CHAPTER 10

War Zones

Introduction

Crohn’s disease is a chronic, life-long, inflammatory bowel disease marked by relapses and remission. It is caused by a heightened response from the immune system to naturally occurring bacteria in the gut. Approximately 25 per cent of diagnoses occur in childhood and adolescence. A psychological consequence for this age group is an increased risk of anxiety and depression (Szigethy, McLafferty and Goyal 2010).

In this chapter I will describe the impact of Crohn’s disease on children and then outline some of the key themes in art therapy with children with chronic physical conditions.

This will be followed by a case study describing art therapy with a boy called ‘John’, aged 11, who was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease at the age of four. He was referred to art therapy in the NHS Children and Young People’s Service where I work because he was experiencing anxiety and anger problems. I will be exploring significant features of our work together and possible connections these have had with John’s experience of physical illness.

Crohn’s disease

In a review of the literature on inflammatory bowel disease, Szigethy et al. (2010) write about the impact of Crohn’s disease on children’s lives.

Physical symptoms can include pain in the abdominal area, bloody diarrhoea and fatigue. There are related difficulties with delays in physical growth and significant side effects from medication (Szigethy et al. 2010).

The psychological and social impact of the condition is extensive. Children can experience loss of independence, loss of control in their lives and of their bodies, including concern about body image, tiredness, physical weakness and loss of self-confidence. There can be social isolation and disruption of routines and roles with family and friends. Developmental factors, the severity of the illness and family functioning, especially the degree of social support for the family, can affect how well children cope with the illness. Children may experience feelings of anger, guilt, fear, shame and embarrassment. In response to treatment, which can include invasive medical procedures, children may become regressed, experience anger problems, become emotionally detached or experience dissociation. Emotional and behavioural difficulties may also be affected by treatments such as steroids, experiences of pain and loss of sleep (Szigethy et al. 2010).

Art therapy with children with chronic physical conditions

Reviewing the literature, I was unable to find specific examples of art therapy with children with Crohn’s disease or inflammatory bowel disease.

Two articles refer to art therapy with children with intestinal problems. Art therapist Anne Prager (1995) briefly describes how a boy aged 14, with intestinal disease, awaiting surgery in hospital, made a drawing of a maze resembling the intestines. She suggests that the drawing reflects the boy’s anxiety about the fragility of his intestines. Aleathea Lillitos (1990) writes about art therapy with children with intestinal motility problems, but her focus is on children in whom it is thought that their physical condition is caused by underlying emotional difficulties.

Szigethy et al. (2010) list other interventions to help children with the psychological impact of Crohn’s disease. These are: psycho-education, social support groups, cognitive behaviour therapy, narrative therapy (which may include systemic family therapy), hypnotherapy (which can help with relaxation and pain management) and ensuring that individual education plans are in place in school.

Despite the apparent lack of case studies describing art therapy with children with Crohn’s disease, there are many relevant examples of art therapy with children in hospital and community settings experiencing other chronic physical conditions, such as HIV, asthma, diabetes, arthritis and cancer. As with Crohn’s disease, children with chronic physical conditions are more likely to experience mental health problems (Gabriels 1999).

A strong theme in these examples is that art therapy is seen as a way of enabling children with chronic physical conditions to express and explore their feelings and experience some control, choice and achievement. This is often in the face of great fear and frustration (Malchiodi 1999a). As Rubin (1999) writes, children naturally use art and play to process stressful situations.

In the hospital setting Piccirillo (1999) describes artwork as an important physical outlet when other physical outlets are fewer due to illness.

Children can be active with artwork at times when they are required to be passive for medical treatment. Art materials are viewed as something familiar and comforting in the medical environment, and it is suggested that they can be distracting and help children to relax (Council 2003; Nesbitt and Tabatt-Hausmann 2008).

Making art can boost children’s confidence. Long (2004) writes that artwork can take on a talismanic quality in helping children to feel powerful and cope with frightening medical procedures.

Several art therapists discuss ways to use art to help children with physical conditions to communicate and feel understood. For example, Savins (2002) describes the use of puppets and using art as metaphor to help children of different ages to express and think about feelings of anger and fear.

