1

An East End Upbringing

Contrary to evidence, the children of Poplar, where I was born, were not always playing in the streets. Most of the time they were helping in the home or running errands; if not for the parents, then for neighbours or the local shopkeepers, earning small sums of money to help the household purse. Regular errand-running was an accepted practice, and children grew up reliable and trustworthy in handling money and goods. Some shops employed older children of twelve to thirteen years old, after school, to collect orders from their wholesalers: an early operation of the ‘Cash and Carry’ principle. Children of this age, too, dashed out all over the East End from newsagents shops, burdened with the afternoon and City editions of the evening papers.

One job that was quite laborious was the collecting-up of bottles of Chloride of Lime from one of two depots that distributed this essential disinfectant in the neighbourhood. One, in Poplar High Street, was down a long, cobbled alley where dozens of children would form lines with bags of two or more bottles; the élite might have a two- or four-wheeled wooden cart with a number of bottles or flagons for various neighbours. It would take more than one child to pull the load up the alley to the top of the hill. The Lime water was free, and did in some small way help to keep the drains clean. Many families used it in the washtub too.

In my own family, the three younger brothers had a regular sponsor for our services, being passed on in turn as each of us left school and started ‘real’ work. The next brother would be inducted, and the routine carried on without interruption. Our client was the local dentist, a bachelor; apart from shopping for him, once or twice a week we journeyed to Manor Park with a small attaché case full of denture moulds made from plaster-of-paris – a two-hour journey of two buses and a half-mile walk. This earned us a shilling per trip on top of the half-crown he paid us each week for six days’ worth of shopping.

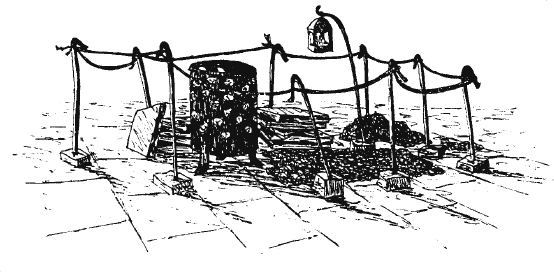

Some of the girls were honoured to be chosen to take out a new baby from time to time, to wheel them up and down in prams; or perhaps an infant in a pushchair. You would see a congregation of these young nursemaids with their charges. A special girls’ pastime in the spring and summer months, weather permitting, was to build grottoes from sheets of crêpe paper, fixed with bows to a wall, the pavement decorated with coloured paper, shells, postcards and any other oddments to brighten the effect, from where two or three girls would shake a tin at passers-by, calling out ‘penny for the grotto, please’. Any receipts would be shared between them.

Ignoring the ‘health and safety’ warning not to go near the water, a favourite summer pastime of barefoot children in the 1920s was chasing the water cart.

Other girls’ games included pavement skipping, a long rope held at either end by the largest children so that several others could join in the middle. Sometimes, the young mums would come out of their houses to give the girls a hand with turning and to see that fair play was exercised. Hopscotch, and ‘bonce and gobs’ – played sitting on a door mat – could only be played when there was no further work to be done in the home. Cricket, which the boys enjoyed, was played with a ‘wicket’ chalked on someone’s brick wall, and a bat made by a dad from a piece of wood. Test match rules applied, but with only three or four players; more, and some might not get an innings. Football was different, being played between goalposts made from boys’ caps. These would have to be rescued when horsedrawn carts and occasionally cars came by and, when opposition teams became threatening, would be placed closer together with many protests. The smallest and weakest children were usually made to go in goal. The ball, meanwhile, was made from a large bundle of newspaper, compressed and tied with string.

Leapfrog was a game for the taller boys, who could jump. The smaller boys would act as ‘pillows’ when the frog jump took place and anyone collapsing underneath would be called up as ‘weak horses’ and their team would lose. ‘German cricket’ was an all-year game consisting of four wooden staves, placed against a wall to form a wicket. A ball would be thrown and, if the wicket was knocked down, the thrower and his team would run away while the opposition chased them with the ball, aiming at a boy. If he was hit, they tried to eliminate the rest of the team. Meanwhile, the survivors would double back and re-erect the wicket – the ‘score’ was the number of wickets erected. ‘Tin Can Copper’ was a game enjoyed best of all when it was getting dark. An empty condensed milk tin would be thrown from a starting point such as a manhole cover, the thrower and his team would hide until one was discovered by the searchers, who would then station themselves at the manhole and declare, ‘Tin Copper Charlie’ or whatever the name was of the discovered child.

