Chapter 12

You Can Fly!

Occasionally the plane caught a tailwind that pushed it across the country faster; traffic on the highway toward her house mysteriously evaporated, and even her heels clicked more quickly across the pavement. For a woman who traveled as frequently as Mary did, regularly commuting between New York and Los Angeles, the joy of getting back early was keenly felt. It was wonderful to turn your key in the door, drop your bags, and embrace the comforts of home. But that was not what happened today.

Mary opened the front door and heard voices coming from the adjoining room. Walking in, she saw her husband sitting with a pad of paper and pencil. In front of him was a woman posing with not a stitch of clothing on. A terrible silence hung around them. It was clear to all what Mary had just stumbled upon. The atmosphere was nothing like the innocent life-drawing classes the couple had enjoyed at the studio. All her suspicions of Lee’s unfaithfulness were instantly confirmed. Mary turned to the young woman who had been sleeping with her husband and said, “You must model for me sometime.” Then, without a word to Lee, she spun on her heel and left the house—albeit temporarily.

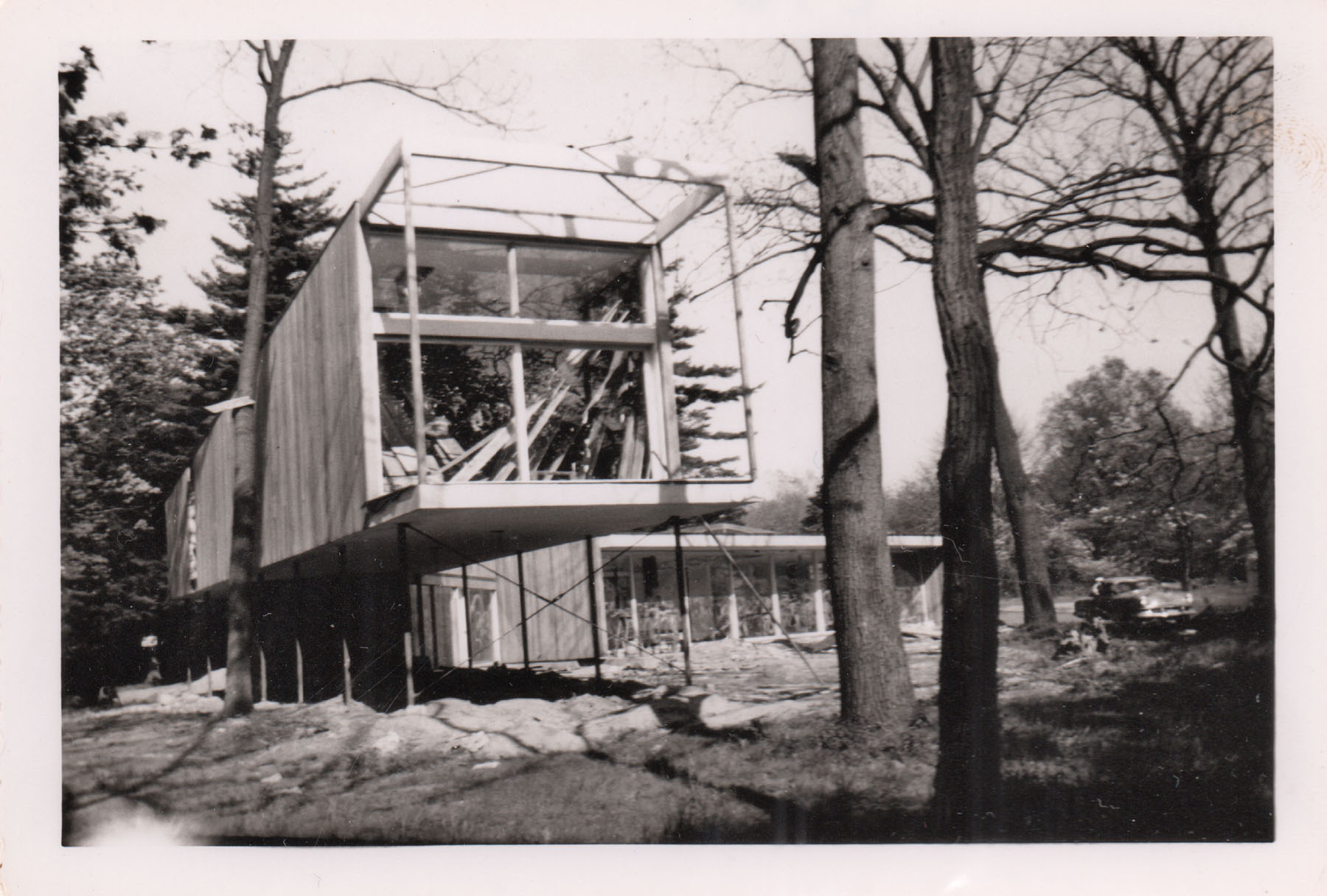

She was walking out of her dream home. The sprawling four-bedroom mansion the couple had built in Great Neck was close to the sparkling waters of the Long Island Sound, where the family frequently went sailing on their boat. Such an excess of luxury was something Mary could never have dreamed of as a child in Oklahoma.

