3

The Perfect Pathological Storm

The potato fueled the rise of the West.

—Charles C. Mann, 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created

A perfect storm results when the confluence of several phenomena turns a bad situation, sometimes a literal storm, into something far worse. The potato famine resulted from a perfect storm of poor choices in addition to poor communication and major gaps in our scientific understanding of pathogens. Historians, working with biologists, finally have a sense of which phenomena made the late blight so awful during the potato famine. Few of us, however, have listened to the historians. As a result, rather than grow our crops in ways that make disasters like the potato famine less likely, we have done everything necessary to make such catastrophes more likely. A perfect pathological storm gathers steam just over the horizon, and rather than threatening only a few boats, it threatens whole countries.

Many famines had occurred before the 1840s, but never one like the potato famine, never a famine of such great consequence tied so directly to a single pathogen and a single crop. The human toll was so great, in part, because of the extreme dependence of the Irish on the potato. In this regard, many populations are as at risk today as the Irish were then. But why did the pathogen kill so many potatoes? Why were there none that seemed to survive? The answer is important because it bears on our modern agriculture; it speaks to the risk our crops—including our modern potato—face today, including a recurrence of late blight.

In addition, the answer depends on decisions made long before the Irish ever started to grow potatoes, decisions made during the travels of the Spanish conquistadors and their aftermath. We left it to guys like Francisco Pizarro to choose the crops we now farm. He and other conquistadors may seem both repugnant and far removed from your daily life. Nonetheless, they influence nearly every bite of food.

Francisco Pizarro was born in Trujillo, Spain, around 1475, the illegitimate son of an economically marginal family. Some say he was an ugly baby; certainly he would become an ugly man. He grew up desperate, illiterate, hungry, strong-bodied, and morally loose. When the opportunity arose to travel to the coast in search of work and adventure, he took it. Once there, Pizarro joined the military for several years. He traveled to Italy and fought bravely, terribly, or both, according to his biographers. Eventually he boarded a boat headed for the Americas, dreaming of the riches he had heard others talk about in the long hours he spent on ships. Leaving Spain behind, Pizarro crossed the sea. He and other conquistadors like him were perhaps not the people to whom Western society should have entrusted the task of choosing the varieties of crops that moved around the world. Nonetheless, that is just what happened.

Pizarro’s first trip from Spain to the Americas was part of an attempt to establish a new colony in what is now Colombia (with Alonso de Ojeda, who first traveled to the Americas on Columbus’s second expedition). The conquistadors and colonists who followed in their wake planted seeds from European plants. They let loose horses, cows, and pigs. They wanted to be kings—or leaders, anyway—of a new, tropical Europe. But the colony failed. Many of the colonists died. Houses faded back into jungle soil, and the cows, pigs, and horses ran loose and multiplied. So, too, did some of the crops. Thanks to this effort and others like it, Pizarro and his fellow conquistadors spread crops and domesticated animals in the Americas.

But this was just one half of the great exchange; the other half involved the crops that would come back to Europe. But first those crops had to be found. In 1513, Pizarro and the explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa headed west across the South American continent, searching for a way through to the Pacific. Improbably, they found one. Pizarro went on another expedition in 1523, again across Panama. Many died, and nothing was discovered. Nine years later, in 1532, Pizarro tried again, this time with his friend Diego de Almagro. They made it to the Pacific and again pressed on, following the still-unmapped coast. No one knew for sure what lay ahead, but there were stories. Men spoke of a great empire to the south, an empire of gold and riches. To arrive at the empire, one needed only follow the coast and then ascend the mountains. The coast would prove treacherous, and “the mountains [the Andes] were higher, the nights colder, the days hotter, the valleys deeper, the deserts drier, the distances longer”1 than anywhere the conquistadors had been before.

