Chapter 16

They clattered down the stairs, shouting and laughing, but when they got back to the porch Mr. Boomschmidt called for quiet. “There’s just one thing,” he said. “This money belonged to Col. Yancey. See?—it says on the paper: Property of Col. Jefferson Bird Yancey. Now Col. Yancey is dead, and I understand he left no living relatives. So who does this money really belong to? Does it really belong to us?”

“If the house belongs to you, the money you found in it belongs to you,” said Jinx, and the others agreed.

“Yes,” said Mr. Boomschmidt. “Yes, I suppose so. I just want to be sure.”

“Never look a gift horse in the mouth, chief,” said Leo.

“Horse?” Mr. Boomschmidt screwed up his face in puzzlement. “What are you getting at, Leo? There’s no horse here. Lions, boas, pigs, cats—no horse. I’m afraid you’re a little over excited, Leo; perhaps you’d better go in and lie down on the couch for a while.”

“You know what I mean,” said the lion. “I just mean, if you get a present, it isn’t nice to ask many questions about it.”

“A present?” said Mr. Boomschmidt, looking questioningly at Leo. “A present from whom?”

“Well,” said Leo, looking embarrassed, “I guess it’s a present from Col. Yancey, isn’t it?”

“Oh,” said Mr. Boomschmidt. “Oh, Col. Yancey. Yes.” He began counting the money. “Fifteen hundred … sixteen hundred … seventeen hundred—Funny! It’s almost exactly the same amount that—excuse me mentioning it, Freddy—but it’s almost exactly what that man stole from you.”

“Why—is it?” said Freddy nervously. “Yes, of course it is. Odd, eh?”

“Just a coincidence, chief,” said Leo, trying to make up for his slip of a minute earlier.

“Life is full of coincidences like that,” said Freddy. “I remember one time—”

“Excuse me, Freddy,” said Mr. Boomschmidt, “but my gracious! we haven’t time for reminiscences today. We’ve got to get organized. Got to get the tents and wagons out and look them over, got to get new crews together.… Bill, you have the addresses of most of the old employes, haven’t you? Well, send ’em all telegrams: ‘Come at once; circus reopening immediately.’ Leo, you and I will see how many of the animals we can round up. Gracious, that’s a big job! Got any ideas about it, Freddy?”

Freddy told him how he had found where Leo was, by showing the birds a picture of a lion.

“Splendid!” said Mr. Boomschmidt. “Isn’t that a splendid idea, Leo? I knew we could count on you, Freddy. And by the way, how about coming in as my partner? The offer still stands. We need you; eh, Leo?”

“Sure do, chief.”

Freddy shook his head. “A partner has to bring something to the partnership,” he said. “I was to bring the money, and you, the know-how and equipment, remember? But I lost the money—”

“You raised it, didn’t you?” said Mr. Boomschmidt. “ ’Tisn’t your fault you lost it. Now don’t say no. You don’t want to hurt my feelings, do you?”

Freddy said of course not.

“Well, my feelings hurt awful easy,” said Mr. Boomschmidt. “You just ask Leo if they don’t.”

“That’s right, Freddy,” said the lion. “The chief’s awful sensitive. Why, I’ve known him to cry half the night, just when one of the snakes forgot to come in and say goodnight to him. Heard him myself in his bedroom, sobbin’ and moanin’ and—”

“There, there; that’s enough, Leo,” said Mr. Boomschmidt. “No need to overdo it. Well, Freddy, what do you say?”

“I guess I ought to tell you,” said the pig. “I didn’t really want to be a partner in the show. Oh, I know it would be fun, and I’d enjoy being with you and all the animals, and on the road and everything. But it would keep me away from the farm all summer. And I wouldn’t like that.”

“I see,” said Mr. Boomschmidt. “Yes, yes; should have thought of that myself. Well, that settles it, then. But I tell you what I’m going to do. I’m going to make you a sort of partner just the same. When Boomschmidt’s Colossal and Umparalleled Circus goes on the road, it’s going to be—not just Boomschmidt’s, but Boomschmidt & Company’s. And you’re going to be the Company—or abbreviated: Co. Not that we’d want to abbreviate you, Freddy; on the contrary. Anyway, I wouldn’t know how to abbreviate a pig, even if I wanted to.”

And then as Freddy started to protest: “Now, now,” he said. “What was it Leo said? Leo, what … Oh, I remember: mustn’t look a gift horse in the mouth. Seem to be several gift horses prancing around here this morning. Well, let’s keep their mouths shut, eh, Freddy?”