Art therapists explore in different ways the content of artwork made by children with chronic physical conditions.

There are a number of art therapists who use structured tasks and assessments to understand the child’s needs and wishes, cognitive development, coping skills and understanding of their own illness and treatment. This information can be communicated to the medical team to inform a treatment plan and determine what supports should be in place to help the child and family (Council 2003).

Some writers believe that artwork can express aspects of a person’s physical condition on an unconscious level, suggesting that this can even anticipate physical changes and the course of the illness (Bach 1975; Furth 1988).

Malchiodi (1999b) describes how children’s experience of life-threatening chronic illness and medical procedures can be traumatic. In art therapy she writes that children may directly represent feelings about illness or traumatic events in their artwork, but suggests that they will often avoid consciously doing so because they feel unsafe, do not want to think about it or think it must be kept secret.

Goodman (1998) discusses the dilemma of not knowing how far spontaneous artwork might be related to the child’s experience of illness, and whether simply making art in itself has therapeutic and creative qualities that reduce anxiety. He writes about children who appear to use artwork to express anxieties and anger about their different chronic conditions but do not relate this to their illnesses verbally. Often it can have personal significance in ways that are not connected to illness. He explores the idea that the expression of traumatic experiences into artwork can help to transform them as they are put onto paper and can be seen and thought about.

There are examples of artwork being used to help children to describe and potentially alleviate their experience of physical pain (Long 2004; Unruh, McGrath, Cunningham and Humphreys 1983). It can also be used to help children to express feelings about their body and body image and the impact that physical illness and treatment can have on this (Malchiodi 1999a). For example, Favara-Scacco (2005) refers to the helplessness and emotional paralysis for children with cancer, who experience simultaneous healthy and destructive growth in their bodies. Treatment against the illness, which is a part of their bodies, adds to the emotional confusion.

Art therapists also recognise the social and familial impact of chronic physical conditions.

Several writers describe how group art therapy can help children to feel less isolated, share feelings and understand and cope with aspects of illness and treatment (Gabriels 1999; Piccirillo 1999).

Chronic illness and its treatment can place families under a lot of stress (Council 2003). In his work with children with asthma, Gabriels (1999) writes that the refusal of medications and treatments can be a problem, particularly in adolescence. This can become a battle in the family, where children assert their autonomy and parents can become increasingly anxious. He describes how family art therapy can enable the sharing of feelings and help parents to talk about feelings of anxiety, anger and powerlessness in the face of their child’s illness.

Case study: John

John, aged eleven, lived with both his parents and younger brother. He was first referred to our service when he was eight to help with anger problems at home and anxiety about his illness.

John had been diagnosed with Crohn’s disease at the age of four. He was treated with steroids and immunosuppressant drugs and was relatively symptom-free for three years. At seven he developed very painful abscesses and fistulous tracts (abnormal passages) running from the colon to perianal area and had to have an operation. He then had two six-week periods of liquid diets via a naso-gastric tube and missed a lot of school. He also had quite a bad reaction to one medication, involving high temperature and vomiting, resulting in him being admitted to the paediatric ward overnight.

By the age of nine John’s health had improved, although he continued to experience some pain and leaking and had to take medication orally every day and fortnightly through a painful injection. The medication weakened his immune system and consequently he was prone to infections and skin conditions. If there were any signs of illness he needed more frequent check-ups and blood tests. At different stages John refused check-ups and treatment, often vomiting, having panic attacks beforehand, and angry outbursts towards his parents. When he was ten his refusal of treatment led to deterioration in his health, narrowly avoiding an operation which would have resulted in him having to wear a colostomy bag.

These incredibly challenging and frightening experiences had a big impact on John and his family. By the time he was ten, John had become anxious about going to school, being worried about leaking, falling behind with work and missing out on sports due to aches and fatigue. He was concerned that he might not be able to eat, and as a result might lose weight, about having more treatments, and the possibility of having to have a colostomy. He could get very anxious about some of the medical language used in the hospital. He worried about pain, becoming ill again and dying.