Whips and tops were plentiful at certain times of the year, as were peg tops, deftly wound with a cord and pulled sharply to get a good spin. Small ones made out of boxwood – ‘boxers’ – could be spun on the palm of your hand. Wooden hoops hit with a small stick would accompany children on errands, heavy steel hoops would be propelled with a ‘skimmer’, a short piece of strong wire with a hook at the end, in which the hoop would be kept spinning after a short run. These hoops could cause havoc when they caught in the live rail of the tramlines. Broken ones were mended by the blacksmith in his forge.

‘Tibby cat’ was a dangerous, if enjoyable game for older boys. A small oblong of wood with tapered ends was placed on the pavement and struck with some force to make it rise in the air, then dispatched with a bat along the street, the distance of the hit being paced out. Taller boys with longer strides had the advantage.

As soon as they arrived from school, however, most older boys and girls would have to light or brighten up the fire for the evening meal before their parents came home, if they both worked. Sometimes a chimney would catch fire, blanketing the neighbourhood with thick black smoke. They were rarely swept and some folk deliberately set them alight just to clear the soot and save the cost of a sweep.

Collecting cigarette cards by standing outside tobacco shops and badgering smokers was a regular pastime for the younger boys. The cards were swapped or exchanged for various offers, or used in card games – flicking or ‘skating’ nearest the wall, wins all. Army cap badges and regimental buttons were in good supply after the First World War, and collectable; as were foreign stamps, from which older children learned much of their geography. Fishing for sticklebacks and frogs was possible, if you were prepared to journey outside the area; Victoria Park or Beckton Road Tollgate ditch involved a long walk. You sometimes caught a fish in a net made from an old curtain, by dragging it along the stream. Barrel-organ buskers were popular, touring the pubs. One would dress as a woman and sing in a high voice, much to the amusement of the children sitting next to him on the kerb.

Children also had some devilish adventures. ‘Knock-down Ginger’ involved tying two neighbouring door knobs together and watching the results from hiding. Tying a piece of black thread to an empty cigarette packet or a coin, and placing the object in the path of a suspect, only to snatch it away as they bent down, was usually performed from basement steps in fading light. Police on the afternoon shift at Poplar station would march out with the sergeants in the lead; woe betide any children found up to pranks. Look-outs were posted, ready to call out when the enemy was sighted.

They were all little workers, friendly, gentle children in those days. Most had to grow up too quickly, adult heads on young shoulders. They were the salt of the earth in the next generation.

Poor and orphaned children depended on the Tabernacle, which provided a soup-and-bread kitchen service three times a week.

A group photograph of the children of the Tabernacle and helpers, 1911.

SCHOOLS

The good folk of Poplar owed a great deal to the London County Council, which controlled the running of about eighteen schools within a few square miles and ensured the education of children between the ages of five and fourteen – only a few went on to fifteen years at a couple of central grammar schools. The education was sound, and passed on by first-class teachers who accepted the production of bright pupils as a pleasure and reward for the hours of patience and devotion. Some of us must have been quite difficult to teach.

In my family we were five boys and two girls, all pupils of Culloden Street Elementary school. Each of us achieved a high standard, the youngest three following one another in becoming School Captain, under three different headmasters. Being the youngest, I can still hear the shrill whistle of the summons to the headmaster’s office, wherever I was among the 220 or more pupils spread over seven classes. My eldest sister won a scholarship to the élite George Green Grammar school in the East India Dock Road.

Culloden Street had an infants’ section for the five to seven-year-olds and a Senior Girls’ school separate from the boys. There was a metal workshop and a woodworking section, and a fine housewifery section for the girls, all operated by first-class tutors who had a hard job to pass on to children who would be leaving at fourteen, all the knowledge they could in such a short time. However much or little, it was more than they would get at home. These facilities were shared by neighbouring schools, and a well-planned rota ensured that all worked smoothly across a wide range of abilities. Timewasters were given short shrift.

Children press their pennies on The Okey Pokey Ice Cream Man. His brand was soon superseded by the ‘Stop Me and Buy One’ man from Wall’s.