Freddy didn’t say anything for a minute, but he thought: “I bet he knows! He knows that’s my money.”

Then he looked at his friend and smiled. “Well,” he said, “I suppose one good gift deserves another.”

“That’s the ticket!” said Mr. Boomschmidt. “I couldn’t have said it better myself. At least, I don’t think I could. By the way, that reminds me of a queer thing.” He pulled the big roll of bills out of his pocket. “You know, that Col. Yancey, he hid these bills away back in the sixties. But I just happened to glance at this top one, and it says ‘series of 1934.’ Now that’s a very funny thing. How do you account for it? Leo, what do you think?”

Freddy wasn’t used to handling bills much, and it had never occurred to him that they would have dates on them. Of course Col. Yancey couldn’t have hidden a nineteen-thirty-four bill back in the sixties. He said to himself: “So that’s what made him guess where the money came from!”

Mr. Boomschmidt was glancing from Freddy to Leo, waiting for an answer. He had a very puzzled look on his face, but whether it was real, or just put on for the occasion, nobody could tell. You never could, with Mr. Boomschmidt.

Freddy couldn’t think of a thing to say. But Leo said: “I expect those government printers—they were pretty careless in the old days—and they probably got a nine for an eight. Probably it was really the series of 1834.”

It was a pretty weak explanation, but it seemed to satisfy Mr. Boomschmidt. He stuffed the bills back into his pocket, and Freddy was glad to see them disappear, for he had looked at the top bill too, and there were a number of things on it that couldn’t possibly have been on a bill in 1860.

I don’t suppose Freddy was any more unobservant than anybody else. The most interesting thing about a bill is its value, naturally; and so the only thing most people look at is the number: one or two or five or ten. I don’t suppose you can tell offhand yourself whose picture is on the one dollar bill, or the five or ten either.

But although Freddy still wasn’t sure whether or not Mr. Boomschmidt knew about the money, he didn’t have time to worry about it. For Mr. Boomschmidt had got out his silk hat and put it on, and that meant that he was again a circus man; and he tore around the place, firing off orders like a machine gun, so that the plantation, which had been a quiet peaceful place when Freddy had got there, was turned into a regular factory, with people and animals running in all directions, and hammering, and sending telegrams, and overhauling gear, and doing the thousand things that had to be done to get the circus started again. Nobody even had time to think how funny the contrast was between Mr. Boomschmidt’s silk hat and his burlap suit.

For three days Freddy and Jinx worked at a big sign. It was a piece of canvas eight feet square, in the center of which were lettered these words:

BIRDS, ATTENTION!

A generous reward is offered for news of any of these animals. Have you seen any of them? Have you heard any unusual squeals, roars, squawks, howls or gibberings? If so, contact Mr. Boomschmidt at once. For any information you will be generously paid.

And then, all around the edge, they painted pictures of elephants, yaks, tigers, camels, zebras and all the other animals who had once been part of the circus. It wasn’t as hard a job as it seems. Jinx would get some animal about half painted, and then he would ask Freddy what it looked like. Maybe Jinx had started to paint a tiger, but if it looked more like a camel, he would say so, and then Jinx would make his legs a little longer, and give him a hump, and take off the stripes. Lots of artists would have much better pictures if they would work by this method.

Bill Wonks nailed the sign to the roof of one of the barns, and it wasn’t long before birds began dropping in with bits of information, a good deal of which was of value. Freddy posted Phil on the gable end of the barn, and he interviewed the visitors so intelligently that he was presently appointed Investigator in Charge of Bird Claims. On information received, he even made a number of trips, one of them as far as Tennessee, to bring in animals. By the end of the first week the circus had recovered four zebras, a gnu, a skunk, an aardvark, a family of monkeys and two alligators. The two elephants and the tiger who were living in the zoos in Washington and Louisville also came in.

The weather was getting warm now and one day Freddy, who had gone into Yare’s Corners to get a box of cookies which Mrs. Bean had shipped him, was sitting in the shade by the side of the road, cooling off, when two boys came along. The sound of their voices woke Freddy up, and he heard one of them say: “I don’t want zebras. But I’ll trade you my elephant for two giraffes.”

“Good gracious!” said Freddy to himself. He was still a little soggy with sleep, but he jumped up and ran out into the road.

