4

The General Strike, Pubs &

Street Traders

As a nine-year-old schoolboy, I witnessed one of the most momentous events of East End history, the General Strike of 1926, which I recall so clearly three quarters of a century later. I lived within yards of the East India Dock Road, the main arterial road serving all of London’s sprawling docklands. Names such as East India, West India, Millwall, Surrey, Commercial, King George and Albert Docks have passed into legend or are inscribed on brave new housing developments. It was here that the strike began, fuelled by the anger and resentment of the working class people of Poplar and its neighbouring boroughs, and of the British miners and railwaymen’s unions, on 3 May. Pickets were placed on the docks in round-the-clock shifts, ensuring that no goods were dispatched from the dockside or unloaded from ships. Hospitals, schools and prisons were the only destinations to which goods were allowed to be delivered, supervised by a small army of men with armbands who barricaded the gates. From time to time, mounted police and, eventually, troops with armoured cars would emerge to escort convoys of essential goods through the shouting pickets.

The children were sent to school every day and so kept out of the way; after school, however, my brother and I ran errands for neighbours seeking news, as there were no newspapers or radio for a time. We lived about thirty yards from Poplar police station. Patrols would be inspected by the Sergeant in the yard at the back, where normally stray dogs destined for Battersea Dogs’ Home would be rounded up. Most of the policemen had relatives or neighbours among the pickets; theirs was a difficult job. They would be sent in to mop up behind the mounted squads from nearby Limehouse, who had quickly developed a reputation for putting down potential riots. The vast acreage of the docklands and travelling time between the docks and stables made it virtually impossible for so few police to control the situation. After they had left to change shifts and feed the horses, it was business as usual for the crowd. But there were few arrests; our local force could not afford to spend time writing reports and attending court for so little outcome.

Our local MP was George Lansbury, Independent Labour, who edited a workers’ paper. Unable to publish his broadsheet, he set up a printing press at his home in Bow Road and issued a daily bulletin to keep the strikers informed. One issue advised strikers and pickets to wear their war medals when confronting the police or soldiers, to remind them that they had also fought ‘for King and Country’. When the government brought in emergency powers, hundreds of special constables were recruited. Armed with long batons and striped police armbands, these ‘specials’ were not deployed in the East End, as few, probably, would have survived. The mob hated these ‘blacklegs’, as the strikebreakers were called. Some of the powers entrusted to the police were not made public, one being that if only two or three people were seen talking together, they could be told to break up and go home and arrested if they did not. This type of restriction caused a lot of hostility. My family and I witnessed some acts of brutality from our sitting room window; one man was pursued down the street by a policeman on horseback, who was striking him about the head with a baton. The neighbours all shouted to the policeman to leave him alone; the man, they knew, worked late at the hospital and was merely on his way home.

Soldiers on their way to the Royal Albert and King George Docks during the General Strike, May 1926. A contingent had already been detached at the East India Dock by the time this was taken.

Using armoured vehicles, strikebreakers moved food in convoy from the docks to the City during the General Strike of May 1926. In the background the Pavilion cinema is being extended to cope with the new fad for ‘talking pictures’.

Strikers stop a vehicle in Cotton Street at the back of the Poplar Pavilion where a film called The Iron Horse was showing. A single mounted policeman tries to keep order.

The Poplar rates dispute has become a forgotten bywater of history, but the numbers of protestors marching with banners to the High Court show that it was an all-too-real event for many people too poor to afford food in 1921.

Looking back now, I am astonished at the great division that the government created within the population at the time, a real sense of ‘Us’ and ‘Them’. Within three years of the Armistice of 1918 there was severe poverty among miners and the families of thousands of unemployed servicemen who had fought for a better country to live in. The Labour party was ineffectual in those days and easily branded as Trotskyists and troublemakers, especially in the wake of the Russian revolution and the murder of the Tsar and his family, news of which had taken a long time to come out and was still fresh in the minds of the better-off classes. Poplar knew real poverty – at one time, all the elected members of Poplar Borough Council were put in prison for spending rate money on feeding the poor. To save face, the Government told the council to treat the money as a loan, which was never repaid. The means the Government used to put down the strike in 1926 were notorious; university ‘freshers’, polo-playing cavalrymen, Lords and Ladies drove lorries and organised rest stations and food kitchens for the well-to-do volunteers, who were going to ‘show the dirty strikers’ who was boss. The thousands of strikebreakers running the buses and the railways or joining the police were oblivious to the plight of the miners and their families in Yorkshire and Durham who were, literally, starving. Yet, such was the miners’ spirit that they stayed locked-out for six months without even the meagre pay to which they might have been entitled.

Women councillors address the crowd from the balcony of the town hall in Newby Place, 1921. Protest mounted after the Government had the members of Poplar Council arrested for diverting rates money to a voucher scheme to feed the starving during the Depression. After six weeks of demonstrations the councillors were freed.

The four main railway companies were the GWR, LNER, LMS and Southern. They recruited volunteers who, after one day’s instruction, drove trains and operated signalboxes. There were casualties and breakdowns and a collision at Bishop’s Stortford that cost one man his life. Outside Newcastle, strikers removed a section of track and derailed the famous engine, the Flying Scotsman. A navy submarine was brought up the Thames so that its generator could power an important food refrigeration plant after the Battersea Power Station shut down. Warships were dispatched to docks around the country and naval ratings coerced into unloading and turning-round cargo ships that had been unable to berth at London. Half the time, the Trades Union Congress and its General Strike Council had no idea of the draconian measures being taken by the government, which was determined to prevent the ‘Revolution’ breaking out in Britain.

