5

The Blitz

Many readers now in their sixties and older will bear witness to the events that occurred in the early days of the bombing of East London; the lucky escapes, the devastation, the tragedies – not forgetting the many heroic deeds that Poplar and East End people performed as wardens, heavy rescue, fire and ambulance service workers, or just as good neighbours. A number of their stories and pictures are to be found in My East End, by Anita Dobson. In my story, though, I have moved on years and advanced my position in the offices of Fraser and Fraser Ltd, whom I joined in 1937.

The early months of the war until the spring of 1940 were a time known as the Phoney War. Nothing much happened – but that did not stop us from mounting a large Daily Express battle map on a sheet of cardboard. Two sets of coloured pins were moved back and forth daily, after consulting newspapers and listening to the BBC news. Once we had to start again, after the office cleaners erased the battlefront by tidying up the pins. I was called up and required to attend a medical in Ilford, but graded C3, which kept me out of the services. Our works and office staff got fewer and it was becoming hard to find suitable replacements.

The declaration of a war in which my disability prevented me from serving at the Front speeded my rise to a higher position. Many of the bosses had moved their homes and families well out of bombing range, to nice places like Tring and Bromley. This meant I was in charge of a number of departments and was always on call, having evacuated my wife and two young girls to the Cotswolds and chosen to stay and live all week in the basement of the offices. For several years, the stationery room became my bedroom and wardrobe.

Our factory was situated alongside the District Line railway, and at the bottom of the yard was a wharf on the River Lea, from where we got our water supply. The railway line went over the river and then across the Regent’s Canal. On the other side of the railway station, which was next to our building, was a large gasworks with two huge gasometers and next to this, on the other side of our building, was St Andrew’s Hospital. The road outside led to Bow Bridge and then on to the Blackwall Tunnel. Strategically speaking, my temporary home was smack bang in the middle of Bomber’s Paradise, and the noise at times was very frightening. Somehow, I emerged unscathed.

The RAF ordered underground petrol storage tanks from us and dug holes all over the Home Counties to conceal them in. We also made decontamination tanks and equipment for the Ministry. As the demands of the war gathered momentum, orders were flooding in from the Drawing Office with lists of items required down to the smallest nut and bolt, and our stocks of steel were soon exhausted. Yet we had to replace it or lose business to our competitors – not everything had changed.

For the Army, we made dozens of armour-plated cabs to protect the drivers of troop carriers; while from the Admiralty we had requests for mooring buoys, large, flat floating tanks; and from Trinity House, orders for various types of marker buoys to mark both shipping lanes and the increasing number of dangerous wrecks around our shores. Each order had to be accompanied by the appropriate certificates, specifying the weight of steel and our place in the priority ordering queue. My job was to obtain these supplies for our workforce, many of whom had never before even seen the new lines they were designing and making.

At the outbreak of war there were quite a few shops near our office, tobacconists and confectioners, but gradually they closed down with the introduction of rationing. There was also a pawnshop, but the war meant plenty of work was available and earning a living became easier, legal or otherwise. Spivs flourished in the East End, forming a Mafia of their own.

DAD’S ARMY

In the spring of 1940, the rapid advance of the German Blitzkrieg caused a panic rush to join the Home Guard. Six of our men joined, and the headquarters in Bow Road was the factory of Ben Williams, who had a contract making uniforms for all the services, including the police. We had the best turned-out guards in the country! Fire guards, too, were organised, and a small bedroom-cum-canteen was set up for the four who would be on duty every night. Although we were paid ten shillings a night there were always defaulters, and I became a regular stand-in as I had to be in the building on a more-or-less permanent basis. It was agreed that we would spend our nights below ground, not only to protect ourselves against Nazi bombs, but against the fall-out from our own ack-ack – a wise precaution, as it happened. HMS Kelly and HMS Cossack were in dry dock, commanded by Mountbatten. One night, they opened fire on the bombers heading back from having another go at the Thames bridges. We heard the guns getting louder, then suddenly a shell landed, right in the middle of a delivery of steel pressings for a consignment of 500-gallon tanks for the Air Ministry. Fortunately the six-feet-high stack of metal stopped the sideways blast. As the manager responsible for reporting it, I could hardly classify this as enemy bomb damage: we had the end cap of the shell with the WD arrow mark still on it. The recoil of the gun knocked the ship off its props and it developed a 20-degree list. Someone must have been torn off a strip!