“Excuse me,” he said, “but did I hear you correctly? Did I hear one of you offer to trade two giraffes for an elephant?”

“Sure,” said one of the boys. “He’s got an elephant I want, but I don’t see why I should have to give him two giraffes for him, do you? Giraffes are just as scarce as elephants.”

“Listen,” said Freddy. “There’s a reward for both elephants and giraffes—didn’t you know about it?”

“How much?” said one boy, and the other said: “Money?”

Freddy was still so sleepy that he couldn’t think very clearly, and he hesitated. It would be worth quite a lot to Mr. Boomschmidt to get these animals back, but these boys probably didn’t ever have much money. So he said: “A dollar apiece.”

He had expected that they would want a good deal more than that, but to his surprise their mouths fell open and they both said: “Gee whiz!” They were so astonished that they said it without closing their mouths.

Freddy was rather astonished too, but he thought he’d better close the bargain before they thought better of it. “Lead me to them,” he said, and fished three dollars out of his pocket.

But the boys didn’t lead him anywhere. They dug in their own pockets and brought out handfuls of animal crackers.

Then Freddy’s mouth fell open. “Oh, gosh!” he said, and he didn’t close his mouth when he said it either.

“What’s the matter?” they asked.

“Matter?” said Freddy, gasping a little. “Matter? Oh, nothing. Why, nothing at all.” He wasn’t going to let them know what a stupid mistake he had made. He held out the three dollars.

They sorted out the elephant and two giraffes and handed them to him in exchange for the money. And then Freddy did what I think was the only thing to do under the circumstances, and a pretty bright thing too. He put the two giraffes and the elephant in his mouth and chewed them and swallowed them, and then he smiled brightly and said: “Thank you very much. Good afternoon,” and walked off. And he had the satisfaction—although perhaps it wasn’t three dollars’ worth—of seeing their mouths fall wider open than ever. And they stayed that way, too, as they stood and watched him until he was out of sight.

So more and more animals came, and the men who had worked for Mr. Boomschmidt before gave up the jobs they had found and came too, for they all liked to work for him; and the tents were got out and put in shape, and the wagons were painted, and then one day along towards the first of June, Mr. Boomschmidt, in a brand new suit of red and yellow checks and with his silk hat on the back of his head, rode out of the gate into the road. He touched his trick horse, Rod, on the shoulder, and Rod stood on his hind legs and Mr. Boomschmidt waved his hat three times around his head and shouted: “Forward!” And then he rode on up the road, and one by one the gaily painted wagons creaked out through the gate and followed him, and as they rode, the animals sang a song that Freddy had made up for them.

We’re out on the winding road again,

The road where we belong;

By hill and valley, by meadow and stream,

On the road that’s never too long.

Never too long is the winding road,

Though it climbs the steepest hill

Though dark the night, and heavy the load,

When the rain drives hard and chill.

For the stormiest weather will always mend;

There’s a top to the highest hill;

But the winding road has never an end,

Whether for good or ill.

And we travel the road for the love of the road,

For love of the open sky,

For love of the smell of fields fresh mowed,

As we go tramping by.

For love of the little wandering breeze,

And the thunder’s deep bass song,

Which rattles the hills and shakes the trees

Like the roar of a giant’s gong.

For love of the sun, and love of the moon

And love of the lonely stars;

And the treetoads’ trill, and the blackbirds’ tune,

And the smell of Bill Wonks’ cigars.

And there, where the road curves out of sight,

Or surely, beyond that hill,

Adventure lies, and perhaps a fight,

And perhaps a dragon to kill.

Or perhaps it’s a brand new friend we’ll make,

Or a haunted house to visit,

Or a party with peach ice cream and cake,

Or something else exquisite.

So now for us all, for pigs and men,

For lions and tigers and bears,

The open road lies open again,

And we toss aside our cares,

And we sing and holler and shout Hurray!

No matter what the weather

For we’ll not be back for many a day

While we’re out on the road together.

They had gone only a mile or two, however, when Freddy saw Phil sitting on a fence by the side of the road. Buzzards are never very tidy looking birds at any time, but Phil looked worse than usual, as he raised a shaky claw to salute Freddy. The pig went up to him.

“For goodness’ sake, Phil,” he said, “what ails you? You look terrible!”

Of course that’s no way to greet anybody, even a buzzard who probably knows that he looks awful even when he feels all right. But Freddy was really quite shocked at the bird’s appearance.

