2

Cactuses and Succulents Outdoors

All plants have some particular claim to fame, and for succulents that is the overwhelming ability to survive in adverse conditions—especially in arid climes or times of drought. The vast majority of succulents come from rainfall-challenged locations that may also be plagued by extreme heat or cold. Coping with temperature extremes is a useful attribute, but the ability to hang on to every last molecule of life-sustaining water can border on miraculous.

In the gardening world, succulents are often lovingly referred to as “fat plants,” and their ability to store precious fluids for their survival has made them landscape stars for naturally dry, populated landscapes and areas in the throes of unnatural drought.

There are some plants (usually low-light growers) that are amenable to coming inside and doing quite well, but it’s a short list, and for succulents that list is even shorter. Indoor growing, while possible, comes with a litany of challenges to be managed in order to achieve a modicum of success. For this reason, growing succulents outdoors is by far the best-case scenario for healthy, attractive, and colorful succulents.

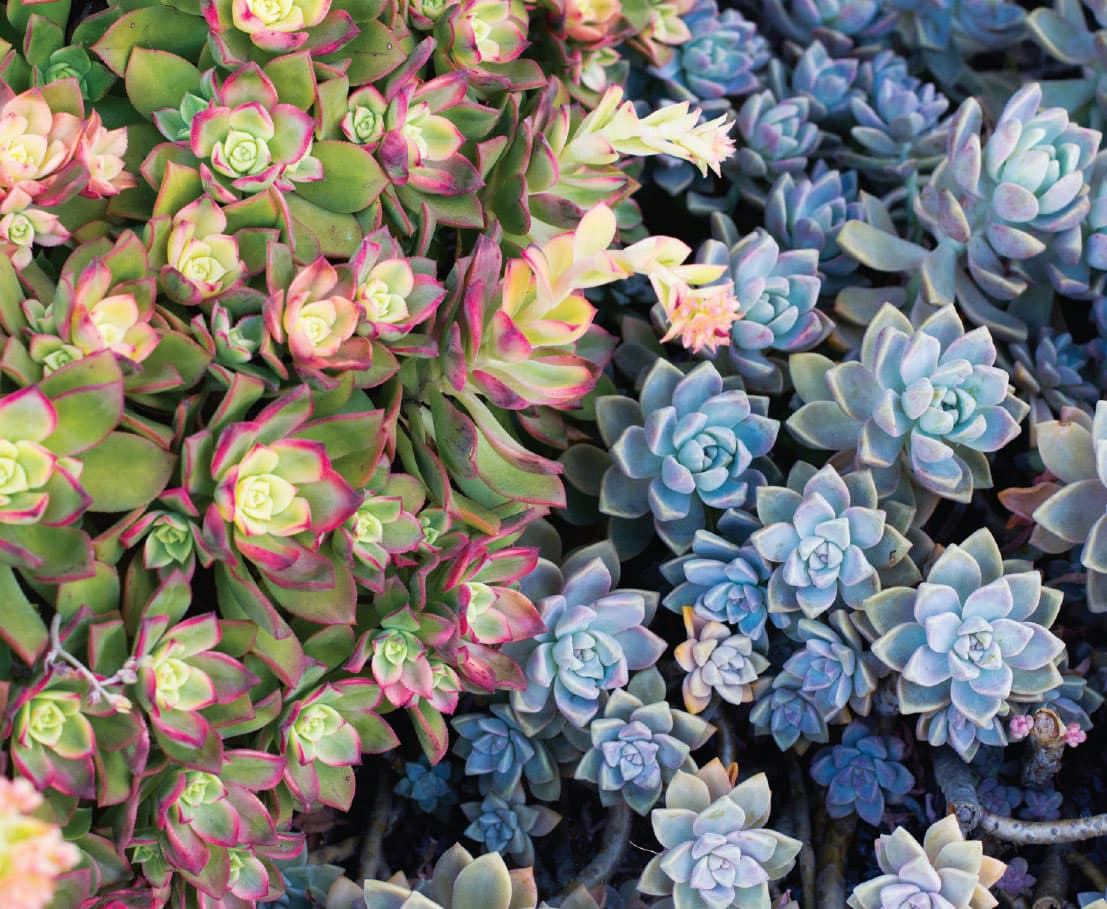

Colorful inflorescences are an added bonus to a well-grown mixed succulent composition.

