So ya wanna engage in some rope bondage, eh? OK, then it would make sense for you to learn a little bit about rope. Let’s take a closer look at it.

AN INTRODUCTION TO ROPE

When many people (including, by the way, me) think of bondage, they think of someone tied up with rope.

Certainly, from our earliest days of “cowboys and Indians” games, the idea of using rope to tie someone up is well established. (I remember when I was four years old, although I wasn’t specifically into bondage at the time, begging my mother for a comic book specifically because it had a picture of Dale Evans tied up in it. For some strange reason, that picture fascinated me.)

So, if rope bondage involves, well, rope, what should we know about it?

Rope: A closer look. Various types of rope are sold all over the place. In fact, if I suddenly need some rope and have none (as has occasionally happened to me), I can run down to my local convenience store and probably buy some rope that will usually be at least minimally adequate for my nefarious purposes. Indeed, I can get all the material I need for a pretty good SM scene at my local convenience store. Let’s see, in addition to rope, they sell clothespins, duct tape, candles, ice cubes, matches, Ben Gay, elastic bandages, first aid tape, knives, fly swatters, wooden spoons, and… Hey, when did this place turn into an adult toy store?

Anyway, there are various types of rope readily available for purchase. As a bondage fan, you should know at least something about the various types of rope on the market. Let’s take a look at the major aspects of ropes.

There are two basic designs of ropes: twisted rope and braided rope. What’s the difference? Well….

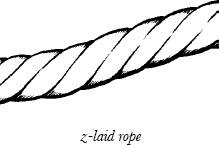

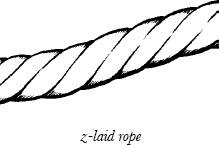

Twisted rope. The type of rope often sold as “twisted rope” is more properly called laid rope (it’s also sometimes called hawser laid rope or three-strand rope). Laid rope is constructed of strands of rope (usually, as I mentioned, three) twisted together to give it a sort of “barber pole” appearance. A real rope purist is capable of saying about laid rope: “Fibers are combined to make a yarn. Yarns are combined to make a strand. Strands are combined to make a laid rope.”

This type of rope is called a laid rope because the direction of its twist is called its “lay.” There are two types of lays: “S” laid (also called left-laid) and “Z” laid (also called right-laid). To determine the lay of a rope, hold it upright and note the direction of the twists. An S-laid rope will twist from left to right as you look from top to bottom (thus looking like the center part of the letter “S”). A Z-laid rope will twist from right to left as you look from top to bottom (thus looking like the center part of the letter “Z). Most laid rope is Z-laid rope.

I will bow before the pressures of popular usage and henceforth refer to laid rope as twisted rope.

Twisted rope is very popular for decorative use and, in addition to being sold in places such as hardware stores and boating stores, is often sold in fabric stores as trim for pillows, curtains, and so forth. It comes in a wide variety of colors, materials, and thicknesses.

From a bondage point of view, twisted rope can leave a distinctly telltale pattern on the skin of a person who has been bound with it. This pattern usually disappears within a few hours unless the bondage was especially tight. How bottoms feel about having this telltale pattern on their skin varies. (How bottoms feel about everything varies.)

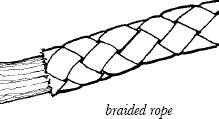

Braided rope. Braided rope is usually made of a braided outer sheath consisting of 16 or more strands. This outer sheath usually encloses an inner core strand of yarns (that is sometimes called a “heart strand”). This inner core is sometimes itself made of braided rope (often not as tightly braided as the outer sheath), but can also be made of twisted rope or of another material entirely.

Occasionally braided rope is made of four stands of twisted rope (two S-laid and two Z-laid) braided together.

Some braided ropes, particularly the smaller-diameter ones, have no inner core. This type of rope is often sold as “solid braid” rope.

ROPE MATERIALS

What is rope made of? There are two general categories of rope materials: natural and synthetic.

Natural Materials. Natural materials include cotton, hemp, sisal, and manila, with cotton and sisal being somewhat more commonly available in the United States.

Sisal rope is very inexpensive (it’s often the cheapest type of rope readily available) but usually feels very scratchy to the skin. With the exception of people who like their bondage to be painfully chafing, it is not a popular rope for bondage and is thus only rarely used. Hemp and manila rope are also rarely used for bondage.

Cotton rope is fairly soft, particularly after it’s been washed a few times, and tends to work well for bondage. However, a lot of cotton rope, particularly that made for use as clothesline, is in fact a braided cotton sheath over a core of some other material – frequently some type of plastic. This type of material may do in a “bondage emergency” (remember my need for a quick trip to the local convenience store?), but in general it is not all that good for bondage.

Rope made entirely out of cotton can work very well for bondage. Unfortunately, it can be somewhat difficult to find. One place that can be a source for pure cotton rope is a magician’s supply house. The soft, supple “magician’s rope” that they use for their performances can work very well for general bondage. (An important safety warning here: While magician’s rope can work well for “plain ordinary people tying,” it is somewhat more stretchable than some other types of rope, and is usually not rated in terms of its breaking strength, so I definitely do not recommend using this type of rope for doing any sort of suspension bondage.)

One type of rope that can work well for bondage and is fairly widely available at places like hardware stores and variety stores is called sash cord. However, you need to read the label closely. Some brands of sash cord contain no cotton at all. Other brands of “cotton” sash cord do indeed have a cotton outer sheath but their core is made of synthetic (or even “unknown”) materials.

Synthetic materials. Some synthetic materials commonly used to make rope include nylon, polyester, and polypropylene. There are many types of nylon rope on the market, and it is a very popular rope for bondage. It is generally soft on the skin (although that can vary) and comes in a variety of colors and thicknesses. One major disadvantage of nylon rope is that, because its outer sheath can be very smooth, it is sometimes difficult to get to hold a knot properly.

“How close together can you get your elbows?”

Polyester and polypropylene ropes are often sold in hardware stores and boating stores. They are popular rope materials and can work well, but unless a rope made of such materials was manufactured with the expectation that it would be repeatedly exposed to wet environments, it may not stand up well to repeated washings. (More on this later.)

Two special categories of ropes. There are two special categories of ropes that can be truly excellent for bondage. These can be thought of generally as climbing ropes and boating ropes. (Nautical types, of course, refer to ropes as lines.) As you may have guessed, you will probably have to contact either a climbing supply store, a boating supply store, or an outdoor adventure store if you want to buy some of these types of ropes. They are often noticeably more expensive than ordinary ropes, but they give excellent value for the money.

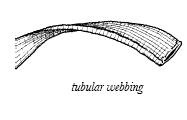

The two types of climbing ropes that we bondage fans should know about are called tubular webbing and accessory cord (also sometimes called Prussick cord). Let’s take a closer look at each.

Tubular webbing. There is a special type of nylon “rope” that every bondage enthusiast should at least know about. It’s called tubular webbing and has so many fans that it has something of a cult following.

There are basically two types of webbing: flat webbing (sometimes called seat-belt webbing) and tubular webbing. Both are a type of “flat rope” and are often used as accessory ropes, but not the main ropes, for mountain climbing and rescue work. Flat webbing and tubular webbing look similar at a distance, but upon close examination of an unsealed end you can see that tubular webbing can be “pinched open” to reveal a channel while flat webbing has no such channel and is more similar to the webbing found in seat belts.

Flat webbing tends to be somewhat stiffer than tubular webbing, and generally does not hold knots as well as tubular webbing, so it is not used very often for bondage.

Tubular webbing is available in widths of (approximately) half-inch, one-inch, and two-inch. Both the half-inch and the one-inch thicknesses are popular for bondage, with the half-inch thickness possibly being the more popular.

Tubular webbing can work very well for bondage purposes. There are a number of reasons for this:

• Tubular webbing is more “tape-shaped” than “rope-shaped” so it tends to lie flatter on the skin and thus distribute its force over a wider area. This quality can reduce the amount of marking left on the skin.