Headquartered at the factory of Ben Williams, uniform-maker in Bow Road, we had the best turned-out Home Guard unit in the country.

During the raids, I would emerge like a mole above ground and confer with our night watchman, to see if there was any damage to the buildings, which he guarded from his concrete hut. The windows were protected with plywood boards, which he put up every evening before the sirens went. His dog Sheila slept under the table in a wooden box with a blanket in it. He was without doubt one of the bravest men I have ever met, and a really wonderful worker, having been taken on after the First World War on his release from a German PoW camp. After we had exchanged information, he would walk home to Forest Gate, five miles away, and the following night, tell me everything he had seen along the way. Meanwhile, my bosses would telephone from their suburban hideaways to enquire if there had been any bomb damage to the factory, if any money had come in, any new orders taken or whether the War Office inspectors had been to check the previous orders, so that they could be released.

After a heavy raid one night, I answered the telephone to an anxious manager from the local Sanitas factory. He asked if I could send over some men with corrugated iron sheets to seal off the works, as a bomb blast had shattered the windows and blown in the doors. A team were duly dispatched to the site about two miles away and, in the evening, returned and gave me a detailed report of what they had done and the materials they had used for the job. Two days later, a man came into the office asking for me. He was from Sanitas, and I quickly explained that I had not yet made up the account and hoped that nothing was wrong with the job. He admitted that we had made a very good job and would I thank the men, and ask them if they had seen six half-hundredweight boxes of soap, about three feet square? These were ready to be dispatched to the Army but had disappeared. I explained that our lorries were of the flatbed type, with no sides or covers, so nothing of that size could have been removed by my men. After he had gone, one of the office boys asked me if the man was from the CID; had he asked me for the names and addresses of the men I had sent to the factory, and had he asked me about soap? I told him off for listening in on my conversation.

The author, fourth from the right, centre, with a basket to collect up human body parts for identification and burial. It was a pitiful sight watching the homeless people scrabbling through the rubble for their few personal possessions.

Well, that night I had soap on my mind and in the morning, went to see the gang foreman to ask him what he knew about it. He immediately assured me that my share was underneath the bench in the garage. I guess that, if I had not asked, he would not have volunteered this news.

I took some of the soap home and gave it to Lucy, my mother-in-law, who was living with me at the time. She was highly pleased, soap being in short supply; at least, until she tried to use it, when her expression of pleasure changed to a scowl. The soap was hard as stone and, even with boiling water, she could not get it to lather. The ‘perks of the job’ were reluctantly consigned to the dustbin; our loss, though, was probably the Army’s gain.

Londoners bed down for another night on the platform at Elephant & Castle underground station. Over 200 died in an escalator panic at Bethnal Green.

A remarkable news photograph of buildings collapsing in Queen Victoria Street at the height of the Blitz. The road was blocked and rescue workers had to go for miles around other bomb damage to get back to their depot.

SHELTERS

On a rare visit home to Dagenham I found Lucy distraught. The underground shelter that we had taken so much trouble to dig had filled with water almost to ground level. At that time, the firm obtained about five tons of cement and several thousand bricks and this was issued to the work force to protect their families. I mentioned the problem of the Anderson shelter to my boss, Mr Tawse, and between us, we designed an elaborate, reinforced steel shelter to be erected above ground. This protected my family through the years of near-misses and became a play cabin for the children after the war. But I could not keep in touch with the office from there. One day, a senior Naval Officer visited us to press for a large order of paravanes, a device towed by minesweepers, and I mentioned my problem to him. Within three days a pole was erected and our house became the only one in the street to have a telephone! The officer was later appointed to command a destroyer.

