Chapter 3

When You Wish Upon a Star

When the studio became overwhelming for Bianca, as it had a tendency to do, her favorite place of refuge was the Los Angeles Public Library. It stuck out like a sore thumb among the department stores, hotels, and banks that lined Fifth Street in downtown Los Angeles. The urban landscape reflected the city’s rapid growth over the past three decades. Thanks to the region’s sunny, moderate climate, ideal for year-round shooting, moviemakers had begun flocking to Southern California in the early 1900s. At the same time, a metal forest of oil derricks started spreading across the Los Angeles Basin.

The first boom occurred in 1893 when prospectors struck oil in the area that is now home to Dodgers Stadium. By 1923, the region was producing one-quarter of the world’s crude oil. The influx of new industry meant that the city was growing at a frenzied pace. Its population doubled between 1920 and 1930, rising to more than a million and making Los Angeles the fifth-largest metropolis in the United States. The swift growth was reflected in the skyline, its architecture a hastily erected mix of art deco office buildings and the low-pitched red tile roofs of Spanish colonial revival homes.

Bianca skirted the edges of multiple construction sites downtown early one morning. Around her, a mass of pedestrians was getting off the city’s streetcars, a system made up of Los Angeles Railway’s Yellow Cars and Pacific Electric Railway’s Red Cars. It was the largest transit operation in the country, busier even than that of New York City, and choked the avenues by midmorning. Bianca was headed to the library, a rare patch of green within the growing city. A path of trimmed arborvitae and three long reflecting pools led her to the white stone steps of its grand entrance.

There was no mistaking the library for any other building in town. Its construction in 1926 marked a period of Egyptian frenzy in the United States. Just four years earlier, an excavation team had uncovered King Tut’s tomb in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, on the west bank of the Nile. The discovery of the mummy of young pharaoh Tutankhamen, along with his earthly treasures, was the archaeological triumph of the twentieth century.

The Western world was soon swept up in “Tut-mania,” a craze influencing art, fashion, film, jewelry, and even architecture. The Los Angeles Central Library was modeled after ancient Egyptian temples, and atop its tower rose a vibrant golden pyramid adorned with tile mosaics that could best be seen from the sky. Above the west-facing entrance, Latin words were inscribed on the stone façade: Et quasi cursores vitai lampada tradunt, meaning, “Like runners, they hand on the torch of life.” At the pyramid’s peak, covered in a shiny gold alloy, was the embodiment of these words: a hand grasping a fiery torch stretched to the heavens.

Bianca passed under these words on her way into the library, which had become in many ways her temple. It was everything the studio wasn’t: quiet, respectful, and filled with women. She brushed her hand against the black marble sphinxes at the top of the staircase before heading into the stacks. Although it might seem she was merely avoiding work, she had a reason to be here. Walt had just announced that Pinocchio, not Bambi, would be their next feature film.

Although Walt had finally gotten his hands on the rights to Bambi a few months earlier, he had been disappointed in the animators’ early sketches for it. He described the deer as “flour bags,” animals without shape or dimension. Walt wanted to move away from a cartoonish look and mirror the environmentalist message of the story with a more realistic style. It was clear that the project needed more time in development.

Bianca immersed herself in the project of adapting Pinocchio. She sat between rows of books or sometimes found a quiet desk in the children’s literature section and wrote story treatments. The studio on Hyperion Avenue boasted its own library, of course, the shelves primarily filled with the work of illustrators; many of its volumes Walt had personally selected and brought back to the United States from family holidays in Europe. Given that the team was focused on European fairy tales, perhaps it was no surprise that the artists drew inspiration from the work of Richard Doyle, Gaspard Dughet, Paul Ranson, and J. J. Grandville, among others. The staff would perch the ornately bound books precariously on corners of their old, scarred desks and emulate in their sketches the drawings they found inside. Yet among the hundreds of prized books, there were relatively few works of fiction, and so when Bianca wanted new source material for her story ideas, she was only too happy to leave the studio and head to her favorite building downtown.

Browsing through the library’s novels, she had found nothing to rival the book she already had, Walt’s personal copy of Le Avventure di Pinocchio: La Storia di un Burattino, by Carlo Collodi. First printed as a serial in an Italian newspaper and then published in its entirety in 1883, the book found immense popularity among readers in English-speaking countries as The Adventures of Pinocchio.