What followed was the discovery of the Inca Empire, the death of the Inca ruler Atahualpa, the marriage of Francisco Pizarro to Atahualpa’s sister, the birth of their daughter Francisca Pizarro (who would go on to lead an interesting life in Spain and to marry Pizarro’s brother), the death of Francisco Pizarro at the hands of men loyal to the son of Pizarro’s friend Almagro (Almagro himself was by then already dead; Pizarro killed him), and the removal to Spain of a great deal of Inca gold and even more silver. Also—and this is a big “also,” perhaps the very biggest “also” of modern, Western, civilization—amid all this, the conquistadors moved crops from one place to another. As they did, the future of agriculture and humanity changed.

But which species would the conquistadors carry back to Europe from the temperate parts of the Americas? And to Africa and Asia from the tropical reaches? There were no easy answers. The decisions these men made about what to bring back from their travels affected the choice of crops from the Americas that we eat today; their choices lurk in the varieties of crops you find in the store, varieties that, as often as not, are the ones they picked. The conquistadors chose from among the plenty, but without regard for the centuries to come. In an ideal world, conquistadors such as Pizarro would have brought back many varieties of each species of the new crops they were encountering. These would have included varieties that differed in taste, in the climates and soils in which they might grow, and, as important as anything, in their resistance to pathogens. Of course what happened was the opposite. Consider, for example, the root crops of the Andes. At the time Pizarro arrived in the Andes the Inca farmed no fewer than ten thousand varieties of a dozen species of root crops. Pizarro and his men would have eaten many of these, cooked for them by their Native American wives. Of these multitudes a small subset was gathered by the Europeans. Perhaps one in ten thousand of these varieties made its way back to Europe. This raises two questions. First, why were so few varieties and crops brought back to Europe? Second, how were the varieties that made it back chosen? It is the answer to the latter question that was to shape the fate of the potato.

As to why so few varieties were brought back to Europe, the first problem was the conquistadors themselves. The conquistadors were not, for the most part, farmers. Nor were they skilled, necessarily, in learning from the locals. They were not even that good at distinguishing food from nonfood, much less the subtle differences among the former.2 In addition, some species and varieties they did not see. No record seems to exist, for example, of encounters between conquistadors and the root crop oca (as a result, you might not have heard of oca). Other species they encountered but failed to note as food. Others still were recorded as food but viewed as unappetizing. Native Americans consumed frogs, beetles, termite queens, moths, bees, spiders, locusts, worms, mice, ticks, and algae. But because the conquistadors thought these items too strange to bring home, they, for the most part, never made it to our modern plates.3 Ecologists talk about ecological filters, those features of habitats or of particular moments in evolutionary history that allow some species to move and thrive and prohibit others from doing so. The first crop filters all related to choices made by the conquistadors.

The conquistadors’ preferences had lasting impact. If a food from the Americas was not tasty to the conquistadors, you are very unlikely to have ever seen it in a major store.

But even once the conquistadors decided to gather a particular plant or animal, whether it made it back across the ocean—or even to the coast—was another story, one in which ecology’s laws were once again at play. The journey was long and terrible, especially for a delicate seed. When the men with whom Pizarro conquered the Inca Empire returned from the Andes, the route had many steps. First they had to descend the Andes to Arica, on the Chilean coast. In Arica they would board their boats and travel north to the Pacific coast of Colombia or Panama, then cross back through the jungles of the Isthmus of Panama to the Caribbean coast (the Panama Canal, of course, did not yet exist). Any seed or fruit traveling with them would have been exposed to constant humidity and months of conditions under which the most likely outcome was rot. It would have had to travel for miles in a small satchel roped to a dirty sailor or in a bag that was left banging on the back of a slowly dying mule in a mule train. Just a small handful of plants, whether in the form of roots, tubers, or seeds, made it all the way to the coast.

