Chapter 12

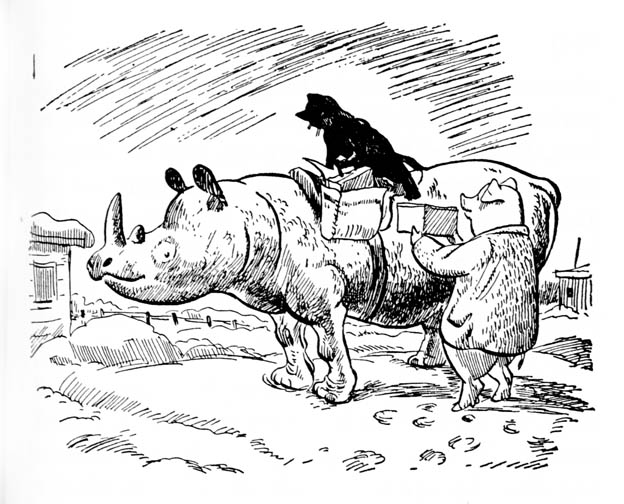

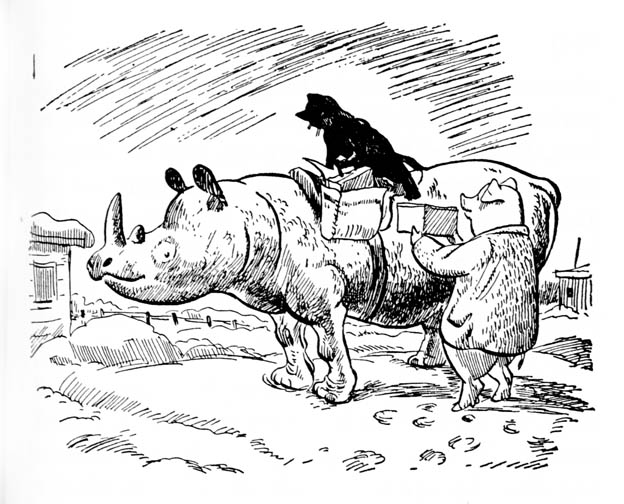

The animals had a pretty uneventful trip south. They were seen and followed once or twice by hunters, but now that the snow was gone it was easy enough to throw any pursuers off the track. Jinx had decided to come along. He had got so interested in painting that he hated to leave his studio, but as he said, he had the rest of his life to paint in, while a chance to have all sorts of adventures in good company didn’t come very often. He ended by taking his paints along, packed with a double rule of molasses cookies Mrs. Bean had baked for them, and the rest of their baggage in the saddlebags attached to Jerry’s saddle. Mrs. Bean had made the saddlebags out of an old blanket. Jerry was very proud of the saddle the prisoners at the jail had made for him, and wore it even when he went to bed.

Jinx didn’t have any chance to paint on the road, for there was a lot to see and they traveled steadily. They sang a good deal—the old marching song that the Bean animals had sung on the trip to Florida, and the Boomschmidt marching song, and the campaign song Freddy had written when Mrs. Wiggins had been a candidate for the presidency of the First Animal Republic. Freddy didn’t have time to compose new songs, but he did make up some verses to the tune of Froggy Went a-Courting. They were about Edward, and they went like this:

Edward went a-Courting, he did waddle, h’m—h’m.

Edward went a’courting, he did waddle

Through the brook and over the puddle, h’m—h’m; quack—quack.

He came to Lady Alice’s hall, h’m—h’m.

He came to Lady Emma’s hall

And his feet were so cold he could hardly crawl, h’m—h’m; quack—quack.

He took Lady Alice on his knee, h’m—h’m.

He took Lady Emma on his other knee,

And he said: “Will the both of you marry me?” quack—quack; quack—quack.

Lady Alice giggled and shook her head, tee—hee.

Lady Emma tittered, and they both said:

“We’ll ask Uncle Wesley if we can wed,” tee—hee; quack—quack.

Uncle Wesley came and he said: “No, no!” h’m—h’m.

Uncle Wesley growled and he said: “No, no!”