The imposing Victorian figure of shipbuilder and philanthropist Richard George Green gazes sternly over the local pawnbroker’s shop out of picture. His dog, Hector, looks up from his feet admiringly. In the background is the King George Hall where we used to go for Saturday morning pictures. The grammar school that bore his name is nearby.

Hay Currie school in Bright Street was known for turning out very bright and well-behaved pupils. They were expected to shine under the public gaze, in the shared sections of Culloden Street, at the local swimming baths, and on Sports days. Oban Street and Bromley Hall Road pupils shared our facilities; Ricardo Street, near the Chrisp Street market, was a popular school, known for turning out good young boxers and blessed with several tough teachers of the no-nonsense type. St Leonard’s Street school bordered on the Limehouse Canal; North Street and Woolmore Street schools were on the other side. No pupil in the area had a long walk from home to desk. St Paul’s Road and Dingle Lane schools covered this area, while Millwall and the Isle of Dogs had East Ferry Road, Cahir Street, Glengall Road, Maria Street and Arcadia Street schools, all turning out very bright pupils.

The LCC were to be congratulated too, on their foresight in the 1920s and ’30s in starting evening classes to encourage learning in leisure time. On weekdays, table tennis, dancing, art and drama could be enjoyed; above all, the children of poor families were off the streets and out of mischief.

Several scholarships were available – Christ’s Hospital, Coopers’ Company, Junior County and Trades Scholarship winners were awarded places at the grammar schools and higher schools until they were fifteen or older, if the families could afford it. Many bright pupils were deprived of these chances at fourteen, as their families needed the extra income to supplement the family budget. Irish Catholic families were catered for, with schools at Wade Street, St Paul’s and the small church school of St Mathias in Grundy Street, which was mainly for very young children. Thomas Street Secondary school took boys and girls from other schools after they had won a scholarship place from the Trades scholarship. George Green Grammar school was the pinnacle for the district winners of the Junior County entrance exam, much to the annoyance of my mother and father, when my sister won it. They had counted on her bringing up the younger siblings, and to bring in some wages; the cost of the uniform put an additional strain on an already overstretched purse; but after a few years at George Green she rewarded them by becoming private secretary to the boss of a local engineering firm, earning a very good salary.

The preserve of the brainy few who could obtain scholarships, George Green’s schools in the East India Dock Road were founded in 1828. The building seen here in about 1900 was built in 1884 as the secondary school for girls and boys.

Schoolchildren, proud parents, teachers and governors listen to the singing on Empire Day, always celebrated on 24 May. We enjoyed it mostly for the half-holiday that followed the parade.

Discipline was tough. Memories of milk monitors shepherding us along the hall with the crates of third of a pint bottles and straws, urging the pupils to fall into line and drink up; inkwell monitors, taking the little china pots out of the desks on a Friday afternoon and down to the washroom, to dislodge the chewing gum and blotting paper that normally clogged up the little hole, and on Monday morning refilling and distributing them, ready for class. One of my Captain’s chores was to assemble the boys who were on lists in the various classes as needing the cod liver oil and malt supplement to give them extra nutrition. It was a job to collect the large tins from the cookery department, each holding about 7 lb of sticky malt, to lift and twist it on the spoon and to get it in the open mouth, not down the neck; then to wash and dry the spoon, ready for the next boy. Helping the nurse to bring in lads she needed to check was another ‘hurry up’ job. Teeth, hands, necks, legs, eyes were quickly scanned, those wanting a second look were stood to one side, or given a note for a parent to take them along to the Medical Centre for whatever treatment the nurse felt was needed.

Monday mornings were Country Holiday Fund collection times. This was a club founded by a charity which provided a fortnight’s holiday in the country once a year for children willing or able to save money towards it, the usual cost being ten shillings, payable between January and June. Some of the homes they were sent to left a lot to be desired, but it was a chance to get out of London. Memories of such holidays are fresh in my mind, I went on three – to Malvern, Maldon and Sudbury, Suffolk.

Crocodiles of children were a familiar sight, being herded along by teachers at front and rear between their schools and the swimming baths in Poplar, or the open-air baths at Violet Road, or Millwall Park in the summertime. Cricket practice was held on an asphalt area on Glaucus Street, surrounded by a high wire fence. It was a facility shared by all the local schools; Essex county cricket festivals were then a popular summer attraction. Borough track events were held at Victoria Park: teachers would implore the non-contestants to go along and cheer on Sports Day; a plea that fell on deaf ears, as it was officially a day off from school and many could not afford the train fare, which was free only to those taking part.