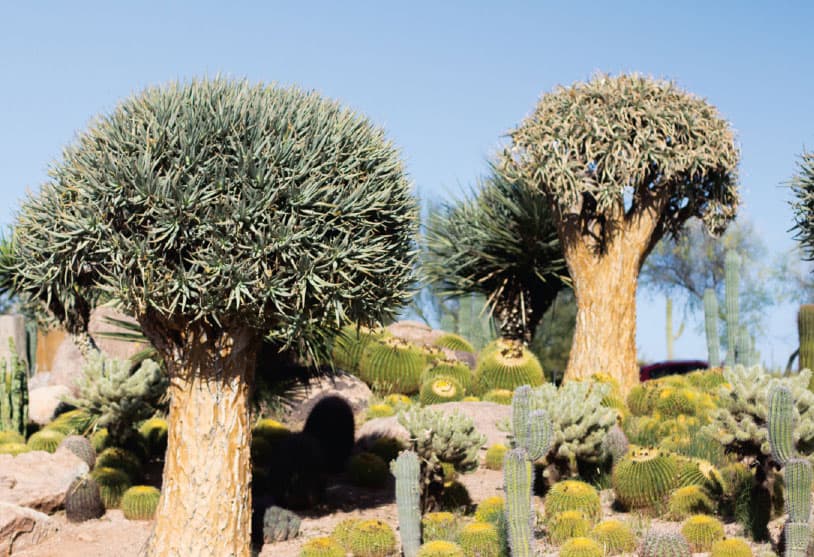

Very old tree aloes (Aloe dichotoma) with massive trunks and heavily branched canopies.

Tree-type euphorbias can serve as “nurse plants,” providing protection from the searing sun to the smaller, tenderer plants of the understory.

Succulents are available in a wide range of shapes and sizes to fit your landscape, from tall and tree-like species to low-growing groundcovers.

Cactuses and other succulents may thrive in dry desert conditions, but that doesn’t mean they can’t suffer from water deficiency. These plants don’t need to be watered frequently, but if you notice that they’re losing leaves, turning yellow, or collapsing on themselves, it might be time for a good soak.

Of all the aeoniums, Aeonium ‘Kiwi’ is one of the prettiest and easiest to care for.

Black as night, Aeonium ‘Zwartkop’ always stops foot traffic and turns heads.

Color options are endless as well—green is far from the only choice! Above, Graptopetalum is the bluish plant on the right; Aeonium ‘Kiwi’ is the pink-and-green plant on the left.

It is very common for many succulents in the harshest, most sun-scorched areas of the world to begin their lives in the proximity of a “nurse plant.” This is usually another type of hardy plant under which a young cactus or succulent begins its life and has the blazing sun tempered by an overhead canopy of leaves, stems, or branches. Cactuses may even take advantage of a nonliving “nurse,” such as a boulder, small hill, or mound that casts a shadow over the succulent for part of the day. But while this nurse is blocking the sun to some extent, it is only reducing the full-day, full-sun exposure by a fraction. So, planting in an area where the sun is relatively unblocked as it moves through the course of a day is ideal, followed by southern, western, and eastern exposures if dealing with an immovable object like a house, wall, or fence. A northern exposure is the least desirable and will be problematic and not particularly succulent-friendly overall.

Color combinations can be staggering too. Consider pairing the blue of Senecio mandraliscae with the near-black of Aeonium ‘Zwartkop’ and the screaming yellow of Sedum rupestre ‘Angelina’. Often there is an added spectacle in the fall and winter as temperatures begin to dip into the above-freezing but chilly range. Many succulents take on a whole new visage as the temperature stress forces them to adopt blushes of fiery to dark red and brilliant orange tones; many aloes are famous for this. The landscape design is up to the imagination. Look at perhaps using large groupings of boulders to create natural backdrops for the plants as well as provide natural crevices and hollows to plant in. Mimicking a dry streambed is a particularly eye-catching approach that is quite appropriate when designing a landscape composed primarily of cactuses.

