thought he heard a shout in response. Suddenly, a roller crashed into their folboat, capsizing the kayak and causing Langton to lose his Tommy gun in the surf. Even worse, a paddle was lost. ‘We crawled along the edge of the surf for a while on hands and knees hunting for the paddle,’ said Feebery. ‘I had the nasty feeling all the time that someone up there in the trees was staring at my back through the sights of a rifle’ (Feebery 2008: 44). Finally admitting defeat in their hunt for the missing paddle, the pair climbed back inside the folboat – which had now sprung a leak – and, relying on the immense strength of Feebery (a former boxing champion), returned to Torbay.

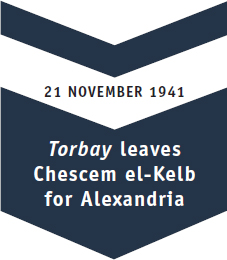

Miers spent the rest of the night patrolling the bay at a safe distance, but no further signs were seen from inland. Then, at dawn on 20 November, ‘it was seen that all the beaches were in the enemy’s hands and they were evidently carrying out a search in which they were being helped by aircraft’ (quoted in PRO 2001: 290). Torbay remained submerged until the evening, hoping against hope that the enemy had made an unsuccessful sweep of the beach for the Commandos. But the storm had now dissipated, leaving Miers increasingly uneasy ‘as the weather … was ideal for E-boat operations’ (quoted in PRO 2001: 290) and therefore they risked detection by the Germans. Resolutely remaining off the beach until daylight on 21 November, Miers finally sailed from Chescem el-Kelb at midday, arriving in Alexandria three days later.

By then all but three members of the raiding party had been caught by the Axis forces. John Brittlebank, having lost his officer, Pryor, struck out alone and succeeded in reaching Allied lines 40 days later, on 28 December. (Pryor for a number of years believed that Brittlebank had been killed on the beach.) Three days before Brittlebank reached safety, Laycock and Terry had also made it to the British Eighth Army HQ at Cirene, now in Allied hands. ‘Our greatest problem was the lack of food and, though never desperate, we were forced to subsist for periods which never exceeded two and a half consecutive days on berries only, and we became appreciably weak from want of nourishment,’ recalled Laycock. ‘At other times we fed well on goat and Arab bread, but developed a marked craving for sugar. Water never presented a serious problem, as it rained practically continuously. Our failure to obtain reliable information of the advance of the British forces we found aggravating in the extreme’.

Nevertheless, the pair had made it, a remarkable feat of endurance and initiative that was lauded in the British press. So was the raid itself, immortalized as a glorious example of British pluck, conveniently overlooking the brutal reality that the operation had achieved little other than the death or capture of many brave and well-trained men.