After multiple readings, Bianca knew the story—the tale of the pitiable wood-carver and his mischievous marionette—intimately. Walt had been tentatively considering it for over a year, but although he owned several English translations of the book, he turned to Bianca for a fresh take on it. He appreciated that she was the only member of the story department capable of reading it in its original Italian and then assessing its potential as a feature film. The library was a quiet place to read and work, and Bianca was soon lost in the text, her pencil flying across her notebook as she translated bits of dialogue from her native tongue.

As she delved deeper into the novel, however, she began to have reservations about its adaptability. The character of Pinocchio is, in many ways, unsympathetic. He is inherently cruel and frequently selfish, kicking the wood-carver Geppetto the very moment his creator carves his feet. In the original serialized version, Cat and Fox hang Pinocchio for his crimes and disobedience, thus ending the children’s story with his vivid death: “His breath failed him and he could say no more. He shut his eyes, opened his mouth, stretched his legs, gave a long shudder, and hung stiff and insensible.”

After this first serial ran, Carlo Lorenzini, who wrote under the pen name Carlo Collodi, was ready to move on from the puppet’s story, but his editor Guido Biagi did not want him to. The series was immensely popular, and Biagi pleaded for its continuation. He suggested resurrecting the insolent puppet and giving him a path to redemption that would occur over twenty more installments, culminating in a fairy with turquoise hair transforming the remorseful wooden child into a real boy. Six months later, after requests from not only his editor but also readers, Lorenzini agreed to continue the serial, eventually ending his story with the line: “How glad I am that I have become a well-behaved little boy!”

Bianca loved the tale. There was something powerful and unexpected about this wooden puppet’s desire for life. But although she could clearly see the possibilities, there was something missing from the plot. In those final twenty chapters, Pinocchio dreams of becoming a real boy at last, but his motivation isn’t explained. As the sixteen original chapters of the story make clear, Pinocchio can do nearly everything a real boy can. He can eat, run, sing, and cause mischief like any child. In fact, Bianca realized as she made her notes for Walt, unless they animated the wood joints and strings clearly, there would be no way for an audience to distinguish Pinocchio from any other child on-screen.

So if the puppet can do all these things, Bianca wondered, why does he want to be a boy? They needed to give the puppet a reason to want life, a spark that would make the troublesome character sympathetic and give the story greater meaning. Bianca made a list of possibilities. It could be for love, the longing to grow up and kiss the girl of his dreams, or it could be so that he could one day become a man and not be condemned to remain a small child all the days of his existence. In her quiet sanctuary, Bianca contemplated all the reasons one might choose to be alive.

Strange devices were taking over the film industry in the 1930s. New camera and projection motors were able to sync their shutter speeds, making possible a rear projection system that allowed inventive backgrounds to be placed behind actors. A couple could sit in a car going nowhere as the background raced behind or beside them, giving the illusion of movement. For the first time, movie studios had special effects departments that created miniature ships to fight pirate battles on the seas of a soundstage, yanked doors open with wires as if by magic, and built trick floors that made disembodied footprints appear in the snow.

Although Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer had been the last major studio to convert to sound, by the late 1930s it was leading in special effects. In 1938 Arnold Gillespie, MGM’s special effects coordinator, was working on an upcoming film called The Wizard of Oz. He threw away the studio’s lifeless rubber tornado, which looked more like a gaudy orange traffic cone than a devastating storm, and began observing the undulating wind socks that were used to determine wind speed and direction at the airport. He had never seen a tornado in his life, had never even set foot in the state of Kansas, yet he recognized something familiar in the way the sock filled with wind. It moved as if it were alive. Inspired, he took a thirty-five-foot-long muslin sock, surrounded it with fans placed at just the right angles, and proceeded to blow dust across the MGM soundstage. The tornado that he created would shock audiences when they finally saw it on-screen in 1939. Moviegoers turned to each other as they exited theaters across the country and asked in excited voices, How did they do that?

Walt was asking a similar question. While every live-action movie studio was clamoring for realistic special effects, he wondered how to bring realism into the world of animation. Not to be outdone by the live-action studios, he appointed an effects supervisor for Pinocchio, Robert Martsch. Walt’s goal was to bring new techniques to the film, to create a groundswell of artistic achievement that would separate cartoon from animation and make their scenes as lifelike as a terrifying tornado fabricated from a long, dusty sock.