• Tubular webbing can be bought in a wide variety of colors. One vendor lists it for sale in orange, blue, red, purple, black, green, and yellow.

• Tubular webbing usually comes off the spool in an acceptably soft state. It can become even softer with a few washings.

• Tubular webbing withstands washing very well. Remember, though, that it’s nylon and therefore it will melt if exposed to high levels of heat. Avoid putting tubular webbing in your dryer until you’ve first made certain that you’ve set your dryer to either “low heat” or “no heat,” unless you want a bunch of melted nylon messing up your dryer. In general, it’s probably best to let tubular webbing (and all other ropes made of synthetic materials) simply air dry.

• Tubular webbing is very strong. Some brands of one-inch “mil-spec” (built to military specifications) webbing is rated at a strength of about 4,000 pounds. Some brands of half-inch webbing are rated to a strength of about 1500 pounds, and some are rated even higher. Even the lowest strength rating of tubular webbing should be much more than adequate for the bondage purposes set forth in this book.

Tubular webbing can be noticeably more expensive than ordinary rope, but given that it can easily last for more than a decade, many bondage people consider tubular webbing to be much more than worth the extra cost.

Climbing rope — another special type of nylon rope. Climbing rope — or, to put it more correctly, the rope sold in stores that sell mountain climbing supplies — is another type of nylon rope that can work very well for bondage purposes. However, I should note that the types of ropes most often used for the actual “hold a person in mid-air” type of climbing applications are usually around one-half an inch in thickness, and that is a little too thick for most bondage fans. Instead of using actual climbing rope (which, among other things, can be very expensive) we bondage fans tend to use the smaller-diameter “accessory cord” that such stores sell.

Note: The diameter of accessory cord is usually expressed in millimeters, not fractions of an inch. Keeping in mind that one inch equals 2.54 centimeters o25.4 millimeters, remember that six-millimeter or seven-millimeter rope is about one-quarter of an inch in thickness and that eight-millimeter rope is about five-sixteenths of an inch in thickness, and that nine-millimeter to ten-millimeter rope is about three-eighths of an inch in thickness.

“Have you seen the red tubular webbing any-where?”

Like tubular webbing, the type of rope known as climbing accessory cord can work very well for bondage, and shares many of the excellent qualities of tubular webbing. While accessory cord does not lie as flat on the skin as tubular webbing does, it comes in an even wider variety of colors, including mixed colors as well as single colors. (For my money, it’s by far the prettiest type of rope used for bondage.) It also frequently is acceptably soft when bought “off the spool” and usually becomes even softer with a few washings. It withstands washing well, is very strong, and the ends are relatively easy to seal. Like tubular webbing, and all other forms of rope made from synthetic materials, it was not designed to stand up to high heat, so you should avoid tossing it into a clothes dryer.

Boating rope. Other types of rope that can be truly excellent for bondage purposes are the ropes (more properly called lines) sold in boating supply stores. These are available as either twisted ropes or braided ropes, and are commonly made of either nylon or polyester. They come in several different colors and many different widths, especially the braided ropes. Boating ropes also stand up very well to repeated washings. (Please note that I did not find this to be especially true of the nylon, polyester, or polypropylene ropes that I bought in hardware stores, particularly the braided ropes that had a core.)

Also, boating lines are rated in terms of their stretchiness in a way that climbing ropes are not. Most rope used for bondage is somewhat stretchy, and tends to “give” a bit once it’s been on the bottom’s body for a while. Being bound with low-stretch boating line can be an entirely different matter. As I can tell you from experience, being tied up with this stuff can feel like you have been positively encased.

Boating line can be somewhat stiff when you first get it home from the store, but with a few washings it can become amazingly soft and supple. I’ve found this to be particularly true of braided boating rope.

Boating rope: It’s definitely worth checking this stuff out.

Big Savings Hint: Both climbing stores and boating stores often have something along the lines of what’s called a “rope remnant bin.” This bin will contain lengths of rope that have been left over from other cuttings, have been returned for one reason or another by customers, and so forth. Such ropes will typically be too short for their “legitimate” uses, but will do very nicely for our nefarious plans. Additionally, such remnants are usually for sale at a far cheaper price than the off-the-spool ropes cost. I have picked up some tasty bargains on very high-quality ropes this way. (This one tip may save you more than you paid for this book.)

Stretchiness. All ropes and all rope-like materials have at least some degree of stretchiness (more properly called degree of elongation). This is true even for chains. However, this degree of stretchiness can vary widely; nylon rope and pure cotton rope often have the most stretchiness.

Warning: Stretchiness can build up significant tension. The package that comes with the rope may contain a safety advisory to never stand in line with a rope under tension. In particular, nylon rope may store up a very large amount of energy while under tension, and if it breaks it may have a “snap back” potential that can be outright deadly.

In general, I recommend materials of relatively low stretch for bondage. I’ve tried using very stretchable materials, such as bungee cords, for bondage, and have usually found the results very disappointing. In particular, in order to apply the material tightly enough to prevent the bottom from easily escaping, it is usually necessary to apply it so tightly that it creates a dangerous and damaging amount of pressure on the bound tissues.

Also, because all rope used for bondage will stretch out at least somewhat over time, a cunning bottom may know that all they have to do is wait patiently. A rope whose tightness was definitely inescapable when it was first applied may loosen over time to the point where it can be easily escaped. Using low-stretch ropes can definitely help prevent this eventuality.

Stretchiness is often described in terms of a rope’s percent of stretch at what is called “safe working load.” What is considered “safe working load” varies, but is usually considered to be somewhere around 15% of the load at which the rope is expected to break. Most bondage-related uses of rope, other than special applications such as suspension bondage, are not likely to stress a rope to anything close to its breaking strength. This is true even if the rope’s core has been removed. (See p. 98.)

One of the nice things about buying rope at climbing stores or boating stores is that a rope’s degree of elongation is often numerically quantified as one of its various specifications. In particular, many types of boating rope stretch less than two percent at their safe working load.

At the climbing store, actual climbing “hold a person in the air” rope may be sold as “dynamic” and “static” rope, with the static rope having much less stretch to it. However, both such ropes are often too wide for routine bondage use. The accessory cord and the tubular webbing sold in such stores seems to be fairly low-stretch ropes.

Width. One of the more important questions regarding rope that will be used for erotic bondage is the question of how wide it should be. This is, as always, something of a matter of taste. I’ve seen everything from very thick mountain climbing ropes down to the thinnest dental floss used for bondage.

In thinking about how wide bondage rope should be, it helps to keep the principle of “acceptable pressure” in mind. People usually want their bondage to be tight enough to prevent escape but loose enough to not damage the bottom. Tightness is a matter of pressure.

Basic physics: Pressure is defined as the amount of force divided by the amount of area. Thus, lots of force applied to a small area equals high pressure. Alternatively, very little force applied to a large area equals low pressure.

What does this mean to us bondage fans? Basically, the thinner the rope we use, the more “wraps” of rope we need to distribute the pressure on the bound body part enough to keep it within tolerable limits.

While tastes vary, most bondage folks seem to end up preferring to use ropes that are about one-quarter-inch — aka 4/16 of an inch (4/16”) — in thickness. Some people prefer a 5/16” thickness in their ropes, and some go up to 3/8” (6/16”) in thickness.

Rope that is thicker than 3/8” is usually not used for bondage, except for special applications such as suspension bondage. (The one significant exception that I’ve found to this is one-inch-wide tubular webbing.) Some people like rope that is somewhat thinner than 1/4” (4/16”) so they may use 3/16” thick rope or even the one-eighth-inch (2/16”) thick “parachute cord” rope, but if they do then they usually need to use more wraps around the bound body part than people who use thicker ropes need to use.