Being disabled, when I was very young the school board arranged for me to be transported daily to a small school with about 50 pupils, many much worse afflicted than myself, in Bromley-by-Bow, about four miles away. At the age of seven, I was assessed as being strong enough to join my brothers and one remaining sister at Culloden Street. Although unable to take part in sports, with endeavour I became Captain of the school and left at thirteen years, eleven months to enlist in the regular army of workers and wage earners, of which more later.

EAST INDIA DOCK ROAD

The East India Dock Road was one of the best-lit and most frequented walks for Poplar people. Overhead lighting and the blazing shop fronts made it a must for young and old to promenade, window-gaze, meet friends and do their courting – a great improvement on the dingy streets behind the main road. From the post office to Brunswick Road there were a great variety of shops, starting off with the jewellers and pawnbrokers, H. Neave; with the wool shop on the next corner adjacent to the Victoria Wine Company, alongside the Midland Bank at the corner of Chrisp Street market. The Poplar North London Railway ran under the road at this point, Poplar station also being the main stop for trams and buses. Next to the police station, a builders’ merchant supplied most of the landlords and the tradesmen they employed to patch up the thousands of terraced houses, many of them already a century old. The tenants were hard-pressed to get any but the most serious repairs done. Two sets of wallpaper books were displayed in the store; tenants were allowed to select up to half-a-dozen rolls, at 6d per roll – the cheapest quality – and put it up themselves, or pay someone to do it, if they could.

The police station was a majestic building. The entrance was up six stone steps and a constable stood on duty outside, keeping an eye on the passers-by and on the traffic. People would stop to read the notices and stare at the photographs of missing persons or people found drowned in the docks nearby, with requests for information. This was seldom forthcoming: anyone foolhardy enough to identify a body at the mortuary in the High Street, if there was no next-of-kin, would be charged with the burial expenses.

The two-storey Hippodrome cinema with the Aldgate tram passing, c. 1920.

A lovely bookshop, John Seager’s, was next, and supplied the needs of the schools and shops with birthday cards and stationery of every type. Next door to that was the best tobacconist in the area, smelling richly of the cigarettes, cigars, and snuff, which was weighed and sold loose. Cigarettes, too, could be bought singly. A men’s outfitters next door always had the latest collar styles on display. Detachable collars and cuffs meant that shirts stained with the city grime could be washed less frequently, lasting longer, and the styles were forever changing. Then came Waters’s restaurant, a small eating-house with bench seats at tables, crisp, white cloths set in long rows with a gangway between for the two waitresses, who collected the orders from a hatch at the end. The local schoolteachers came here at lunchtime, as there were no canteens in the schools.

One of the newest shops on the street was Peter Pan, a babywear store with a good selection of clothing for the mums of Poplar babes and toddlers. This was a precursor of today’s up-market shops; such a store had never been seen before in our part of London. The local chemist, Squire’s, offered a seven- to ten-day in-house developing service for the rollfilms they sold to those affluent enough to possess one of the new Kodak cameras, known as Box Brownies. The results were unpredictable, but a new generation of ‘snappers’ was nonetheless emerging. The Admiral Fried Fish shop offered a choice of eating-in or takeaway; next door, ‘the tailor of tomorrow’, Jack Emms stood on the corner of Ida Street. Brash new colours and styles, and the padded-shoulders look favoured by George Raft, were talking points for every family acquainted with the latest Hollywood movies. On the opposite corner was a Jewish dentist, Mo Lewis, a short, chubby man, always whistling, his sleeves rolled up his brawny arms, ready for work. He kept two caged parrots in the waiting room, partly as a distraction, but more to drown out the screams from the surgery. A bespoke tailor for Naval officers and other ‘gentlemen’, Wright’s, was next door; and next again, the National sweetshop, brightly lit and endlessly tempting to children, undecided where and on what to spend their pocket money. The smell of the cooked meats – faggots, saveloys, brawn – and pease pudding from Coucha’s was always appetising; they never seemed to close, apart from on Sundays.

Funeral processions were frequent events but few on the lavish scale that sent off London’s most famous publican, Charlie Brown, the ‘King of Limehouse’ and licensee of The Railway Tavern, in June 1932.