John also avoided leaving the house (his mother described him as a hermit), and was anxious about the dark and the noise of the wind. He had thoughts that people might harm him and resisted going to the dentist, as he did not like things going into his mouth. It appeared that John also had fears about what was inside him damaging others. When his brother had a brief abscess on his bottom, John was worried that he had given his brother Crohn’s disease.

John often slept in his mum’s bed or wanted his parents to be there until he fell asleep. He could be anxious and demanding at home and his parents would give in to his demands. His parents were in a very difficult position, having to find a balance between essential care for his physical needs and nevertheless supporting his independence.

The family were initially seen by a social worker and then by a psychologist who worked with the family over a one-and-a-half year period. John struggled to engage in this and most of the work happened with his mother. This helped the family reflect on the impact the illness had had on them. There was also support and advice for John’s parents to try and help them strengthen boundaries and not let their concerns about his illness impact so much on their expectations of what he was capable of. There were some shifts, in that John started going out more and he returned to full-time education. However, he continued to have anger problems and anxiety, and could still avoid going out by saying he was feeling ill.

John was referred to art therapy to see if a more nonverbal, non-directive approach would help him: it was felt that using artwork might help John to express younger age feelings that he seemed to be stuck with, causing family tensions.

The following account is based on art therapy with John that took place over one year and consisted of 30 once-weekly one-to-one sessions.

War Zones: Part I

I first met John with his parents and I described how art therapy could be a place for him to express and explore his ideas and feelings through making artwork in his own time. I said this might include his feelings of anger and anxiety and his experience of illness.

John was a friendly, talkative and positive person. I felt that he had quite a lot of nervous energy. He talked in an animated way about his interest in history, World War II, strategy games and, at the time, Star Wars. He said that he made war drawings at home and at school. In many of our sessions John would go on to talk about family and school and sometimes about his frustrations and fears about medical treatment.