But they pushed Uncle Wesley out in the snow, quack—quack; no—no.

Where shall the wedding supper be? h’m—h’m.

Where shall the wedding supper be?

Down in the barnyard under the tree, h’m—h’m; h’m—h’m.

The first that came was Jinx, the cat, meouw—meouw.

The first that came was Jinx the cat,

He wore high boots and a big plug hat, h’m—h’m; meouw—meouw.

The next that came was Leo, the lion, woof—woof.

The next that came was Leo, the lion,

With his claws manicured and his mane a-flyin’, h’m—h’m; woof—woof.

The next that came was the rhinocer-us, umph—umph.

The next that came was the rhinocer-us,

And he ate so much that he almost bust, h’m—h’m; umph—umph.

The next that came was Freddy, the pig, oink—oink.

The next that came was Freddy, the pig,

And with the bridegroom danced a jig, oink—oink; quack—quack.

The last that came was old Witherspoon, O dear!

With an axe in his hand came old Witherspoon

And chopped off his head by the light of the moon, O dear! h’m—h’m.

And that was the end of the bashful duck, h’m—h’m.

And that was the end of the bashful duck;

To end on a platter was just his luck, quack—quack; h’m—h’m.

This made a good song, because they could change it every time they sang it and make up new verses. Even Jerry made up one, and it wasn’t a bad one either, about the next that came being the rhino, Jerry, whose home was on the wide, wide prairie. And when one of them had made a new verse, they’d all sing it as a quartet. Freddy carried the air, and Jinx sang a kind of wailing tenor, and Leo sang bass, and I don’t know what you’d call what Jerry did. He had a grunt that was as deep as a bull fiddle, and when he hit the right note it sounded real nice.

It grew warmer as they traveled southward, and pretty soon they met the spring, which was traveling northward, and the grass was green and the trees in bud, and there was arbutus in the woods and thousands of birds, traveling up with the spring. They would have liked to ask the birds for news of any of the other circus animals that they might have seen, but the birds were much too anxious to get home and start repairing the damage that winter storms had done to their old nests to bother answering questions.

Early that afternoon they came down through some pine woods on to a hillside overlooking a wide, shallow valley. Down in the valley a racetrack was laid out, at one side of which was a grandstand, and flags were flying from the grandstand, into which crowds of people were pouring. Blanketed horses were being led around in an enclosure near the track and it was plain that there was going to be a race.

Everybody likes to see a race, so when Jinx suggested that they sneak down along the fence and get up close to the track on the east side where there was a little clump of trees, they started down. There was so much going on around the track that they reached the trees without attracting attention, and while they were waiting for the race to begin they decided to have lunch. Freddy had just started on his second cookie when a creaky voice said: “Y’all got anything to eat?”

The heads of the four animals jerked up as if they had been pulled by a string, and they saw a large buzzard sitting on a limb above them. His plumage was as rusty as his voice, and one round greedy eye was fixed on the open cookie box.

“Thank you, yes; we have plenty,” said Freddy with a grin.

“I ain’t askin’ if y’all got enough,” said the buzzard. “I’m askin’, could you spare a bite?”

“Oh, go away,” said Jinx. “We haven’t got anything you’d like anyway; we know what buzzards eat—just garbage.”

“We prefer to call it left-overs,” said the buzzard, looking reproachfully at the cat. “Buzzards, mister,” he went on, “just clean up after untidy folks, like it might be you all, leavin’ crumbs and banana skins all over nice clean landscapes.”

“Well, there won’t be any left-overs here, or any garbage either,” said Jinx, “so you might as well beat it.”

“Wait a minute,” said Freddy. “You—what’s your name?”

“Phil,” said the buzzard.

“Well, Phil, if you can help us, we’ll give you one of our cookies. We’re looking for some animals that used to be with a circus, and maybe you’ve seen some of them.” And he explained about Mr. Boomschmidt’s animals.