Wiffen’s was a studio photographer’s. His work was always worth stopping to look at, mounted in a glass case in the window. Every subject posed in the same chair, before the same backdrop. A watch repairer had the basement; in his window was a little doll swinging up and down, attached to the pendulum of a clock that always showed the correct time.

The coach station had blackboards outside, chalked with details of the day trips on offer, their times and prices – racecourses being popular destinations throughout the year. In the summer, and at holiday times, there were trips to the seaside. Noisily clattering and grinding next door, engineers McWhirther Roberts made galleys and ventilators for the ships in the docks. Some of the streets had electricity supplied by the Fixed Price Electric Company. You paid by the week, per fitting, and the firm sold its own, very low-wattage bulbs, that would only fit their fittings. This was a boon to many households still using gas mantles, or even oil lamps.

Abelsom’s the chemist was also along this parade, close to Mr Court, who had a large printing press. It was a pleasure to watch him working, assembling all the loose type in the frames and starting up the antiquated press, the sheets of paper churning out still damp with printer’s ink. The next shop had rack upon rack of suits and coats on parade, waiting for another kind of press, a Hoffman press with a padded top, that came down hard on the jackets and trousers that were then hung up, still steaming, to dry. There was no dry cleaning then, but a suit well-steamed and pressed was just the job for a wedding, funeral or a night out with the girlfriend. The Commercial Gas Company showroom was always well-lit, warm and inviting on dark winter days. It was a sight to see the shining rows of new model gas cookers, all enamelled – a huge improvement on the old iron ranges in the majority of the houses in the back streets, that were such a chore to clean.

Granditers, another menswear shop, always had a selection of smart styles for the younger man headed ‘up West’. Marks, the famous baker, displayed delicious loaves, cakes and wedding-cakes in glass cases, ready for the bride and her mother to inspect. Freshly baked, the tasty milk loaves and cream cakes gave off an aroma you could detect while still yards from the shop doorway. Another memorable smell came from Cardosi’s, the coffee shop that never seemed to close. This was a great meeting place for dockers and tram drivers at the end of their route; also for the many less savoury characters who traded goods that had ‘fallen off the back of a lorry’ or mysteriously gone absent from the dock cargo.

On the opposite side of the East India Dock Road, by the entrance to the Blackwall Tunnel, was a smaller parade of shops, among them the cut-price sweet shop, Karamels, offering savings of 3–4d off popular brands, and chunks of solid chocolate, broken to order by an assistant with a huge pair of tongs. The local eel and pie shop, Shaklady’s, was a godsend for late workers and patrons of the nearby Grand cinema, to eat in or take away for supper, conveniently situated next to the tram stop. And, further along, you came to Eaton’s, the ‘one and only oil shop’, that sold everything for the DIY decorator. There was always a display outside of two-gallon buckets, each painted a different colour – this was in the days before colour swatch cards – and you pointed the brown-coated assistant to the one you wanted made up. Balbe’s, the top-grade hairdressers for men and women, discreetly displayed a variety of contraceptive devices beneath the bottles of Anzora Hair Lotion, Pears’ Brilliantine, hairnets and tongs. ‘Something for the weekend, Sir?’

PARKS AND GARDENS

The London County Council and their forerunners did an excellent job of laying out the East India Dock Road along the mile or so from the Iron Bridge at the border of Canning Town, up to where it joins Commercial Road, gateway to the City of London. Everything anyone could want was there, including a hospital, three churches, two grammar schools, four cinemas, the Board of Trade offices and, between the fine, large houses, all carefully sited, were no fewer than three parks or ‘recreation grounds’.

Tunnel Avenue park was, as its name suggests, close to the Dock Road wall and the Blackwall Tunnel; a narrow, well-tended area with a lower level set aside for children. A long walkway led on to Blackwall pier, a pleasant walk on a fine day, where you came upon an excellent view of a bend in the river beside ancient steps for small craft to tie up when permitted. The walk ended at the railway station, serving travellers to and from the upper reaches of the river.

The neatly laid-out flower beds of All Saints’ Church gardens were a welcome retreat from the hustle and bustle of the East India Dock Road. Jewish folk attending the popular synagogue would congregate in the gardens, by the side entrance. Gates in the distance led to the large houses and surgeries of the local ‘panel doctors’, as they were called then; GPs now, I suppose. The gardens were most popular at weekends when couples getting married would pose for photographs with their guests after the service; a happy and memorable event, especially when a peal of bells had been paid for, for the crowd of wellwishers gawping through the park railings.