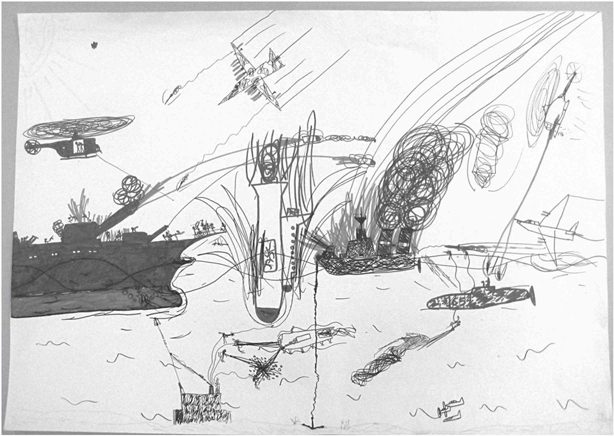

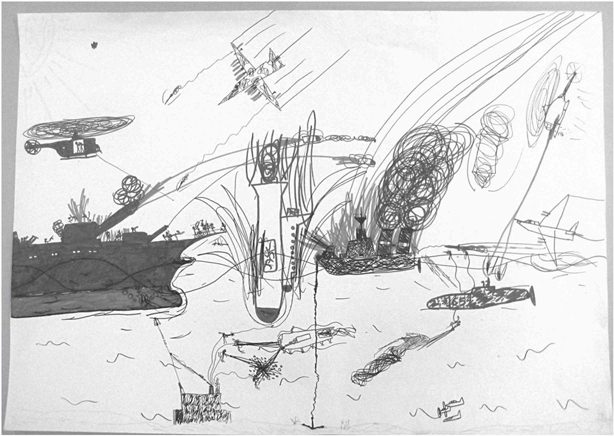

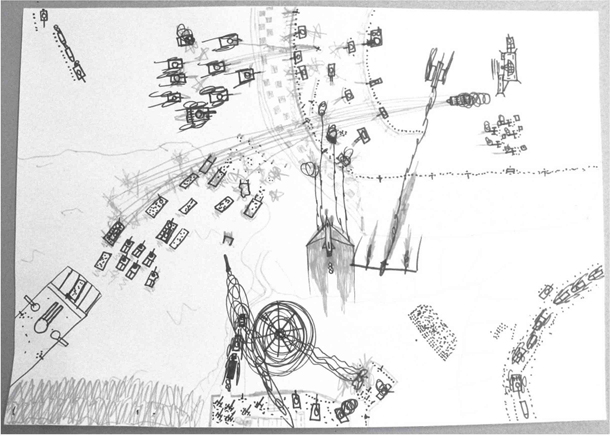

In our meetings John made many colourful drawings depicting battle scenes from various vantage points. Helicopters, planes, rockets, soldiers and various forms of weaponry attack each other. John said he liked to make drawings where almost everything got destroyed. In Figure 10.1, a pen drawing on A2 paper, vehicles, people and creatures at sea are flying and crashing in all directions in a scene of disaster. In Figure 10.2, another pen drawing on A3 paper, an expansive aerial view depicts walls and barriers bombarded with needle-like lines of fire, and burning planes in mid-air. A number of overt and covert territorial manoeuvres are going on. Some troops are hugely outnumbered. Other pictures depict battles where men are killed, often being torn apart at their midriffs. Referring to a scene in a film where a man was chopped in half, John asked whether you would survive this? In Figure 10.3, another pen drawing on A2 paper, John drew an underground cave network battle scene, which made me think of places inside the body, such as the digestive tract.

My impression was that there was some difference between how John was with me – friendly and agreeable, and what was going on in his pictures – danger, brutal killings and destruction, often on a massive scale.

As Goodman (1998) explores (see above), I was cautious about jumping to conclusions about possible connections between John’s artwork and his illness. John might well have been a boy who made pictures about war who happened to have Crohn’s disease.

Feinburg (1977) writes that between the ages of six and twelve it is common for boys to draw contests and battles with goodies and baddies as a way of exploring feelings of aggression, competition, power, competency and working collaboratively to overcome difficult problems and achieve tasks. They are not necessarily signs of emotional distress or conflict.

Figure 10.1 Sea battle (see colour plate).

Figure 10.2 Aerial battle (see colour plate).

Figure 10.3 Cave battle.

However, I found myself thinking about what this artwork might say on a more unconscious level, beneath the surface of John’s friendly exterior, about his physical experiences of illness, treatment and pain and his feelings about what was inside his body.

The pictures looked painful and contained a lot of destruction. I wondered if they could be an unconscious expression of John’s experiences of physical pain. Some images, such as Figure 10.2, show troops and tanks from opposing sides fighting across barriers. It brought to my mind the battle between the immune system and bacteria in the gut, which triggers Crohn’s disease (Szigethy et al. 2010). John’s body was essentially a battleground. His boundaries were being attacked by Crohn’s disease and by treatment.

The level of destruction and repetition of multiple scenarios of battles that neither side wins seemed to say something about living with an illness that doesn’t go away. Repeated imagery in art therapy can be a sign that someone is asking for help. It also reminded me of John’s vomiting before check-ups. I wondered if he was trying to get something out through his artwork. The repetition could also be a reflection of the traumatic impact that chronic illness and treatment can have. Malchiodi (1999b) writes that children who have had traumatic experiences may make repetitive imagery of themes such as violent or destructive acts. This can be an attempt to process and gain a sense of power and control over the experience.

The difference between how John was in the room with me, compared with what was happening in his artwork, made me think about what his experiences of treatment might have been like. I thought he would have had to be more passive and compliant, suppressing his rage and his wish to resist and defend himself. Were his pictures somewhere that felt safer to show this anger?

John’s enjoyment of being in control of destructive themes in the artwork also appeared to reflect the tendency in children to identify with the aggressor in order to cope with the experience of vulnerability and helplessness (Freud 1937).

The drawings portray battles between goodies and baddies. The baddies often outnumber the goodies. In two pictures there are goody and baddy double agents. I thought about how John, from the age of four onwards, must have struggled to understand that medical professionals and his parents who were taking him for treatment were goodies on his side, there to make him better, when his experience was that he was not protected from bad things such as intrusion and pain.

Shopper (1995) writes that children are likely to experience people who cause pain as bad, regardless of the good intentions behind the treatment. Adding to this confusion, Anna Freud (1952) describes how children may struggle to differentiate between the pain and discomfort caused by illness within the body, and the pain and discomfort that is caused by professionals treating the illness.

