2

Hospitals, Trams, Shops

& Streets

A densely populated area like Poplar, with deep poverty existing alongside heavy industry and a bustling commercial docks area, was bound to put a strain on the doctors, hospitals and health visitors who served it. The Poplar Hospital for Accidents, its correct name, was perfectly sited opposite the East India Dock gate to deal with the medical emergencies that were always occurring in the busy East India, West India and Millwall docks. The long, polished wooden forms on which you sat patiently waiting your turn were filled with casualties from among the ships’ crews, dockers and stevedores, as well as with the borough’s own ‘accidents’; including me, twice: aged eighteen months after a major accident at home, and again at fourteen, when a near-fatal accident put me in their care for over four months!

St Katherine’s Maternity and Child Welfare Clinic, Brunswick Road, c. 1935. In 1921 the author received ultra-violet ray treatment for his paralysed arm and leg but states that it brought little benefit other than a nice tan. The building on the left was Bromley Library. The clinic was slightly bomb-damaged and was demolished in 1952.

The author had two six-month spells as a baby and teenager here in the Poplar Hospital. Founded in the East India Dock Road in 1855 for the casualties of maritime and dockland accidents, it was sponsored by the big shipping lines and closed in 1975.

More serious emergencies would arrive by ambulance at one of the side entrances. The reception area was open twenty-four hours a day. The blue-uniformed nurses and sisters were firm, efficient, reassuring, sympathetic and experienced in dealing with the whole spectrum of human misery, from birth to death. Above the ground floor, the wards were named after the shipping lines that had originally sponsored them: Ellerman, Shaw Saville and Cunard, to name a few. Sailors of all nationalities were treated, the language barrier being an added difficulty for the staff. Patients on the mend would sit in the open on the roadside balconies outside the wards and chat to the passers-by, often an efficient method of transmitting a message to friends and family.

St Andrew’s Hospital, on the border of Poplar and Bromley-by-Bow, carried a huge weight of the medically ill population. As well as accident cases it had a busy maternity wing; while among those who were brought in by ambulance, wrapped in long, red blankets, might well be patients with infectious diseases; TB, typhus and scarlet fever were rife. Cases would be rapidly diagnosed and sent out of the borough to special isolation hospitals. Visiting arrangements were odd but unavoidable. The hospital layout consisted of a very long corridor on two floors – wards led off on either side, and the offices, nurses’ quarters and operating theatres were all adjacent. But the intake area was very small; at visiting time, in all weathers, hundreds of anxious family and friends stood outside waiting for the gatekeeper to let them in. On the word, the sound of this army of tramping feet would filter into the wards, and patients would know their loved ones were coming. Sometimes, however, the wards themselves would be locked for administrative reasons and precious minutes lost. When the time came to leave, a bell sounded, and that was it, out! No more than two persons were allowed at the bedside at any time, so a lot of waiting around was involved.

St Andrew’s Hospital, Devons Road, Bromley-by-Bow, c. 1934. The building was opened in 1871 as the Poplar and Stepney Sick Asylum for workhouse inmates requiring medical attention, of what quality is not recorded. The name was changed in 1920.

Before 1946 and the arrival of the National Health Service, you were asked to pay if you could. The lady almoner would see relatives in her office, but payment was not compulsory. Hospital Saving Association members were on a sort of private insurance and benefited from ‘free’ treatment. Investing in a green voucher each week for a few pennies took a lot of weight off a breadwinner’s mind.

The treatment centre in East India Dock Road was really a large house. The rooms were converted into specialist areas for children sent by the visiting nurses at the local schools. Ears, noses and throats one day, eyes another. Any cuts or sores were treated on the spot and the patient sent back. Undernourished children, and those considered poorly, were weighed and examined by a small panel of doctors. If it was more than just feeding up they needed, they were referred to the Children’s Hospital outside the borough. A long line of mothers and children formed outside in all weathers, waiting for the doors to open. The disinfectant and ether smells seemed to cling to your clothes afterwards – for days, sometimes.