And that was just the first step. Once a plant made it to the Caribbean coast it still had to make it back in the ship; it had to survive the nearly four months it would take to get to Spain. On the ships of the earliest conquistadors, space was tight. Waste, rot, food, seeds, and sailors coexisted side by side, or failed to. The hold stank of excrement and rotten food. For reasons it is hard to imagine, given that the men were surrounded by the sea, the sailors sometimes threw the bones and offal of animals they ate into the bottom of the ship rather than overboard.4 Rats often numbered, even on relatively small ships, in the thousands—a dozen rats per sailor, by one quite reasonable estimate. Shipwrecks from the time are riddled with gnaw marks made by the teeth of rodents. The conditions of the food on Columbus’s fourth voyage to the Americas, for example, are said to have been so poor in hygiene and rich with life—grains and meats writhing with larvae—that the men preferred to eat at night so as to not see their food, not see what moved in their bowls. One ship from the late 1500s recovered off the coast of Florida contained evidence of three kinds of grain weevils, cockroaches, and dermestid beetles, all riding with the sailors from Europe to the Americas. The trip home would have been worse. And those same rats and writhing insects would eat any seed or root they came across.

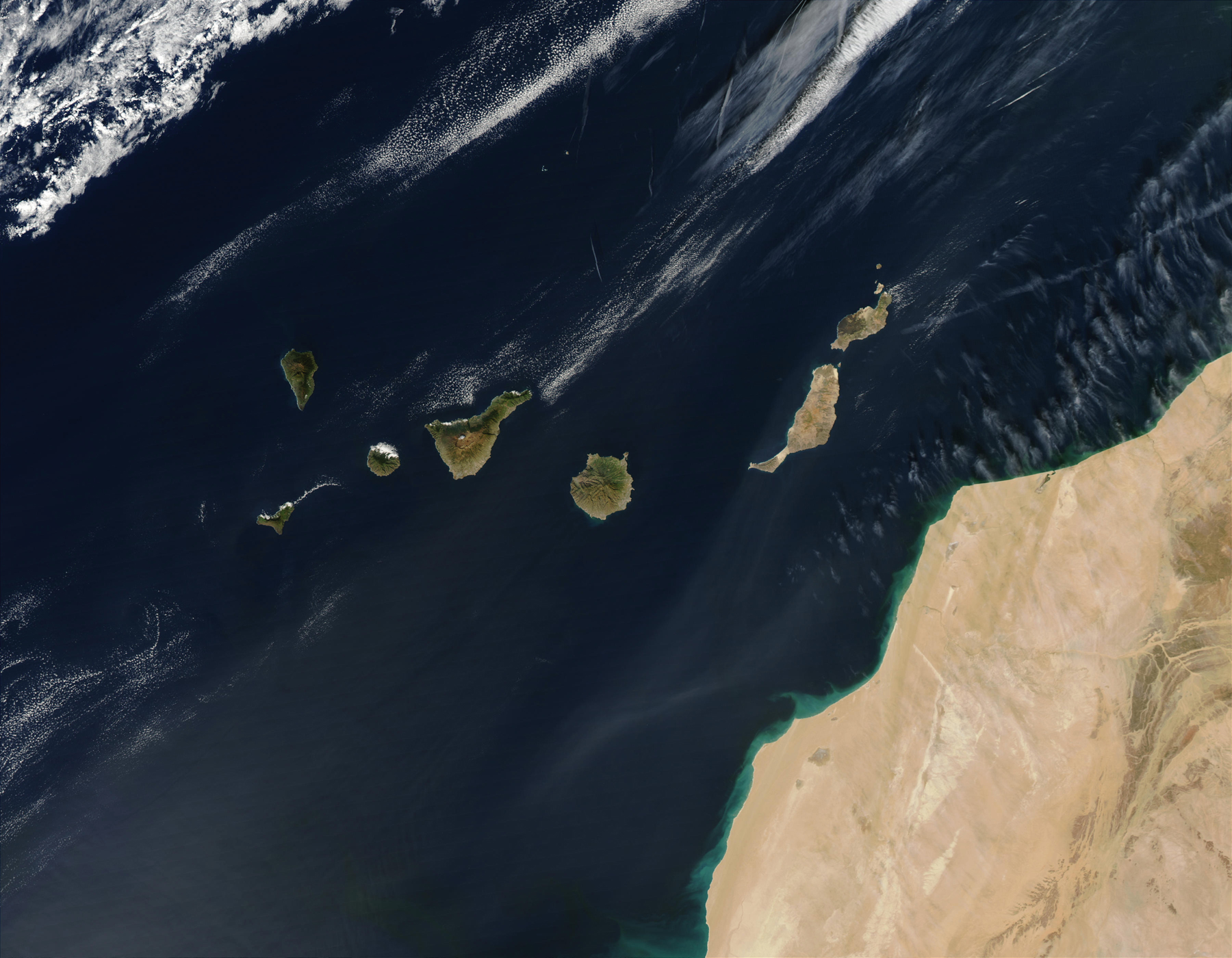

Figure 3. Satellite image of the Canary Islands and their location relative to Africa. These islands, isolated and unusual though they might be, have played an outsize role in the history of agriculture. Image by Jacques Descloitres, MODIS Rapid Response Team, NASA/GSFC.

The entire trip from the Andes back to Spain took, on average, two years.5 That any plant made it through these journeys alive is shocking. Those that made it did so because they were cared for and because they were the very hardiest and most indefatigable of the crops of the Americas. And even once a plant made it across the ocean, its journey into the European agricultural system was not complete. It still had to be able to grow somewhere in Europe. Nearly every trip to the Americas and back stopped in the Canary Islands (just as nearly every trip to Africa stopped in São Tomé and other islands off the coast of West Africa). The Canary Islands are volcanic subtropical islands. As a result, they include many of the key climates present in western Europe, including deserts, subtropical rain forests, temperate forests, grasslands, and even habitats that are snow-covered for part of the year. Crops could be established on the island as a kind of way station to further introduction. And whereas one had to travel among countries if one wanted to test out a potato in every potential climate in Europe, all one had to do in the biggest Canary Island, Tenerife, was travel from the coast to the top of the volcanic ridge. It is not surprising in this light