Beauty can’t be denied when looking at a well-planted succulent landscape, and that beauty comes with lots of bonuses. Succulents are notoriously tough, as is obvious considering their natural habitats. Compared to the typical cottage garden or landscape full of perennials and tropical shrubs and flowers, their care is minimal. They are not heavy feeders, so fertilizing and poor soil are not a major concern. A feeding or two early on in the growing season (the warmer months of the year) using a balanced, all-purpose fertilizer is sufficient.

Watering is often misunderstood when caring for succulents. Because of their ability to survive inhuman aridity and heat, many succulents will go for an enormous length of time without a drop, all the while sacrificing bits of themselves to hang on. They may drop all of their leaves, collapse their stems (or whole bodies, in the case of many cactuses), even disappear completely, retreating to nothing more than a small nub on the surface of the soil that is attached to a still viable swollen root. They look absolutely horrible, if they even “look” at all! When a seasonal rain comes along, these decimated shadows of their former selves fill up like a camel at an oasis and get back to business. This is one reason why the cultivated succulent garden is superior to others. Unlike an English garden, for example, succulents are not going to wilt or fall over if you forgot to water last week, or even a couple of weeks ago. So celebrate the water savings, especially in drought-prone regions and where water costs are high.

Planting large swaths of spreading ice plants on outer perimeters of vacant property leading up to a dwelling, or even hedges of Crassula ovata (jade plant), Portulacaria afra (elephant bush), or Opuntia ficus-indica (beavertail cactus) strategically around buildings, can serve as an excellent firebreak. Being well over 90 percent water in most cases, they starve any fire of usable fuel and squelch an advance to endangered structures. The plants might take a serious beating doing the job, but they usually bounce back after all of the damaged parts are pruned out.

OVERWINTERING FOR COLDER CLIMATES

Regions that are naturally suited for succulent landscapes (along with various deserts) fall under a collective umbrella referred to as a “Mediterranean climate.” Succulents from South Africa, Madagascar, Mexico, and the arid locations of Central and South America feel right at home in this relatively perfect, frost-free paradise. The areas of the country that are fortunate enough to have Mediterranean climate conditions are truly spoiled when it comes to succulent growing outdoors, but areas that receive hard freezing and snow have fewer options for including succulents in their landscape. Most Sempervivum spp. thrive through cold periods and aren’t afraid of snow or temperatures down to −25°F (–31.7°C). This group is typically found growing in the colder and higher altitudes of Europe and doesn’t prefer a Mediterranean climate. There are many sedums that are equally freeze hardy, such as the Sedum acre, S. album, and S. reflexum (down to −25°F [–31.7°C])and S. rupestre, S. lineare, and S. hispanicum (down to 5°F [–15°C]). There are other succulents, including Yuccas, Agaves, and various cactuses, that are also suitable down to 0°F (–17.8°C), but research is the key. Although this book is not meant to be a cold-hardy succulent reference, the authors feel it important to let readers know that limited options exist. There are a number of sources dedicated specifically to these types of succulents and their companion plants.

The toothy Aloe marlothii (top) and an Aloe hybrid (bottom) frame three favorite jade plants from left to right: Crassula ovata ‘Gollum’, C. arborescens (silver dollar plant), and C. ovata ‘Hummel’s Sunset’.

The first step of protection for frost- and freeze-sensitive succulents has to do with water. Water expands when it freezes, so imagine plant cells as tiny water balloons—a water balloon filled to its absolute capacity will easily pop if frozen. If the balloon is only partly filled, it will expand with the freezing water and yet remain intact. The same applies to plant cells. As plants are entering dormancy in late summer or early fall, before the arrival of seasonal frosts or freezes, begin restricting their water. At this stage, the plants either are only slightly growing or have basically stopped altogether. Allowing their cells to partly empty gives them a better chance should a freeze hit.