The dependence of Poplar on coal for its industry and home heating reflected that of the country as a whole. The miners’ strike was basically in the deep mines; coal seams close to the surface were now opened up and opencast mines appeared everywhere. Some of this low-grade fuel was dangerous, causing red-hot stones to fly out of the hearth and set fire to clothes and furnishings within range. Large dumps of this brown coal were set up and people encouraged to come and collect it for themselves. Boxes on wheels and even prams were used to cart the sacks away. A few enterprising deliverymen undercut the regular coalmen and sold half-hundredweight sacks of ‘nutty slack’ – mostly stones, dust and a lot of water if mined when wet. We never discovered if any of this fuel found its way into our local gasworks; we never seemed to run out of gas – anyway, our meter was always full of pennies. We could still buy coke – coal discarded from the retort houses after the gas had been extracted. But it was well into the following year of 1927 before we saw the return of the coalmen to our streets, with the best quality coal.

In its way, the General Strike, which lasted only nine days, showed the world that the working population of the UK had shown solidarity with the very poorest, despite government provocation, strikebreaking and harsh measures. During the six months’ ‘lockout’ that followed, working-class organisations in Poplar and elsewhere provided much financial and practical support to Britain’s miners, who as I write are now almost a vanished species.

DOWN THE PUB

Looking back through some old records I discovered sixty-one pubs in the Poplar area, including Limehouse and Millwall. These all bear the E14 district code, and many of them are described in this chapter, together with the names of the licensees and managers. They are, of course, all linked with various brewers, many of whose names survive, even if their owners have long departed. Watney, Coombe and Read; Truman Hanbury and Buxton; Mann Crossman and Pauline; Taylor Walker; Charrington’s, Ind Coope; Lovibonds. The latter, possibly the least familiar now, seems to have served the many off-licences dotted about the local streets. On delivery days the draymen, in their leather aprons, would lower the full barrels and pull up the empty ones on ropes, lowered into the cellars via the pavement-level doors, often spilling beer dregs over the pavement. They were jolly, tubby chaps, fond of a laugh and a joke with the passers-by, who either had to step over, or go round the ropes to get by. The delivery note was taken into the bar to be signed, and as a reward for their hard work, a couple of pints would be set up on the bar. After a number of deliveries, it must be said, the horses needed to know their way home at the end of the day.

Bottled beer started a trend and Worthington’s, Bass, India Pale and Newcastle Brown ales and, of course, Guinness, became a convenient way to go to the pub and get a few beers for your friends and family at home. To make an evening out on Saturday or Sunday, you dressed up. If you had cash in hand, you might stand a pal a drink if he was at the bar. Port and lemon was considered the ladies’ drink and not too likely to lead them into trouble. Pubs often had a pianist and a singalong helped to make a good evening. Local talent was most popular, and a familiar ballad played and sung with feeling would earn the virtuoso a pint from an appreciative member of the audience. Equally, it might result in a dousing in beer dregs for the player or the piano, from some likely lad who thought he was a laugh a minute.

The Aberfeldy Tavern, c. 1941. Some air raid damage can be seen at the corner of East India Dock Road and Aberfeldy Street, to where the pub eventually moved in 1946.

The Young Prince in Chrisp Street, on the corner of Southill Street, 1938. The happy regulars are assembled on the spot where the women sold clothes cheaply from a big heap piled on the road, and are awaiting the arrival of the charabanc to take them on an outing. Accordions were becoming increasingly popular.

The Resolute pub, Poplar High Street, 1936. The pub was rebuilt not long afterwards. One of the famous three-wheeled milk carts can be seen outside Hitchman’s Dairy on the right.

Jug and bottle bars, sometimes known as off-licences because you could not drink on the premises, did a steady midweek trade. There was no enforcement of any age limit when I fetched a jug of beer for my nan or grandad. Usually the money was handed over along with an empty bottle, there being useful ‘money-back’ on the returns. In the days before they started putting nuts out on the bar, there were small bowls of very salty shrimps; the salt was to encourage your thirst. For the children outside, peering in at the door, pubs sold biscuits, usually arrowroot, dry and tasteless. Later, along came the famous Smith’s Crisps, each bag containing a measure of salt screwed up in blue greaseproof paper. Nevertheless, the salt was always wet and it took a hard shake to get it all evenly distributed. Little packets of four biscuits interlaid with strong soft cheese were another favourite, made by Meredith & Drew. They cost twice as much as the arrowroot ones. The thick glasses beer was served in usually bore the name of the pub, but this small precaution did not stop the stock from diminishing, especially if the beer was taken to be drunk outside when there was someone you did not wish to meet at the bar.

The St Leonard’s Arms stood immediately opposite St Michael and All Angels’ Church. Dewberry Street is on the left, and Mercer was the publican from 1934 until 1952. The actor Terence Stamp mentions it in his autobiography, Stamp Album, as being a regular haunt of his grandmother.

The Volunteer, East India Dock Road. By the time this was taken in the 1960s much of the life of Poplar had gone, including the Grand Picture Palace and Karamel’s sweetshop. The pub itself was eventually demolished in the early 1990s.

The White Horse, Poplar High Street, 1926. The façade dates from about 1868 and the pub was rebuilt in 1929, to vanish completely in 2001. A tavern is believed to have stood on the site since the late 1600s and a very much older building houses Whale’s Ice Cream Powders to the right. On the far right can be seen a corner of the shop owned by a Chinese family who ran a ‘Puk-a-poo’, an illegal betting den.