Furthermore, Anna Freud (1952) writes that children’s reactions to the experience of surgery and pain are influenced by the intensity of fantasies and anxieties connected to it. Surgery may reactivate earlier childhood fears of being attacked, damaged or castrated. If the child has aggressive fantasies towards the mother, an operation or treatment might be felt to be retaliation on his or her body by the mother. Experience of pain or restrictions as a result of illness and treatment could be experienced as a punishment for Oedipal jealousies or for having shown anger or exhibitionistic behaviours.

Alongside thinking about how surgery and pain may have disrupted and got in the way of everyday physical care and closeness between John and his mother, I wondered if John’s experiences of illness and treatment had reactivated the kinds of fears described by Anna Freud, so that earlier aggressive and destructive fantasies remained un-integrated. John appeared to have aggressive and omnipotent feelings, which were either acted out at home or projected onto the outside world, which he saw as an unsafe place.

His artwork seemed to be a site for the safe expression of these feelings. Referring to the writing of Edith Kramer, Council (1999) writes that artwork may depict fantasies that are too alarming or disturbing for the child to own more directly.

I waited until about halfway through our work together before I shared my ideas with John about possible connections between his artwork and his experiences of his physical condition and treatment.

John’s interest and knowledge of war as reflected in his drawings seemed also to be a refuge from the areas of his life taken over by illness, and important to his identity. I did not want this special area of his life, his identity as a war expert, to feel invaded by Crohn’s disease as well.

The activity of making these war pictures appeared to be therapeutic for John in its own right. He told me that he found making war pictures calming. John liked that I listened to him talking about his interests. He said he could concentrate in art therapy, whereas at home everyone was shouting at each other. John was able to link his own anger with war and destructiveness. He told me that he liked to play destructive computer games or look at war books with greater destruction when he was feeling angrier.

When I did talk about my ideas about John’s artwork, he listened to my comments, nodding before carrying on with his pictures and descriptions of war.

There were some signs from John that sparked an idea in my mind that if he could show some of the aggressive and destructive feelings expressed in his artwork more directly towards me, this might help them to become more integrated.

War Zones: Part II

Looking back to my very first meeting with John and his parents I had noticed that he had arranged furniture in a dolls’ house and was then using a Hulk toy action figure to knock all the furniture over. I also recalled that in the first therapy session John had tried some different art materials to the more usual pen and pencil drawings that he made at home and school. He made a painting and made some clay models. The painting looked like it was made by someone much younger. The clay models were very detailed and accomplished. From the second session onwards John returned to making his more controlled, fine line drawings.

John said he didn’t like the messiness and lack of detail of the paints. I thought that John’s ambivalence about making something that might feel more childish or messy could be typical of an eleven-year-old. He had an understandable interest in improving his art skills and techniques. However, I felt that the difficulty of containing messy paint might have been related to John’s fears of physically leaking, and also that his mixed feelings could reflect an anxiety about being less in control. What would happen if he were messy or showed aggressive feelings more directly in the room?

The interest in, but cautiousness about trying new things again brought to mind what John’s experiences might have been from before the age of four onwards. At a time when he would have been exploring the world around him, people from the outside world were instead exploring inside his body.