The zeal for visual effects was reaching into every department of the studio. In the all-female Ink and Paint department, the women were developing “the blend.” A woman in the department named Mary Louise Weiser had originated the technique using a pencil of her own invention that she nicknamed a “grease pencil.” Standard pencils could only feebly scratch the glossy, nonporous surface of the cels. Weiser’s pencil had a waxy exterior that the women could rub across the borders of their colors to soften their lines and create shading and depth; for example, it could tint the cheeks of a character with a diffuse, natural blush. Weiser filed a patent for the grease pencil in 1939, and eventually, its utility would reach far beyond the studio. It became an essential component of military defense and aircraft control centers in the 1950s, used to mark the locations of aircraft, weapons, and fuel on panels of glass.

In their separate workspace at the studio, the women of Ink and Paint experimented with other techniques, dabbing their cels with sponges and then rubbing the grease pencils sparingly across the surface, giving the characters’ faces a youthful roundness; Pinocchio’s body got a drop or two of lacquer to give it the look of real, polished pine. The women also wiped stiff, dry brushes across the cels’ plastic to give texture to Figaro the cat’s fur while adding vivid new colors never before seen on-screen to their palette.

While the group received little formal acknowledgment for their contributions, there was undeniable camaraderie in Ink and Paint. It was enough to make the other women of the studio occasionally wistful at their more isolated experiences, particularly Bianca, who was reminded of her own thwarted efforts in the story department.

Bianca yearned to bring emotional depth to the script for Pinocchio and she fretted over the puppet’s character, which, despite her best efforts, remained mischievous and, she worried, unlikable. The story team seemed more concerned with creating gags for him, crafting a brash personality that echoed the original Collodi story but did not fit Bianca’s vision for the film. Other characters who could balance the harsh quality of Pinocchio’s nature, such as Jiminy Cricket, had not yet been substantially developed.

Other constraints weighed on Bianca. Proud of the success of her Elmer Elephant short, she began writing additional scripts for the character. She was encouraged by both the short’s popularity and the opinion of Walt’s distributor, who hinted that merchandising the elephant would likely prove profitable.

Walt, unlike the heads of other animation studios, jumped into selling character-branded merchandise early on, beginning in 1929 when a man offered him three hundred dollars to put Mickey Mouse’s face on notebooks marketed to children. Walt agreed, not because he believed the venture would be particularly successful but simply because he needed the money. To his surprise, merchandising quickly turned lucrative. By the mid-1930s, the Ingersoll-Waterbury Company had sold more than two and a half million Mickey Mouse watches, and other small toys and dolls were moving quickly and bringing the studio needed income. The potential was there, yet Elmer was going nowhere.

Despite her abilities, Bianca couldn’t get another script approved. She wrote one script she was particularly proud of, Timid Elmer, in which she enlivened the warmth of her main character with playful gags, like Elmer using his trunk to trip a monkey, that she knew would appeal to most of the members of the story department. But even this didn’t work—Walt was completely uninterested. In early 1938 it seemed to Bianca that everything she touched was fated for oblivion, discarded before she could prove its worth.

By early June, however, Walt was in agreement with Bianca on the Pinocchio script’s troubles. He, too, saw Pinocchio as unsympathetic and viewed his stunted character development as poisoning the rest of the narrative. The gag-driven script was at its core immature and, to Walt, past all redemption. To the shock of those at the studio, Walt threw everything away. It didn’t matter that the team had already worked for five months on the project, produced 2,300 feet of film, and spent thousands of dollars. They would all have to start from scratch.

The story department was in crisis. Following Snow White, some writers had bragged about how well they understood the complex nature of feature-length animation, but now that puffed-up confidence evaporated. Amid the general gloom and the nagging feeling that they were chasing an unattainable standard of perfection, Bianca found herself returning to notes she had made a year earlier. She was one of the few in the story department who had a smile on her face.

Walt wasn’t letting the reset affect his optimism for the future of their endeavors. Just two months after he scrapped all work on Pinocchio, he was ready to fund his next big venture. Money was no longer a primary source of anxiety. In the first six months after the release of Snow White, the studio not only paid off its debts but also grossed four million dollars. Walt, along with his brother Roy, made a ten-thousand-dollar down payment on fifty-one acres for their new dream studio in Burbank. Walt Disney Studios, which now had approximately six hundred employees on its payroll, was outgrowing its modest dwellings on Hyperion Avenue.