Children paddling in Victoria Park: an occasional treat for the author and family at Easter, Whitsun or on someone’s birthday. (Photograph courtesy of Sam Vincent)

The small playground in Newby Place, although listed as a park, was in fact an enclosed area for children, close to the East India Dock Road. There were swings, roundabouts and slides to keep offspring occupied under the supervision of a well-bribed elder sister, while Mum went off shopping in nearby Chrisp Street. But the ‘Jewel in the Crown’ of Poplar parks was surely the Recreation Ground. On entering the gates, your attention was immediately drawn to the lovely angel statue, erected in memory of the little children from North Street school, killed in a Zeppelin raid during the First World War. Their names are engraved on the base and can still be seen today. There were tennis courts for dedicated players, oblivious to the taunts and stares of passers-by. The floral gardens were cheerfully immaculate, and supplied from their own greenhouse. An old dear supervised the children’s play area from her eyrie in a wooden hut. Several generations of us knew her only as Miss Taylor, and she kept a small cane handy for quickly settling any disputes over swing ownership.

The Bowls Club were ensconced on an excellent green at the far end of the ground. It was a grand spot to sit and observe the talent and skill of the locals. This and all of the parks were supervised, and a high standard of care was always maintained by the park-keepers. Millwall Park, finally, was the gardens leading to the pedestrian tunnel under the Thames near Cubitt Town, and gave a wonderful view of the river and the magnificent National Maritime College on the far bank. Poplar residents were proud of their green spaces, which were such a boon to mums when the long school holidays were upon them.

ENTERTAINMENT

In the days before the television invaded people’s living rooms, entertainment in the homes of Poplar, as elsewhere, consisted probably of a wind-up 78rpm gramophone with sharpened wood or steel needles in a tray next to the curiously jointed playing arm; a piano, which might be found in the front rooms or parlours of the aspiring middle classes, few of whom, if any, could play it; and an early form of wireless known as a crystal set, with a primitive valve or ‘cat’s whisker’, whose pair of headphones could be split so that two people could listen while the rest of the family sat in impotent silence. At party time, a piano player would be imported from another street, or an invited guest would suddenly reveal hidden talents, and a sing-song would ensue.

From these modest home comforts, leisure sights were then fixed on the Picture Palaces, or cinemas as they came to be called. The Pavilion, in the East India Dock Road, was the first in the district to offer talking pictures, and long queues formed to see and hear Al Jolson in The Singing Fool, with not a dry eye in the house during his famous rendition of ‘Sonny Boy’. Gaining admission was a challenge, with a commissionaire to keep the lines in order and now and again announce that there was ‘Standing room only in the sixpenny seats’ while the more expensive ninepenny seats were always available. Having succeeded in gaining a seat, and they were very comfortable, many in the audience would stay and see the film through twice. Peanut vendors and buskers gleaned a living from the captive audience. Next door was the well-known sarsaparilla shop with, outside, a red-painted stall with barrels and taps ready to dispense this thirst-quenching and doubtless medicinal liquid to cinema patrons.

Like the Pavilion, the Grand in Tunnel Avenue, next to the Blackwall Tunnel, was a single-storey building with a sloping floor whose gradient hastened you to your seat. People kept exiting annoyingly by the push-bar doors, letting in both daylight across the front of the screen, and pals of the youths inside, hoping to gain free admission. Hearing the loud protests from the courting couples lit up by these sudden interruptions, the usherette or manager would rush to close the offending door and evict the freeloader. At the back of these cinemas, the standing-room-only patrons would watch patiently, resting on a brass rail, until the usherette came along the line with the welcome words ‘two singles, or ‘one double seat’ and then you followed her torch along the aisle. People were always changing seats to avoid a fat lady or a giant with a large hat obscuring your view, and hissing at one another to keep quiet.

On the corner of Stainsby Road and East India Dock Road was a two-storey cinema, the Hippodrome. You entered the gallery via the stone steps in Stainsby Road, the pay box being let into the wall about three flights up. The staircase usually reeked of carbolic. Customers for the dearer stalls seats were allowed through the main entrance, past the publicity ‘stills’ of bygone stars and details of the coming attractions. Up in the gallery, the seats were of the tip-up wooden variety, about twelve rows, from where missiles and other detritus could be showered on the less fortunate audience who occupied the plush seats, directly below.