An art studio with its ceiling and three of its walls made entirely of glass sat perched in an elevated wing of the home. A real estate agent might call it a “jewel box,” but it felt to Mary like a glass cage. It was undeniably a beautiful place to live and work, but it did not offer her shelter from the increasing abuse of her husband.

Mary’s glass studio at her home in Long Island, New York (Courtesy the estate of Mary Blair)

As Lee was not inclined to share in the labors of married life, Mary was raising their boys essentially on her own and keeping house herself while putting in long hours on her artwork. They had some hired help, particularly necessary during Mary’s travels, but not nearly enough. Mary was overwhelmed. It seemed that the burdens of their family were hers to bear alone. Lee was often out, working or, possibly, sleeping with other women—until the incident with the model, Mary hadn’t been sure. When he was home, he sometimes drank so much that his conversation devolved into cruel barbs at Mary before he finally, mercifully, passed out.

Mary did not know what to do. She was becoming like the Alice of her brightly colored paintings. In California she spoke cheerfully to her colleagues about her home life, devoted husband, and sweet boys. In her letters to and conversations with Walt, she was always circumspect, never giving a hint of the difficulty she faced at home. But on the plane back to New York, she felt she was falling down the rabbit hole, returning to a life that was as bewildering as Wonderland and much more miserable.

Divorce was an ugly word in 1951. Many women felt immense shame in leaving their husbands and were often told that a broken covenant was their own personal failure. The stigma that persisted could tarnish even a reputation as brilliant as Mary’s. Approximately 25 percent of all marriages of the era ended in divorce, a rate that would stay constant throughout the 1950s, due in part to laws governing how couples could legally separate. It was not yet possible to cite irreconcilable differences—one member of the couple had to show evidence of adultery or cruelty. Faced with these options, Mary chose to stay, despite this latest incident. She had always loved drinking martinis with friends, but now when she reached for her glass, she was drinking not in the spirit of the occasion but to drown out the pain that was screaming within her.

Two hundred miles to the northeast, a group of engineers in Cambridge, Massachusetts, were working on a machine with roughly the same square footage as Mary’s grand house on Long Island. Jay Forrester was determined to build the fastest computer in the world using more vacuum tubes—thin-walled cylinders that conduct electrical charges—than any other computer anywhere. The project had started in 1943, when, under the pressures of war, the government tasked the servomechanisms lab cofounded by Forrester at MIT with designing and building a flight simulator to train pilots.

The war ended before they finished their research on Project Whirlwind, yet the engineers could not leave the challenge behind. So the group shifted focus; they were no longer interested in training pilots but in building a computer that no other lab could even dream of.

World War II provided the spark of interest and military funding that resulted in the first modern computers. There were not many of them in the world; the few that existed were almost exclusively housed in academic and military centers, and they were severely limited in function. One of the most prominent was the ENIAC, the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, typically referred to by the popular press in the late 1940s as the “Brain.” It was the first all-electronic programmable computer and, compared to human computational time, blazingly fast at calculating the accuracy of ballistic weapons, including hydrogen bombs. The machine, like all computers at the time, was massive, weighing in at more than sixty thousand pounds.

The machine Forrester and his team of men and women built weighed in at twenty thousand pounds and necessitated five thousand vacuum tubes. It cost only a third of Alice in Wonderland’s production budget, one million dollars, and utilized a far smaller staff, just a hundred and seventy-five people. These engineers were so clever that they were nicknamed the “Bright Boys,” although women were included in their ranks.

The first model, Whirlwind I, was completed on April 20, 1951, and it was sixteen times faster than any other computer then in existence. Forrester and his team had revolutionized the internal architecture of computers, so instead of using bit-serial mode, where the machine solves a single problem at a time, the Whirlwind worked on multiple inputs at once, thus calculating results more quickly. It was the forerunner of a new type of computer that used parallel computation and that would take over the industry in the years ahead.