But Phil shook his head. “They sound like right pretty animals,” he said, “but in these yere woods there’s only coons and foxes and squirrels and a few deer and possums. Tell you what there is, though,” he said; “there’s a big old snake lives down in the swamp t’other side the racetrack. He’s twenty, twenty-five feet long, I reckon, and he’s kind of a curiosity around these parts. He’s—”

“Well, clip my whiskers!” interrupted Leo. “I wonder if that’s Willy. Remember Willy, Freddy—our boa constrictor? What color is he, Phil? How’s he marked?”

“Mister,” said the buzzard, “he can be pink with yellow stripes and a long green moustache for all I know or care. I don’t go round measurin’ no snakes.”

“We’ll have to go down there,” said Jinx. “Well, Phil, here’s your pay.” And he tossed him a cookie.

Leo watched the buzzard as he smacked his beak over the cookie. “You must be from the south, Phil, from your talk.”

“From the south! I ain’t from the south, Yankee; I’m at the south. Virginia’s my home.”

“Virginia!” Freddy exclaimed. “You mean we’re in Virginia already?”

Phil assured them that they were, and a little questioning brought out the fact that they were within ten miles of Yare’s Corners, which was just over the mountain from the Boomschmidt place. They were discussing whether to push on at once, or to watch a race or two first, when two of the track officials came riding in among the trees. They had caught sight of the animals through their field glasses, and had come over to investigate.

“Jumping Moses, a lion!” said one.

“What is this—a menagerie?” said the other, who was a thin, middle-aged man with a wisp of grey whisker on his chin.

The first one said: “A lion and a pig and a cat and a—well, what is it, Henry—that creature there with a saddle on?”

“Good afternoon, gentlemen,” said Freddy politely. “May I present my friend? He’s a rhinoceros. Jerry, this is—ah—”

“Major Hornby,” said the first man, bowing. “And this is Mr. Bleech, Henry Bleech. Are you … I see this saddle on—on Jerry,—are you planning to enter the third race?”

“No,” said Freddy. “No, we were just watching—”

“We ought to have him, Major,” said Mr. Bleech eagerly. “He’d be a great drawing card, this rhin—whatever he is.” He turned to Freddy. “There’s a purse of two hundred dollars, and your Jerry here—he’d have a good chance to win. You see it’s a free for all, the third race. All the other races are for horses, but the third is for any animal except horses. But we’ve only three entries—a cow, a ram, and a camel. Is your Jerry fast?”

“A camel?” said Freddy. “Where’s he from?”

“Belongs to some crazy old fellow over beyond Yare’s Corners that used to run a circus,” said the Major. “See here, I don’t suppose you’ve got the money for the entry fee. It would cost you ten dollars to enter Jerry in the race. But I’ll gladly pay it out of my own pocket if—”

“We always pay our own way,” said Freddy coldly. The slighting reference to Mr. Boomschmidt had made him angry. “Excuse me.” He drew his friends aside and held a short consultation. Then he came back. “I think we’ll pay twenty dollars and enter both Jerry and Leo.”

“That lion?” said Mr. Bleech. “See here, Major, I don’t know that I want to ride my cow in a race with a lion. Suppose the lion forgot it was a race, and decided it was a chase? Eh? Suppose—”

“You need not worry, sir,” said Leo courteously. “I never chase cows. Personally it seems rather unsporting.”

“Leo will have to run without a rider,” said Freddy. “Jinx will ride Jerry, because there’ll have to be somebody to steer him, but nobody could ride a lion bareback. Is that all right?”

Major Hornby said it was and they all started down to the paddock. On the way, Freddy fished in the saddlebags and brought out a twenty dollar bill, which he handed to the Major. He didn’t like the way Mr. Bleech eyed him when he was doing this, and when he had a chance he whispered to his friends that they’d better leave the saddlebags on during the race. A few extra pounds would make no difference to Jerry, and their money would be safe.

The Major explained that this free for all race was a very popular feature of the local race meets, and many people who didn’t care much about horse racing would come for miles to see Mr. Bleech’s cow, Galloping Nellie, run against Stonewall Jackson, the Major’s racing ram, who were pretty evenly matched. Many more had come this time because of the camel. “And I wish we’d known beforehand that we’d have a lion and a rhinoceros,” said the Major, “so we could have advertised everywhere. Why I daresay there are people who would come fifty miles to see a race like that.”