A view across the junction to Poplar Hospital, taken in about 1950. The building was demolished in 1981/2.

The Little Sisters had a small convent at the top of Bazelly Street. Run by some lovely nuns, it was there to help poor families, sick or injured, or those needing maternity care. As a crippled lad I tried to run with the other children and would trip up in the potholed side streets, my poor knees constantly cut and scarred. Mother would wash the injury and tie it with a rag, then, armed with a few coppers for the offertory box, I would be taken to the green-painted door, usually by an elder brother, ring the bell, and be shown into a spotlessly clean, white room. A white-uniformed nun would come in and greet us with a smile to bathe and dress my wound with Peroxide. Stiffly bandaged, I would emerge tearful – because it stung, and because I was unable to play with my ‘gang’. If it didn’t heal, I was to go back in two days, I was told. Those ladies were like angels to us and many other families in Poplar.

TRAMS, BUSES AND TRAINS

Although there were very few private cars, Poplar in the 1920s was well-served for transport. Trams, buses and trains took thousands of workers out of the borough on the six working days of the week and brought them back in the evenings. But the seventh day was almost as busy, on reduced schedules. The tram service from the border with West Ham was at Abbot’s Road and from here the service ran to Aldgate or Bloomsbury. It was an excellent service and the workers made a great rush in the early mornings to obtain a workman’s ticket, a valuable saving.

The London County Council, who owned the service, knew how to move large numbers quickly and cheaply. A one-shilling-all-day ticket – sixpence for under-fourteens – took you all over the capital on a network of trams. This was a boon during the holidays. No one was allowed on at the terminuses until the change-round operation was complete. This involved the reversal of the under-bogey and the careful manipulation of the live overhead conductor pole, and the flipping back of the seatbacks to give passengers a forward view. One major drawback of tram travel was that you could not alight between stops – the traffic behind would not stop for you, it being difficult to stop a pair of heavy dray horses pulling a load quickly. The iron-banded wheels would go into a long, sideways skid, and the cart would demolish everything in its path, including you.

A view of the East India Dock Road, where the Aldgate tram is picking up passengers outside Poplar station on the North London Railway. The tramlines were something of a hazard for horse-drawn vehicles like the one seen here. (© Ed Richardson)

Trams in Whitechapel High Street, 1932. Gardiner’s department store is on the right.

The buses of the London General Omnibus Company were fitted with solid rubber tyres and were nicknamed ‘boneshakers’. They ran services to all points of the compass: to Wanstead and Dagenham in the east, Paddington and Marylebone in the west, Brixton and Blackheath in the south, Hackney and Stoke Newington in the north. The LGOC had serious competitors, known as ‘the pirates’. Atlas was one, a notorious bus service that poached passengers along one of the more lucrative routes into the City. Always a few coppers cheaper, they got you there quicker. They stopped only where passengers wanted them to, and you had to be quick getting off as the drivers were on a time rate. They and the conductors played up the ‘pirate’ image by wearing their peaked caps at a jaunty angle. Chocolate-coloured Atlas buses were frequently to be seen hurtling past the sober red of the LGOC buses.

The North London Railway was a neat outfit that carried a few passengers going out of the area not covered by the bus and tram routes. South Bromley, Victoria Park and Hackney Wick were all covered and factories in those areas found the railway useful for carrying goods traffic. Schoolchildren who were transported to Victoria Park on Sports Days – for free if they were participating – will remember the delicious Nestlé chocolate bars that could be seen behind the glass front of the vending machine there; one good thump when the porter wasn’t looking might deliver an extra one free.

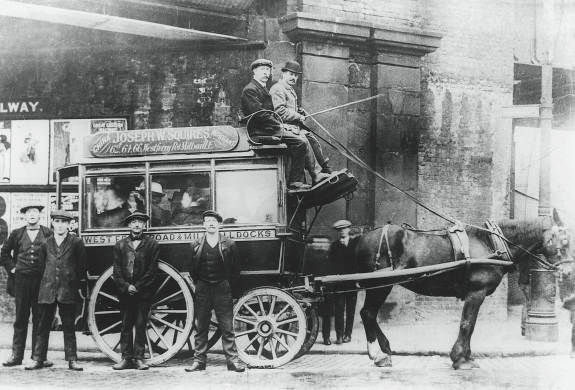

Outside the railway station in West India Dock Road, the horse bus served Millwall and one side of Cubitt Town, bringing the foreign seamen off the boats to sample the ‘fleshpots’ of Poplar!