One place where thinner ropes can work especially well is for breast and genital bondage. (More on those very interesting topics later.)

For your “bondage starter kit” I recommend that you buy rope that is either1/4” (4/16”) or 5/16” thick.

PREPARING THE ROPE

Length. The question always comes up: how long should the ropes I use for bondage be? As always, this is a matter of taste, but I have found that rope lengths which are either about six feet long or multiples of six feet long – such as 12-foot, 18-foot, 24-foot lengths – tend to be the most generally useful.

“Can I be tied up while we watch that video?”

Big hint: As a general rule, it’s both easier and more effective to work with several shorter lengths of rope than it is with one very long length. Using shorter lengths makes the bondage easier to adjust to a particular bottom. Plus, if you have to rearrange one part of it, you don’t have to undo everything that you applied after that part.

For example, let’s say that I buy a 50-foot length of rope at my local hardware store and want to prepare it for bondage use. A 50-foot length is itself pretty long for all but the most exceptional usages, such as an elaborate body harness, so I probably want to cut it. It’s logical to cut it in half, so that gives me two lengths, each 25 feet in length. This is pretty good for a comprehensive all-body tie, but it’s still long enough that using it, and especially readjusting it, can be awkward.

By the way, when making the cuts in your new ropes, I suggest that you use your EMT scissors. It can be a good idea to get as much familiarity as possible regarding how well your scissors cut ropes before trying to use them in an actual emergency.

So you cut the 25-foot length in half and this gives you two (approximately) 12-foot lengths. Now you’re getting somewhere. The 12-foot length frequently works very well for a wide variety of purposes. It fact, I would say that the 12-foot length of rope is the most useful overall length for bondage purposes.

If you cut the 12-foot length in half, this will, of course, give you two lengths of rope, each six feet long. This is about as short a length as you want for most bondage purposes. I’ve found that the six-foot rope often works especially well for tying the bottom’s ankles or knees together, or for tying their legs out in a spread-eagle fashion. However, it’s often too short for tying wrists either together or separately outstretched in a “spread-eagle” position. I’ll explain why this is so later on.

Given all of the above, you could make a pretty good “bondage starter kit” out of you 50-foot rope by cutting it until you have two 12-foot lengths and four 6-foot lengths.

An 18-foot length can be especially useful for tying the bottom’s hands behind their back (I’ll explain the technique later). So if you had a 100-foot length, you might create a “bondage starter kit” as follows:

First cut the 100-foot length of rope in half, then cut one of those halves into four lengths of rope, each just slightly longer than twelve feet long.

Next, take the second 50-foot length of rope, and cut it in half to make two 25-foot lengths. Keep cutting one of those 25-foot lengths in half until you have four six-foot lengths. Then (please pay especially close attention here) use one of those six-foot lengths to measure out a six-foot length on the remaining uncut 25-foot rope and make a single cut in it. This will give you one (approximately) 18-foot length of rope and an additional six-foot length.

Your overall total will be: One 18-foot length, four 12-foot lengths, and five six-foot lengths. A very nice “starter kit” indeed.

Removing the core. Braided rope, unless it’s “solid braid” rope, will consist of an outer sheath and an inner core. One interesting approach to preparing this rope for use in bondage is to remove its core. (Obviously, this will have to be done before you seal the rope’s ends shut.) Removing the rope’s inner core will do a number of things to the rope.

First, obviously removing the core of a rope will weaken it considerably — by as much as 70%, according to some estimates. For applications such as suspension bondage, this could create a very dangerous situation. However, for “plain, ordinary people-tying,” removing the core seems to create no significant problems. Most of the ropes I recommend for bondage still remain more than strong enough for our purposes.

Second, and more to the point, removing the core converts the rope into a sort of especially narrow tubular webbing. This means that the rope will now tend to become much more flexible and easy to work with, and to lie flatter on the skin. The increase in flexibility frequently makes it possible to use the rope much more effectively for bondage as it can be molded more closely to the bottom’s body.

“I need another 12-foot length for that.”

Third, removing the rope’s core will tend to allow the rope to stretch out in length a bit more, making the remaining sheath slightly longer than it was.

Braided ropes are made of either natural or synthetic materials. In general, I’ve found that removing the core from a rope made of synthetic materials to be relatively easy, but removing the core from a rope made of a natural material, such as cotton, can be a challenge.

To remove the core from a “challenging” rope, consider the following tips:

First, it may be a good idea to first cut your rope into the desired lengths. You will likely find that it is much easier to remove the core from several short lengths of rope than it is to remove the core from a single long length of rope.

Second, it may be a very good idea to wear some sort of sturdy gloves, such as a leather gardening gloves, while trying to work out the core. Otherwise, you increase your chances of getting what you might think of as “rope splinters” in your hands.

Third, the process may go significantly easier, particularly when working with a longer length of rope, if you pull out a few inches of the core and tie this core around a fairly sturdy, immovable object such as a strong part of a stairway banister.

To remove the core, the basic process is: pull out several inches of core (perhaps winding the core around your gloved hand as you go) until it resists further such pulling. Then straighten out the bunched-up outer sheath — this usually works better if you work from the far end to the near end — and repeat as necessary.

I suggest that if you have four lengths of rope, each twelve feet long, you remove the core from two lengths and leave the core in the other two, then compare how they perform.

Sealing the ends. OK, you’re just back from the store and with you is your newly bought 50-foot length of braided rope that you plan to use for bondage. Excellent.

However, before you haul out your EMT scissors and start cutting away, it is only wise to give a moment of thought to contemplate what will happen to the ends of rope that will be created by this cutting.

What will happen, unless you prevent it from happening, is that the ends will immediately start to fray. This will result in an untidy-looking mess of loose strands at the ends of your ropes. (If you use twisted rope, this effect can be even more pronounced as the strands can actually spin, unwinding the rope for quite some distance and looking really messy.) Remember that messiness and sloppiness are often considered to be ominous signs, particularly in a top.

So, how does one go about keeping the ends from fraying? Let me count the ways. (More than a dozen are listed below. This was one aspect of researching this book that turned into something of an odyssey.)

There are several different categories of end-sealing techniques. These can be roughly categorized as chemically sealing the ends, taping the ends, sewing the ends, and melting the ends. Let me describe each in turn.

1. Chemically sealing the ends. In this approach, various types of liquid chemicals that harden upon drying are applied to the ends, thus sealing them.

• A liquid rope sealer. There are compounds specifically intended for this usage that is sold in boating supply stores and in climbing stores. While this compound is usually sold in a clear version, it is also possible to buy it in red, white, and green. (The climbing vendors seem to stock a wider variety of colors than the boating vendors.)

Because you will probably be trying to seal an end created by a fresh cut, I suggest the following approach: Find the point in the rope where you wish to make your cut, then “paint” that section of the rope with about a one-inch wideband of sealant. (Some brands of sealant come with a convenient brush that facilitates this process.) Allow the sealant to dry, then cut through this coat with your scissors. If you did an adequate job, the ends will not fray. As a finishing touch, you can then dip the ends in the sealant one last time to entirely cover the ends. Use the brush to remove any obvious excess dip solution, and you’re done. This kind of sealant can work particularly well when dealing with relatively large ropes such as the 3/8” diameter.

• Tool dip. My local hardware stores sell a special sealant known as “tool dip” that can work well for sealing the ends of ropes. This material does not come with a brush so it doesn’t work as well for painting a section prior to cutting. Of course, one can simply fold the rope into what’s called, in roper speak, a “bight” and put the bight into the dip. As with the rope sealant, you may need to do a second dip of the freshly cut ends after the first coat dries. My local stores have this material available in the colors of red and black.

Note: This material uses some serious chemicals to keep the sealant dissolved. The instructions say to use this material only in a very-well-ventilated area. After using it a few times, I can certainly understand why.