So great, indeed, was the interest in the new entries, that most of the spectators crowded down into the paddock, and the first two races were run with only a handful of onlookers in the grandstand. The camel was in the paddock, too. He was a supercilious, ill-natured beast named Mohammed. When he saw Leo and Jerry, he gave a start of surprise, then turned his head away. But Bill Wonks, who was leading him, shouted and waved, and started to push through the crowd towards his old friends, when the third race was announced. “See you later,” Bill called, then whacked Mohammed on the shins to make him kneel, so that he could get on his back.

The crowd dashed for their seats, and as Jinx leaped into the saddle and Jerry and Leo filed out after the camel on to the track, Freddy joined Major Hornby in his box in the front of the grandstand. Through the Major’s field glasses he looked at the contestants as they lined up at the start.

“That’s my son, Forrest, on Stonewall,” said the Major, pointing to a boy of ten or eleven who was mounted on the ram. “Broke and trained Stonewall himself, and don’t think that ram can’t run. Trouble is, he hasn’t any sense of direction—he ran the whole race in the wrong direction around the track last fall. He and Nellie met at the finish line, but Stonewall crossed it first. Of course the judges decided for Nellie, because she’d gone the right way. Didn’t seem quite fair to me. It’s the same distance either way.”

“That’s Jerry’s trouble too,” said Freddy. “No sense of direction. Or rather, he thinks there’s only one direction—straight ahead. Only way we could figure out to steer him was to hold something out on a stick in front of his nose, and turn it whichever way you want to go. That’s why Jinx has got that stick.”

This was something Jinx and Freddy had figured out before the race. They knew that as soon as Jerry started to run he would shut his eyes and dash off in a straight line, which isn’t much good on a circular track. But he had a keen sense of smell, and could follow a cookie dangled on a string in front of his nose. At least they thought he could, and Jerry agreed with them.

“I’m backing Stonewall to win, of course,” said the Major. “Which one do you fancy, Mr.—ah—”

“Just call me Freddy,” said the pig. “Well, I only know about my own entries, but I’d back Jerry. Lions get off to a quick start, but they sort of slow down after a minute, while a rhinoceros keeps building up his speed the longer he runs.”

“What do you think of the camel?”

“He can run to beat the band,” said Freddy. “But camels are contrary. Nothing makes them happier than disappointing somebody. If this camel thought his rider wanted to lose the race, he’d tear in ahead of everybody. My guess is, he’ll come in last.”

“You seem to know a lot about racing,” said the Major, looking at Freddy with respect.

“I know a lot about animals, probably because I’m one myself. Oh, there goes the gun!”

There was a bang from the starter’s pistol, and the animals were off. Leo took the lead, but the others came up quickly on either side and passed him. Freddy hadn’t thought much of Galloping Nellie. Cows aren’t built for speed, and don’t usually care much for it. But this cow was lean and rangy, and she stretched out her neck and held her tail straight up in the air, and with Mr. Bleech crouched on her back, skimmed over the ground like a racehorse. She had the inside position, next the rail, and at the quarter she was well out ahead. “Golly!” Freddy said to himself. “I wish Mrs. Wiggins could see this!”

It was a pretty exciting race. The people in the grandstand went wild. They stood on the seats and yelled and waved their hats and pounded one another on the back, and several people fell off their benches and got bruised, but they got right up again and didn’t even feel it. The Major screamed: “Come on, Stonewall!” until he turned purple and lost his voice, but he kept right on opening his mouth, though no sound came out. At the halfway post, Nellie was still ahead. On her right the camel was swinging along at a smooth trot, but obviously not half trying, in spite of the way Bill was whacking her with his stick, while on his right Stonewall was coming up fast. Leo had dropped back and wasn’t trying any more either. He was shaking his mane self-consciously, and Freddy knew that he was thinking that if he couldn’t win, he could at least be admired for his good looks. On the outside, Jerry was only a little ahead of Leo, but he was beginning to pick up more speed, and Freddy was pleased to see that he was following the cookie very exactly. At the turns, Jinx would swing the cookie a little to the left, and Jerry would follow around the curve as smoothly as if he was running on rails.

