CHAPTER 14

Psyche and Soma

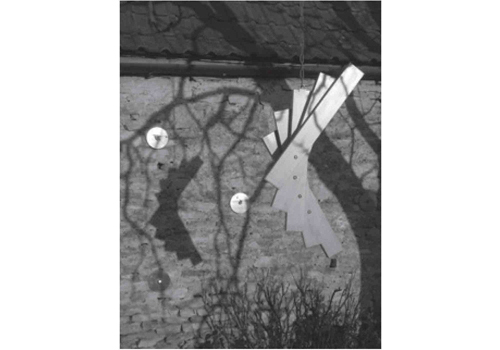

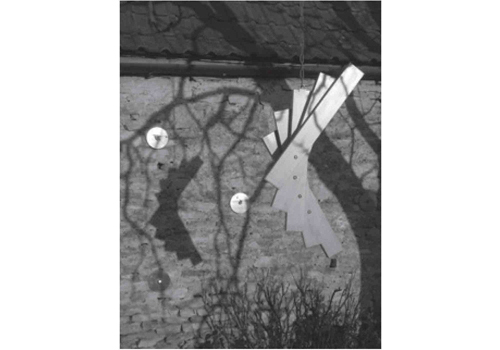

Figure 14.1 ‘SwingStak 2’ (2011). Maplewood and brass.

As a sculptor and an art therapist with two life-long conditions (rheumatoid arthritis and bipolar disorder), I have often wondered about the relationship between them. I have been an artist, a sculptor, all my life, from five years at art school into teaching, making sculpture and drawings. I had determined I would not join the gallery ‘scene’: I did not want to be an exhibiting sculptor. For me, art is spelt without a capital ‘A’, and has to do with spatial relatedness with people, as well as with self-expression. In the early 1970s, I had two major commissions where I could afford to work to human scale. My work has always been crafted, executed in both spasmodic and spontaneous ways, in short series or one-offs – until the next time that opportunity and the creative converge.

As an art teacher, I soon discovered through the children and young people I worked with, how the art room and studio can become an asylum: a safe, creative space. For them the everyday pressures of relentless academic demands could be put in perspective and kept in place for a short while, providing some respite. Over the years after I became an art therapist, art became the ‘application of art with people’. Training to me was, among many things, an articulation of the therapeutic relationship: with people, their art therapy images, the therapeutic space and myself. The work came to ‘fit’ me, and me it. It has felt that perhaps the person who became an art therapist was already there.

In 2001, I was formally diagnosed with bipolar disorder, which had prevailed unrecognised. To be given a formal diagnosis was important to me and my family after almost 30 years without identification of periodic distressing signs and symptoms. This meant that I could be prescribed lithium medication, which made a significant difference, smoothing and levelling off the ‘highs’ and ‘lows’ of my moods. Depressive phases were more easily identified than the less frequent ‘highs’. I have found it easier to recognise an impending phase of depression, but to be almost unaware when developing a ‘high’.

It is not uncommon for symptoms of mental illness to go unrecognised and untreated. Mental health services are badly underfunded, even though it is estimated that more than one in three people are affected in the course of a lifetime, and Welbourn et al. (2011) point out some of the issues:

Mental Health urgently needs a much higher profile in the Department of Health’s list of priorities for the NHS. While remaining largely invisible, it is an area of healthcare need which affects more than one in three people in the UK over a lifetime, costs 10% of the total NHS annual budget – more than cancer and coronary heart disease put together – and has been quantified as the largest single cause of disability in the UK, amounting to 23% overall. (Welbourne et al. 2011)

‘Wellbeing’ is a Department of Health buzzword, together with the slogan: ‘No Health without Mental Health’. But how much longer will the mental health needs of people in the UK continue to remain so inadequately and variously met?

In 2006 I was also diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). RA is a chronic, progressive and disabling autoimmune disease. According to the Rheumatoid Arthritis Society:

There are approximately 400,000 people with RA in the UK. It is a painful condition, can cause severe disability (varying between individuals and depending on how severe/aggressive the disease is) and ultimately affects a person’s ability to carry out everyday tasks. It is a systemic disease and can affect the whole body and internal organs, such as the lungs, heart and eyes. It affects approximately three times more women than men and onset is generally between 40–60 years of age, although it can occur at any age. So far, it cannot be cured, but now much more is understood about the inflammatory process and how to manage it. The prognosis today, if diagnosed and treated early, is significantly better than it was 20–30 years ago and many people have a much better quality of life in spite of having RA. (Panayi 2011, National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society.)