A freeze or frost is considered “light” if the temperature is just below freezing and for only a few hours in the early morning. Under these conditions, the plants might be completely unfazed or suffer only minor tip burns. Covering plants the night before with a bed sheet, burlap sacks, or horticultural frost cloth (available in most good nursery supply locations) will increase the protection and success. Frost cloth in particular is available in various thicknesses and can offer an extra 4°F to 8°F (–15.6°C to –13.3°C) of protection. The edges of the various covers should be held down on their perimeters with stones or some other type of weight or device. Plastic sheeting is not a good choice as it doesn’t allow air circulation, increasing the chance of rotting from trapped moisture and humidity; it can also become a problem when the temperature rises too quickly for the plants to adjust. For extra protection from a longer or colder freeze, a string of Christmas lights laid on the ground, not in touch with the covering, will help raise the temperature slightly. In the case of taller plants that can handle a light frost but still suffer tip burn, such as frost-tender, columnar cactuses and columnar euphorbias, there is a simple and clever (albeit somewhat silly-looking) solution: Styrofoam cups placed over the tops of each of the columns or branches perform very well in protecting the tender growing tips. This obviously works for shorter plants as well when tip burn is the concern.

These recommendations are helpful in locations where frosts are light and brief and in the case of a rogue frost that’s not typical for an area. Keep in mind that locations suffering long, hard, and regular freezes have few, if any, options beyond growing freeze-tolerant plants or moving more tender plants indoors or into greenhouses for the duration.

This collection of color, shape, and texture is like a succulent fiesta.

Aeoniums, crassulas, and senecios make a colorful upright display.

A soft, unarmed, monocolored Agave attenuata serves as a backdrop for a bright and bold Aeonium ‘Sunburst’.

For an easy way to check moisture, lay a flat stone on the soil near your plant and check the underside periodically. If there is still moisture under it, it doesn’t need water yet.

If soil quality and drainage are concerns in your yard, consider using planters or raised beds. They easily allow you to fine-tune your soil mix. Window box planters are a wonderful no-fuss accent.

SUCCULENT PLANT CARE

Succulents and cactuses are continuing to grow in popularity, as a whole new generation of millennial gardeners is not only captivated by their beguiling beauty but also appreciative of their undemanding care. The survival adaptations of stems, leaves, roots, and trunks that enable the plants to store a life-preserving water supply has contributed to the incredible shapes of these plants. There is an important caveat to succulent culture, however: care often needs to be exacting, without much room for improvisation. Too much water or shade can quickly deteriorate the appearance of many succulents.

Watering Basics

Proper water and ample light are the main contributing factors to the success of succulents either indoors or outdoors. Succulent roots have adapted to optimize the uptake of water when it becomes available. In habitat, this characteristic is vital to a succulent plant’s survival. However, in cultivation, this beneficial attribute can have negative consequences. Because succulents are focused on storing water, they do not have the ability to quickly dispose of excess moisture if grown under wet conditions. In combination with cool temperatures, soggy roots begin to succumb to root rot and the plant quickly collapses into a sad, mushy heap. Because the propensity to decompose is always a reality, container succulents should always be planted in fast-draining soils or commercial cactus mixes.

While the perils of overwatering are real, so too is the pitfall of underwatering. Gardeners often think of the desert as an arid place devoid of all moisture. In reality, many desert plants have root systems that extend into areas many times the diameter of the main plant. So, in times of drought, these spreading root complexes have the ability to use heavy dews or mists. Restricted to a container with smaller root systems, succulents cannot take advantage of these additional sources of moisture. Insufficient water can actually cause the roots to desiccate and die. Succulent growers are responsible for providing the proper amount of water. Usually, the simplest way to water involves drenching the soil and allowing excess water to seep out the drainage hole of the container.

Don’t allow plants to sit in saucers of water. Any residual water should be removed. A general rule of thumb is, “If you are not sure whether to water a succulent, don’t.” Here is a convenient tip that might also help, even with plants in the landscape. Lay a flat stone, like a Mexican beach pebble, on the surface of the soil, near the plant. If there is still moisture under the stone when lifted, do not water. If the area is completely dry, it is time to water again. Remember that most cactuses and other succulents have an active growing period in spring and summer. Once the weather has warmed and other plants are actively growing, it is usually time to begin regular watering.

A nearly monochrome green planting becomes interesting when a variety of shapes are the focus

Graptopetalum is a fast and furious grower that readily creates crested or “cristate” growths, which can be removed and grown as their own specimen. This massive planting is sporting no fewer than six crests!

If there is still moisture in the top few inches of soil, your plants can probably go a bit longer before watering.