The Whirlwind wasn’t just fast, it was also groundbreaking. The engineers built a display console, a primitive type of computer monitor, on which the calculations could be viewed in real time. Even more impressive, the technology included a light pen that, to outsiders, resembled a magic wand. When it was raised to the display console, it could point and draw directly on the screen using a photo sensor, lighting up individual pixels that were so small they were not visible to the human eye. In Burbank, Walt Disney Studios continued their work unawares, having no inkling that the technology being unveiled across the country was poised to radically alter their work and art.

While light pens worked their magic in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Mary was creating pixie dust back at the studio. Peter Pan, like Alice in Wonderland and Cinderella, was a recycled idea. The studio had worked on the adaptation more than a decade earlier, poring through J. M. Barrie’s text and sketching concepts for the large cast of characters, including Peter Pan, “the boy who wouldn’t grow up,” the Darling family, and a fairy named Tinker Bell.

Barrie introduced the character Peter Pan in his 1902 novel The Little White Bird. In the book Peter Pan flies out his nursery window when he’s only seven days old. He plays happily with the fairies at Kensington Gardens but ultimately plans to come home to his mother. However, when he returns at the end of the chapter, he finds his nursery window closed, with iron bars preventing his entry. When he looks through them he sees “his mother sleeping peacefully with her arm around another little boy.”

The themes of childhood innocence and painful rejection continue in Barrie’s 1904 play Peter Pan; or, The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up, later published as a novel in 1911. In this story, the character Peter Pan is no longer a baby but a child who, although old, has never become an adult. He listens outside the bedroom window of the Darling children as their mother tells bedtime stories. Peter wants Wendy, the eldest, to act as his mother and tell him stories, and so he invites the children to fly with him to Neverland. Here they have numerous adventures, meeting the Lost Boys, Peter’s gang of feral children; rescuing a princess named Tiger Lily, of the “pickaninny tribe”; and battling Captain Hook and his band of pirates.

Peter is not a particularly likable character in the novel. He despises adults so completely that he increases his respiratory rate because “every time you breathe, a grown-up dies; and Peter was killing them off vindictively as fast as possible.” He also murders Lost Boys: “The boys on the island vary, of course, in numbers, according as they get killed and so on; and when they seem to be growing up, which is against the rules, Peter thins them out.” Peter’s perspective on death is revealed in a scene where he confronts his own mortality; he says, “To die will be an awfully big adventure.”

At the end, Wendy, her brothers, and even the remaining Lost Boys all go home to the Darling parents. The book leaves Peter alone, befuddled and fulfilling the promise made in the first line of the story: “All children, except one, grow up.”

Designing the characters was a fairly straightforward proposition, with the exception of Tinker Bell. In the play, the fairy was represented merely as a glowing orb dancing around the stage. She had no human form and could not talk. To the artists at Walt Disney Studios, Tinker Bell was a blank slate, full of possibilities. In the early days of the feature’s development at the studio, numerous artists had tried their hands at depicting the fairy.

Dorothy Ann Blank, one of the early women of the story department, was the first to imagine the possibilities of Tinker Bell drawn as a fully formed woman. Dorothy had just completed work on Snow White, and so the fairy became an antidote to the princess. Whereas Snow White was meek and unassuming, Tinker Bell was saucy. “Tinker Bell is a surefire sensation,” Dorothy wrote to Walt, “for the animation medium can now, at last, do justice to her tiny, winged form and fanciful character.”

Bianca saw the fairy much the same way. She was the first to go to the studio library and check out Peter Pan, and in her sketches she depicted a sweet pixie with her golden hair in an updo, her body curved and womanly. In the original sketches made by the female artists of the studio, Tinker Bell strikes a balance between stereotypical extremes. She is neither the girl-child of Snow White nor the sexual fantasy of Fantasia’s centaurettes. Instead, she is a fully formed woman in miniature. Each female artist gave the fairy a gift; in Bianca’s hands, she became overtly sensual, in Mary’s sweetly feminine, and in Sylvia’s divinely colorful.

Tinker Bell’s impish yet sweet attitude is clear in Bianca’s sketches, where the fairy has a silly smile as she poses in front of a mirror while playing dress-up with Wendy’s belongings, or looks frightened by the children’s toys, or glows irresistibly above the three Darling children, who sit on clouds in a night sky. Bianca’s male colleagues at the time talked about Tinker Bell’s character in their story meetings, but most of them refrained from drawing her.