“I feel right awful, Freddy,” the buzzard croaked.

“Want a cookie?” said Freddy. “We’ve got a couple in the—”

“Don’t,” moaned the buzzard despairingly. “I never want to see a—a—” He broke off. “I can’t even name ’em. It makes me sick to even hear the word.”

“Why, what’s the matter?”

“Well,” Phil said, “I reckon I sort of made a pig—oh, excuse me; I mean I made a hog …” He stopped and shook his head irritably. “You’ll have to excuse my bad manners,” he said apologetically. “I mean, I ate too many. I ate the whole double rule. I shore was sick! I like to have died; that’s why I ain’t been around this last month.”

Freddy was too concerned over Phil’s condition to be offended by the tactlessness of his remark about pigs. “You’d better see Mr. Boomschmidt,” he said. “He’ll know what to do for you; the circus animals are always eating too much of something or other, and he has to dose them for it.”

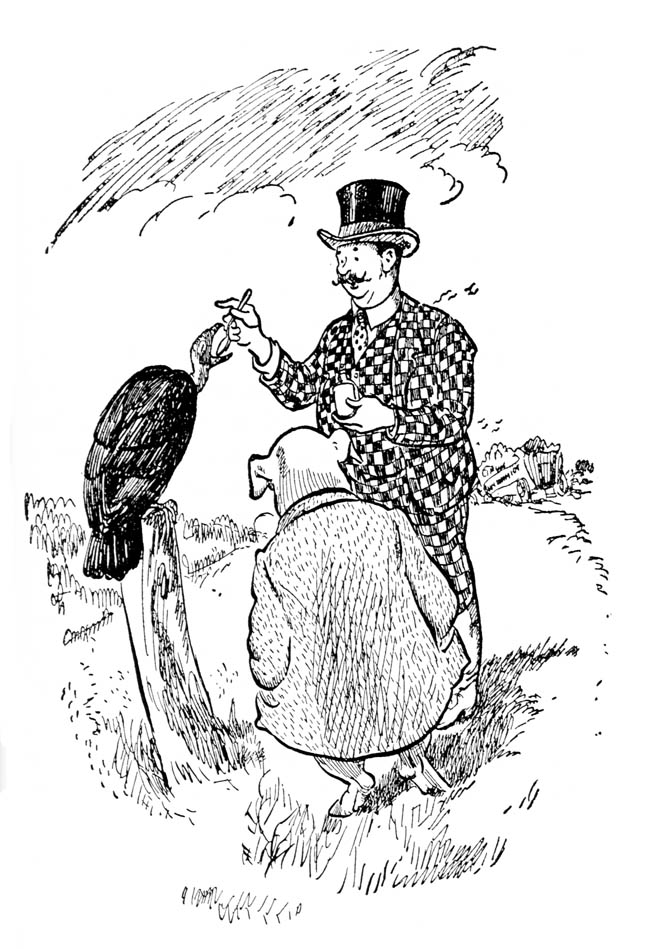

Phil agreed listlessly, and Freddy ran up to the head of the line and got Mr. Boomschmidt.

Mr. Boomschmidt always carried a bottle of castor oil and a tablespoon in his pocket when he was on the road, for as Freddy had said, one or another of the animals was always overeating, and it was too much trouble to hunt around in the wagons for the medicine when it was needed several times a day. He gave Phil a good dose.

He gave Phil a good dose.

To their surprise Phil didn’t try to get away, but opened his beak obediently, and even smacked it when the oil was all down.

“Right pleasant stuff,” he said. “What is it?”

“Castor oil,” said Mr. Boomschmidt.

“Never heard of it,” said Phil. “Why, I feel better already.”

“Good grief!” said Mr. Boomschmidt. “Where were you brought up?” Then he shoved his hat over to the back of his head and stared thoughtfully at the buzzard. “How’d you like to join our show?” he asked.

“Like it right well,” said Phil. “But what good would I be in a show?”

“Well,” said Mr. Boomschmidt, “there’s a lot of tidying up to do around the grounds after the show’s over. You could do that. But what I’d really like to have you for is to act as a good example to the other animals.”