• Fingernail polish. In the tests we did here at the “San Francisco Bondage Research Institute” we found that fingernail polish worked almost as well as did the more formal liquid sealant. Like many brands of the sealant, it comes with its own brush. Again, paint a one-inch band of nail polish, allow to dry, and cut through the midpoint of the dried portion. Then apply another coat to the freshly cut ends. We found that fingernail polish stands up well to repeated washings.

One of the significant benefits of using fingernail polish, aside from its ready availability and low cost, is that it is available in a truly amazing variety of colors. This can make it easier to color-code your ropes in terms of length, width, etc. Of course, clear nail polish is also available and works well for sealing rope ends while allowing the original color of the rope to show through.

Sealing ends with fingernail polish seemed, overall, noticeably less work and generally easier than using the “heavier” substances such as liquid rope whipping and tool dip. It was also easier to work with narrower-diameter ropes when using fingernail polish.

• Anti-fray liquids. Fabric stores sell various brands of “anti-fray” liquids that you can apply to different types of cloth to prevent them from unraveling. One is known as “Fray Block.” I found the sample that I bought to be even easier to work with than fingernail polish was. While “anti-fray liquid” did not seem to stand up to repeated washing as well as fingernail polish did, it did seem to stand up to such washings adequately. (Some anti-fray liquids are actually designed to wash out. Check the label.) As with the other compounds, apply about a one-inch band of solution to the place where the cut is to be made, allow to dry, make your cut, and maybe apply a bit more anti-fray to the freshly cut end.

2. Taping the ends. With this approach, you simply apply some tape to the rope in a way that keeps the ends from fraying. While you can apply tape to the ends after the cut has been made, it’s generally easier to wrap a few turns of tape (two or three wraps are usually sufficient) around the location in the rope where you want the cut to be, and then cut through the tape.

Note: Newly purchased rope often “comes home from the store” with some tape sealing its two ends. However, this tape is often masking tape or some other type of not very durable tape. I suggest that you replace it with more durable tape.

You probably won’t need to apply much more than about half an inch of tape to a rope end to seal it adequately (larger-diameter ropes may need up to one inch of tape), and longer “tape tails” can be both awkward and unsightly. This is not a problem if you’re using tape that is one inch wide. However, if you’re using wider tape, you might want to either cut the tape in half lengthwise before you apply it, or apply it and then cut off the taped end of the rope until only about half an inch is left.

Note: No brand of tape that I tested stood up really well to repeated washings. Understand therefore that you may periodically either replace the tape entirely or apply additional tape over it.

• Cloth athletic tape. This type of tape is readily available, comes in a variety of widths, and because almost all brands of it are white, this type of tape blends in well when used on standard, white ropes. Cloth athletic tape also absorbs laundry markings that may be used to indicate length in a way that duct tape may not. However, cloth athletic tape typically did not stand up to repeated washings as well as the various brands of duct tape did.

• Silver/gray duct tape. This is the classic duct tape, sometimes also known as cloth tape, that is widely sold in supermarkets, variety stores, hardware stores, etc., and frequently used in movies and television shows for bondage. (I’ll have more to say about using various types of tape for doing actual bondage later in this book.) This type of tape frequently works quite well for sealing the ends of rope. It is normally sold in two-inch widths, so you may have to make some accommodations for that (as described above). Silver/Gray duct tape tends to withstand washing fairly well, perhaps the best of any type of tape that I tested. One potential drawback is that its color doesn’t allow it to blend in well with the color of the rope it is being used on. Another potential drawback is that its slick surface often prevents permanent markings.

• Colored duct tape. This is another type of duct tape. Sometimes called “cloth tape,” it is also frequently found in hardware stores, and is sometimes also found in supermarkets, variety stores, etc. This type of tape is typically sold in two-inch widths, although I have seen it for sale in inch-and-a-half widths. The brands of colored duct tape that I tested, by and large, were not quite as sticky as the traditional silver/gray duct tape, but usually still quite sticky enough for our purposes. One advantage of this tape is, of course, that it comes in a variety of different colors, thus allowing it to be used to color-code the ropes for various purposes. (For example, different lengths of rope could have different colors of tape on their ends.)

3. Sewing the ends (and related approaches). In this approach, the ends of the rope are sealed shut with thread or some similar material. This is something of a traditional means of sealing rope ends shut and some of the knot books present numerous methods for accomplishing it.

• Tying a knot in the rope’s end. This is probably the easiest method of preventing the end of a rope from fraying. It also has the advantages of being both quick and simple to do, and needing no additional equipment whatsoever. To do this, you simply tie a basic knot such as an overhand knot (or maybe something like a figure-eight knot if you feel like getting fancy) near the end of the rope. While this will prevent fraying, it will also leave a knot of noticeable size and frequently of unesthetic appearance at the rope’s end. Such a knot can also make using the rope somewhat awkward. While the “simply tie a knot in the end” approach may work satisfactorily for very narrow-diameter ropes, such as one-eighth inch thick ropes, or may be suitable for short-term use, I have not found it to be a good, long-term solution to preventing the ends from fraying.

• Using small rubber bands. This is such a simple method that I hesitate to mention it, but I will for the sake of completeness. Among other things, you might find yourself in a situation where rubber bands are all you have available, at least temporarily.

The technique is simple enough: Simply place a rubber band over the end of a freshly cut rope, twist the rubber band, and repeat the procedure. If you’re using a relatively small rubber band, it should take only a moment to seal the end.

Obviously, this approach is, at best, a short-term solution and it would probably be wise for you to seal the ends of your ropes in a more permanent way at an early opportunity.

• Sealing with simple sewing. I’m not an expert with needle and thread, but I had quite satisfactory results by taking a fairly long length of white thread, putting it through the needle so that its midpoint was at the needle’s eye, and simply passing the needle through the end of the rope a few times. (Note: I’m talking about braided rope here.) One can use a rough figure-eight pattern here, perhaps followed by an additional figure-eight pattern perpendicular to the first one, to make sure that the entire outer surface of the rope is covered. Leave a small tail when you start and when you’re done simply tie the finishing tail tightly to the starting tail with a Square knot or Surgeon’s knot. (Do this once or twice and you should easily get the hang of it.) I have some magician’s rope whose ends I sealed this way nearly twenty years ago and now, numerous usages and washings later, they are still sealed just fine.

• Formal whip-stitching. “Whip stitching” is a time-honored, even ancient, method of keeping the ends of a rope from fraying. In this approach, several turns of a very-narrow-diameter rope are wrapped around the tip of a rope and then fastened in place. Sturdy thread is often used for this purpose, and dental floss is occasionally used. Boating stores frequently sell various types of whipping twine intended especially for this purpose. One common recommendation to wrap enough turns so that the width of the turns at least equals the diameter of the rope.

One very simple, very quick to teach method would be to take about a six-inch length of thread, tie the midpoint around the end of the rope about an inch from its end in an Overhand knot and pull tight, then wrap the thread around to the other side of the rope and tie the thread in another Overhand knot. Repeat this a few times, working toward the end of the rope, and finish the whip-stitching with a Square knot or Surgeon’s knot.

For instruction on how to do other (and better) whip-stitchings, consult this book’s Bibliography.

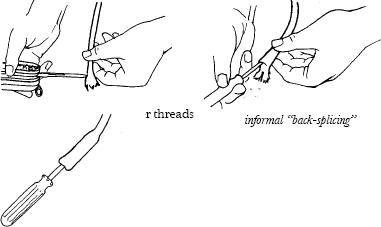

• Back-splicing. Back-splicing a rope is basically taking the frayed ends of the rope and looping them back onto the still-unfrayed portion of the rope and interweaving the two sections. Done adequately, this creates a very secure, tidy-looking rope end that is very resistant to further fraying and stands up well to repeated washings.