The darts contest between the pubs in the locality was a moneyspinner for publicans. Some matches between invited teams went on well after closing time. The lights would go out around the bar, doors locked; they were officially and indisputably ‘closed’. No beer was supposed to be served after the bell went for ‘Time!’, and the last few rounds of the match would be played in subdued silence, rather than risk a visit from the Law. Winners and losers would be let out of the side door, a few at a time, to avoid causing a disturbance. Today’s jukeboxes and video games would have been a turn-off for the hardened drinkers of those days. But some piano-less pubs welcomed door buskers, who came round mostly in pairs. One would go in with a cap to catch a few pennies, while the other would keep a foot in the door and start singing, whistling or playing the spoons or bones. Though not all were appreciated, some of the singers had good voices. Young ladies, wives and occasionally a teenager would give a rendering of a popular song, sometimes in an Irish or Welsh accent.

Among the regular callers were the Salvation Army girls, the ‘Sally Ann’, who came in while the band played in the street outside. Selling a few copies of War Cry with a sweet smile usually brought them a few coins, sometimes a ‘bob’ (shilling) from the landlord; the paper was mostly left unread. When a full band was not available, an officer would play on a small, portable harmonium, accompanied by a few girls on tambourines. Setting up halfway between two pubs was most efficient.

Other pubs in Poplar were the weekly meeting-places of the working men’s fellowship societies, the Buffaloes, Oddfellows, the Loan Club and the HSA night. For these a room or bar was generally set aside. When I was running one such night I had to collect sixpence a week from each member, which insured their family against the cost of hospital treatment. The fishing clubs, and the pigeon fanciers all had their nights, as did the rowers in the pubs nearer the river. Sometimes clubs would contribute to Christmas funds for the children, to pay for a party, perhaps with a conjuror.

Temporary bar staff were always a problem in the days before the ‘upside-down’ optic dispensers and glasses with an official ‘plimsoll line’ came into use. Arguments frequently resulted from customers sensing short measure, especially when bought with a ‘mixer’ such as tonic or Vermouth. Another serious complaint was when the barman, on being offered a drink, would show a half-full glass and be happy to ‘have one later’. He would then put the money by the till and pocket it after the customer had gone. Tipsy customers, too, seldom queried their change, providing opportunities for sharp barmen.

The Bromley Hall Tavern, Brunswick Road, Bromley, with Zetland Street on the right. Built in 1902, the pub was demolished in 1971 to make way for the widening of the northern approach road to the Blackwall Tunnel. The Baptist Tabernacle stood on the opposite corner.

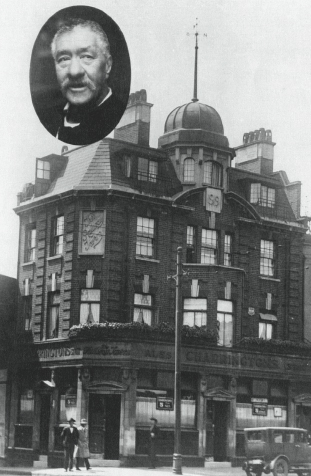

The Railway Tavern, West India Dock Road with, inset, landlord Charlie Brown. The uncrowned ‘King of Limehouse’, Charlie was a genuine East End legend, turning his pub into a museum with an astonishing collection of priceless Ming vases, Sèvres cabinets and other curios. The King of Spain once visited the pub incognito (introducing himself as ‘Alf’) to inspect the trophies, which took him two hours. Hugely wealthy, Charlie was a tireless worker on behalf of hundreds of charities. When he died in 1932 at the age of seventy-three, work in the docks stopped for his funeral and police had to force a way through the crowds who lined Burdett Road to Bow cemetery five deep.

As well as the landlord and his wife or whole family helping to run a well-organised pub, they could not do without the man they called the ‘potman’. He fulfilled many duties, including collecting up the empty glasses for washing from around the pub, outside and along the surrounding streets, yards and gardens. He always managed to find five or six that were not quite empty and would sup these on the way back. He also helped to bring up crates from the cellar at busy times. A good potman would always ask politely if a customer’s glass was empty before lifting it. A considerate, well-dressed potman was an asset to a pub and, if trusted, the landlord kept him on in regular employment and he never had to pay for his drink; like the drayman’s horse, he always found his way home.

STREET TRADERS

Mostly they would come to the front door, preceded by their cries, at regular times and on set days. Often the purchase would be only a penny or two, but they were always grateful for the regular custom and left with a cheery word before resuming their hawker’s cry. Retailing was more specialised then, a personal business. For the womenfolk tied to the home by endless chores, cleaning and cooking for the family, or caring for elderly relatives, their visits were a welcome break from the daily drudgery. They were the street vendors, or hawkers; now mostly vanished characters from the East London stage.

The Coal Man

Coal was delivered on carts in half-hundredweight sacks of ‘nuts’ or ‘best’: nuts for the kitchens, best in larger lumps for the open grates. London’s world-famous ‘fog’ of course arose from the sulphur smoke of thousands upon thousands of coal-burning chimneys: there was no central heating! When delivered, you immediately broke up the larger pieces for burning. The impact of the hammer scattered tiny fragments everywhere. These were shovelled up for banking the hot embers. Kings of the local coal merchants were Coe, Wilson and Grover. Regulars frequently had to see off, or put up with, less reputable freelance operators.

The staff of Cade’s coal depot, c. 1930. Joseph Cade & Co. were the reputable coal merchants in Longnor Road, Mile End. They successfully saw off competition during the Depression years from ‘freelance’ operators selling inferior coal.