Not every household had a garden suitable for an Anderson shelter; such dwellings were issued instead with a Morrison shelter, a sturdy, table-like construction made of steel, capable of taking two or three people at a pinch, for indoor use. Hundreds of street shelters, too, were constructed of brick, topped with a reinforced concrete roof. They had strong steel doors and, in front, a blast wall to prevent a near-miss from buckling the door. Several of these shelters were built for the people who lived in the Poplar tenements known as ‘the buildings’, four-storey blocks of flats between the Blackwall Tunnel and Cotton Street, and several others on Mannisty Street. Many of the people living there took shelter in the tunnel at night, sleeping sometimes on the roadway when it was closed during raids. The tunnel had to be sealed off, as a direct hit could have caused serious flooding. Street wardens and sometimes even the police were on hand to keep the peace, in case of territorial squabbles. The crowded tenements in Whitechapel and Aldgate were occupied by the large Jewish community, overlooking their workshops and market stalls. They suffered tremendous damage and many personal tragedies. The children had been evacuated, but elderly and housebound occupants were trapped in the upper floors. Taff, my brother-in-law, was on Heavy Rescue duty and told me of the numbers of people he and his squad tried to save.

The author’s brother-in-law, Taff Eardley, is the lower figure on the ladder. Their job was to guide a steel hawser around the brickwork so that the building frontage could be pulled down, in case it fell on people on their way to work the next day.

Damage on the number 57 bus route at the corner of Poplar High Street and Cotton Street.

Further towards the City the underground stations made ideal shelters for thousands who slept on the platforms, arriving early to get the best spots. London Transport staff tried to keep the platform edges clear for the travellers. On 13 April 1943, I was on duty and went as usual to have breakfast in the Regent Café in Bow Road. The owner told me of a tragedy: 200 people had lost their lives at Bethnal Green station. I doubted this, as there had been no bombing incidents that night. Later, ARP headquarters told me there had been a rush to get in as the siren sounded. Someone tripped, people piled in behind, and hundreds were crushed to death.

As if on a film set, survivors gather together their few possessions in a street blasted apart by a V1 flying bomb.

Heavy raids on ports and factories came to a climax on 7 September, the ‘Battle of Britain’ as it became known. It started over London at about midday just as our workers were getting ready to go home. Everyone wanted to get transport out rather than stay in the shelters. As the train came in I was showered with brick dust and debris. As we left the station, there was a loud explosion. Through the windows we saw a huge blaze that marked the end of William Lusty Ltd, the factory that made Lloyd Loom furniture. It was one of the most memorable journeys I ever made. As the train arrived at each of the seven stations to Dagenham there were crowds gazing at the sky, where massed ranks of bombers flew in formation. When I got to my house, everyone was standing outside, cheering as the little Spitfires and Hurricanes weaved in and around this slow-moving target. Each victory was greeted with shouts and applause, as the bombers spiralled to earth, exploding in fields miles from their intended target, London’s docklands. Even so, the damage was widespread and as it grew dark, the sky over the East End was livid and the air-raid sirens were wailing once more as another group of raiders arrived to harry the emergency services, an easy target lit by the burning buildings.

Rescuers search the rubble of a bombed-out house where the collapsing roof has left a chance there might be survivors.

When I got to work the following Monday workmen were digging through a huge crater, all that remained of our underground shelter, which would have held most of our workers had they decided to stay.