The current lot held two animator buildings, a soundstage, the Ink and Paint annex, and a new features building constructed just that year. Yet space was in short supply. The animators sat crammed at their desks, their elbows rubbing against one another’s and occasionally causing Mickey Mouse to sprout whiskers on the top of his head, and in the story department the noise level had reached new heights. And with production ramping up on a new feature, even more workers were moving into the buildings on Hyperion Avenue.

August 1938 brought with it not just the promise of new buildings and spacious offices but a fourth woman in the story department. Her name was Sylvia Moberly-Holland, and working for Walt had been her ambition since she’d sat in a darkened theater and felt the enchantment of Snow White sweep over her. The film was life-altering. As soon as the lights came on, Sylvia turned to her mother and in an excited voice declared, “I’ve got to do that.” She quickly found a job as an inker with the Ink and Paint department at Walter Lantz Productions at Universal Studios. She saw the job as a stepping-stone, a way to attain her all-consuming desire: to work for Walt Disney.

By the summer of 1938 there was a rumor circulating around Hollywood that Walt’s next movie after Pinocchio would be a musical feature. This greatly piqued Sylvia’s interest, as music had formed an essential part of her childhood, a joy she had shared with her father, a vicar in the small English village of Ampfield, where she was raised. Excited by the possibility of combining music with her art, Sylvia applied to the studios and was granted an interview with Walt himself.

This was highly unusual. Most women hired at the studio were in their early twenties, unmarried, and unattached. They were placed in a training program and only a fraction of these women would go on to join Ink and Paint. Advertisements run by the studio in the 1930s proclaimed: “Walt Disney Needs Girl Artists Now! Steady, interesting jobs for girls, 18–30 with elementary art training. No cartoon experience needed; we’ll train you, pay you while you learn. Apply Disney Studios, Art Dept. Bring samples of your work.” Sylvia didn’t fit the criteria—she was a thirty-eight-year-old widow with two small children—but she needed this job desperately.

When she was a child, Sylvia received as a gift an early Kodak point-and-shoot box camera that she excitedly aimed at garden roses, craggy rocks, and the wild heather that grew across her native English countryside. She developed the photographs in her grade-school bathroom, much to the chagrin of her teachers, who took issue with the sinks of the girls’ room being constantly filled with soaking prints.

As a teenager, Sylvia was sent to the Gloucestershire School of Domestic Science, a respectable school for young girls to learn the work of women: cooking and teaching. She lasted two years in the program before moving on to the Architectural Association School in London, transferring from a school of all women to one that contained practically none. When she graduated, she was the first woman to join the Royal Institute of British Architects.

In the first bloom of her career, Sylvia was fortunate. One of her early projects was designing the British Pavilion at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts held in Paris in 1925. She had her degree, meaningful work, and the love of a man named Frank Holland, a fellow student. The two married and then moved more than four thousand miles away to begin their own architecture practice in Victoria, British Columbia. Sylvia quickly made an impression in her new country, becoming the first woman accepted to the Architectural Institute of British Columbia.

In 1926, the couple welcomed a little girl, Theodora, whom they called Theo. In her home office, Sylvia leaned over her drafting table, sketching the lines of light-filled rooms while she gently rocked her infant daughter in a cradle placed at her feet. Vibrancy and joy filled their Canadian home. Frank and Sylvia were young and very much in love, and their shared passion for the elegant Arts and Crafts–style homes they designed together was eclipsed only by their excitement at their growing family.

Pregnancy and birth will often make a woman reflect on her own upbringing, and so it was for Sylvia, who, seven months pregnant with her second child, longed to see her parents in England, particularly her mother, who had never met her granddaughter. The journey was expensive, so she took one-year-old Theo with her to England, leaving Frank alone at home.

She left behind a bitterly cold December in British Columbia, with temperatures dropping to 10 degrees, far below what was typical of their normally mild winters. The streets were buried in snow, but that didn’t keep Frank from Christmas shopping, his spirits high as he thought of Sylvia’s imminent return. Then he fell ill. Frank lay in bed, burning up with fever. His condition quickly deteriorated as pain and pressure in his ear became excruciating. A physician’s exam confirmed what was obvious to Frank: he had an ear infection. However, the doctor could offer no treatment. The bacteria spread, reaching Frank’s inner ear and then infecting the mastoid process, the part of the skull behind the ear. Unlike most of the rigid bones in the human body, the mastoid process is porous, like a sponge, and filled with air cells. Bacteria can invade these spaces, leading to an infection that eventually reaches the brain. In the 1920s there was no medicine or surgery that could stop the progress of the deadly infection.