The Milkmen

With their noisy, rattling cans hooked to the sides of their curious barrows, the milkmen did not need to call out as they made their way along the potholed streets. You got plenty of notice to fetch your empty can and replenish it from the big churn. Pushing and steering the three-wheeled barrows was an acquired skill; the front wheel was the turning axis and to negotiate a corner or an obstacle required a lot of strength. Hitchman’s from Kirby Street had the largest rounds; supplies were obtained direct from Culshaw’s dairy, where the cows stood, unnaturally clean in the spotless, whitewashed yard.

The Muffin Man

Yes, they really existed! This character of story and rhyme was for some reason seen and heard, mainly on dark winter or cold late autumn evenings. The clanging of his brass bell and his call as he waited at the street corner could be heard over a wide neighbourhood of households. His tray of muffins, dough buns covered in a nice, green felt, was balanced on his head. Customers would wait until the tray was lifted down and a stick put under it, to act as a leg. The muffins themselves would still be familiar today: you can buy them in supermarkets.

The Shrimp and Winkle Seller

This trader usually called around the streets on Sunday mornings. He never seemed to come later than 12.30, giving the impression that his produce was caught fresh with the morning tide. You would buy the shellfish, sometimes with a stick of celery or a bunch of watercress, which he sold separately, for tea. Whelks and mussels, too, were spread out on a large, white sheet on the floor of his horse-drawn cart. Your purchases would be ladled into a brown paper bag for weighing. He always called out ‘Gravesend shrimps!’ as you left. It was his calling card.

The Toffee Apple Man

Summer brought the toffee apple man, pushing a small, wooden box on wheels between two long shafts. The toffee apples were carefully laid out in rows, their sticks all pointing straight up. Toffee running down the apples would puddle on the bottom, leaving a squashed blob known as a ‘flat’. We searched for the biggest ‘flats’ we could find. Sometimes, the toffee apple man sold ‘flats’ by themselves, if he had run out of the soft eating apples; or he might just hand one to you. It was a job to keep the smaller apples on the stick after the first bite. The toffee stuck to your teeth and lips and even your nose, if you were too anxious to get to the middle.

The Grinders

Knife and scissors grinders were rarely seen in our street as so many people ground their own knives on the broken paving slabs they somehow acquired. When one did appear, my mother would get a price for sharpening the scissors, as father could never manage to get a good edge on those. The grinder would sit on his seat and operate a treadle attached by a leather belt to the spindle in the centre of the grinding wheel. Now and then, he would pour a little water over the stone from a small can that swung under the barrow. Sparks flew, then a wipe with a rag and the article would be brought to the door, where the keenness of the edge would be demonstrated on a thick pad of newsprint.

Rag and Bone Men

In later years these became general scrap dealers; however, their original stock in trade was old clothing and animal bones, which had a variety of uses. Nothing was wasted; recycling is not a modern invention. At the familiar cry you looked to see who it was, as several of the street hawkers gave good prices. In our street they were on to a loser, however, as we had a resident shop, Hyman’s, where most of our rags and bones went, although my mother always complained of being short-changed. Now and then a barrow man would present you with a windmill, gaily fluttering in the wind, instead of cash; a skipping rope, or even a live newt or goldfish.

This team of coopers, photographed in the 1930s, worked for John William Sayers of Ropery Street, Bow. The firm was kept busy between its foundation in 1881 and 1957, making and repairing beer barrels for all the breweries in the neighbourhood.

Door Knocker Painters

This ‘little man’ had few tools to carry: two small tins on a wooden frame, one holding brushes, the other black lead paint, which he was continually having to stir. Most people in those poor neighbourhoods took a fierce pride in their front doors and steps, the women on their hands and knees, whitewashing the grimy stonework and a half-circle of pavement around. Woe betide anyone who walked on the newly painted pavement! The door knocker painter would attach a card to the door, warning of wet paint for the next 24 hours. At Number 20 we had a brass letterbox, which was properly polished every week by my dad.

The Ice Cream Man

The first ice cream man who ever came to our street was an Italian. Despite his rudimentary grasp of English he knew how many pennies made a shilling. His ice cream was a solid vanilla block wrapped in what looked like blotting paper, sold from a barrow. The call then was ‘Assenheim’s’, this being the not-very catchy brand sold at the time. It soon went out of fashion, to be replaced by Wall’s. The little three-wheeled carts had the famous slogan: ‘Stop me and buy one!’. Ices, vanilla blocks and tubs came out of cold boxes that steamed when the lid was lifted. A man with a horse and cart occasionally came and people would bring out their own containers for him to scoop the ice cream into from a block, topped off with a wafer.

Posy Sellers

On weekend evenings at the height of summer, two or three young ladies would appear in the High Street, between twelve and fifteen years of age. They were selling small bud roses wrapped in silver paper and finished off with a fine sprig of fern. The roses gave off a lovely perfume. They were kept fresh with a sprinkle of water from a lemonade bottle tucked away in a basket on the pavement. Girlfriends would accept these small tokens gladly and, now and then, the lads would sport them in their buttonholes.

Chimneysweeps

The chimneysweeps did a good trade in Poplar, the brush being the only method they used in the 1920s and ’30s. The brush had to appear out of the top of the chimney pot and one of the family had to go outside to make sure it had come out. On dry days, the soot flew everywhere in the house, and piles of ground salt would be kept ready – this made it easier to sweep up the soot. In addition to the many fires caused by burning tarry blocks and impure coal, which caused the soot to build up rapidly inside the flue, chimneys would be deliberately set alight to save the cost of a sweep. They would be hurriedly put out by the guilty occupant, hopefully before a neighbour raised the alarm and the fire brigade appeared.