A NEAR-MISS

Where we lived in Dagenham we had the May & Baker chemical factory near to one side of our home, and Ismay Cables and the Sterling Wireless building on the other. One night, the noise was unbelievable as a large number of bombs fell in succession, the explosions mingled with the pounding of the ack-ack. There was a prolonged whistle and a thunderous bang, followed by another three, coming nearer and nearer – then a break, and then a very large explosion seemingly only yards from our shelter. However, there was no follow-up blast or dust and debris that usually followed a building being hit, just a long vibration that shook the shelter and blew our candle over, then darkness. Torches were quickly found and switched on. We could hear the sound of the retreating plane followed by the rapid-fire barking of the guns, each with twelve barrels all firing at the same time. No one was calling out, as neighbours did after a near-miss, to check that everyone was all right, and rescue workers would arrive at the scene to see if they were needed, but this time all remained quiet. Then suddenly we heard from next door: ‘Blimey, John, that was close, I thought it was in your garden, it woke me up!’

A young female survivor is pulled from the cellar of her house.

The author is one of the group at the foot of the ladder, waiting to collect a box of spirits, a dog and a cat in a basket – followed by the landlady of this pub in Shoreditch, who insisted on going back for the till takings before allowing herself to be rescued from the second-floor window.

When daylight came we emerged to find that a stick of seven bombs had been dropped along the road, but one must have overshot and missed us out. He can’t have been a very good bomb aimer either, because the factories to the right and left of us were unscathed. After 7 September the bombers moved off to attack Southampton, Bristol and other cities, and the job of clearing up began. Army and navy squads undertook the very dangerous work of clearing up dozens of unexploded bombs and pulling down dangerous buildings. If there was one fate worse than being instantly vapourised, it was being buried under tons of collapsing rubble. Unexploded bombs continued to be dug up for years after, and there must still be many buried under the Thames between Hammersmith and Southend.

AND MORE NEAR-MISSES

Of course, the attacks did not end there. On 29 December there was an attempt to wipe out London with firebombs, followed by the dreaded parachute mines that few people had heard of. The following day, huge fires were still burning and I went out to take Taff, my brother-in-law, and his men some rations. The crew had just got back to base and Taff dragged me off to Leadenhall Street to show me something. The street was cordoned off and dangling from the telephone wires was a parachute mine, swaying back and forth in the gentle breeze, about ten feet long and the diameter of a galvanised dustbin. Taff’s squad had been working right underneath, oblivious to its presence. The bomb disposal squad was expected any minute. We moved well away from the area, directed by the man Taff had left in charge, as six naval personnel came with ladders and boards and defused the bomb.

Lilian and the girls had returned home after fifteen months as we had hoped the worst was over. The winter set in and we slept in the dining room, near the open fire. A raid began, and at about midnight we heard a deafening explosion, the shutters rattled but, as things then quietened down, we slept on. Lucy woke at the crack of dawn just as the all-clear sounded and went to the kitchen to make us all a cup of tea. Returning to the dining room she stopped in surprise and exclaimed, ‘Good gawd, look at all your faces!’. We looked at one another, then burst out laughing. We were all completely black with the soot that had been blown down the chimney. We had a job cleaning the house, and the ARP warden came by and reported that the bomb had landed in a potato field about 300 yards away. Later that morning I got a call at work. It was Lilian, to tell me that the whole estate was being evacuated. A huge parachute mine had been found in the field, about 30 yards from our front door. I got a lift home, to find that the Navy had arrived and disarmed it. We persuaded them to hang on while a hasty whip-round was organised to buy those brave lads all a drink.

A female ambulance worker hears the sirens going off.

There was massive devastation in Poplar and other parts of the East End from these mines. Unlike bombs, whose blast was dissipated mostly into the ground, these had tremendous sideways force and there was no hope of surviving within a range of about 400 yards. Our mine in Dagenham must have landed in earth too soft to trip the fuse, otherwise we should have booked an early daytrip to Heaven. Testimony to their frequent use on London was the number of stories of nightdresses, blouses, knickers and underslips run up from the parachute silk. The children even had silk skipping ropes, although they frayed easily.

WOMEN AT WAR

The women of Poplar were, in my estimation, the backbone of London’s defiance of Hitler’s onslaught. Many had seen their young children off on the evacuation trains and their sons and husbands off to the war. They had then taken up full or part-time jobs, often while looking after elderly parents, and were dealing capably with minor hindrances like ration books. Many of the elderly, of course, had memories of the Zeppelin raids and were reluctant to use the shelters.