Bright yellow flower cones are quite the surprise coming out of jet-black aeonium rosettes. Large banks of gray-green Calandrinia spectabilis are just beginning to push out tall, graceful stems of deep purple, poppy-like blooms.

One of the biggest benefits to growing succulents outdoors is that you don’t have to worry about them getting enough light. However, some species may do better in partial rather than full sun to avoid sunburn.

It’s important that whatever kind of soil you use for your succulent, whether you’re buying a potting mix or amending the soil in your yard, has good drainage to avoid soggy roots.

Light Requirements

Some growing conditions that would kill other plants don’t phase succulents. Intense sunlight combined with extreme heat is a situation that most succulents can endure. Obviously, these settings are not usually found indoors and winter survival often depends on providing as much light as possible. South-facing windows are best for natural sources of light, but supplemental artificial grow lights can be used if such windows are not available.

When grown outdoors, many succulents look their best when protected from the searing rays of the sun. It is extremely important to bear in mind that sunburned leaves can easily occur when moving plants from an indoor location to an outdoor site. In order to prevent burning, plant leaves are covered with a waxy layer called a cuticle that thickens when exposed to sunlight, just as a tan protects human skin. Indoors, this cuticle thins out to allow in as much light as possible. Moving a plant directly outdoors can result in permanent scarring, especially on cactuses. Plants can be acclimated to sunnier conditions by putting them in partial shade and then moving gradually to brighter light conditions.

Sufficient light is critical for healthy succulent growth. Poor light can result in etiolated growth, especially on cactuses. Etiolation is a process that occurs with plants grown in insufficient light. It is characterized by long, weak stems; smaller leaves due to longer internodes; and a pale yellow color resulting from a lack of chlorophyll. This is nature’s way of increasing the likelihood that a plant will reach a light source, often from under the soil, leaf litter, or shade from competing plants.

Temperature

Although succulents are more cold tolerant than generally assumed, temperature is crucial to their survival. Freezing is a serious problem for many varieties. The ability of plant cells to store water also provides the ideal conditions for those cells to burst under freezing conditions, resulting in the demise of the succulent. Because a desert environment is often characterized by a distinct contrast between nighttime and daytime temperatures, most succulents thrive in colder nights, as long as it remains above freezing. Plants usually prefer daytime temperatures between 70°F and 85°F (21.1°C and 29.4°C) and nighttime temperatures between 50°F and 55°F (10°C and 12.8°C); however, they can survive brief periods well outside of these ranges.

When plants are grown indoors, a drop in temperature can often result in the initiation of flower buds. Locations next to windows often provide the ideal difference in temperature and can satisfy the cooling needed to trigger flowering. Christmas cactuses, Schlumbergera, are a good example of this. Many cactuses, especially those that are globe shaped, are far more apt to bloom if given a cool, dry period.

Potting Soils and Planting Mixes

Although light and temperature can be difficult to control, the type of planting medium that succulents are grown in is easier to manage, yet just as essential for healthy plants. Many retailers offer complete, fast-draining potting soils specifically designed for cactuses and succulents. If such a mix is unavailable, an all-purpose soil can be amended with fast-draining products such as perlite and pumice to make it suitable.

Native soils, where most succulents grow, are usually not high in nutrients, so organic material is not as important to their well-being. However, soils rich in microbes are healthier for all plant life. To create a suitable succulent soil medium, use two parts of a non-peat-based potting mix, one part perlite, and one part small-size gravel (like pumice). If gravel is not available, a 1:1 mixture of potting soil and perlite will suffice. It’s paramount to create a quick exchange of water and air in the root zone. Soils that stay wet for extended periods will result in the collapse of most succulent plants.

Fertilizer Needs

It is commonly known that succulents need to store water because of the harsh climates in which they grow, but it is less realized that this water-storing ability also allows for the storage of food. For this reason, succulents should be fed sparingly. An excess of food will be stored to the detriment of the plant. It is usually sufficient to feed plants during their growing season with a fertilizer that contains roughly equal proportions of nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium. Water-soluble foods are best and should be diluted to half the strength that is recommended on the label for other plants.