A long-forgotten service that Poplar enjoyed was the famous Carter Paterson Parcel Delivery Service. These green collection vans ran a unique service to many parts of the kingdom. If you lived on a delivery route, you placed the CP card in your window and they would collect, weigh your parcel, check the destination address and charge you the delivery fee from a tariff. You were issued a receipt and away the goods would go, via their main depot in Goswell Street, Clerkenwell, to every part of the country.

Most deliveries were still by horse and cart, with two or more dray horses pulling sometimes very heavy loads. A wide range of goods was carried, and with the large number of pubs in Poplar, brewers Mann’s, Crossman, Whitbread and Courage made daily deliveries of beer barrels and crates of bottles direct to the cellars, whose doors opened at pavement level. The carter would lower the barrels down the ramp on ropes, while the horses stood quietly nosing in the feed bags strapped to their heads. Steam-powered vehicles were also around, brightly painted traction engines made by Foden’s polluting the air, belching clouds of smoke from the newly stacked furnace until, with a puff of steam and a cheery hoot, they rumbled on their way.

Albert Coe, Grover and Beattie, the familiar coal merchants of Poplar, were a hardworking lot. They had to cover every street in the borough; while, now and then, an interloper would appear, selling a dubious type of coal at a lower price. A lot was unburnable, or just fine sweepings known as ‘nutty slack’. A few shops stocked bags of coke, coal with the gas extracted, which would be collected from one of the three gasworks in Poplar, Bow and Greenwich. The shopkeepers could be seen pushing these bags on their market barrows, heavy loads for such a small return.

A more modern ‘Vulcan’ bus outside the Railway Tavern with, on the open top deck, a party of excursionists, probably on their way to Southend, at four hours about the longest journey they would have made in those days on solid rubber tyres.

Grove Road and the Great Eastern Railway bridge and station.

The Council, too, was a carrier, its open-topped dustcarts always on the move through the streets. A small army of dustmen lifted the rubbish from the battered bins that had mostly lost their lids, blown off in the wind or been ‘borrowed’. The road sweepers attached to this cleaning brigade had little, three-wheeled, open carts. Armed with a big shovel and broom they would sweep the pavements and unblock the gutters. This meant demolishing the dams so carefully constructed by boys to float an armada of matchsticks or other wooden craft that ended up as sunken submarines. During hot and, occasionally, drought spells, the water cart would be trundled out to spray the streets and keep the noxious dust down. To protect the public against the small amount of disinfectant added, it bore a warning sign – Danger, Do Not Drink This Water. Naturally, this entertainment delighted the neighbourhood children, who would splash about gaily in the spray of water, shoes tied around their necks, as the horse slowly pulled the tanker along.

SHOPS

How the local shops used to help mothers to resolve family problems at mealtimes is not something you read much about; yet shopkeepers must have saved many a marriage that could otherwise have run into serious trouble. Open All Hours, the title of a Ronnie Barker show, was an apt description of the shops in Poplar then, and, of course, throughout the East End of London. The goods they stocked were the stuff of legend, are mostly unobtainable today and, if they didn’t stock them, most shopkeepers would be only too delighted to get things for you, often at short notice. A number of shops are illustrated in the following pages. As a regular ‘runner of errands’ for my Mum and our neighbours, I had a good idea of who stocked what. Of course, there were few price-cutting ‘special offers’ in those days, and a good deal of borrowing of various commodities went on between one shop and another nearby.