There are several methods to perform a back-splice, some of which date back into antiquity, but they can be classified into “formal” and “informal” methods.

“Formal” back-splicing can be done on twisted rope. However, this is a complicated technique and beyond the scope of this book. For more information, consult one of the knotcraft books in the Bibliography.

Formal back-splicing can also be done on braided rope, but is also somewhat complicated and usually requires the use of one or another special and somewhat expensive tools. These tools are usually sold in boating stores.

“Cross you ankles!”

There is an informal “back-splicing” technique which can be done on braided rope that has a core. This technique requires no special tools and can work very well. (Actually, technically, it’s not really a true back-splicing technique, but it seems to work just as well.)

To make an “informal back-splice” you will need, as I mentioned, a length of rope that has a braided outer sheath and a core. You will also likely need two tools. One will be a very narrow, fork-like device. (I found that the fishhook-remover on my Swiss Army knife worked well.) You will also need a very narrow, ramrod-like device. (I found that a 1/8” phillipshead screwdriver worked well.)

Assuming that the rope in question is about 1/4” thick, cut it where you wish, then pull out about three to four inches of the core from the braided outer sheath and cut off this part of the core. Work the braided outer sheath back out over the core as much as you can. Then take the fishhook remover and poke the outer strands of the sheath down into the hole in the interior of the rope that was created by the removal of the core. Use the screwdriver as needed to ram and pack the outer threads firmly down into place. (This may sound complicated, but it’s actually rather easy. If you have the proper tools, you should pick it up very quickly with just an attempt or two.)

When finished, there will be a slight thickening of the tip, and maybe a short section of the rope between the end-packing and the rest of the core. This is a nice technique.

4. Melting the ends. The ends of ropes made of synthetic materials, such as nylon, polyester, or polypropylene, can be very nicely sealed by applying enough heat to melt them. There are a number of ways to do this.

? Cutting with a commercially made “hot knife.” Stores that sell boating and climbing ropes frequently stock large spools of these ropes. The customer tells the clerk how much rope they want to buy, and the clerk then pulls the requested length of the rope in question off the spool and cuts it with a special device (sometimes called a “hot knife”) used specifically for this purpose. This tool usually both cuts the rope and seals the ends in the same action. If you know ahead of time what lengths of rope you wish, and you don’t want to remove the core of the rope, you can simply have the clerk do your cutting for you. For example, you might say to them “I want four twelve-foot lengths of that purple, six-millimeter accessory cord.” The clerk will usually be happy to cut the rope to your specifications.

• Heat shrinks. Heat shrinks are interesting items. They are long, hollow cylinders of rubber-like or plastic-like material whose diameter shrinks when heat is applied to them. Heat shrinks are sold in boating stores, hardware stores, and electrical supply stores. The heat shrinks that are sold in boating stores are “marine grade” and sold with the intention that they will be used to seal the ends of ropes. The heat shrinks sold in hardware and electrical supply houses are sold with the intention that they will be used to seal bundles of electrical wires together. Predictably, I had by far the better results when I used the heat shrinks that were sold by boating supply stores.

Heat shrinks are easy to use and, as with most end-sealing techniques, your ability to use them will improve rapidly with experience. To seal an end, you will need a length of heat shrink that has an interior diameter which is slightly larger than the diameter of the rope that you want to seal (1/16”-1/8” wider). To apply, cut off a length of heat shrink tubing — I suggest you cut off a length of tubing that is half again as long as the diameter of the rope that you want to seal — and slide it over the rope in question. Make your cut (through the rope only, not through the heat shrink), then slide the heat shrink out to the freshly made end. You may slide it out so that a portion of the heat shrink entirely covers the freshly cut end or you may leave the last quarter-inch or so of the rope free. (The latter approach may produce a heat shrink with a better hold on the rope.)

You will need to apply heat to the heat shrink in order to get it to shrink. (Well, duh.) I have found that using a small candle flame works excellently for this. Hold the heat shrink slightly over the candle flame and slowly rotate it. (Be careful that the flame does not affect the rope itself.) Continue carefully rotating the rope until the shrinking stops, then set the rope aside to cool. The heat shrink will be very hot at this point, so be careful where you set it. Perhaps allowing the rope tip to dangle freely in the air might be best.

In summary, I found that heat shrinks did work quite well, although some types did tend to pop off during use. This tendency seemed especially true regarding non-marine-grade heat shrinks and heat shrinks that entirely covered the free end rather than leaving a small amount of it free.

• Melting the ends. Melting the ends of a rope is a well known and widely used sealing technique, and it can work very well, provided you keep a couple of points in mind.

First, this only applies to ropes made of synthetic materials! If you try to melt the ends of your cotton sash cord you will end up looking very silly indeed.

You will need a source of significant heat for this process. As with heat shrinks, a simple candle flame usually works well. There are two basic approaches: The widely known cut-then-flame approach, and the lesser known flame-then-cut approach.

In the cut-then-flame approach, you simply cut the rope then cautiously apply the freshly cut ends to the flame. This can work just fine. In particular, tubular webbing is often excellently sealed with this approach with only a very brief exposure to the flame. (Regarding tubular webbing, please note that it’s not necessary to seal the channel shut. Simply melt the ends just a bit so they won’t fray.)

However, some types of ropes unravel quite a bit almost immediately upon being cut and melting these ends shut may be difficult. This problem may be mitigated somewhat by wrapping a small amount of tape around the rope, making your cut through the midpoint of this tape, flaming the freshly cut ends, and then removing the tape. (You may have to re-flame the ends just a bit after the tape removal.)

Sometimes the result of a cut-then-flame technique is a large, hard, ugly knob of melted rope at its end. This is particularly true if someone was a bit over enthusiastic in how long they applied the flame to the cut end. This knob can sometimes be reduced to an acceptable size by use of a nail file or something similar, but it may be easier to simply cut it off and try again.

The flame-then-cut approach can work much better. This is especially true when dealing with synthetic ropes other than tubular webbing. In this approach, first hold the section of the rope through which you want to make your cut over the candle flame, rotating it slowly until you have slightly melted and fused together some of the outer strands. Allow this section of the rope to cool before cutting it (thus keeping you from getting melted rope on your EMT scissors), then make your cut. Finally, expose the freshly cut ends as needed to the candle flame to “touch up” the sealing job. In particular, the interior portions may need some sealing. The whole process is similar to how liquid rope whipping is used.

Very early in your bondage play, you will likely start to think along the lines of “well, let’s see, I’ll need two twelve-foot lengths of rope to tie their wrists apart at the head of the bed, and I’ll also need two lengths of six-foot rope to tie their ankles apart,” and so forth. In other words, you’ll view the bondage tasks that you want to accomplish in terms of how long a length of rope you’ll need.

While you may be able to tell the difference between a six-foot length of rope and a fifty-foot length of rope of the same type and color by merely glancing at their difference in bulk, it can be much harder to tell the difference between a six-foot length and a twelve-foot length, and so forth. Thus, you bondage play can proceed much more smoothly and efficiently if you can more readily tell the different lengths apart. There are a number of solutions for this problem.

1. Color-code the ropes. One very simple, elegant, and colorful solution to this is to simply have the different lengths be of different colors. This is especially easy with ropes that are sold in different colors, such as tubular webbing. For example, you might decide to have your six-foot lengths be blue in color, your twelve-foot lengths be red, and so forth. You can buy the rope in bulk and make the cuts yourself, or if the place where you buy the rope has a “hot knife” — boating shops and climbing shops usually have such a knife — you can have the clerk make the cuts for you and to seal the ends as described above. An additional benefit of this approach is that you can tie your bottom into a very pretty package.

2. Color-code the ends of the ropes. If your ropes are all of the same color, you can often both seal and color-code the ends in various ways.