Day length begins to shorten as fall draws near and the weather begins to cool. This is when succulent plants enter their nonactive rest period. Do not feed plants during this stage of dormancy. There are a few succulents that are winter growers, and they should be fed at this time and allowed to go dormant as spring approaches.

This blooming aeonium is backed with a companion drought-tolerant Salvia leucantha.

Basics of Succulent Propagation

Collecting and gardening with succulents can quickly turn into a compulsion rivaled only by “orchid fever.” But unlike many orchids that can cost hundreds and even thousands of dollars to replicate, a huge number of succulents can be reproduced for pennies. Of course, there are many rare plants that are not cooperative and difficult to reproduce, such as frankincense and Welwitschia mirabilis of the Namib Desert. The golf ball cactus, Mammillaria herrerae, has been listed as one of nine of the most-threatened plants today. It is classed as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). However, it propagates easily from seed and, though threatened in the wild, this cactus has found a permanent home in domestic gardens.

Plant propagators offer hope for the preservation of succulents that are ravaged in the wild by poachers. Fortunately, most of the species that thrive in our homes and gardens are not only easily duplicated, but also fun enough to propagate for the whole family. Here are some of the simplest methods of propagation.

Growing from Seed

Because all cactuses and succulents are flowering plants, they should, in theory, be able to be propagated from seed. Nonetheless, due to the snail’s pace growth of some species from seed, other techniques are more practical. Cactus and succulent seeds are available from many online sources, but they can also be collected from plants in the landscape. Fresh seed usually germinates more readily than old seed, so a hands-on approach to seed gathering may produce the best results.

Plants that have been propagated by seeds or leaves fill these succulent liner trays.

1. It is important to start with clean pots or trays in which to sow the seed. As delicate seedlings germinate, they are especially susceptible to attack from harmful bacteria and fungi. If containers have been used in the past, it is a good idea to disinfect them with a solution of one part bleach to ten parts water. Also, because quick drainage is important, it is often advantageous to use shallow containers that are not deeper than about 4 inches (10.2 cm). Fill them with a planting medium that is equal parts potting soil and either perlite, sharp sand, or pumice. The majority of seeds can germinate in plain sand (not beach sand; it contains too much salt).

Note: Non-metallic planting trays can be sterilized in a microwave. Microwave the soil for about 90 seconds on full power. Allow the soil mix to cool and water it thoroughly. Let it drain, but not dry out completely. If the trays in which the seeds will be planted were not the ones microwaved, fill the propagation pots with the damp soil mixture to about ½ inch (1.3 cm) below the rim.

2. As in nature, most seeds will germinate best if sown in late winter to early spring. Scatter the seeds over loose soil and then press lightly into the mix. Lightly layering the soil with a fine covering of sand to hold the seeds in place is also helpful. Cover the seed trays with clear plastic wrap to hold in moisture and place the trays in a bright location, but out of direct sunlight. Minimum temperatures of 60° to 70°F (15.6°C to 21.1°C) are best for most species, but some tropical species may require warmer conditions (next image).

Fine gravel topping holds seeds in place for germination.

3. A significant number of cactuses and succulents will germinate within three weeks, but there are slowpoke species that can require as much as a year to begin growing. Germination times for specific varieties can often be found online. Once seedlings appear, remove the plastic wrap. The soil should not be allowed to dry out, but seedlings are fragile, so when it is time to water, moisten with very fine mists.

4. Once plants are about six months old, they can be transplanted into individual containers. As a general rule, cactuses can be transplanted when they are the size of a large marble and other succulents can be transplanted when they are about 3 inches (7.6 cm) tall. Gently lift the plants from the growing medium in the seed trays, set into the soil of the new container, and water in. Then top-dress the pot with sand, gravel, or pumice, which can help suppress the growth of algae and moss (next image).

Seed-grown cactuses ready to be moved to individual pots.

Propagation from Stem Cuttings

Propagation by stem cuttings is simple and practical. An unrooted cutting is very easy to establish. The objective is to get it rooted before it dries out too much, because cuttings can actually lose the ability to generate roots once they have become too desiccated. Cuttings taken at the beginning of the growing season will root the quickest. Here are some basic steps to follow.