Just three months earlier, in September 1928, a Scottish bacteriologist named Alexander Fleming returned from vacation to find, in his messy London laboratory, a mold called Penicillium notatum growing on his petri dishes. The mold had the mysterious ability to kill several strains of bacteria responsible for human infections. Although Fleming was intrigued by the lucky accident, it would be sixteen years before researchers found a way to mass-produce the antibiotic known as penicillin. These advances came far too late to help Frank. Within weeks, the bacteria reached his brain and he died.

Sylvia returned to Canada a widow. She was twenty-eight years old and pregnant; shortly after she arrived home, she gave birth to a baby boy, whom she named Boris. In the throes of grief but with a toddler and a newborn depending on her, Sylvia tried to find a new rhythm for her life. She had always seen herself as resilient and independent, and she tapped into that inner strength as she tended to her children and planned for the future of the architecture firm that she now ran alone. The timing, however, was not in her favor. The next year, 1929, brought a worldwide economic crash. In the midst of the Great Depression, most people were losing their houses, not building new ones. Sylvia’s steady work as an architect vanished.

One in a series of sketches drawn by Sylvia Holland depicting the death of a loved one and the grief of those left behind (Courtesy Theo Halladay)

Years passed, but little improved for Sylvia. She received few commissions and struggled to pay the bills. In desperation, she moved to the Holland family farm outside the city, where she paid rent to her father-in-law. Then, when it seemed their situation could not get worse, Boris fell ill. The child clutched his ears and cried in pain, and when she looked into his eyes, Sylvia feared he’d suffer his father’s fate. She pleaded with the doctor to do something, but the physician had nothing to offer. Ear infections were a leading cause of childhood mortality in 1930 and widely available antibiotics still more than a decade away. Yet the doctor felt deep sympathy for the panicked mother and gave her the best advice he had: “Get him to a desert climate,” he told her, then added ominously, “or lose him.” The next day Sylvia and her children were on a southbound train headed for the medicinal sunshine of Los Angeles.

The move meant Sylvia had to leave her architecture firm, but it also necessitated a more painful separation. In Southern California, after Boris recovered, Sylvia placed her two children in a boarding school, vowing that she would find work quickly and reunite her family. And so, with a determination that few other applicants could match, Sylvia walked into Walt’s office on a clear summer day in 1938 and pulled out her sketches. Invisible to others was the nearly unbearable weight of the past few years she carried on her shoulders—the anguish of grief, the financial and emotional toll of losing her husband, the recent illness of her son, and the despair of leaving her children. Few people would still be standing after suffering the blows she had endured. It seemed that everything she held dear was riding on the success of this one meeting. Fortunately, Walt immediately perceived Sylvia’s talent, and he hired her on the spot to begin work in the story department.

Although, like her female colleagues, Sylvia was paid less than her male counterparts, she still earned more than she had in her last job, where she’d gotten about twelve dollars a week. The Walt Disney Studios were known for offering higher salaries than most of their Hollywood competitors. Yet even this extra income was not enough to bring her children home. She longed for the sweetness of everyday family life, and that desire drove her to exert herself to the utmost.

Sylvia was sitting at her desk one afternoon working on story ideas when she heard Walt walking down the hallway yelling, “Anybody know how to draw a horse?” Sylvia didn’t waste a moment; she jumped up and yelled, “I do!” In truth, there was nothing he could ask for that she would not immediately attempt. She walked alongside the boss, sketching quickly on a piece of paper as they made their way down the hall. In mere moments she finished the drawing and handed the horse to Walt. As a result of that one hurried sketch, Sylvia received an opportunity at the studio that no other woman had yet garnered. And it would begin at a story meeting.

Sketch of a horse made by Sylvia on scrap paper, date unknown (Courtesy Theo Halladay)

Attending story meetings at the Walt Disney Studios was akin to getting one’s boots stuck in soft spring mud—once you were in, it was nearly impossible to get out. Grace Huntington spent 1938 in an endless number of such meetings. They took place Monday through Saturday, often first thing in the morning, with the group poring over every detail of the script and storyboards. Grace was working on a new Mickey Mouse short and she could hardly believe the countless hours spent on what, ultimately, would be a mere eight minutes of family entertainment.