Not just a humble chimneysweep, Thomas Brooks was Mayor of Bethnal Green in 1931/2 and a Councillor for thirty-four years. He began sweeping chimneys at the age of twelve, and it was said of his election to mayor that he was ‘well sooted’ to the task. (© Hulton-Getty Collection)

Dockyard Tea ‘Boys’

Near the docks, it was a regular sight to see a man carrying a stick, about three feet long. This had nails sticking out and six or seven mugs swinging from them, filled with steaming tea from the local café. The café did a very good trade with the dockers and usually stopped serving when the tea boy appeared. There was quite a distance to walk back to the dockside with the mugs of tea, carrying any other purchases the men had requested. Dock tea runs started at 7.30 in the morning and went on until 10.00. One tea boy told me he had never done any dock work: he had been taken on for this job alone. I never saw them work in the afternoons.

Pub Buskers

We lived next-door-but-one to a public house and, as there was virtually no other sound in our living room apart from conversation and the occasional argument, we could hear clearly the noises coming from there. In the quiet of the night we would hear singing, and know that the saloon bar door had been rudely pushed open by a pair of buskers. One kept his boot in the door while the other gave a rendering of a popular song of the day, before passing the hat. Then, we might hear the sound of a pair of spoons being hammered, back to back, up and down the player’s body to accompany the singing, which varied in quality. ‘Martha’, ‘Danny Boy’ and ‘Ramona, I hear the mission bells above’ were the usual fare. Some nights more than one pair of buskers would come along, much to the annoyance of the publican.

Street Buskers

There were many entertainers in the streets. Some would hire a barrel organ and push it all the way to Poplar. The operator would keep cranking the handle, and the barrel organ would play three or four songs while a colleague passed the hat around, collecting from passers-by. Sometimes a third man would tap-dance or sing, dressed as a woman, in a high-pitched voice to amuse the children. Other organ grinders kept a monkey on a chain that would dance or cleverly hold out the hat for people to toss coins into. Sometimes there would be a duet, with a trumpet and piano-accordion. These were becoming the vogue, replacing the old concertina, which was associated with out-of-work seamen and the Salvation Army. There were solo singers, too, the men loud and deep-throated, turning their heads from side to side to let the sound radiate far down the streets around. Arthur Tracy, the famous street singer, copied this technique for the music halls he performed in.

The Side Street ‘Unofficial’ Traders

They stood at the top of a street where it joined the market, keeping a wary eye out for the market inspectors, ready to move on hurriedly at the sight of a peaked cap. Regular shady traders were the silk stocking men who worked from a battered suitcase down by their feet. Their cry as they held up a perfect stocking with their hand inside was ‘Every pair bears inspection!’ but it sometimes didn’t, when you opened up the bag hopefully containing the colour you had asked for. You might have a pair that did not match, or that was laddered before the lady even put them on. By the time you returned, the silk stocking man would be long gone, perhaps to the next market if he had lots of goods to shift.

The Round Elastic Man

This highly specialised salesman was another ‘unofficial’ trader. He wandered up and down the market crying ‘Best round elastic!’ Actually what he sold was not round at all but more like tape, white and in various widths. Where it went was ‘round’ the leg or waist! Quite a lot of elastic was used by the poor people in those days, for socks, knickers and tied under the chin to keep a child’s hat or bonnet on, to mention only a few uses. The elastic was sold by the foot or yard and measured with the 18-inch rule he kept hidden inside his coat.

The Horseradish and Mint Man

My dear friend George White was the mainstay of his family, one of the nicest and most hardworking men I ever had the pleasure of meeting. They were very poor, his mother was widowed, and George kept an allotment near the railway station, where he grew horseradishes and bushes of mint. He ground up the horseradish roots on a little board that hung from a string round his neck, packing the portions into little white bags. An essential accompaniment to the Roast Beef of Old England, his horseradish was sold by him from a pitch as near as he could get to the butcher’s. When the season arrived for spring lamb, he sold sprigs of mint to make mint sauce. Rain or shine, he was always there, sometimes drenched, and he would help any trader in the market, especially if a few extra shillings could come his way after his stock had sold out.

The Razor Blade Seller

After safety razors arrived, you bought replacement blades in packets of five, wrapped in greaseproof paper. Gillette, Seven o’Clock and Ever Ready were the most popular brands. The razor blade seller was another ‘unofficial’ trader who did not need to rent a stall, as a cardboard box held in his hand contained six packets of blades. He would stand as far away as possible from the chemist or the barber’s shop, and his prices were coppers below those regular suppliers, with their overheads. Where his supplies came from, nobody knew. Suspicions grew, however, when he ‘could not get any more’ at the price he had been offering!

The Salt Seller

This chap had such a small barrow, it would have been a crime for the market inspectors to have charged him anything for a pitch. Strategically positioned near my friend the pot herb lady, in case of shoppers planning a stew, he had a block of salt perched on a cart with four small pram wheels, to which was attached a rusty saw. His cry was: ‘Don’t forget your salt, ma’, an idea later borrowed by the advertising agency for Rowntrees Fruit Gums. He would saw off a portion and wrap it in a piece of newsprint; two if it was raining. My mother gave us boys the job of pulverising the blocks of salt into a jam jar, with a finer grinding for the salt cellar on the table, whose tiny spoon was always getting lost.