Unlike modern, impersonal supermarkets, the role shops played in the community was important and varied. They would take a telephone message in times of illness, bereavement or childbirth. All kinds of messages could be passed on to their best customers and news exchanged. Young children would be casually employed on short journeys, collecting and delivering goods from other stores to assist in the prompt delivery of orders; and lifts given.

For the poorest people in the East End, food could often only be bought when daily wages were paid. Casual workers formed most of the population of every street, particularly just after the First World War. Most of the families were young; few children were old enough to work and earn a small wage. Consequently, ‘the slate’, sometimes known as ‘on the book’, was a rough and ready form of credit which enabled many a family to feed itself. The shopkeeper had to rely on the honesty of his customers to pay part, if not all, of their monthly bill before starting a fresh slate or page. Inevitably, debts were incurred, and in extreme cases the borrowers would be unable to get any further credit. Then they would approach another shop and plead for help, relying on the generosity of the shopkeeper to feed their family.

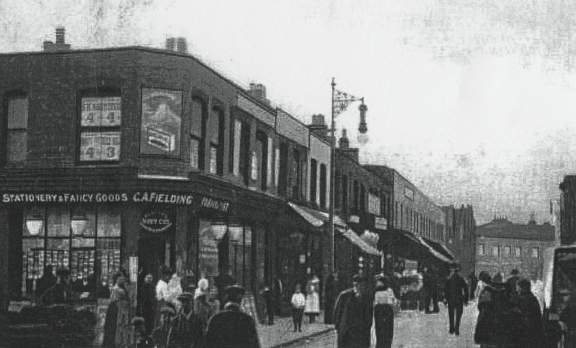

A busy street scene with shoppers outside Fielding’s stationers, Watney Street.

Running an errand for a neighbour, I remember once being given a note to take to the shop, requesting some items for dinner. This was handed back to me with a message to tell the lady there were three weeks’ bills to be cleared before the shop would supply any further items. My mother was cross with the sender. Why didn’t she send one of her own children, or go herself to plead for credit? Being disabled myself, I felt the shopkeeper might have shown me a bit more sympathy. But it was a sad, and not uncommon episode.

The journey into these shops was an education. I used to read the greeting cards, hanging in rows on hooks on the ceiling. There were hairpins in shiny paper rolls and hair slides of many colours; flypapers; Melrose for chilblains; Carter’s Little Liver Pills; Beecham’s Pills in little round, mysterious boxes, each containing a twisted piece of paper with two or three pills; Union Jack corn paste; one-inch bandages in blue paper; Ex-Lax chocolate and ‘worm cakes’ kept neatly by the side of the till. At the toiletries end of the counter were Lifebuoy soap, Sunlight and Carbosil – an early method of softening washing water; there was Robin Starch in little square boxes with a pretty robin, and Reckitt’s Blue bags, packets of soda and rows of nicely turned, smooth wooden clothes pegs that lasted longer than the ones the gypsies hawked ‘on the knock’, although they were cheaper.

Then, the food counter, with its conical blue paper bags ready to accept brown sugar, the only type available before the granulated version appeared, and tins of Lyle’s Golden Syrup, with the lazy lion fast asleep. I always wondered why he wasn’t roaring! There was treacle, which we never bought, and rows of stone jars of jam and marmalade, with the famous Robertson’s Golliwog, now politically incorrect. There was tea in penny packets, always a best-seller to the factory workers, and quarter-pound bags of Brooke Bond, Lyons, or – a name that always tickled me – Mazawattee tea. The name was signwritten on the delivery van that brought it. The cheese counter, too, with its wooden-handled wire cutter; rows of glass-topped tins showing the biscuits that would be bagged up round the front of the counter, the assistant reaching back to place them on the scales.

Placed conveniently at the back of the store, bundles of firewood tied with tarry string, smelling of creosote, were kept well away from the food. Some shops had a backyard where there was a paraffin dispenser with a brass tap; a little bucket hung under the tap would recycle the drips: ‘waste not, want not’. The big yards were also stores for brooms: house brooms, big bristle-heads and replacement handles of all lengths and diameters, stored under cover in a round drum to keep them dry. The little corner shops always seemed so cosy and clean, they were just the front rooms of people’s houses. Your entrance was announced by the little bell that tinged as you pushed the door open. Somebody would come along the passageway from the back of the house to enquire what you wanted. They had few items to sell, our nearest sold only milk, butter and cheese. New-laid eggs were sometimes available for invalids or were taken to the hospital if especially ordered (when the backyard hens were not on strike!).