1. Make the cut. Because pruning shears can crush tissues, it is normally best to use a sharp razor blade or knife that has been sterilized with alcohol to remove a cutting from the parent plant. A clean cut allows the cutting to heal fast enough to survive without water during the callusing stage. Strip leaves from the lower part of the stem (next image).

2. Dip the cut end in a rooting hormone. This is optional, but many rooting hormones also include an antifungal compound to discourage rot. Many wholesale growers report success using ground cinnamon as a cheaper alternative to an antifungal treatment. Just sprinkle it onto the cut end (next image).

3. Let the cutting callus over. During this period, the exposed cut of the succulent is allowed to form a protective callus. This process, which takes about a week to 10 days, is best done in a warm, shady spot outdoors. When a layer of dry, hard tissue has formed over the cut surface, the cutting is ready to plant. The purpose of this dry layer is to dissuade insects and diseases from entering the body of the plant (next image).

4. Prepare the potting mix. As with planting seeds, the mix should be composed of equal parts potting soil and either perlite, sharp sand, or pumice.

5. Select the proper size pot. Containers that allow for a couple of inches of growing should be adequate while the cutting is getting started.

6. Plant the callused stem cutting. Water immediately and then do not water until the soil begins to dry out. Taller cuttings may need to be staked until they root to keep them from falling over. After a few weeks, the succulent stems should have rooted enough to transfer into a larger container. Do not overpot; keep the size of the planter proportionate to the size of the root system (next image).

Multiplication through Leaf Cuttings

Even novice gardeners will find leaf cuttings to be an effortless way of generating countless numbers of new plants. Unlike most leafy plants, a wide range of succulents are very easily propagated in this manner. These are not actual “cuttings,” but are carefully removed leaves (with the exception of Sansevieria, which are cut leaf segments). Akin to stem cuttings, leaf cuttings are best taken at the beginning of the active growing season. Because of the ease and success rate, this is a great project in which to involve children.

The callusing process is similar to that of stem cuttings as described previously, but usually half the amount of time is required for the leaf end that was attached to the plant to callus over. Once callused, the end of the leaf should just barely be pushed into the soil, as this is where root formation will begin. The small leaves of many sedums are often just scattered over the tops of moistened sand in order to propagate them. Once a new plant has begun to form, the old leaf can be used as a handle to move the baby plant into its new pot.

Some of the groups of succulents that are easily propagated by leaf cuttings include, but are not limited to:

* Crassula

* Echeveria

* Gasteria

* Graptopetalum

* Haworthia

* Kalanchoe

* Pachyphytum

* Sansevieria (though variegated cultivars may lose their coloring)

* Sedum

These succulent stem cuttings with their lower leaves removed are ready for planting. Save the removed leaves—they can be planted too!

Instant Increase with Plantlets and Offsets

A number of cactuses and succulents form offsets, or “babies,” that develop around the mother plant. These can be removed and repotted by gently twisting them away from the mother plant. If the offsets are close to the ground, they will have probably already put out a small root system and are ready to be repotted. Numerous succulents, notably sansevierias and agaves, spread by means of underground lateral shoots. As these shoots give rise to new plants, the babies can be severed from the mother plant, callused, and replanted to produce an independent plant.

Some succulents are so teeming with a biological directive to reproduce that it can be a chore just to pick up after them. Included in this group are several Kalanchoe spp. that produce small plantlets (often bearing juvenile roots) along the edges of their leaves. These readily detach (they virtually seem to jump from the main plants) and are unbelievably able to create new starter succulents. One Kalanchoe plant will be surrounded by dozens or more juvenile plantlets that have fallen from the parent and rooted on their own. Bryophyllum is so prolific that its common name is mother-of-thousands!

Agave and furcraea plants grow for many years before finally flowering once and then dying. Small plantlets, called bulbils, form on the old flower stalks and will readily root to become new plants. Once plantlets have been removed from the main plant, they should be treated in a method similar to that discussed for rooting stems. Here is a list of some cactuses and succulent groups that can produce plantlets or offsets:

* Agave

* Aloe

* Echinopsis

* Furcraea

* Kalanchoe

* Mammillaria

* Sansevieria

This leaf placed on top of potting soil has begun rooting and forming a plantlet.

Leaf and stem cuttings will root and form plantlets without being planted or placed on soil.