Rearguard action: switchboard operators at work, their helmets and gasmasks at the ready.

We should never lose sight of the hardships the young mums suffered. Just staying and keeping their families healthy, with no National Health Service to fall back on. In some cases they had free medical care at work; otherwise, doctors wanted paying. A number took up evening duties. The Auxiliary Fire Service, or AFS girls, would do a shift at headquarters or go out driving supplies, often while the bombs were falling. In Women Fire Fighters, the ninety-five-year-old Cyril Demarne recognises their contribution; he was in charge of the Eastern region of London and I can vouch for many of the incidents he describes.

Then, there was the Women’s Land Army, the WLA. In his book War Time Women, Michael Bentinck recalls from interviews the stories these marvellous girls passed on. We heard about them on the cinema newsreels and saw them in their uniforms when they paid a flying visit back from the countryside to homes and relatives in the East End. They looked rosy cheeked and healthy, but we never knew what hard work they performed in helping to keep us fed. Many farmers treated them as cheap slave labour, and they have not always had the credit they deserve.

The huge volunteer army of the WVS gave untold assistance to the ARP, Heavy Rescue, Fire service and police. These ‘women in green’ have been well written about in a book by Chas Graves. They were organised to reach bomb sites while rescue work was underway to give comfort to tearful survivors and workers alike, with cups of hot tea made on the spot to fortify them against the dreadful scenes and experiences and to be on hand until there were no more survivors to be found.

A WVS volunteer came across a little old man searching in the rubble of his home, pulling out some of his recognisable belongings. She offered him a cup of tea and a bun. He sat down on a stool he had recovered and drank the tea, but refused the bun. A short while later he wandered up to the van and she said ‘Like a cup more tea?’ and he replied, ‘Can I have that bun now I’ve found my teeth?’

DOODLEBUGS

After four years of bombing there was delight and relief when we learned that the invasion had begun on the Normandy coast, with our Canadian and American allies. There was no possibility of repair work though, owing to the shortage of materials; besides, the residents were long gone. Poplar was a ghost town, piles of rubble everywhere with, here and there, a house that looked as though it had escaped destruction, until you looked more closely and saw that the rooms were all boarded up. With few customers and fewer goods to sell, it was a wonder any shops and factories remained open, but they did. Millwall was busy assembling and launching landing craft on the Thames slipway, and the famous Mulberry harbours that solved the problem of landing supplies behind the invasion forces, as no French deepwater ports had been captured. But it was a dreary place in the evenings when small groups of people made their way to huddle for the night in the shelters they found open.

At the time of the invasion, Hitler launched his secret ‘vengeance weapons’ on England. The first flying bomb to arrive was at Bow, in Grove Road. I saw it streak across the sky from Kent, and we all cheered, thinking it was an enemy plane shot down by the batteries furiously banging away on the other side of the river. Indeed, the BBC Home Service announced it in those terms the next day; that was all the Germans needed to hear. As they had lost no aircraft, they knew their V1 flying bomb, which soon came to be known by Londoners as the Doodlebug, had reached its target. There were many more to come.

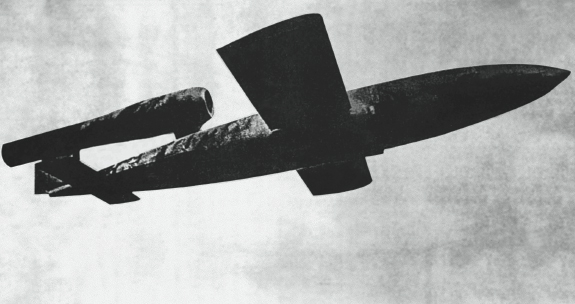

A V1 ‘doodlebug’ flying bomb, 1944/5. Hundreds of launch sites, known as ‘ski’ sites because of their curved shape, were hurriedly assembled in Holland and Northern France, pointing mainly to London, but the relatively inaccurate and slow V1 was soon to be superseded by something far nastier.