The Lamplighter

When we played on the streets as children, even after dark, no one thought of us as being in danger from child molesters or hit-and-run drivers. Often a door would open and a parent would call out, but the sound of shouting and laughter reassured them you were out there somewhere. As it got darker, up would come the lamplighter on his bike, steering with one hand as he balanced with the other, the long ignition pole which he carried on his shoulder. The top of the pole engaged with a lever on the lamp standard and opened the gas valve; a lighted wick completed the job, bathing the dark streets in pools of wan light so that we could play outside for a few hours longer. I often watched him light the lamps, but I never saw him turn them off – I was still fast asleep.

The Cat Meat Man

I have mentioned him earlier. He was very popular and had a shop in St Leonard’s Road and a long round throughout Poplar. He carried a very large basket, inside were the cut-up cubes of (mostly) horsemeat and a bundle of sharp-pointed skewers, which he would thrust through a dozen or so pieces of meat at a time, calling out ‘Cat meat!’. If there was nobody in, he would leave the skewers under the door knocker, out of reach of the interested neighbourhood cats. It might remain there for several hours before anyone came home. I never saw him wearing a tie or scarf, just a narrow, white collar, stained with grease.

The Indian Sweet Man

When this gentleman first appeared on our streets he was viewed with a certain amount of trepidation. But he was always polite and smiling and, of course, he was especially nice to us younger customers, who would nervously hang back before handing over our coppers, to receive the twirled-up spun sugar on a stick that all children today would recognise as candy-floss. To contain this mountain of joy he had a tin box, about three feet square, slung around his shoulder on a wide leather strap. After serving the children he would move on a few yards, tinkling a little brass bell. He would leave us flapping away at the wasps that swarmed in summer, attracted by the sugary smell. Strangely, they never seemed to go after the Indian sweet man.

The Newsboys

Young lads who could not find work on leaving school often became newsboys. Not the usual ones you imagine, getting up early in the morning to deliver papers and magazines on their rounds, these older lads were in a class of their own. At about eleven each morning they would start out from the paper shop with a big bundle under their arms, calling out ‘Mid-day!’ or ‘Classified!’ as they dashed about. The only time they stopped briefly was when someone wanted to buy a paper. Their second round was between five and six in the evening, when the cries changed to ‘Final!’ ‘All the results!’ and ‘Prices’, advertising the editions containing the afternoon’s racing results, and the closing prices on the London Stock Exchange for the homegoing City workers.

The horse vet, seen in his surgery doorway at 773 Commercial Road, Limehouse, with his tough-looking assistants. The job often involved putting down horses injured in traffic accidents. He would regularly attend on horseback as it was quicker than using the lorry.

The Horse Vet

I spent all my young days watching horses and carts of all kinds, laden and unladen, passing by our house. You sometimes came across the horrible scene of a horse having to be put out of its misery. One bolted straight through a large glass shopfront and severely injured itself. People tried to help the poor driver free the horse from its twisted reins and harness, and covered it with sacks and mats. When the vet rode up on horseback, after what seemed like hours, he put a gun to its head and shot it. The crowd drifted away, and neighbours came with buckets of hot water and carbolic to wash down the pavement. The horse was carted away meanwhile to the slaughterhouse, to be turned into cat meat, no doubt. Such incidents stay in your memory.

The Blacksmith

There were two local smiths who were often called away from their anvils and forges to attend to a horse with a lost or bent shoe. Drivers cared for their animals, mostly, they were their livelihood, and they would not want to move without the horse being properly shod, so the smithy would have to go to them. Sometimes, their skills, brawn and tools would be needed for other jobs: iron bending, straightening or hammering home some part that had become attached or detached from a vehicle. Sometimes the vehicle had to be lifted up while they got underneath. I was fascinated by these ‘men of steel’, either in their yards or in our streets.

Glaziers

We had two of these tradesmen, riding along the street on their three-wheeled bikes with a wooden box slung on the back. Small sheets of glass were carefully wrapped in felt, and the boxes packed with tins of putty, tacks and nails and, of course, a small hammer. A brush pan and bags to take away the broken glass completed their toolkit. They reminded me a lot of the Charlie Chaplin film where Jackie Coogan as the young lad was sent round the streets with his catapult to break the windows while the tramp, as his father, came along to mend them. Our men had no ladder, so they had to go inside the houses and sit on the windowsills to complete their work.

The Blind Match Seller

You may be old enough to remember these tragic survivors on the streets of London, but unless you are as old as I am, you will almost certainly have no impression of how terribly young they were in those early days. Usually in their twenties or early thirties, they would tap their way about, unless accompanied, or stand on the corner with a tray of matches, calling out ‘Camp!’ or ‘Bryant & May’s!’, being the rival brands of matches. The white tray would contain about six boxes, with a space left for the poorer women shoppers, mostly, to leave a few coppers, their only income. Often, the matches were not needed or even taken. A card on the tray and perhaps a campaign medal would give a stark reminder of where their sight had been given for their country: Mons, Ypres, the Somme. Blind charities like St Dunstan’s or Lord Roberts’s Workshops were in their infancy, but did wonderful work in later years.