There was a special shop at the bottom of Chrisp Street. This was the children’s delight, Inkey’s. The front room was decked out with trays of toffee flats, about one inch round and a quarter-inch thick. Next to this were rows of toffee-apples on rough-cut sticks, each one shining with a clear film of toffee. The large apples often had a nice, round lump of toffee stuck on the top, which had run down while the toffee was setting, to provide an extra treat. Sweet shops, as I shall explain next, were the hub of every child’s existence in the 1920s and ’30s.

Devons Road, Bromley-by-Bow.

FARTHING, HA’PENNY, PENNY

We were blessed with no fewer than three sweetshops within a short distance of our house. What a wonderful range of sweets could be bought in those days, for a farthing, ha’penny or a penny. The boxes were always open and the contents displayed within a few inches of your eyes; none of that wasteful wrapping you get now. Magnificently flavoured toffee: treacle, creamy banana or liquorice, broken into small, chewy pieces with a toffee-hammer. There were fruit gums, American hard gums, wine gums and, of course, milk gums, sickly sweet. There was Spanish liquorice, in many forms, real sherbet dabs, with a toffee on a stick to dip in, and Barratt’s sherbet fountains in the familiar cylinder with a tube of black liquorice for you to suck your sherbet through.

Mints came in many forms: extra strong, imperials, chocolate mints, mint lumps wrapped in paper; chocolate loose or in small bars for a farthing, always eaten before you got out of the door. There were Shuttleworth’s chocolate squares that had to be broken with pincers and wrapped bars of Nestlé with red and silver paper which came in penny and twopenny sizes and were also available from machines on railway stations. Everyone gave the glass front a thump to see if a free bar would drop before their train came.

There were gobstoppers that changed colour with almost every lick, all sorts of candy with a liquorice insert that could be separated before devouring, stick jaw, cough candy, coconut ice, brandy balls, clove bullseyes and, of course, for the girls, Love Hearts with gooey messages. There were alphabet letters, with which toddlers could spell out words before eating them, and Fry’s chocolate bars, in five sections, each with a boy’s face moulded into them. We had broken rock covered in sugar and most likely softened by age, small boxes of Imps: tiny pieces of medicinal liquorice, fiery hot to taste, that would give you tummy-ache if you ate too many. There was liquorice root that you chewed till it was dry and stringy, and tiger nuts – what these were, and where they came from, never bothered me, but every now and then you would get a small stone in one, which would hurt your teeth. Presiding over it all in a poster on the wall was the Sharp’s man in a bowler hat, advertising deliciously creamy toffee.

Lucky dips were a legend in the East End shops, most commonly thumbed and grubby envelopes in a small box, which, for a ha’penny, you could fish out to see if you had won anything inside. Every one a winner, prizes ranged from half an ounce to half a pound. If you were lucky enough to win the big one, news soon spread. Other children would magically appear, proclaiming their friendship and seeking to share in your prize. The envelopes would be replaced from time to time, to stop children marking them. Another Lucky Dip consisted of a ha’penny stick of rock, about five inches long. If a black spot was displayed in the middle when you broke it in half, you won the larger stick on display. I often wondered where I could hide it on the way to school.

A favourite of the smaller children was the surprise packet. Little girls loved to open them and eat the scented cashews while searching for the gold ring or packet of transfers inside. These you stuck to the back of your hand and, when dry, peeled off to reveal a perfect colour ‘tattoo’. Boys preferred to spend a penny or two on a box of caps. These small gunpowder charges could be placed between two steel ‘droppers’, tied with string, and thrown in the air, to land with a satisfactory explosion.