Colored duct tape (sometimes sold as cloth tape) can work very well here. Thus, six-foot lengths of rope could have their ends both sealed with green tape, twelve-foot lengths could have their ends sealed in red tape, and so forth.

You can also color-code as well as seal the ends of your ropes with nail polish of various colors. (Remember that you may have to apply more than one coat.) This technique will work better on some types of rope than on others. In particular, softer ropes may absorb the nail polish to the point where it becomes essentially invisible. Some types of tubular webbing can be particularly difficult in this regard. However, on many types of ropes, nail polish will work just fine. Note that while nail polish usually stands up well to repeated washings, an occasional touch-up may be needed.

3. Mark the rope ends with bands of permanent ink. This approach can also work well with ropes that are all of the same color and type. Let’s assume that all of your ropes are either six feet long or are multiples of six feet long. Simply take a permanent-ink marking pen (a laundry marker can work well) and make a narrow band around both ends of the rope, with each band signifying six feet of length. Thus, you would know at a glance that a rope with a single band around each end is about six feet long, a rope with two bands is about twelve feet long, a rope with three bands is about eighteen feet long, and so forth.

To fine-tune this approach a bit, you might mark a line about one inch long along a rope for each additional three feet of length. (I suggest you make two such lines on each end of the rope, each opposite the other on the rope’s diameter.) For example, if you have a rope that is nine feet and a few inches long, you might mark it with a single band and a single line. Thus, you would be able to tell at a glance at a rope’s end if it is about three feet, nine feet, etc.

You can also use permanent marking pens. These can usually be found without too much trouble in the colors of black, red, green, and blue, and those four colors should be sufficient for the four most common lengths.

Note: I tried using various types and colors of tape for this banding approach, but my results weren’t very satisfactory.

4. Marking the rope ends with thread of different colors. The ends of some ropes may be quite nicely marked simply by sewing a noticeable amount of colored thread onto them. As with using colored tape or nail polish, this approach can also be combined with sealing the ends.

Finding the rope’s midpoint. A lot of bondage techniques, especially the ones in this book, do not start at a rope’s end. Rather, they start at the rope’s midpoint. Thus, things can go a lot more smoothly if the approximate midpoint is marked on the rope in some fashion.

Marking the rope’s approximate midpoint can often be done very easily with your marking pen if the color of the pen’s ink contrasts noticeably with the rope’s color. Simply fold the rope in half, make a small mark on the rope to note the midpoint, unfold the rope, and finally mark in a band around the entire rope’s diameter.

Colored nail polish, colored thread, and a long, narrow piece of colored tape can also be used to mark the rope’s midpoint.

Please note that most types of rope have some stretch to them, and thus the rope, or various sections of it, may shrink or stretch a bit with use. Thus, no matter how carefully you initially measure your rope’s midpoint, you may find that the midpoint you so carefully marked has shifted a bit over time. Thus, midpoint markings should be taken as approximations.

Marking the quarter-point. Longer ropes, such as 24-foot ropes, are often folded in half and then used for bondage, so when using such ropes you may find it useful to mark “the midpoint of the midpoint” by making a mark at the approximate quarter-points of the rope. This can be done as described for marking the midpoint, but obviously the quarter-point marks should have a different appearance than the midpoint marks.

WASHABILITY

Interestingly enough, when considering a good rope to use for bondage purposes, the question of “washability” comes up fairly early. After all, ropes commonly go onto skin, where they will pick up dirt, sweat, and so forth. They therefore benefit from the occasional washing. Furthermore, our ropes may get certain body substances on them, including semen, saliva, vaginal fluids, blood, and traces of fecal matter. If they do, we’ll want to wash them before we use them again.

“I like this type of rope for use on larger men.”

While I know that some of you are diligent enough to wash your ropes by hand, frankly, that means you’re more diligent than I am. Most of the time, unless I have some reason to suspect that my ropes might have become especially contaminated with something infectious, I’ll settle for tossing my ropes into the washing machine along with the rest of my laundry.

Really Big Hint: I strongly suggest that you buy something commonly called a “lingerie bag.” Dumping a bunch of loose ropes into your washing machine can be asking for disaster. The loose ropes can coil around the agitator and jam it fast. Drop your ropes into a lingerie bag and then drop the bag into the washing machine for a much more hassle-free experience. (If you really can’t get a lingerie bag, you can use a knotted-shut pillowcase as an at least minimally adequate substitute – but I recommend that you go ahead and purchase a lingerie bag. Many drugstores and variety stores sell them, and they’re fairly cheap.)

Note: I’ve tried lingerie bags that zip shut and lingerie bags that snap shut, and I’ve found that the ones which snap such seem more likely come undone in the machine, thus spilling out the ropes into the machine to possibly cause problems. That being the case, I recommend that you either go with a zip-shut bag or reinforce your snap-shut bag with a large safety pin.

I’ve had it recommended to me that you can also wash your ropes in a washing machine by first knotting the rope into a chain. I’ve tried this, but I’ve had the ropes come unchained in the machine. I’m also dubious that all of the rope gets properly cleaned with this approach. Thus, while I’m not going to condemn the “chain” approach, I will stick with recommending the use of a lingerie bag.

Ropes can vary a surprising amount in their degree of washability, so I recommend that you not buy too much of any given type of rope until you’ve had a chance to test it in this regard. In general, any type of rope manufactured with the expectation that it will be used in a “wet” environment – typically an outdoor environment – will do well in the washability department. With other types of ropes, you might get a nasty surprise.

The following types of ropes usually wash well: many types of twisted ropes, boating line, tubular webbing, solid-braid ropes, accessory cord, sash cord, ropes whose cores have been removed, and braided ropes whose outer sheath and inner core are both made entirely of cotton.

The following types of rope may not wash well: Any rope that is not sold with the intention that it will be used in a “wet” environment. This would include many braided ropes with cores not made of cotton, as well as many ropes sold in hardware stores and/or variety stores, unless they are of the type previously specified as being likely to wash well. (Note: Unsuitability for washing often becomes much more than obvious the first time that the rope is washed. Be sure to use a lingerie bag.)

A few supplemental washing instructions:

• Blood can stain some types of materials if exposed to hot water. Therefore, washing away blood with cold water is advisable. Also, blood cells exposed to water of any temperature for more than about a minute can swell up, burst, and also stain the surrounding material with their cellular contents. Therefore, when removing blood from your ropes, hold them under cool, flowing water (the cold water coming from your bathroom or kitchen sink should work just fine) until the blood is washed off, then launder as usual.

• Most rope manufacturers recommend against using bleach when washing ropes.

Fabric softener can be used as an adjunct to your washing to make your ropes softer. Your local supermarket or variety store may even sell a roughly baseball-sized ball that can make doing this easier. Just be sure to not use too much.

Note: I found that ropes which had been washed in ordinary detergent (without using fabric softener) a few times often became just as soft as rope that had been washed with fabric softener. Thus, unless you are already routinely using fabric softener in your laundry anyway, you might find it just as easy to simply run your ropes through a few more washings.

I also found that some types of sealants used on the ends of ropes, such a liquid rope whipping, did not stand up well to repeated washings with both detergent and fabric softener, but did stand up well to repeated washings with detergent alone.

• I should note in passing that washing your ropes in a standard washing machine along with the rest of your clothes does subject the ropes to a significant amount of stress and wear. Thus, while you should wash your ropes “as necessary,” it is probably not necessary to wash them after every usage. You should probably wash your ropes if you have good reason to believe that they might have become stained with something like semen, blood, or vaginal fluid. You should also wash your ropes before using them on a second person (especially if you have reason to believe that they might have the first person’s body fluids on them).

Stronger disinfection methods. What if I think I have significant reason to wonder if my ropes do have an infectious substance on them?

This is an interesting topic. As of this writing, I know of no cases in which it has been seriously alleged that a disease has been transmitted from one person to another by contact with a contaminated rope. Still, the possibility is there, so let’s consider how one might go beyond the ordinary cleaning of a rope to disinfecting it.