Hot Chestnuts

These two words bring back the inviting smells, and the warmth and friendliness of the hot chestnut sellers who stood vigil on cold nights from mid-September until the Christmas season. The nicer one stood at the top of Chrisp Street, on the daytime site of the Burgess fruit stall. He would do his best trade on weekend evenings, catching the passers-by in the East India Dock Road. Steadily stoking his well-stocked brazier of coke, chatting to the customers, the operation of cutting the nuts with a cross was performed with great dexterity, the nuts placed on the red-hot iron sheet to roast. Every now and then he would flip them to do the other side, then quickly shovel some for a customer off the top of the heap into a small, white paper bag. It was not only chestnuts; the back of the stove had a box containing six well-pricked potatoes, little puffs of steam signifying readiness. He would cut them for you, or hand you a drum of salt if you wanted to eat on the premises. As a small boy, I remember him making up hot cordial drinks from the kettle that always stood on the side of the chestnut griddle. There was a choice of blackcurrant, peppermint or sarsaparilla. We asked him hundreds of questions, this friendly little man, but he always knew the answers.

Street buskers collect their barrel organs from Faccini’s Piano Hire warehouse in Ernest Street, Stepney, early 1920s. (© Topham Picture Library)

French Onion Sellers

They came between the months of May and September, an invasion of Frenchmen on heavy, black Peugeot bicycles. They wore berets, and striped Breton shirts, and had long strings of large, juicy onions slung over their shoulder, of a size that, with Bulldog perversity, we called ‘Spanish’. In point of fact, we had three greengrocers already in the street they patrolled, and within about 50 yards another six vegetable stalls in Chrisp Street market! All, I am sure, sold identical onions, probably cheaper. Sometimes you would see a conclave of three or four, all with those thin, Clark Gable moustaches. One young housewife near us would stand at the door and engage them in conversation, probably improving their English. An onion would be detached from a string, and the man would pedal away. They never called out, just stood on the corner looking around, hoping someone would accost them. I wonder where, really, they came from? Why? Who paid their fares? How many onions did they have to sell to make any money at all?

The local dust cart, ready to start work.

The Rope Mat Mender

Of the thousands of terraced houses in Poplar, few had carpets or lino in their passageways: just bare boards, or now and again a strip of oilcloth along those long, narrow confines. The family would enter straight from the street, bringing with them all the dust and grime, so very often, rope (nowadays known as coir) mats would be put down to trap the worst of it. These quickly became worn and frayed, and the mender man would come round and look up each passageway and point out those that would benefit from his big needle and tough string thread. A deal agreed, he would sit on your doorstep and quickly save you the cost of a new mat, often joining together pieces of those that were otherwise past repairing. The things our mums had to do to save money!

Dustmen

The poor horse pulling the heavy, open dust cart was always surrounded by a swarm of flies. As the cart trundled by, the loose canvas flaps would be thrown aside, the battered, flimsy bins lifted from the kerbside and banged against the inside to empty them. If still about, the lids seldom fitted well after such treatment. We had to carry our dustbin, with the house number painted on it, all the way round from the backyard. With so little packaging, the rubbish consisted mainly of materials that could not be recycled: dust, ash and unburnable cinders from the kitchen and the scullery copper, which burned continuously, summer and winter. Nothing that could be used for fuel was thrown away. Even tea leaves were used to bank the fire in winter so that hot water and breakfast could be ready for the early workers. Our dustman was always polite and gave us a knock the week before Christmas. He was one of the few who received a Christmas box, as it used to be known.

The Vinegar Man

A dear old man who came to our turning every week, he was so tiny that I am sure even the poorest people of the streets felt sorry for him as he pushed his barrow along. On this was mounted a wooden barrel with a tap at the bottom, and below this hung a small Nestlé milk tin to catch the drips. You brought an empty, clear-glass lemonade bottle, with the screw stopper, and he would fill it, pouring a tankard measure through a funnel. You could see you were getting full measure. The strong malt vinegar seemed to have twice the flavour of that which you liberally sprinkled over your bag of chips at the fish shop. Their watered-down version stood next to the large salt shakers on the counter, to which you helped yourself liberally for free before the meal was wrapped in its white paper and taken home.

The Carbolic and Firewood Man

In the warm weather, when the gullies, drains and roads had no rainwater to flush them, this man did a roaring trade. The smells of the factories seemed to fill the air; the gutters were choked with dust, dog and horse droppings; backyard toilets developed a noxious odour. He would fill your R. White’s or Western lemonade bottle straight from the barrel on his barrow, while publicans would bring a small container and douse their backyard public toilets liberally with the strong, white disinfectant, leaving white puddles lying around for days. To walk through them was to sanitise the soles of your boots for life. The bundles of chopped firewood, tied with tarred string, were brought into the house and carefully stacked on a shelf in the hallway, to be used only when absolutely necessary. The combined smells of carbolic and tar lingered for years.

Kate the Washerwoman

On a Monday morning Kate could be seen pushing a flat-top trolley like a big pram along the street, knocking at the doors of her regulars. She was only about four feet eight tall and sometimes was hardly visible above the pile of washing she had collected. This she took to the public baths, which were equipped with tubs, hot water and tables to lay out and check the items taken in for washing. There were wringers, too – but not enough: you could wait your turn, sometimes for quite a while. This caused hard feelings among the women, always pressed for time. Otherwise, they would exchange the news and gossip of the past week over the soapsuds and the washboards. I never found out how Kate knew what washing belonged to which customer, or what the rate of pay was for her services, but she was a great help to busy mothers and the ones who were expecting babies in particular came to rely on her a lot.