Novelty sweets were also popular; liquorice bent into different shapes like pipes, pinwheels, twists and bootlaces; soft yellow bananas and pink and white marshmallows, some covered in toasted brown coconut. There were rice paper ‘flying saucers’ of sherbet but it was Pontefract cakes – small buttons of soft liquorice – that were my wife Lilian’s favourite.

Every July, one shop put up an attractive poster encouraging children to join the Squirrel Club. This had a picture of a cute red squirrel, now almost extinct in Britain, happily surrounded by boxes of Christmas sweets ranging from one to ten shillings in price. You could collect stamps for a ha’penny or a penny, to help you save for the festive delights on show; I never did, as I feared what might happen if I lost it.

The bigger shops along the main roads were a joy. At Easter, their windows were filled with huge eggs wrapped in ribbon and silver paper with chocolates spilling out from the centre. They were surrounded by smaller boxed eggs in eggcups and mugs or just wrapped in gaudy, multi-coloured foil. The smell of chocolate wafting from these shops was heavenly. The Christmas display, with long stockings packed with goodies, also thoughtfully provided smaller stocking-items for the less well-off. One window had two-tone marzipan fish, labelled with the manufacturer’s compliments: Clarnico, promising that every child who attended their pantomime at the Queen’s Theatre would receive one free, along with an apple or orange donated by the market traders.

When the festive season ended, this shop had a sale and filled its window with bargain lines. They also specialised in a sweet called ‘Chicken bones’; long, thin tubes of brittle toffee, they had a creamy filling and broke easily – like the equally fragile nut rock pyramids they were tricky to share with your friends!

Having older brothers and sisters meant that pocket money came my way from errands. Running messages, delivering things or collecting clothes from the cleaner’s for a copper or two could be a lucrative business, but could also go wrong, especially if you delivered the message to the wrong person. When I got my cash reward a small group of followers would appear, as if from nowhere. ‘’ow much yer got? What yer goin’ ter get?’ Sometimes the shopkeeper would ask who was actually the buyer, then the rest would be turned out to stare longingly through the window, hoping I would buy a big enough bag to share. Older children in charge of smaller ones in prams would be seen supplying the child a small, coloured toffee apple, which cost a ha’penny. This invariably ended in a sticky mess but kept the young ’uns quiet.

A nearby off-licence sold sweets and boxes of chocolate. Cadbury’s had a range with pictures of the king and queen on the front, with a large bow. Caley’s sold bars that tasted more like wax than chocolate, but were cheaper than Terry’s, Fry’s or Nestlé’s. This shop also sold monster penny bottles of coloured ‘pop’, which had to be drunk on the premises or it cost an extra penny. Toys were also sold in these shops such as clay marbles, as well as the more prized, coloured glass variety. There were also spinning tops, and ‘boxers’ – miniature tops made out of polished wood which lasted for years if not lost or mistreated.

ROADS AND PAVEMENTS

Borough Council workmen do not receive sufficient attention or gratitude from the public. As children, we loved the excitement and, of course, the change of scene and the disruption to daily life that came with the replacement of the pavements in our street. Some housewives proudly whitened their front doorstep and a half-circle of pavement around it, as their mums and grans had before them. This was a hard chore the young women were obliged to perform. After beating the front mat against the wall and sweeping the dust into the gutter, a large block of whitening and a wet cloth would be artistically employed, sometimes across as much as a third of the narrow pavement, forcing passers-by to walk perilously near the kerb, while Mum kept an eagle eye on her drying artwork. Once the door was closed, of course, pedestrians took no further heed and the operation was repeated the following week.

The lifting and placing of the York stone squares was a skilful but heavy job, sometimes taking two men; though usually there was one very large, heavily built man chosen for his size and weight. He would lift and drop the slabs in just the right spot on the sandy bed and, with the back of his shovel, push the edges square and in line, all along the street. When all had been laid, the sand filler would get on his hands and knees to fill in the gaps, a process that had to be repeated several times as the sand settled. Fragments of broken paving slabs made excellent sharpening stones and other tools. My father had two or three in our backyard, serving as anvils to straighten bent nails that were never thrown away, recovered from the broken boxes that mother used for kindling wood. One well-worn slab was used solely for sharpening carving knives, the stone wetted with water from an old milk tin on the shelf above. Other stones when put side-by-side formed a level surface for standing things on, such as small items to be painted.