Bianca, unburdened by their hang-ups, was free to create, and at first Walt seemed to be listening. “Bianca has been working on some very colorful sequences in which Pan shows how he can call the fairies from their seclusion by blowing upon his pipes,” he said in a story meeting in 1939. In Barrie’s book, Tinker Bell is just one of a large community of fairies who live in Neverland. Inspired by the text, Bianca drew many different sprites, envisioning a complete world for the delicate creatures. She created imaginative sequences such as one in which Tinker Bell leads the Darling children underwater, and, with the help of pixie dust, they transform into merpeople and explore a sunken pirate ship.

Sylvia also worked on early concept art for the film, her paintings starkly different from Bianca’s and relying more on color than form to convey mood. She drew Wendy being crowned the Queen of the Fairy Ball by Tinker Bell, the girl’s eyes wide in wonder as the golden crown is lowered onto her head. Bianca worked on the sequence with her, imagining the fairies glowing like firecrackers around Wendy as they dance late into the night. Soon, however, the women who created fairies so successfully for Fantasia lost all hope for Peter Pan. The feature had been intended to follow Bambi, but with the overwhelming difficulties the studio faced in the 1940s it seemed unlikely ever to be made.

While Bianca, Sylvia, and Dorothy had all been dismissed, the studio retained their artwork. Unused concept art was stored in what Walt nicknamed “the morgue,” a term borrowed from police departments and newspapers for rooms where old materials, such as notes, evidence, or clippings, were stored. At the Walt Disney Studios, this room was underground, down a concrete corridor beneath the Ink and Paint building and behind a wooden door with MORGUE written in fancy gold lettering on it. Inside, bookshelves and file cabinets housed every scrap of material connected to the studio’s past work. Artists were free to wander in and out, doing research and gathering the material they needed for their projects.

When Mary began her work on Peter Pan, which Walt had finally green-lighted, she spent many hours in the morgue. She was reaching back in time to concepts and story lines that had been shaped by other female artists. Inspired by the bold vision of so many women before her, Mary began to chart her own passage. She painted a bright gold pirate ship sailing through the night sky, indigo clouds lapping like waves at its hull. Under her brush, green rolling hills flattened into the sandy beaches of Neverland, the entire island surrounded by a pink and purple aura. The darkness of the night sky overhead is punctuated by colorful nebulae. In Mary’s lagoons, mermaids feel the cool touch of a waterfall while resting on sunny rocks. Her imagination was unstoppable, and she also designed forest settings, a cozy grotto home for the Lost Boys, and, most unsettling, Skull Rock.

Captain Hook’s hideout is untouched by her usually whimsical color palette and instead stands gray and forbidding, the jaw of the skull opening into the cave within. The image would become iconic, forever tied not only to the original Peter Pan but also to the many future movies set in Neverland. Confronted with the products of Mary’s talent, the restrained Walt was unusually effusive, gushing over her seemingly ceaseless stream of ideas. Her work was almost too beautiful to be concept art, which was destined for the exclusive use of the studio’s artists and not meant for the public eye.

Mary’s paintings of indigenous peoples, however, did not deserve as much praise as they received. It was unfortunate that Retta Scott was no longer working as an artist at the studio. If she had been, she likely could have helped Mary refine her depictions.

One of the last projects Retta worked on there was a later-abandoned feature called On the Trail. Retta always took her research for a film seriously, and for this project she had spent long hours studying the Hopi tribe of northeastern Arizona. Committed to accurately portraying indigenous populations, Retta studied many texts, particularly a book called Hopi Katcinas Drawn by Native Artists. Her sensitivity is reflected in her concept art for the project, which is inspired by the original artists rather than coarse stereotypes.

In contrast, Mary’s paintings of the “Indian Camp of NeverLand” lack the refinement that study and application would have given them. They pull imagery from a mishmash of native cultures and have no fidelity to any real tribe. Nearly every stereotype of indigenous peoples is represented in the final film, including halting speech, tepees, feathered headdresses, and totem poles. Although Mary’s art alone would not have rescued the film from its racial caricatures, which are a central feature of the original play and book and were soon made even more pronounced by the animators, her edification might have at least softened their crudeness.

In 1951, in the midst of production on Peter Pan, a man named Eyvind Earle began work at the studio. The place was new and intimidating to the thirty-five-year-old artist whose background was in the fine arts and who had never worked in animation. As he wandered around his new workplace, he came upon a wall covered with small paintings. Over a hundred diminutive images filled the space, as exquisite in their squares as the truffles in a box of chocolates. Every single one had been done by Mary—she was already a legend at the studio, her name known to all. Earle stood before the images and felt deeply envious. Here was a woman who seemingly did everything: designed characters, fixed plots, selected color palettes, created scenery, and shaped the feel of an entire film. Studying the paintings, he thought, That’s the job I want at Disney.