The Gas Meter Man

Once a month my mother’s daily routine would be interrupted by news from along the street that the gasman was coming to empty the meter. I stood or sat on the passage floor and watched the ritual of the meter box being emptied on to the mat. The pennies were piled into stacks of twelve to a shilling, to make up five shillings, which would then be put in a blue coin bag and several of these, if the meter was full, went into one large Gladstone bag. The rebate was always welcome, I never knew my mum to question the amount: it was all written up in his book and then the meter man would move on to the next house in the street. Before closing time at 3.30 he had to deposit his heavy bag at the bank; anything he took later would accompany him home, to be banked in the morning. Saving gas was obligatory in our house, all our evening activities were concentrated around the one gas mantle, which made a good target for missiles and sometimes got broken, with many denials. We always went to bed by candlelight but later there was a gas bracket in the bedroom, with an eerie flame like a Bunsen burner, which the oldest boy was trusted to light.

The Gypsy Ladies

When I was a small boy, in my storybooks gypsy ladies sat around a fire with a cauldron suspended on three stakes, cooking a meal. It was a surprise then when four gypsy ladies wearing colourful headscarves alighted from the Number 65 tram clutching one small baby and several large baskets. Descending on Ida Street, where we lived, they split up, two to each side of the street, and began knocking. We were instructed to close the door if they were on the step as the washing was hung in the passageway and we did not trust them. Mother would take a copper or two – never her purse – and inspect the basket of wares. Skeins of black or grey darning wool, small packets of needles, cards of white linen, coated tin buttons of various sizes: twopence was usually enough to purchase something. If nothing took Mum’s fancy, sprigs of ‘lucky white heather’ would be produced amid much wheedling. Mum never did succumb to their entreaties to cross their palms with silver and have her future told; she reckoned that had been settled when she married my father. Dad said the Gypsies parked their caravans on Wanstead Flats, where the men could be seen cutting wood to make clothes pegs.

The Mussel Man

A big man wearing a blue fisherman’s jersey summer and winter used to stand on the corner of Grundy Street and call ‘Mussels!’ or sometimes ‘Fresh Belgian mussels!’. He sold them by the quart pot, which would be emptied into a strong brown paper bag. The mussels, which were imported daily from Ostend, were still wet from his bucket. This gave them a fresh, shiny appearance while he toured the streets. We only tried them once when my new brother-in-law Arthur, who was a Poplar policeman, brought home a big bag and cooked them himself for his tea, much to the disgust of my sister. I think he had acquired a taste for them while serving in Belgium during the First World War – more likely than in Dulwich, where he was born and brought up.

The Travelling Roundabout Man

The clanging of a handbell brought the youngest children rushing in excitement to their doors. Outside was a horse and cart with a red, white and blue painted roundabout, revolving slowly. This was worked by the man turning a large handwheel beneath the cart. On the cart was a box containing dozens of glass and stone jam jars. One jar was the ‘fare’ for a turn on the eight-seater roundabout, which creaked at every turn while the poor horse stood still, the cart kept stationary by means of a chain running through the spokes of the wheels. The mums and aunts stood by, ready to lift off the children when their turn ended. I wonder what that man did with all those jars, to earn a crust?

Silk Scarves and Gaudy Ties

Every spring a small stream of Indian gentlemen would issue from a disused shop in Grundy Street, each carring a small suitcase. Over their shoulders would be draped a motley selection of brightly coloured scarves and ties. Opened on your doorstep, should you show interest, the cases proved to be crammed with more gaudy neckware. These salesmen all seemed identical, their black hair shining with what looked like Brilliantine. In the evening they all returned to the shop, never hurrying, but walking with a sort of shuffle. In the late evening they would reappear in small groups and sit on the pavement, either getting fresh air or just waiting to go to bed. They had a manager in charge of the team, who allocated them an area, supplied the goods and deducted the money for board and lodgings. They were familiar with British money and never gave discounts.

The Baker’s Boy

We always called him the baker’s boy but in reality he was in his forties. He sometimes had a real boy with him, who would knock each side of the street to let the mothers know he had arrived. Inside the four-wheeled cart was a crowd of newly baked loaves: cottage loaves, split tins, bloomers, sandwich tins, small brown loaves and crusty rolls. Some of the rolls had been too long in the oven and were burned black. Underneath the cart was a long drawer concealing scones, doughnuts, jam tarts and both types of flour you could get then, plain and self-raising! Now and again, yesterday’s loaves would be available cheaply to a good customer. They made a good bread pudding. The bakers used out-of-time bread themselves to produce what we called ‘mince’, small slabs of a bread pudding cake with sultanas and raisins, baked on the outside with a layer of flaky pastry, very filling. More so than the fairy cake sponges with a little piece of cherry stuck on top. Your penny had to go a long way to fill your stomach.

The Tally Men

No list of Poplar street characters would be complete without the tally men, those hardworking doorstep credit brokers. Two were very active in our area. One was Mr Anderson, who owned a shop in Abbots Road. He and his wife called round regularly on Fridays and Saturdays and collected cash from their customers. Often, the smallest member of the family would open the door and announce that ‘mother says she is out’, and battle would commence. The other was a green young salesman from Blundell’s in City Road. He booked orders and would take a small deposit, perhaps for a pair of blankets or some sheets and pillowcases. It was all on trust; suing for payment was nigh on impossible and too expensive. The large parcel would arrive from the well-known carriers, Carter Paterson, and would be signed for by ‘John Bull’, ‘L. Kitchener’ or ‘W.G. Grace’. The carrier never queried the signature. The goods would then be unwrapped and taken next day to the pawnshop. Blundell’s could never prove it had been delivered, as the grumbling householder would complain when the young man returned. They would demand a refund of their deposit, saying that they had changed their minds. The final outcome of these tricks would be that the pawn ticket was offered around the district at a reduced rate, to anyone who wanted a nice new pair of blankets or some bedlinen.

The fair visits Poplar Recreation Ground, 1919.