Despite a solid week of work on the Mickey short, the team of story artists had barely made a start. Until they had a finished script and storyboards approved by Walt, the animators couldn’t begin their work, and the whole project hung in limbo. At nine thirty a.m. Grace and her colleagues shuffled into the room, ready to start debate over Mickey Mouse again. These walls had become as familiar to her as the seven men she shared the space with.

The group quieted down, and Peter Page, whose name was perfectly suited for his position as a writer in the department, began running through the storyboards, summarizing the action and calling out all the dialogue. His voice squeaked like Mickey Mouse’s as he described how the character meets Claudius, king of the bumblebees, and is then magically shrunk to the size of a bee. The room was silent for a moment, the calm before the storm, before the other team members began to rip the story apart, attacking every facet of the plot.

Grace was quick to offer her criticism, saying, “The whole story is built on something that isn’t true in the first place, because they have a king of the bees and bees are known to have a queen. Not that it makes a lot of difference, but right there it isn’t true to life. The head of the hive is the queen and the males do very little except fly around and enjoy themselves.” Grace looked around the room with a wry smile before continuing, “It seems to me if we had the queen of the bees it would add to the story because at the end it is the queen who is in trouble; she is captured by the wasps. If Mickey were to save the queen it seems a stronger story point. Then he can save the whole hive by beating their armies.”

“There again you have a false assumption because a queen never leaves a hive,” Peter responded.

Grace shook her head. “She doesn’t have to leave.”

They continued to argue over the short for the next few hours. Grace suggested a new approach to animating the bees in a way that would augment their story line. She tacked up her sketches of bees with light humanistic touches, their black legs dangling from their bodies. The men of the meeting widened their eyes before asking, “No clothes?”

“No clothes” was Grace’s firm reply.

Grace left the story meeting feeling they had accomplished but little. She was pleased that her work on the short, particularly sketching and writing the climactic battle scenes, would continue but unhappy about nearly everything else. Like Bianca, she was growing increasingly frustrated at how often her ideas were disregarded. Her personality was not mild—she spoke boldly at meetings, and she could be as passionate as any story man when tacking her sketches to the storyboard. Still, it seemed she had to push unusually hard for her ideas to gain traction.