that many crops that moved among continents did so via these islands—both from the Americas to Europe and from other parts of the world to the Canaries and then to the Americas. Banana and sugarcane (both native to the Far East), for example, spread to the Americas via the Canary Islands. Europeans then chose among crops of the Americas as they were coming from the Canary Islands. The Canary Islands became both a garden of possibilities and the place where all history associated with each crop was erased.6

The final step in filtering, intentionally or otherwise, the arriving crops into the subset we now eat was the process that occurred among European farmers and consumers. For sustenance crops, farmers nearly always chose the most fecund of the cultivars that arrived. This happened both because farmers preferred such varieties and because, once they began to grow them, the fecund varieties were those that a farmer was most likely to have in abundance. Each of these steps, these winnowings in the process of moving crops to Europe, could take whole human generations, but they rarely did.

Just thirty years after Pizarro raced up the hill to see the Inca Empire, just thirty years after he was bathed in silver, potatoes were being sold from the Canary Islands to mainland Spain.7 Considering all the steps involved, that is as fast as potatoes could possibly become a commercial crop in Europe. We don’t know how many varieties arrived initially, but we can surmise, based on the ecological filters through which they passed, that these varieties shared certain features. They were all able to survive on ships. They all arrived devoid of genetic diversity. The crops were also devoid (largely) of any partners they might have relied on in their native range. If their roots needed special fungi that helped them to access resources, for example, those were unlikely to have made the journey. If their flowers needed special pollinators, those, too, were left behind.8

The end result was that of the twenty-five root and tuber crops grown in South America, just the potato made it to the Canary Islands. Of the thousands of varieties of Andean potatoes (from nine separate subspecies), just a few dozen arrived in the Canary Islands, all of which appear to have been of the same subspecies (Solanum tuberosum ssp. tuberosum). Of the few dozen varieties of potatoes that made it to the Canary Islands, just a handful made it to continental Europe. Of that handful, just the lumper and a few others grew well in Ireland, where growing seasons are short and days during those seasons are long. Of the particular lumper lineages that were present in Ireland, those that were favored were either resistant to stress associated with transit, fecund, or able to grow where the season was short and the days long. The result was a crop that was fecund yet homogeneous, a crop that grew well but only in the absence of pests and pathogens. And there was something else, too.