I have speculated about the dynamic between RA and bipolar disorder. I was afraid in the early days of developing RA that the seemingly endless, at times almost unbearable physical pain might trigger a bipolar manic episode. The depression end of the spectrum would perhaps be more apt. It seems to me that the physical is as powerful as the psychological and emotional; both create within each of us a reflecting balance and a functioning dialogue, as in Yin and Yang and/or psyche and soma. I feel it is important, when there are different, long-term conditions, as there are in me, that they should be seen, regarded and treated in relation to each other, not separately, both being within the same person. In the worst of times, this relationship has felt more like an internal, sadistic war than a phenomenon from which to learn. What kind of interaction is this between psyche and soma? What is the related dynamic between creativity and destructiveness? Both these life-long and/or progressive conditions evoke fear, anxiety and sometimes dread in members of my family as well as myself. I have childhood memories of my father’s description of enduring electro-convulsive therapy for his ‘manic depression’ without anaesthetic in the 1950s. Towards the end of a manic episode, potentially occurring every decade or so, I have experienced a sense of increased creativity, with a perception of heightened form, colour and energy. In my experience, this phenomenon is only fleeting and occurs during the ‘coming down’ phase when it includes an enhanced, but false, sense of clarity. It is the nearest to a positive experience in the whole episode. So I speculate about the possible links between creativity and bipolar disorder. Does the Creative have two masked, Janus-like faces?

To be an artist, a sculptor, energy, dexterity, strength, time and space by myself are needed. Now my physical energy is greatly reduced and dexterity often deserts me. Continuous physical pain, from its early development and treatment, has made it difficult to dream, to imagine creatively, to think outside myself and to find the energy to do very many things I had been used to doing in my everyday life. It was difficult enough to brush my teeth, never mind to use tools and art materials. I have felt frustrated, fearful and disappointed, and left with feelings of inadequacy.

I started out as a welder of mild steel and I still, largely, construct the little work I do out of wood, sheet aluminium, plastic/PVC or thick card. I don’t use plinths on which to site pieces of this work. However, small the scale, and whether vertical or horizontal in overall form, I try to relate the work as directly as possible to its environment. When a sculpture is placed on a base or plinth, it is immediately separated from the observer; it stands apart, making it less approachable and less intimately related.

Sculpture’s most important quality is its three-dimensional physicality and ability to relate immediately, in the round, to its surroundings and to whoever encounters it. Assembled sculptures are a ‘putting together’ and a ‘making fit’, the process sometimes involving a ‘pulling apart’. Constructing something is both an external making and an internal mending. In the same way as the spaces in-between (the voids) are defined by the material and the physical form, the ‘shape’ of the space between people may define and speak of the ‘form’ of their relationship. (Lewis 2011, p.210)

Art therapy offers a different way of seeing oneself, experiencing and approaching problems. Its three-dimensional possibilities, physicality, and materiality can offer different vantage points. In three-dimensional works, the question ‘What if? ’ can literally be seen from different angles and perspectives. (Lewis 2011, p.258)

Over 20 years ago I wrote: ‘I understand the term rehabilitation to mean a process that facilitates the optimum level of functioning for a person’ (Lewis 1990, p.72). It pertains to the notion of the resumption of everyday life, but in a new, adaptive way that is appropriate to each individual. This short commentary courts neither sympathy nor attention to myself. Some people might write this piece anonymously but I feel it is important to challenge both stigma from without, and shame from within. I have never felt it necessary, apart from in formal situations, nor been ashamed enough, to keep my condition(s) unknown to others – although I have sometimes felt concern at what others’ reaction(s) might be. I have come to acknowledge and to accept that my two conditions are part of who I am, for better or worse. The stigma generally associated with mental ill health remains; it is caused by ignorance and fear and is unconstructive, unhelpful and inhumane. Stigma mostly seems to stem from what is not understood. I would suggest that greater openness, together with an ongoing public health education programme, would be useful.

Here I have described in a limited way the person I was when I became an art therapist, and since. We all bring with us who we are, both positive and negative attributes and experiences. I think it is possible that the experience of having the two conditions of bipolar disorder and RA has contributed towards my being empathic with the people I have worked with – which is not to say that I might not have been empathic otherwise. Having been both an art therapist and a sculptor, I have had a sense of ‘making real’ and ‘mending something’ both in others and in myself.

If I had not become an art therapist, would anything I have said here have been different? I am sure that were it not for RA, I would possibly still be a practising art therapist. To continue to draw and to make sculpture is still an everyday aim. I remain the evolving person I have always been.

References

Lewis, S. (1990) ‘A Place to Be: Art Therapy and Community-Based Practice.’ In M. Liebmann (ed.) Art Therapy in Practice. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Lewis, S. (2011) ‘Sculpture: SAVL.’ ‘Vantage Points: SAVL.’ In C. Wood (ed.) Navigating Art Therapy: A Therapist’s Companion. London and New York: Routledge.

Panayi, G. (2011) ‘Rheumatoid arthritis: About RA?’ First published 2003. London: National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society (NRAS). Available at www.nras.org.uk/about_rheumatoid_arthritis/what_is_ra/what_is_ra.aspx. Accessed May 2011.

Welbourn, D., Bhugra, D., Adebowale, V., Jenkins P. et al. (2011) Letter to The Guardian, 21 May.