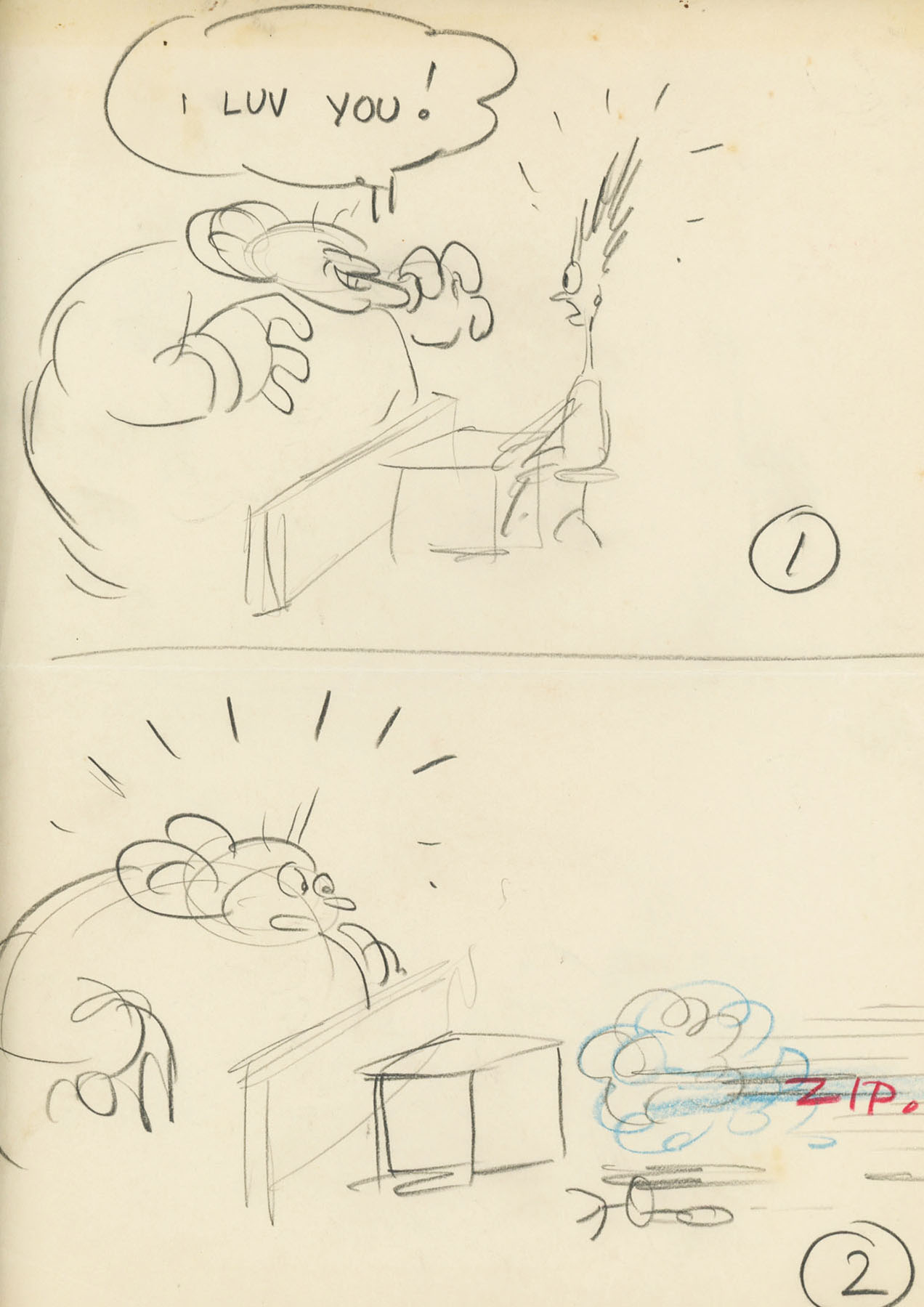

The problem wasn’t that Grace couldn’t attract attention. A current of flirtation ran through the office, and Grace found that her male colleagues weren’t interested in her story ideas, but they were interested in dating her. Focusing on her youth and beauty, they frequently brushed aside her writing. She complained to Bianca and then vented her feelings onto her sketch pad, repeatedly drawing an obese and overbearing Mickey Mouse. Sometimes he leered at her over her desk in her sketches, proclaiming, to the cartoon Grace’s obvious horror, I luv you!, with menacing hands and an impish smile. Grace’s desire to flee was represented in the next frame, where all that was left of her was a cloud of dust and the word Zip!

When she wasn’t using her free time to lampoon the image of Mickey Mouse, Grace liked to sketch airplanes, which remained her passion. The shapes of her imaginary aircraft were buoyant above the clouds, and she invariably placed herself in the cockpit, a content smile on her lips, her own initials gracing the tailfin. She still dreamed of becoming a licensed pilot. On paper, at least, she was free to leave the limits of the earthly studio and take to the air.

While Bianca and Grace felt that their careers were progressing slowly, the studio as a whole continued to break new ground. In his quest to advance special effects in animation, Walt founded a new airbrush department, the aim of which was to produce realistic visual effects, particularly in the backgrounds of scenes. An airbrush uses a jet of compressed air that acts as a pump, drawing the paint from its reservoir in a cloud of tiny droplets to create a mist of color. The technique was developed in the late 1800s and first used by American Impressionist painters, who found the gentle spray ideal for portraying the diffuse glow of natural light. Soon after that it was adopted by illustrators and muralists as well as photograph manipulators, who used the delicate application of paint to retouch or doctor images.

Grace Huntington’s depiction of life as a female artist at the studio (Courtesy Berkeley Brandt)

To lead the new department, Walt hired Barbara Wirth Baldwin. Barbara shaped the group, growing it to twenty-five men and women. There was grumbling among the male artists about having a woman as their leader. Bristling at any display of femininity, they were especially vexed when Barbara insisted that her group wear hairnets to prevent a single strand of hair or flake of dandruff from falling onto the cels. Barbara laughed off their complaints with a firmness that spoke of her innate confidence and quickly got down to the responsibilities of her job. She started by working with the massive multiplane camera housed in its own chilly studio space. Holding the nozzle of the airbrush steady, she pressed the trigger ever so gently and painted clouds directly on the glass. She was incredibly nervous while airbrushing in the studio for the first time, aware that the slightest touch of her fingers could ruin the art irrevocably.