The potato plants in Europe came ashore “naked,” that is, without any of the traditional knowledge farmers in the Andes had acquired regarding planting, growing, storing, and preparing them over the course of centuries. “The complexity of Andean cropping systems had no precedent in Europe,” says James Lang, author of Notes of a Potato Watcher. It was “geared to every nuance of altitude and rainfall.” In other words, the conquistadors had a lot of catching up to do.9 They could have learned a great deal that they could have passed on to people farming potatoes in the Canary Islands, who could have in turn passed the knowledge to those who began to farm potatoes in Europe. But this did not happen. As a result, by the time the late blight was moving across continental Europe and then to England and Ireland, nearly all the potatoes were of a single highly productive variety, the lumper, and they were being farmed in new ways, recently invented by Europeans, invented without the biology of the potato or its pathogens very much in mind.10

Everything the British government and agricultural scientists urged Irish potato farmers to do, and nearly all the choices the farmers themselves made, sped up the spread of late blight. First, the potatoes were planted as monocultures, on which the Irish depended exclusively for their sustenance. We tell ourselves, “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket or all your fields in one crop,” yet we do anyway. Second, the British urged the Irish to abandon their traditional raised-field planting technique and instead to plow their fields. This made conditions better for late blight, inasmuch as the raised fields (akin to those used in the Andes) increased temperatures enough to kill the pathogen. The flat, plowed fields, on the other hand, made life easier for late blight.

In addition, Andeans replanted their fields with seed potatoes, but they also paid attention to and used those potatoes that resulted from true seeds. The seeds of potatoes are harder to work with. They are unpredictable (the seed of a potato can produce a potato very different from the one out of which it has grown, thanks to the genes carried in pollen).11 Yet Andean farmers knew (and know) to keep an eye out for those occasions when true potato seeds yield, at the end of fields or elsewhere, varieties that taste better, grow faster, or, in this case, don’t die from a pathogen killing everything else. The Irish and other Europeans, by contrast, replanted each year exclusively using hunks of potatoes, hunks that are confusingly called seed potatoes. Cultivating a seed potato is the sort of thing you can do as an after-school project using a glass of water and toothpicks. Choose an old potato from your cabinet, one with a sprouting eye. Replant it. That will be enough to restock your potatoes forever, so long as conditions are good and unchanging.

In some cases Irish farmers didn’t seem to have known that potato seeds could be used to grow a potato. Of course using seed potatoes ensured that the following year’s potatoes would be clones of those that were originally planted (and for this reason, Andeans also mostly plant seed potatoes). If the first generation of potatoes grows fast, this is great. But an advantage in the short term can be a disadvantage in the long term. The Irish had not, until the arrival of late blight, had a chance to learn about that disadvantage. As a result, nearly all the potatoes in Ireland were genetically identical to each other and genetically identical to every other potato that had ever been planted in Ireland. To the extent that any differences existed, they were attributable to chance mutations, most of which tended to be deleterious.

In many cases what results after a tragedy like the Irish potato famine is that, very quickly, any lessons that might be learned are forgotten by most people. Tragedies of our ancestors seem remote to our ordinary lives. Often, though, a few individuals (or institutions) remember and learn. The progress of civilization and our hope that it continues depends disproportionately on these few. For example, while most of the world all but ignored the traditional knowledge held by the Andeans about potatoes during the potato famine, after the potato famine and through to today, a few scholars paid attention. Their work has begun to pay off, which is important not only because potatoes suffer from many different problems but also because the late blight of potatoes never went away. Scientists have started to examine whether any of the Andean potato varieties are resistant to late blight. This is something you might imagine would have happened in the late 1800s. It didn’t. It is just happening now, and it is only possible because of an amazing act of foresight almost half a century earlier—an act of foresight, luck, and, to some extent, a reliable truck.