Here is a very important aspect of infectious disease to remember: In order to get any infectious disease from a bacteria, virus, fungus, etc. (herein after referred to as “the bugs”), one must first be exposed to what’s called an “infectious concentration” of the bugs. It most definitely does not take just one bug. Actually, it often takes several million of them.

Therefore, we don’t usually don’t have to sterilize our bondage gear (sterilize meaning to remove all forms of life on it). Rather, simply disinfecting it (disinfecting meaning to reduce the number of bugs down below the “infectious concentration” level) will usually do just fine.

There are two basic ways to disinfect a rope (or anything else): physical removal of the bugs or chemical inactivation of the bugs.

The usefulness of the physical removal option is often under-appreciated. For example, a good hand washing (fifteen seconds of vigorous lathering, followed by fifteen seconds of rinsing) can eliminate as much as 97% of all the bacteria on one’s hands. Your ropes can benefit from a similar treatment. Certainly running your ropes through a cycle in your washing machine will physically remove a lot of bugs. (Exposure to the detergent will not make the bugs happier either.)

Let me be candid here: While you are certainly free to take further steps if you wish, as of this writing I know of no cases in which it has been seriously alleged that a disease was transmitted by a rope that got contaminated with infectious materials from one person on it but was run through a standard washing by a standard washing machine (even if cold water and a very mild detergent was used) before the rope was used on another person.

Realistically, the “washing machine option” seems to offer us a very great deal of protection in this regard. In almost all cases, the level of protection provided is probably much more than adequate. This is particularly true if such washing is combined with allowing the ropes to dry thoroughly afterwards. (See below.)

Also, let us consider that, most of the time, rope is applied to unbroken skin, and unbroken skin is resistant to many bugs. Exceptions, of course, would apply to ropes applied directly to the mucous membranes of the vulva, ropes used as gag straps that go into the mouth and thus come into contact with saliva, and ropes applied to skin that has had welts or other breaks caused in it by abrasions SM play. Also, skin that is initially unbroken sometimes becomes broken by the ropes themselves. Still, it’s my experience that most rope is applied to unbroken skin and removed from unbroken skin.

If you want to go further, you can consider these additional steps.

Many bugs need a moist environment to survive, so simply allowing your ropes to dry out for several hours (as in, say, overnight) will kill large numbers of them.

(Note: most of the disinfecting methods I describe here will kill just about all bugs except for a very few special bacteria that have already formed a hard outer coat called a spore. Spores can survive many harsh treatments, including exposure to boiling water. However, about the only “spore former” that we need to worry about, at least in an SM context, is the bug that causes tetanus. Um, your tetanus shot is up to date, right?)

Many bugs cannot survive more than a few seconds of exposure to the ultra-violet light contained within sunlight. (Most bacteria in soil are found down in the soil, away from sunlight.) Therefore, exposing your ropes and other toys to direct sunlight (not sunlight that has passed through glass, plastic, etc., but direct sunlight) for several minutes will deactivate many types of bugs. Please note that sunlight does not penetrate well, so for the bugs to get zapped they will need direct exposure to the sunlight.

If you want to go further, you can:

• Soak your ropes in a solution of one part chlorine bleach to nine parts of water for twenty minutes. This will kill virtually everything. Please note that many rope manufacturers recommend against exposing their ropes to chlorine bleaches on the grounds that the chemical effects of such bleaches will weaken the ropes. Please also note that chlorine bleaches may decolorize some ropes.

• Soak your ropes in a solution of 70% isopropyl alcohol or ethyl alcohol for a few minutes. Most of the bug killing will be done by the end of the first minute that the rope is in this solution.

• Boil your ropes. Prolonged boiling is not necessary. By the time the water starts to boil, you can safely bet that every bug that can be killed by boiling (all but the spore-formers which have already formed their spores, and a few bugs from fecal material which are unlikely to cause problems) has been killed by then. Warning: Ropes made of synthetic materials may melt if exposed to boiling water.

Note: It’s now possible to be immunized against both Hepatitis A and Hepatitis B. The first is a two-shot series and the second is a three-shot series, both given over a roughly six-month period; my medical consultant tells me that the two immunizations will soon be available in a combination injection. I recommend that all SM players (and virtually everybody else) get immunized against these very serious diseases.

Drying your ropes. Ropes made entirely of natural fibers, such as pure cotton rope or sisal rope, can usually be dried in your clothes dryer along with the rest of your clothing. (Be sure to keep them in the lingerie bag.)

On the other hand, ropes made of synthetic materials, such as nylon, polyester, and polypropylene, should probably not be placed in the dryer (unless, maybe, you turn your dryer’s heat down to a very low level). This is because the heat generated by such a dryer at its typical “dry ordinary wet clothing” setting can cause ropes made of synthetic materials to melt, filling your dryer with an icky plastic-like goo that could be very difficult to remove.

Simply letting such ropes air-dry should work fine. I’ve found that ropes made of synthetic materials frequently come out of the washing machine feeling almost dry already, so a relatively short amount of air-drying time is often sufficient. (Please also remember that a significant period of drying, such as overnight, can be a fairly effective disinfectant.)

Given their relatively high surface-to-volume ratio, most ropes tend to dry fairly quickly. However I have found that ropes made of natural material, such as cotton or sisal, take noticeably longer to air-dry than do ropes made of synthetic materials. I also note that ropes made of nylon tubular webbing seem to take longer to air-dry than do more conventionally shaped nylon ropes.

STORING YOUR ROPES

Once you’re done preparing your ropes, you’ll want to store them until it’s time to use them. As always, there are a number of ways to do this.

First, it’s probably not a great idea to simply dump a tangled mass of ropes into the drawer of your nightstand table, dresser drawer, or toy bag, thus creating what many folks call a “rope salad.”

It can be a subtle warning flag when an SM person, particularly a dominant, dumps out a ragged assortment of toys, including a mass of tangled ropes, just prior to playing. It can indicate sloppiness, carelessness, or cluelessness – none of which are good qualities in a potential play partner, particularly one to whom you’re considering making yourself very vulnerable. On the other hand, the sight of a clean, well-organized toy collection can be reassuring. It can also be, in its own way, deliciously scary.

It generally works well to separate out each piece of rope and then coil or otherwise organize it for storage and ease of use.

By the way, I recommend that you wait until a rope is completely dry after being washed before coiling or storing it. Rope, especially rope made of natural materials, that is put away damp, particularly if put away into a dark place where there is poor air circulation, can become a good “growth plate” for bacteria, mold, etc. Do not underestimate the value of keeping your ropes dry as a means of keeping them free of bugs that can transmit disease. This applies to your other SM gear as well.

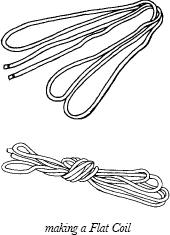

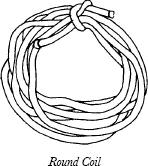

There are a number of ways to coil and store rope, including what I call the Flat Coil, the Round Coil, the Bighted Round Coil, the Figure-8 Coil, and the Hanging Coil.

In general, for routine storage of ropes in dresser drawers, toy bags, and so forth, the Flat Coil, the Round Coil, and the Bighted Round Coil all work well. They can also work well for hanging ropes on hooks, pegs, and so forth.

The Flat Coil. A flat coil is very quick, easy, and simple to make. In my opinion the Flat Coil is the most generally overall useful way of storing bondage ropes. By the way, I call it the Flat Coil because rope that is stored in this manner shows more of a tendency to “lay flat” than rope stored in a Round Coil.