Twenty-five feet long, loaded with jet fuel and one ton of high explosive, with only a rudimentary guidance system the V1 bomb relied on a precise measure of fuel to reach its target: when the engine cut out, you had just 15 seconds before it came down. Carried on lorries and trains they were easy to launch, and there were hundreds of sites around northern France and Holland. The south London borough of Croydon was particularly badly hit, as many fell short of their central and east London targets. In the space of three weeks, fifty-six landed on Croydon, demolishing 60,000 homes. In total, over 4,000 got past the RAF, ack-ack and barrage balloon defences to the London area, and poor old Poplar got thirty-nine to add to the tally of devastation from the Blitz. This campaign carried on for about nine months until, one by one, the Allied invasion forces closed down the sites. Without the heroism of RAF and USAF aircrew on constant bombing missions to disrupt the V-weapons supply trains, it might have been a lot worse; the miracle is that Hitler did not order the use of his chemical and biological warheads.

The V1s were fast and hard to shoot down, but pilots developed an interesting method of dealing with them, aided by the Tempest aircraft which arrived to replace the ageing Hurricanes and which was faster even than the Spitfire. They flew alongside and used their wingtips to flip the ‘doodlebug’ off-course, hopefully to land harmlessly in the Romney Marshes. One New Zealand pilot was not so lucky, however; his plane collided with the V1 and he was killed, tragically as he was due to marry his WRAF officer sweetheart on the following Saturday.

A very large bomb crater in Cottage Street.

Devastation at Devitt House, Wade’s Place, Poplar, after an air raid in October 1940. Many elderly people were trapped in the upper floors of these tenement flats.

A warden calls for assistance as the dog seems to have found something.

Rigden Street, Poplar, after an air raid on 13 October 1940 in which four people were killed.

The King and Queen visited the East End, here on the site of The Eagle pub in East India Dock Road with the Mayor, Cllr Mrs Lilian Sadler and the head warden, Mr Cole. Princess Margaret is on the right and Princess Elizabeth has her back to the camera.

Fortunately, Hitler then directed most of the V1 onslaught on to Antwerp, where the Allies now had the deepwater port they needed to unload supplies for the invasion forces facing counter-attack in the Ardennes.

After the V1 came the V2, a much more sinister and powerful guided rocket that weighed 13 tons and travelled at 3,000 mph. We owed a great debt to Miss Babbington-Smith, a WRAF reconnaissance officer, who first spotted the assembly and launch sites at Peenemünde on the Baltic, enabling the Allies to launch bombing raids against them. The first one to land was at Chiswick, and the BBC gave out details of a ‘gas explosion’ that did not fool anybody, least of all the Germans. We christened the V2 the ‘Flying Gas Main’, but it caused panic in the Government and despair among many Londoners. Was there no end to it?

Some colleagues and I narrowly missed becoming victims of one of these missiles. We had planned to meet up for lunch at the Cotton Street pub in East India Dock Road, a short bus ride from the office, but were late getting away and had to wait for another bus. Just before we reached the Blackwall Tunnel, we heard a huge explosion. Everyone was running, crying and shouting, many covered in glass, dust and blood. We felt a bit incongruous in our clean suits, staring at the pub and its surrounds, completely demolished, and bits and pieces of what looked like old clothes, but were in fact body parts, scattered around. There was nothing we could do there except get in the way, so we returned to the bus stop, pausing on the way to buy some ‘lunch’ from Mark’s, a wonderful bakers I had known as a child. They fed us with buns and scones, and would not take a penny.

The author’s brother-in-law, Gordon ‘Taff’ Eardley, a City of London Heavy Rescue worker, leads a VE Day celebration goat-cart ride. He is seen in action earlier on page 99. The author’s daughter Shirley, aged ten, with bow in her hair, watches her brave uncle from the background.