“Me?” said Phil. “A buzzard can only be a good example to another buzzard, and as there ain’t any other—”

“Oh, my goodness,” said Mr. Boomschmidt, “let me do the talking, will you? See here; I have a lot of trouble getting my animals to take this oil. I can’t imagine why, can you, Leo? Eh, can you imagine why?—Oh, Leo isn’t here. Well, I’ll answer myself then. No, I can’t. Oh dear, now where was I?—Oh yes; oil. Well, you see, when one of ’em objects, then I can get you and give you some and show ’em how good you are about taking it, and then they’ll take it without any fuss. We won’t tell ’em you really like it. You can make faces—or maybe you don’t need to; your face … h’m. But you do like it, don’t you?”

“Try me,” said Phil.

So Mr. Boomschmidt gave him some more, and Phil smacked his beak again.

That was how Phil joined the circus.

So the show went on north, stopping at the larger towns to give performances, and at last they reached Centerboro. It has often been said that Mr. Boomschmidt gave the finest performance of his career there. But this has been written about so many times that I will not repeat here what everybody already knows. For those who wish to refresh their memory of this great event, however, I recommend the account published in Freddy’s newspaper, the Bean Home News, of that date. It is complete, well considered, and—I think—not too fulsome.

Mr. and Mrs. Bean were in a box right down close to the ring, and all the farm animals were with them. They clapped and cheered with the rest. But the act that really made the whole audience whistle and stamp until the big tent bulged out like a paper bag that you blow up, was the one that Freddy put on. He rounded up the mice who had been living in the barn he had rented, and he had them hide all around the edges of the tent and among the seats. Then a bugle blew, and Mr. Boomschmidt announced that the famous Pied Piper of Centerboro had been engaged at great expense to put on his unique and stupendous mouse-charming act. Then Freddy marched out in his Pied Piper suit, blowing the first seven notes of Yankee Doodle on his fife, and out from all sides the mice came scampering, and they lined up behind Freddy, and he marched them three times around the ring and then out to the dressing rooms.

It was a great success. Of course several ladies fainted away and had to be carried out and revived with smelling salts, but as Bill Wonks said, “A circus act ain’t really a success unless a few people get so scared they keel over.”

Indeed so great a success was it that Freddy stayed with the show nearly all summer, and gave his performance in most of the big towns of the eastern seaboard. For as long as he wasn’t a real partner, and really didn’t have to stay with the show, he didn’t mind. You see, he had accomplished what he had set out to do. Just as he had managed to get his path cleared of snow without having to do any shoveling himself, just so he had managed to raise the money and get it into Mr. Boomschmidt’s hands, without having to become a partner.

But one funny thing happened along in August. They had swung around through the southern part of New York State, and stopped to give a show in Tallmanville. Freddy and Leo didn’t join the parade through the town before the show. But they took their regular part in the performance, because they didn’t think that Mrs. Guffin cared for entertainments. Leo said she never went to anything.

But she came. She came along with the people who looked at the menagerie before the performance, and when she saw Leo she recognized him. She was pretty mad. She made quite a fuss in front of the cage. She told all the people around her what had happened in the spring, and of course her account of it wasn’t much like the truth, and some of the people got mad too and advised her to call a policeman. But she said no, she was going to do better than that. She was going to wait till Leo was doing his balancing act in the ring, and then she was going to get right up in her seat and denounce him, and Mr. Boomschmidt, who had probably stolen him from her. And then she would call the police.

Leo sent for Freddy.

“I don’t know what she can prove,” said the pig. “But I suppose she can make it unpleasant for us.”

“Well,” said Leo, “no use worrying the chief with it. He can’t do anything. We’ll just have to go on with the show.”

“Nothing else to do,” said Freddy. “I never thought she’d come around.”

Freddy’s act came just before Leo’s, and when he marched in, sure enough, there was Mrs. Guffin right down in front, and looking mad enough to chew carpets. Luckily she didn’t see beneath the Piper’s suit to the pig underneath.

And then when he started to blow Yankee Doodle—which by this time he had learned, all but the last half—the funny thing happened. For the ferocious Mrs. Guffin was afraid of just one thing on earth: she was afraid of mice. And when they came tumbling out from under the seats she gave a loud yell and fell over in a dead faint. It took four strong men to carry her out of the tent, and by the time she had come to enough to be mad again, the show was over.

“Well, curl my eyelashes!” said Leo. “I wish we’d known she was scared of mice when we were here before. We’d have had a lot easier time with her.”

“Oh, I suppose so,” said Freddy. “But it wouldn’t be as much fun to look back on. You know, if we knew everything beforehand, things wouldn’t be much fun, would they?”

That was really one of the smartest things Freddy ever said.