As I said, a Flat Coil is very easy to make. Simply fold your rope in half (this is also called “bighting the rope”), then fold those halves in half, and repeat until the rope becomes difficult to fold further. A six-foot rope will typically take about two such folds, while ropes in the twelve-foot to 24-foot range will typically take about three such folds. Once you have reached this point (at which time ropes in the twelve-foot to 24-foot range will be folded to eight “widths” in thickness), tie the entire coil into an overhand knot, and you’re done.

A 50-foot rope will typically take about four such coils and be 16 “widths” in thickness. This amount of width can make creating the final overhand knot something of a challenge, but it can be done. A 100-foot rope will typically take about five such coils and be 32 “widths” in thickness. Making the final overhand knot in this case can even more challenging, but possible with practice.

A refinement: If you want to make the ropes a bit easier to store and to handle while they are coiled in a Flat Coil, tie the overhand knot out towards one end as opposed to near the middle.

Another refinement. If you are folding a somewhat long rope – say, 24 feet or longer – you may find that rope storage is easier if you tie an overhand knot near both ends of the folded rope.

The Round Coil. A Round Coil is also easy to make and can work very well for either six-foot or twelve-foot lengths of rope. I’ve also found that it can work acceptably, if not optimally, for lengths of rope up to about 25 feet long.

It’s very quick and simple to make a Round Coil. If you’re right handed, place one end of the rope in your left palm with its tip at the little-finger edge Then simply wind the coil in a clockwise direction (as you look down at your fingertips) around your left palm and fingers until you have about six inches of rope left, then run the final end over the left hand side of the coil, bring it back through the coil, and tie it into an overhand knot.

If you are using a very long rope (say, 24 feet or longer, you can simply wind the rope around your upper arm instead of your palm.

The Bighted Round Coil. A very simple variant on the above technique is to simply bight the rope, then wind it into a round coil as described above, starting with the tails and finishing with the bight. One interesting feature of this technique is that it leaves a small loop in the end, which can be hung on a hook.

The Figure-eight Coil. The Figure-eight Coil tends to work well for ropes that are at least twelve feet long. (Shorter ropes don’t easily stay in the figure-eight configuration.) One of the major benefits of storing braided rope in any variant of the Figure-eight coil is that doing so greatly reduces or eliminates “the twists” in rope. More on this later.

“Look at how much more flexible this rope is after you’ve removed the core.”

To store your rope in a Figure-eight coil (assuming that you’re right-handed), grasp the tip of the rope in question in your left hand with its tip just slightly protruding from your fist. Now flex your elbow joint into the “make a muscle” position. (How much you must flex your elbow joint will depend on a number of factors, including your size and the length of the rope. How much flex is needed will be discovered with practice.) Wind the rope in a figure-eight pattern over your outer forearm, then around your elbow, back over your forearm, and through your left palm. Continue until you run out of rope, knot the tail around the strands on the palm side of your rope as you would if making a Round Coil, and you’re done.

As a minor variant, if you have a bit too much rope left over, bend the surplus back into a bight and use that bight to make your final knot.

The Bighted Figure-eight Coil. This is a simple variant on the standard Figure-eight Coil, and tends to work best in ropes that are at least 18 feet long. It is a simple coil to create once you’ve learned how to make a regular Figure-eight Coil. Simply bight the rope and proceed as above.

The Hanging Coil. If you want to store a coil of your rope by hanging it on a peg, hook, or bedpost, you can create what can be called logically be called a “hanging coil” of rope. As always, there are a number of different ways to do this. The various books on knots in the Bibliography describe a myriad of techniques.

One very useful and relatively simple method of tying a hanging coil is to loop the rope as you would for a Round Coil, but make the loops at least twice as big. (The longer the rope, the larger you should make these coils. When you get to the end, fold the tip of the tail back over the coil to create a bight. Then wrap this bight of rope around the coils and run it under itself to create an overhand knot, like you did for the Bighted Round Coil. Finally, bring the bight back over the top portion of the coil, wrap it under the coils, and tuck it under itself to create a handy loop for hanging the finished coil.

The Bighted Hanging Coil. Another method of forming a hanging coil that is especially useful for bondage purposes is to bight the rope, then wind this bighted rope into coils, starting with the tails. Create the final finishing loop in the same way that you did for the Hanging Coil.

This technique creates a very tidy-looking hanging coil that can be quickly employed for bondage purposes. To use it, simply remove it from its peg, take out the midpoint, stretch out the ropes through your fingers to remove the twists, and you’re ready to deal with the twists in your rope.

Storing Ropes on Hooks, Pegs, Bedposts, etc. Bondage fans some-times want to store their ropes in a place where the ropes are readily visible and ready to use. This can be fun, but must be approached with some caution. For on thing, if one’s relatively “vanilla” friends, business acquaintances, landlords, and so forth go into one’s bedroom, the sight of all those ropes may bring on unwanted attention. For another thing, having all those ropes in plain sight may scare people who are new to the idea of bondage. While keeping ropes stored in a visible and ready-to-go condition may work well in a formal SM playroom such as the “dungeons” used by professional dominatrixes, it would be wise to think twice before setting up one’s bedroom in this way.

Shorteropes, such as six-foot and twelve-foot ropes, can often be stored quite nicely by simply ahnging them in Lark’s Head knots (see p. 139) from the bed railings.

If you want to get even more blatant about it, you can hang a towel rack by your bed and put your ropes up on that. One friend of mine went to a boating supply store and bought what’s called a “line hanger” to use. This line hanger very neatly holds four coils of rope ready for use. (Of course, my friend, being the discreet type, put up his line hanger inside his closet, thus keeping his gear stored in a more low-profile manner.)

Finally, while there are a number of “formal” techniques for folding a rope so that it can be hung on a peg, keep in mind that the Flat Coil, the Round Coil, and the Bighted Round Coil can often work just fine for this purpose.

Dealing with the twists. Many methods of coiling a rope for storage, particularly storage techniques such as the Round Coil, also impart some twists to the rope. You can see these when you uncoil the rope. For example, hold a six-foot rope up off the ground by one end and you may see the other end spin as it untwists itself. It may even form loops.

Twists can be a nuisance in the erotic bondage context. For longer ropes (fifty feet or more) they can be distinctly irksome. In more serious real-world usages, such as rescue work, twists can create life-threatening problems.

There are several strategies for dealing with twists. The first strategy is to simply live with them. As I said, in erotic bondage, twists typically aren’t all that great a problem, particularly with the shorter ropes that we generally use, and you can simply let the rope uncoil naturally.

A second strategy, my personal favorite, is to “milk out” the twists just before you use the rope. This can work especially well for relatively short ropes in the six-foot to twelve-foot range. One good method of doing this is to uncoil the rope, hold it by the midpoint in one hand while you “milk out the twists” in the two parts of the rope with the other hand – one part going between your thumb and index finger and the other part going between your index and middle fingers. This can sometimes be done with a wicked “domly” flourish – just be careful to not get too melodramatic.

A third strategy is to coil your braided ropes in Figure-eight Coils. These have been described above and often work very well indeed.

A fourth strategy is what can be thought of as “counter-twisting.” To do this, give each coil of the rope a half-twist in the counter-clockwise direction as you use your right hand to coil it into clockwise loops onto your left hand – as is done in creating the Round Coil. It seems easiest to give the rope this twist at the top of each coil. Practice this with a six-foot length of rope and you should pick it up easily enough.

To see if you added counter-twists properly, coil the six-foot rope, then hold it up slightly over your head by one end and drop the coil. An inadequately counter-twisted rope will have loops appear in it as it falls and/or its free end will spin. You may even have to shake the rope a bit to get it to entirely untwist. An adequately counter-twisted rope will fall pretty much straight down, with little or no looping or spinning.

To test this with longer ropes, try holding one end and either dropping the other end down something like a stairwell or throwing it “lifeguard-style” down a hallway. An inadequately counter-twisted rope will come up short in a tangled heap. An adequately counter-twisted rope will play out much more freely.