The Grand Palace Picture Theatre stood opposite the Blackwall Tunnel next to The Volunteer pub.

The Gaiety was near the Hippodrome but a much smaller cinema, single-storey, and specialised in matinée programmes, much preferred by the older folk because of the tea interval. For children, St George’s Hall near Chrisp Street market provided a Saturday morning showing with a single price of twopence. Several hundred children shouting at the villains and cheering on the cavalry could be heard over a great distance.

The Tabernacle in Brunswick Road was a church mission hall that offered children a restricted weekly showing on a Thursday afternoon, for one penny. Rather old-fashioned, it showed mainly magic lantern slides; but the regular Felix the Cat cartoon went down better with the children, who all joined in singing ‘Felix Kept on Walking’. At the end of Poplar High Street was a low-grade, single-storey fleapit with a corrugated iron roof and wooden benches bolted to the floor, optimistically named the Ideal Cinema. Lascars from the ships in the West India Dock, Chinese from Pennyfields and other strangers comprised the best part of the audience; you never knew the nationality of the person sitting next to you.

Then there was the music hall. Poplar boasted only one, but what a one! The famous Queen’s Theatre in the High Street was the launchpad for many well-known stars of the era. Pictures of Gracie Fields and her then partner and agent, Archie Pitt, and many others adorned the foyer. Bills were posted all over the district, listing the full variety programme; inside the theatre, the acts were displayed in lighted frames, with the top of the bill appearing about halfway through, by which time the audience would have warmed up enough to meet their expectations of applause. Outside, a hot potato and chestnut stall did a roaring trade on Friday nights, after people had been paid their wages. Every year after Christmas, for many years, the theatre was hired out for a pantomime, when hundreds of children each received a special treat, a pink and white marzipan fish, with a chocolate stripe on its back – courtesy of Clarnico, the local sweet factory.

Venturing out of the neighbourhood, a special night out was to the ultra-modern Troxy Cinema in Commercial Road, Stepney. As well as the pick of the latest film releases there was a theatre organ that rose magnificently out of the orchestra pit into the floodlights and played the hit tunes of the day while the audience were taking their seats, and it appeared again during the interval. On Friday and Saturday nights there would be a guest live act, such as the enormously popular sand-dancers Wilson, Keppel and Betty. I can still smell the perfume the management sprayed everywhere in the theatre, making an evening in its warm, enfolding comfort seem even more magical.

PARADES

On Sunday mornings the streets would be enlivened by the Boy Scouts, marching in their smart uniforms under the controlling direction of the Scoutmaster. Rivalling them would be the Boys’ Brigade with their pillbox hats, some with a small pouch at their hip, hung on a white webbing belt. The Poplar Hospital carnival was one of the most enjoyable, so many young doctors, students, nurses, orderlies and volunteers willing to help raise funds for the welfare of the patients and staff. The main source of income came from the shipping lines who sponsored the hospital wards, and from the lightermen who plied their trade on the Thames; together, they were responsible for supplying many of the patients, too! I spent some time as one myself.

On Saints’ days there were Catholic processions, not much to the liking of the Protestants. Four bearers shouldered the Virgin and child, another three carried the Crucifixion. The little girls were dressed all in white and swung incense burners, which brought colour and drama to the whole day. The hymns and solemn music echoed for a long time as the column wound its way along the roads. Devout Catholics would put out little shrines, to be blessed by the priest. These made a nice scene in the evening, with their candles burning in the windows. On Armistice Day, the ships’ sirens signalled the start of the two minutes’ silence at 11 a.m. It was something you never forgot. Now and then, ‘The Last Post’ would be heard and the factory hooters sounded and life started again.

The Oxford v. Cambridge Boat Race was another occasion for public display. Even the poor people of Poplar, few if any of whom would ever win a place at one of those exalted universities, really did enter into the competitive spirit, with families dividing into Light Blue and Dark Blue supporters, wearing their coloured ribbons. On the day, hawkers would take up pitches in the market, selling light and dark blue rosettes and celluloid dolls from boards mounted on wooden poles. They all charged exactly the same prices. The result of the race would not be known until later in the evening, by word of mouth, and was confirmed on Sunday morning by a headline on the newsagent’s hoarding. Not many people had radios, and few in Poplar even read newspapers in those days.