Workmen replacing stone cobble setts outside the Sailors’ Palace in the West India Dock Road. Russell’s sheet metal merchants is seen beyond.

To obtain these items, householders would be friendly towards the pavement men, and of course the publicans and shopkeepers would come forward with a glass of beer or a can of hot tea. In later years, however, the broken slabs all went back to the borough to be sold for crazy paving or hardcore. As prosperity increased, people would acquire pieces of stone or concrete flags to make paths over their muddy gardens, to the outside w.c. or the water tap; the modest charge for half-a-ton or so helped to remove the large quantities of rubble from streets that needed repairing after years of neglect by cash-strapped councils.

The road repair gangs arrived with horses and carts loaded with a tremendous variety of equipment. This included the workmen’s hut, a long tunnel of half-hoops covered with sheets of striped tarpaulin, which acted as a store for all the tools, and the coke brazier, that beacon of hope for the team’s survival. The hut, with its watchman in charge, would soon be organised. Scaffold-board seating was mounted on 10-gallon drums, filled with water. The men could enjoy a hot meal or a brew-up, and eat their sandwiches, which were kept wrapped in a tin on a makeshift table, under the eye of the watchman. This was their domain for the duration of the job.

The street where we lived was one of the earliest to be laid with tarmac, which proved much quieter when horsedrawn carts were delivering. Four side streets leading off this long street were our playground, as with no shops to supply they were rarely used by carters. When one of ‘our’ streets was being repaired it meant finding a new venue. We might be forced to trespass on other children’s play areas. Sometimes it meant we could play a wider range of games; the odd member of our gang who switched sides would not be welcomed back when our street had been modernised.

There were no mechanical hand tools in those days, just hammers, forks and shovels, with wheelbarrows to take away the spoil aboard the carts that brought the new filling. This would be granite stones about two to three inches in size. After it had been spread and levelled, a huge steamroller would arrive with a cheery hoot on its whistle, smoking and clanging, to flatten the staked-out pitch. At lunchtime, the men would return to the hut and stand around the blazing coke fire. Tea would be poured from a huge teapot. The mugs already had milk added from a large Cross Brand tin punctured with several holes to make pouring easier. Then a long toasting fork would appear, and large, thick slices of bread would be toasted, to be eaten without butter.

Cotton Street. This corner, where long baulk of timber has come off a cart before an audience of curious onlookers, was obliterated in 1945 by a V2 rocket.

Old Ford, where Levere Walk was. Iron railings became largely a forgotten feature of London’s finer squares and walks in the early months of the Second World War. Owens & Son was on the corner.

When work finished for the day, the tools would be cleaned and placed in the back of the hut, and the watchman would set out the heavy, round, iron base-plates with upright steel rods, on top of which were hooked the guardropes and paraffin lamps whose dim red glow warned road users of danger in the dark street. He would carefully fill the lamps, and then light his own, larger lantern, which gave him plenty of light to while away the night hours inside the hut. I struck up friendships with these lonely men. Some were not very old, a few ex-servicemen, disabled and unable to do the hard work they had been used to before the war. Now and then I would take a potato or two from Mother’s basket and we would bake them, sitting around the warm brazier, listening to stories until a shout from the front door summoned me to bed.

One street nearby was still made of the old, tarred, wooden blocks and, when news spread that this was being dug up, people appeared from all over with prams, barrows and sacks, eager for free firewood. The workmen put the blocks aside and a foreman saw that everyone got their fair share. Of course, there were young ‘entrepreneurs’ who, for a price, offered to sell the firewood to those without transport, or who were too infirm to collect it themselves. The ancient blocks split easily, but the layer of tar and rubble that had accumulated on top was highly combustible and, unless removed, would spit stones out of the fireplace and hit the folk sitting nearby. After burning a lot of these tarry blocks you used to get chimney fires, treating the neighbourhood to a cloud of smoky soot, and mothers would have to bring in their washing.