Gradually Stonewall and Jerry began to catch up with Nellie. When they came into the stretch, the three were running almost neck and neck. The crowd screamed and yelled louder than ever, and several people fell right out of the stand. An elderly uncle of the Major’s had his hat smashed down over his eyes so tight that he couldn’t pull it off without help, and as nobody would help him, he never saw the last part of the race at all. Mr. Bleech was sitting far forward on the cow’s neck and whacking her with the whip as if he was beating a carpet in the effort to maintain his lead, which was now less than a foot. But both Stonewall and Jerry came up and forged ahead and bore down side by side on the finish line.

Freddy was up on his chair now, yelling like the rest of them. “Jerry! Come on!” Of course Jerry couldn’t hear him. But he came on just the same. He came on like a steam engine, snorting with every bound, and the horn on his nose crept up past the heavy curved ram’s horns, hung there a minute, and, fifty yards from the finish line, went on ahead.

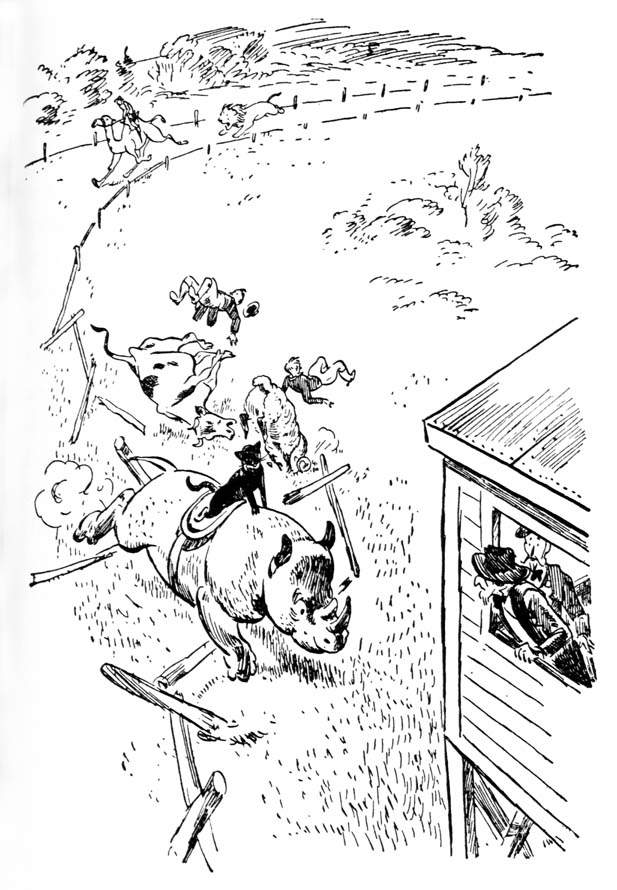

And then it happened. A cookie hasn’t any waist to tie a string around, and so when Jinx had fixed up Jerry’s steering gear, he had punched a hole in the cookie and tied the string through the hole. But the string had gradually sawed through the cookie, which all at once broke in two and dropped to the ground. Suddenly the spicy cookie smell, which Jerry had been following, wasn’t there any more. He swerved and brushed against Stonewall, and although he didn’t hit him hard, the ram shot sideways through the fence as if he had been side-swiped by an interstate bus. In doing this, Stonewall clipped Nellie, who turned a complete somersault. Mr. Bleech flew in the air and landed flat on his face, just as Nellie came down and landed in a sitting position on top of him, so that their positions were exactly reversed. And Jinx gave a yell and jumped off.

And then Jerry swung still more to the left and instead of crossing the finish line he charged full tilt into the judges’ stand, which was built up close to the side of the track. There was a terrific crash as the stand seemed to explode, and the air was full of planks and shingles and judges and pieces of two-by-four. And when the dust settled, the people in the stand saw the judges sitting, very grimy and confused, on the heap of rubbish that had been the stand, while the rhinoceros charged on across the turf inside the track, smacked through the fence on the other side, and disappeared among the trees.

He charged full tilt into the judges’ stand.