In 1971, the Peruvian government created the International Potato Center (CIP, or Centro Internacional de la Papa). One goal of the center was (and is) to study and conserve the traditional varieties of the potato and other crops of Peru for the people of Peru and for the world. It was to be (and is) one of eleven such centers, each of which is dedicated to a different sort of crop in a different region; the centers are loosely coordinated by CGIAR, the Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research.12 By 1982, the center’s collection was large: it included thousands of varieties of potatoes, not to mention other crops. It was successful. It was also in jeopardy.

In 1982, the country was in the midst of a guerrilla-led civil war in which the Marxist guerrillas, the Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path), made daily life both difficult and terrifying for many Peruvians. For example, the Sendero Luminoso arrived at one of the main agricultural stations where native Andean crops, including potatoes, were being farmed and conserved, in Ayacucho. They surrounded the station bearing lit torches and prepared to burn it down.13 The scientists feared for their lives and ran. But a campesino, a poor farmer, stepped forward. He begged the Sendero Luminoso to leave the collection be, not because the scientists needed the seeds and potatoes but because the farmers, the people, needed them. It worked. Or at least it bought the scientists time.

According to James Lang, in Notes of a Potato Watcher, Carlos Arbizu, an agronomist employed at the time by the National University in Ayacucho, decided he must move the collection. At the urging of the head of the station, he packed as much of it as he could into his truck and drove off. The next night, the Sendero Luminoso destroyed the building in which the seeds, tubers, and roots had been stored. Arbizu was still driving when it happened. In Lang’s telling, Arbizu asked people, in any village in the high Andes in which he could safely stop, to plant and care for some of the tubers and seeds. Later, Arbizu went back to the villages to collect some of the samples for the nation. The farmers had kept farming many of the varieties that they liked and, in doing so, helped save them.

Today the International Potato Center has expanded its collection and mission far beyond what might have seemed possible in the hard years of the Sendero Luminoso. The center saves and studies potatoes of nine different subspecies, some of them cones, some crescents; some red, some blue, some purple; some rich in protein, others in vitamin C. The center also works to save other traditional Andean root and tuber crops that never made it back with Pizarro or other conquistadors. Oca. Mashua. Ulluco. Maca. Arracacha. Mauka. Ahipa. Yacón. Achira. Each one neglected, threatened, and special in some way. The center also continues to try to find lost varieties of traditional crops and to study and use and make available the unique values of those varieties, whether they be flavors or types of resistance. Until recently, the consensus in scientific literature was that no known potato variety could resist potato blight. But that consensus turned out to be premature. In fact Andean potato varieties differ from one another in nearly every attribute, including their resistance to blight. This is not surprising; it just wasn’t known.

In 2014, Willmer Pérez, a scientist at the International Potato Center, started to check traditional potato varieties for their resistance to late blight. Nineteen of the 468 varieties tested, distributed across seven species, were highly resistant to at least one form of blight.14 Pérez has yet to check the many hundreds of varieties in the potato center’s collection, much less the more than four thousand varieties of potatoes grown in the Andean highlands of Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador. He hasn’t checked them for resistance to blight, nor has anyone checked most of them for resistance to fungal, bacterial, or viral pathogens or insect pests for that matter. Pérez has struggled to find money to support this work and can only do so much on his own. Too many potatoes, too little time.15

Meanwhile, farms in Ireland still plant just the handful of potato varieties brought back by the conquistadors, none of which is resistant to blight. It took just a few decades for Pizarro and other conquistadors to travel from Spain to the Inca Empire, conquer it, and bring back the potato. It has taken nearly five hundred years, though, to appreciate the real treasures of that empire—its wild diversity of crops and its inhabitants’ knowledge of them.16 Today, our knowledge is out in the world, as was Berkeley’s during the famine. It has been published by scientists, but it is as of yet without consequence. Failures of communication persist.