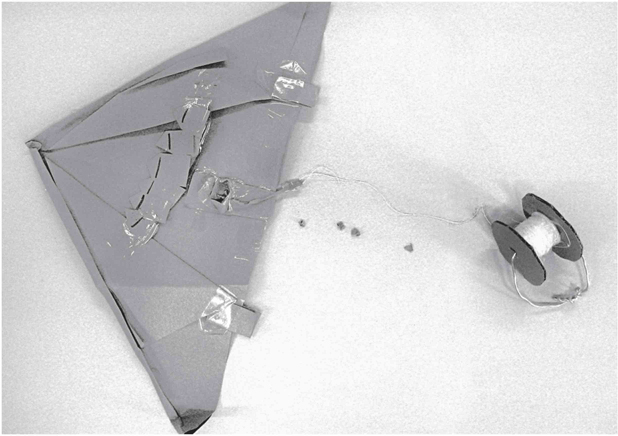

About halfway through our work together John had tried paints again, and in Figure 10.4 he tried some pastels for the first time. He described this as a different kind of battle scene. He was really pleased with the drawing and the fact that he had tried something new. I noticed that in the battle scenes we had been getting closer to the conflicts, often viewing them from ground level. Here two sides battle over muddy terrain. A powerful green tractor beam raises some of the enemy soldiers and equipment into the air. At first John said he was bothered by the smudginess but then he started to enjoy the effects. John made some humming noises while he worked and said he used to do this a lot when he was younger. He held up his hands in a playfully threatening way. They were brown and green from using the pastels and he said that he was a ‘zombie’ and ‘the Hulk’. I thought that John was feeling safe enough to get in touch with feelings from a younger age. I thought that by tentatively becoming a zombie or the Hulk with chalk on his hands, he was making a more physical connection between the aggression in his picture and aggression towards me.

Not long after, in a review meeting, John became angry and withdrawn when his parents talked about him needing to have some medical treatment. After they went away I remember feeling worried that John might not come back. I wondered what it had been like for him to show his anger in front of me for the first time. This made me aware that a lot of the time in the transference I was afraid of hurting John, and he was afraid of what his destructiveness might do to me.

Figure 10.4 A different battle scene (see colour plate).

John did come back. I talked about how I thought it was important that I had seen him angry for the first time. John made a very small paper gun while we were talking. I suggested that he could make something bigger if he liked. In the next session he had an idea for a competition. We would make paper aeroplanes and see who did the best designs and which planes flew the best, or in the most interesting ways. In several meetings John went on to make planes that carried paper bombs, and planes with various folds and cuts along their wings. He said that they were damaged but they might fly differently.

John also made a more sophisticated paper bomber plane. Figure 10.5 shows the underside of this plane, which had a wingspan of approximately 30cm. John worked on this over a few meetings with some help from me. He spent time carefully designing a compartment and doors to hold the bombs. We made a reel and cord, which we attached to the bomb doors to try and control when the bombs were released. I then placed paper planes that I had made on the target zone, a table across the room. John said the plane looked like it could fly, but it couldn’t. However, he believed it might. In fact it didn’t fly and it was difficult to control the release of the bombs.

Figure 10.5 Bomber plane.

I felt that the damaged paper planes said something about damage to the body, but also carried a sense of hope that this damage might be OK, or even make them fly better. Some of them did fly really well. The tricky operation to make the bomber release its bombs at the right time made me think about the operation that John had, and hopeless and hopeful feelings about wanting a body where he was in control of how it functioned.

The planes and bomber plane seemed significant because John was showing his destructiveness more physically in relation to me. He was having the experience that it was OK and even fun to do this. I don’t think that John felt punished or attacked for showing his destructiveness in this different way.

As we worked towards the end of our sessions John said he was feeling less angry, and his parents said he was a little less aggressive at home. His schoolteacher described him as more physical and ‘one of the boys’, whereas previously he had been more guarded.

Conclusion

It appeared that making drawings and objects relating to war, trying new things and finding ways to bring elements from these more directly into the room played a part in reducing John’s anger problems. Art therapy had enabled him to experience some feelings of control where he was in charge, develop his confidence and reduce his feelings of fragility.

Epilogue

War Zones: Part III

Towards the end of art therapy John had started to see a psychologist from the hospital to help him with anxieties about treatment. After some work with the family around boundaries, encouraging him to go out, and briefly trying family therapy in our service, the psychologist and John’s parents had asked if I could see him again the following year. They felt that art therapy had helped to lessen his anger. John’s mother had been unwell and had had to have an operation. John’s mood had dipped and he had been more aggressive at home.

When I met with John and his parents, six months after the conclusion of the 30 art therapy sessions, things had improved a little and I learned that he was more confident and played out with friends more. He was trying new things such as ice-skating and cookery. John was managing to go through with check-ups and tests and he had overcome his fear of the dentist.

In the beginning of this new stage of art therapy I could see that John had refined his drawing skills. War vehicles, explosions and killings looked more realistic. This increasing realism seemed to be another way for him to bring feelings about pain, death and destructiveness into sharper focus.