Barbara and her team worked closely with the special effects animators in creating a range of visuals for Pinocchio that had never been attempted before and in pushing the capabilities of the multiplane camera. The airbrush allowed the film to include subtle touches, such as the haze of smoke and the luminosity of moonbeams. Barbara’s team distorted the edges of goldfish Cleo’s bowl with airbrushed shadows and specially fitted glasses placed on top of the camera lens. They took real twinkle lights and fastened them into a black canvas, then used the airbrush to spread gray paint over the surface so that it glowed like stardust between blazing suns. They even showed the saltwater spray of fierce ocean waves and the flickering of candlelight in the darkness, and they imbued the Blue Fairy with her heavenly glow.

The delicate artistry of their special effects contrasted with the darkness of the tale they were telling. In Collodi’s original text, Pinocchio bites off a cat’s paw and later kills Jiminy Cricket. Although the story department ultimately stripped away much of the horror, a dark mood clings to the film’s dialogue and characters. The ominousness is reflected in its cinematography: seventy-six of the film’s eighty-eight minutes are either in darkness or underwater.

The bleak concept art they were producing for Pinocchio reflected the fearful headlines studio employees were reading in their newspapers each morning. Bianca watched in horror in 1938 as Benito Mussolini, the dictator who ruled her native Italy, legalized a set of racial laws that stripped all Jewish Italians and other targeted minorities of their citizenship. It was clearly a grim portent.

Many employees with European ties were nervously following the news, including Sylvia, who was on the hunt for updates from England. After Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain signed the Munich Agreement in 1938, he announced that “a British Prime Minister has returned from Germany bringing peace with honour. I believe it is peace for our time.… Go home and get a nice quiet sleep.” Instead of resting, fifteen thousand people protested in Trafalgar Square. For those who opposed Chamberlain, it was clear that instead of the peace he promised, turbulence was ahead. Perhaps it’s unsurprising that, hearing of such disturbing developments, the studio artists chose to include in Pinocchio so many of the dark elements of Collodi’s text.

Contrasted with the gloom, however, is the well-meaning sweetness of the wooden puppet. Thanks to dramatic revisions by the story department and an expanded role for Jiminy Cricket, the film was transformed into something closer to Bianca’s original concept, a tale that attempts to show what it means to be human.

The character Bianca crafted and that she advocated passionately for in story meetings was starkly different from the original wooden puppet. Her character does not arrive in the world with a malicious heart, but, like many of us hapless humans, he is frequently led into sin. He is exposed to what is arguably the worst society has to offer: thieves who take advantage of him, a man who imprisons him and threatens him with murder, even child trafficking. By making Pinocchio more like us, a flawed being trying to navigate the world as best he can, Bianca ultimately magnified Collodi’s themes about the meaning of life. It doesn’t matter whether one’s limbs are wooden or flesh; it is not our bodies that make us human but the way we treat one another.

Bianca would receive little public acknowledgment for her contributions to the film. Neither would many others. The movie’s credits, like those of Snow White before it, were a source of anger and resentment. Only a fraction of the artists and writers who worked on Pinocchio saw their names on the silver screen. Despite the stunning technological advances made by Barbara Wirth Baldwin and Mary Weiser, neither woman’s name, nor that of any other female employee, was included. The absence of acknowledgment for women’s efforts on the film was echoed in the paltry number of female characters, only one of whom—the Blue Fairy—spoke at all.

When Bianca arrived at work on February 7, 1940, she found the men crowded around a copy of Hollywood Citizen News, a local newspaper. Bianca wasn’t surprised. Today marked Pinocchio’s release and everyone was anxious for reviews.

Bianca was settling in at her desk when one of the men called her over. “Bianca, this one’s about you,” he yelled. Confused, Bianca ambled over to the group and took the newspaper with no suspicion of what its pages contained.

It is no longer news when a woman takes her place in a man’s workaday world. But it was news when a woman artist invaded the strictly masculine stronghold of the Walt Disney Studios. The event took place about five years ago. Until that time the only girls in the studio were the few necessary secretaries and the girls who did the inking and painting of celluloids. The girl who caused all this excitement was a young artist who, as a child, had gone to school with Walt in Chicago.

Bianca laughed at the piece, and before she gave the paper back to her colleagues, she sardonically wrote in the margin, Who is this girl? The reporter had found it unimportant to mention her name.