Mary’s talent, advantages, and gender had always sparked strong reactions among her colleagues. Many seethed with resentment and jealousy, but for those artists able to appreciate her skill and work alongside her, the rewards were great. Marc Davis was among those who collaborated closely and successfully with Mary. Davis was sometimes known around the studio as a ladies’ man, not for his propensity to flirt with women, but for his mastery of the female form. Mary had worked with Davis on the title characters in Cinderella and Alice in Wonderland. Now they were brought together again for Peter Pan.

As an art director, Mary was designing every scene of the movie, although some would not make the final cut. Her work was wide ranging—in one scene she heightened the tension between Peter Pan and Captain Hook, while in another, she created the fantasy of a mermaid lagoon. Davis, as a character animator, had a more focused role. Mary experimented with color and concepts, but he was responsible for creating the final animation that would bring Tinker Bell and Mrs. Darling to life. It was the challenge of Tinker Bell that had brought Mary and Davis together, with Mary’s art informing Davis’s drawings. Neither was content with Tinker Bell’s superficial depiction in the book, and they resolved to make her more independent than any female character they had previously developed.

That representation, however, conflicted with the wholesome portrayal of women that was typical in the 1950s. At a story meeting, one of the men shook his head in disgust and then blurted out, “But why does she have to be so naughty?” Other story artists complained that her hips were too curvy and her personality too bold, the opposite of the demure and sweet Wendy Darling. Building on the work of so many artists before him, Davis infused Tinker Bell’s look with attitude, giving the playful fairy a loose bun with swooped blond bangs, green slippers with puffy white pom-poms, and a green leaf dress hugging her curves.

The one thing the artists didn’t have to worry about was Tinker Bell’s dialogue—she didn’t utter a single line. The only sound that came from her mouth was that of a tinkling bell. Since the fairy was denied words, Tinker Bell’s body language in the film was especially important. Davis called in Ginni Mack, a young artist working in the Ink and Paint department. Davis and the other animators crowded around Mack to sketch her lovely face and figure while she sat perched on a stool, posing and gesturing as directed. Professional actors, including Kathryn Beaumont, the woman who had modeled for Alice, were also brought in to film the movie in live action.

Male story artists and animators had long shunned drawing fairies, but Tinker Bell was turning the tide. Animating her represented an irresistible challenge, and her charming and impish nature was more interesting than the many docile female characters previously crafted at the studio. She quickly became a favorite.

Giving Tinker Bell the magical glow that Mary had painted on canvas seemed at first impossible on the acrylic cels. The solution lay in an unlikely source: the bile of an Asian ox. The studio employed multiple chemists whose role was highly creative. They experimented with various materials, becoming general problem solvers for the artists and creating paints that were completely unique to the Walt Disney Studio. By mixing gouache paints, a type of opaque watercolor, with ox bile, head in-house chemist Emilio Bianchi invented a sparkling glaze that would become essential to Peter Pan.

The foul-smelling paint was kept refrigerated, and the artists had to work fast when they used it, as the chemical could not be exposed to the air for long. Carmen Sanderson, an artist in the Ink and Paint department, spent long hours working on the three-and-a-half-inch sprite. To make Tinker Bell’s wings and body glow, she flipped the cel over and brushed the bile solution across the plastic. She used only a small amount and it had to be applied in a very thin layer. It was so delicate that if not glazed on properly, it pooled and formed ugly dark spots. When it was finished, however, Sanderson could admire its iridescent effect around the fairy’s body, the way it made her wings look radiant. The glow would combine with twinkling grains of pixie dust, each dot hand-drawn by the female artists, to make the fairy look utterly magical.

While the team concentrated on Peter Pan, it often seemed that Walt was somewhere else entirely. At story meetings, he frequently broke into discussions about plot and dialogue to discuss his favorite topic: the Mickey Mouse Village. He loved to talk about the train that would wind its way around the park, stopping at Main Street, a replica of a small town’s center that would be a relaxing place for people to sit and rest and that would have a string of stores selling company merchandise, a large movie theater, and a hot dog and ice cream stand. There would be rides too, carriages pulled by Shetland ponies, and even an old-fashioned riverboat. It was designed to be a trip back in time to an America that had never actually existed. Yet the nostalgia was intoxicating, not only for Walt but also for the many artists he was pulling in to work on the project, including Marc Davis. By 1952, the park that lived in Walt’s imagination had a new name: Disneyland. But as the park of his dreams slowly materialized, his animation studio started to falter again.