After the steamroller had done its stuff, a team would arrive to spread the steaming tar, sacks around their waists to protect their legs. I still remember the smell. Gravel would then be pressed on to the still-hot tar with a light hand-roller. Often, mothers with babes in arms would be seen talking to the tar-boilers. There was an old wives’ tale that the infants’ lungs would benefit from inhaling the fumes of the hot tar. I have often wondered if it worked: there was a lot of tuberculosis in those days.

The main road through Poplar was the East India Dock Road, and every now and again this would be held up in one direction while its large granite setts were being replaced; especially where these had split or subsided and cause a horse to stumble or a cartwheel to get stuck. This heavy stone-laying was an art and the workmen real craftsmen. Over the years I watched them work, as a young man and as an adult. I came to admire the hardworking men and women who were born and bred in Poplar.

A TRIP TO THE CITY

My mother had promised me a trip to the city. We planned it for weeks and I was looking forward to the great day, which came sooner than I anticipated. I was bathed in the morning! Actually, it was just a ‘top-and-tail’, not like the Friday night bath, for which we all got ready, one after another, and the first ones got the hot water and the dry towel.

Dressed in my Sunday suit, off we went on the Bloomsbury tram. A long walk through the streets to Holborn brought us to a great pair of iron gates that proclaimed St Bartholomew’s Hospital. It was the place you went to for all your ailments in the years before Great Ormond Street children’s hospital was opened. We sat on the wooden forms for a while until my name was called, and a pretty nurse took my hand and led me to a table with a white sheet on it. She placed a cover over my suit while Mum was shown a seat in the corner. A very tall man came and looked at me, smiled, opened my mouth and put into it, something that tasted like Gibbs’s tooth powder, that my sister used. There was a sharp pain, then the nurse stood me up and gave me a piece of white lint to hold over my mouth. Another nurse appeared, dressed in a dark blue uniform and a funny little hat, tied up with a bow. It reminded me of the little girl in the pram next door, but Mum did not seem so amused by what she was being told.

On the tram journey home, a big parcel beside her in a shopping bag on the floor, my mother muttered angrily to herself. I was glad of a cup of warm tea to ease my sore throat, which seemed to be swelling. Dad was busy with the daily task of shaving himself with an open razor in the small mirror beneath the gaslight. We watched in silence as he wiped the lather on the small squares of newspaper that I cut up in my spare time and threaded on a string, like the larger bundles in our outside toilet. Mother was catching up on her ironing, shoving the three flat irons back and forth on top of the hot kitchen stove, just inches from Dad’s legs.

My father stropped his Krups razor, before putting it carefully away in the correct day-case, one for each day of the week, and locked it away in a drawer. Then the story all came out: how they had taken out my tonsils, and Mother was insulted because the second nurse had said that I was poorly, and weren’t all six of her children, boys and girls, healthy? Father muttered in agreement and settled down to read the newspaper. The story was recounted in minute detail to every visitor, as well as to the poor woman from next door, who had only popped in to borrow something. In fact, although I was well cared-for, the youngest child of seven, I was not ‘healthy’: eighteen months into my life tragedy had struck. Boisterous brothers and sisters jumping about upstairs went through the old floorboards and brought down the ceiling of my mother’s bedroom, where I was sleeping. I was rushed to Poplar hospital, just 400 yards away. It was a miracle, they said, that I was still alive; but I developed meningitis, causing a fluid swelling compression of the brain. A London hospital surgeon was sent for and he decided to pierce my skull in seventeen places to drain off the fluid. The results would be uncertain: brain damage or physical impairment were possible. The actual outcome was a condition known as infantile paralysis which affected my right side, and still does, eighty-two years later. It proved very useful in 1921, when my family were able to obtain food vouchers from the council; and it kept me on the Home Front during the Blitz, of which more later.