If we were to live through the potato famine again, one would hope that we would be quicker to learn from new scientific studies of crops and their enemies as well as from ancient traditional knowledge. Of course the easiest solution is simply to avoid moving the pests and pathogens that affect crops around the world. Indeed, having benefited from moving crops far away from their pests and pathogens, we are rather careless about reuniting them. As the writer David Quammen has observed, “Everything, including pestilence, comes from somewhere.” The blight came from somewhere, and knowledge of its source can (or might, anyway) help prevent the recurrence of blight in the future. Until the work of Tom Gilbert and Jean Ristaino was published, we didn’t have that knowledge.

Tom Gilbert is a clever British boy wonder of a scientist who is often described (not entirely truthfully) as the youngest full professor in Europe. Tom works at the Natural History Museum of Denmark, where I work during the summers. There he specializes in coming up with technically challenging but novel approaches to dealing with hard problems—the kind of problem doesn’t really matter, so long as genes are involved. Tom hates easy problems. Hard problems, on the other hand, make him giddy, or at least giddy in a dry, British kind of way. Among other things, he has attempted to sequence the genes of the extinct great auk (successfully, Tom would add if he were here). Other projects involve giant squid, the evolution of pigeons (which entailed a lot of pigeon shooting in the middle of European cities), and an attempt to figure out the kind of wine a person is drinking based on the DNA present in the bottle (which would allow counterfeit wines to be identified). It is this latter project that explains, I assume, why the last time I visited Tom’s office I saw a cooler marked ROYAL WINE, in which one could find hundred-year-old bottles from the cellar of Queen Margrethe. A visit to Tom’s office is likely to yield a cup of coffee, a very good conversation, and an interruption by some student who stumbles in, eager to ask a question about, say, the sample of vampire bat blood she holds in her hand.

Jean Ristaino, on the other hand, is a plant pathologist. Plant pathologists study the fungi, oomycetes, viruses, and bacteria that kill plants. The direct intellectual descendants of Miles Berkeley and Heinrich Anton de Bary, they use every tool available to identify pathogens. Their work is what saves our crops from destruction again and again—or fails to. And yet because their work is not viewed as sexy, or the next big thing, plant pathologists have become increasingly rare. Even as universities get bigger, they tend to have more biologists who focus on applying a method cleverly and fewer plant pathologists and other biologists skilled in knowing an organism well (more Toms and fewer Jeans).

Jean Ristaino has spent her career studying potato blight. She desperately wants to understand it, not just because of its important history but also because we still have not escaped it. Among the most vexing aspects of the story of blight has been the question of where it came from and whether the blight we are dealing with today is the same one that was present in the 1840s in Ireland and the rest of Europe. In theory, one could compare samples of the two, but in practice so little biology was being done during the nineteenth-century blight that few samples were taken. But Ristaino persevered and found some samples in European and US herbaria (collections of dried plants). In 2001, she showed that she could find DNA in the old samples and use it to identify the strain of the late blight of 1845, which she revealed was not the same as the one then present (in 2001) in Ireland or the one that was widespread globally in the mid-twentieth century.17 The next step was to consider the old blight’s code in detail, and that’s where Tom Gilbert came in. After seeing Ristaino’s announcement that she had found blight DNA from the old samples, he enlisted someone in his lab to decode it. That someone was Mike Martin. Here, in this collaboration between Tom, Mike, and Jean, lay the great hope for understanding late blight as well as the sort of approach that might help us to make sense of the many species that threaten our crops.