John asked me if I thought there would be a World War III? He seemed both excited and worried about this idea. Later in our meetings I said that I thought that he had been in a war with Crohn’s disease, with the medical professionals and with his parents. John again listened to my comments and nodded, and then resumed talking about his artwork and warfare.

John’s concern about whether World War III might happen made me think of his experience of not knowing when the Crohn’s disease might get worse again. I felt that his excitement was because it was through talking about and depicting war in his artwork that John was able to share his interest, his destructiveness and his experiences of illness with other people.

References

Bach, S. (1975) ‘Spontaneous pictures of leukemic children as an expression of the total personality, mind and body.’ Acta Paedopsychiatica 41, 3, 86–104.

Council, T. (1999) ‘Art Therapy with Pediatric Cancer Patients.’ In C. Malchiodi (ed.) Medical Art Therapy with Children. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Council, T. (2003) ‘Medical Art Therapy with Children.’ In C. Malchiodi (ed.) Handbook of Art Therapy. New York: Guilford Press.

Favara-Scacco, C. (2005) ‘Art Therapy as Perseus’ Shield for Children with Cancer.’ In D. Waller and C. Sibbert (eds) Art therapy and Cancer Care. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Feinburg, S.G. (1977) ‘Conceptual content and spatial characteristics in boys’ and girls’ drawings of fighting and helping.’ Studies in Art Education 18, 2, 63–72.

Freud, A. (1952) ‘The role of bodily illness in the mental life of children.’ Psychoanalytic Study of the Child 7, 69–81.

Freud, A. (1937) The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defence. London: The Hogarth Press.

Furth, G. (1988) The Secret World of Drawings. Boston, MA: Sigo Press.

Gabriels, R. (1999) ‘Treating Children who have Asthma: A Creative Approach.’ In C. Malchiodi (ed.) Medical Art Therapy with Children. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Goodman, R. (1998) ‘Talk, talk, talk. When do we draw? I. Definition of the problem. II. Talking and drawing with children.’ American Journal of Art Therapy 37, 2, 39–49.

Lillitos, A. (1990) ‘Control, Uncontrol, Order, and Chaos: Working with Children with Intestinal Motility Problems.’ In C. Case and T. Dalley (eds) Working with Children in Art Therapy. London: Routledge.

Long, J.K. (2004) ‘Medical Art Therapy: Using Imagery and Visual Expression in Healing.’ In P. Camic and S. Knight (eds) Clinical Handbook of Heath Psychology. Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe and Huber Publishers. (Original work published 1998).

Malchiodi, C. (1999a) ‘Introduction to Medical Art Therapy with Children.’ In C. Malchiodi (ed). Medical Art Therapy with Children. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Malchiodi, C. (1999b) ‘Understanding Somatic and Spiritual Aspects of Children’s Art Expressions.’ In C. Malchiodi (ed.) Medical Art Therapy with Children. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Nesbitt, L. and Tabatt-Hausmann, K. (2008) ‘The role of the creative arts therapies in the treatment of pediatric hematology and oncology patients.’ Primary Psychiatry 15, 7, 56–62.

Piccirillo, E. (1999) ‘Hide and Seek: The Art of living with HIV/AIDS.’ In C. Malchiodi (ed.) Medical Art Therapy with Children. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Prager, A. (1995) ‘Pediatric art therapy: Strategies and applications.’ Art Therapy 12, 1, 32–38.

Rubin, J. (1999) ‘Foreword.’ In C. Malchiodi (ed.) Medical Art Therapy with Children. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Savins, C. (2002) ‘Therapeutic work with children in pain.’ Paediatric Nursing 14, 5, 14–16.

Shopper, M. (1995) ‘Medical procedures as a source of trauma.’ Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 59, 2, 191–204.

Szigethy, E., McLafferty, L. and Goyal, A. (2010) ‘Inflammatory bowel disease.’ Child and Family Psychiatric Clinics of America 19, 301–318.

Unruh, A., McGrath, P., Cunningham, S. and Humphreys, P. (1983) ‘Children’s drawings of their pain.’ Pain 17, 385–392.