When Mike and Tom found and decoded the DNA in the old samples, they and Jean were in for several surprises. First, the late blight that caused the Irish potato famine appeared to be one most closely related to blights found today in the Andes. (Others had suggested Mexico; a minor, sometimes nasty, war persists as to who is right. The war’s resolution is tipping toward the Andes, or at least it seems so from my perspective, which is influenced by my conversations with Jean and Tom.) This suggested that the blight was an ancient adversary of potatoes. It also suggested that in the 1840s someone unintentionally brought the blight over from the Andes into an environment where the potato was far less protected than it would ever have been in its native land (first through movement to the ports of New York and Philadelphia and then on to Belgium). Some people have suggested that this dispersal occurred when potato biologists were trying to find less degenerate seed potatoes in the years leading up the appearance of the late blight in Europe. Others suggest that it occurred when a few potatoes traveled in a shipment of guano (fertilizer) from the Peruvian coast. Perhaps the truth lies in some mix of the two.

Subsequent studies have revealed more surprises. First, the strain of late blight from 1845 is not extinct.18 It can still be found in both Mexico and Ecuador, lurking like the ghost of horrors past.19 Second, the blight currently found in Ireland is not the same strain. Third, the blight currently found in Ireland is diverse; it is not a blight but rather several blights, which appear to have been introduced to Ireland after the potato famine. Even after more than one and a half million people died as a result of the potato blight, we still kept introducing new kinds of blight, even though we failed to introduce new kinds of potatoes. Worse than that, not only are the strains of late blight in both Europe and North America now diverse, they also include strains that resist some of our best fungicides. The new strains of blight include sexual and asexual forms. They even include newly evolved forms, some of which are more dangerous and aggressive than any potato blights ever seen before. The blight does not learn, but in response to natural selection (and with our actions as aid), it has done everything right to ensure its success. On behalf of the potato, we continue to do everything wrong.20

Each thing that happened to the potato in Ireland could happen to almost any of the plants we most depend on anywhere. It could happen because of an oomycete, a fungus, a virus, or an insect. When it does, we will depend on the knowledge—and actions—of scientists and other scholars.

For example, having contributed his ideas to the discussion of the blight, Miles Berkeley simply hoped that someone else would act upon those ideas, and his behavior suited the norms of the time. As decades have passed, the role of scientists in society has changed in some ways. Many scientists, even those focused on very basic problems, now view engaging policy makers and the public as part of their jobs. Land-grant institutions in the United States, such as the one at which I work, were founded in part to make just this connection. But nonetheless, the number of specialists trained to save a particular crop is, in almost all cases, very few. As a result, whether a crop is saved in the nick of time (or, far more rarely, well in advance) almost inevitably depends on the actions of just one or a small handful of individuals—poorly funded individuals, tired individuals, dedicated individuals who love crops or even pests and pathogens far more than reason suggests is normal. Historians dislike the “great person” version of history. Structures, policies, and social trends, they say, matter as much as does a single person or a small group of people. Certainly this was true in the case of the potato blight. One reason that the famine was so terrible had to do with the policies of the British and their belief that the free market could solve anything. But it is also true that had one or another scientist acted sufficiently decisively, things might have been different. The same has proved to be true in dozens of cases since. A great deal depends upon a tiny handful of scientists, and the situation, if anything, is getting worse. The number of pests and pathogens threatening crops is increasing faster than the number of specialists trained to fight them.

During the years between 1845 and today, new pathogens and pests have threatened every major crop. But in the years between 2006 and 2016, the rate of these new threats has accelerated. What used to be a slow tap, tap, tap on the thin ice of civilization has turned into a pounding, drumming announcement. And just as the potato blight, in retrospect, has specific causes, many of them preventable, so do the new, dangerous pathogens and pests on the rise among crops today. Having failed to learn crucial lessons from the potato famine, we were doomed to repeatedly revisit our errors (and, when we do, to hope that someone saves us from our own mistakes in time). But we can also see them with greater clarity as consequences of basic laws of nature. Among those laws is the law of area, which says that the larger the area planted, the more likely it is that a crop will be colonized by ever-more-novel pests. In Africa, no crop offers a bigger target than cassava, a crop on which hundreds of millions of people depend, just as the Irish once depended on the potato.