A Game of Anagrams

Three poets and a novelist play anagrams in Key West every Wednesday afternoon.

You will recognize the poets’ names. They are Paladin, Forester, and Drum. Leonard Drum, of course, not Robert Drum the physicist.

The poets are comfortable with each other, because all three have won both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. Two of them, Forester and Drum, have also won the Bollingen, but Paladin is not envious on this account. He recently sold his translation of Beowulf to Universal Studios for a saga film for a sum he commonly speaks of as having had seven figures (though, to tell the truth, two of the seven came after a decimal point), and so he feels able to console himself for that one deficiency and to wear handmade-to-order loafers.

The novelist, Chalker, has also taken a Pulitzer, as readers with good long memories may recall, for his novel Retorts. He is very thin and is rather a bad sport. And he smokes.

The other three have given up smoking. No. This is not literally true. What is true of one of the three self-proclaimed nonsmokers, Forester, is that he has stopped buying cigarettes. He has been known to strip two or three friends of their entire supplies in the course of an evening’s party. Since he has the illusion that he is “giving up smoking,” he particularly likes to borrow unfiltered Camels, so as to make his “last few puffs mean something.” During the anagrams games he borrows only one or two Marlboros from Chalker, unless he gets ahead. Poor old Drum has read up on the hazards of “passive smoking,” but he has much too good manners to ask Chalker and Forester to refrain. For his part, Chalker has noticed that Drum repugnantly turns his head away and holds his breath when a puff of smoke accidentally floats his way, and sometimes, when he, Chalker, is about to make a tricky change in one of his words or is going to steal someone else’s and may not want Drum, who is seated to his left and has the next turn, to be too closely aware of the move, he lets fly—perhaps he doesn’t even know he does this—with a puff out of the left side of his mouth, and Drum obligingly turns away.

Paladin weighs two hundred and eighty pounds and is, with his left hand, so to speak, a lexicographer. Besides his Beowulf and many slim volumes of poetry, he has published three dictionaries, one of Elizabethan English, one of Midwestern U.S. slang, and one of words with seven letters. This definitional avocation tends to make him positive about his challenges of the authenticity of some of the words the others make in the game, and the worst of it is, he is sometimes right. His triumphant demeanor makes those sometimeses so memorable that the others have come to give a bit more respect to his opinions than they deserve.

Readers of Forester’s poems will recall the profusion of fauna in them. The critic Bouvier has spoken of this poet’s exemplifying the possibility that a person’s name may come in the long run to shape his bent, and commenting on the woodsiness of Forester’s poems, he speaks of “the moral force of the man’s bestiary, set so lavishly among the trees.” The other three players have come to expect Forester to purloin their own little prize wordlets, again and again, and to rescramble them into the names of very obscure creatures—extant, extinct, mythical. It takes courage to challenge any of the ditsy zoa Forester trots out.

Lord knows what leaning Drum’s name should have caused in him—though, come to think of it, he is rather famous, in his poetry readings, for resonating his stresses, particularly where they fall on plosives in dactyls, and he is sometimes called a latter-day Vachel Lindsay, after that notorious word-thumper of the thirties. Emphatic though he may be at the podium, he is by nature mild and ultrapeaceable; a delicate flinch crosses his face when competitive sparks fly across the anagrams table, as they sometimes do in bright blue heat. But what really matters in the game is that Drum cares about what he eats and drinks, and the other players grow cautious whenever he shuffles the tiles in front of him into arcane names of cordon bleu delicacies, or of recherché mixed drinks, or of highly spiced Asian dishes that have somehow steamed their way into the dictionaries.

For several years in his boyhood, bad-tempered Chalker was dragooned by his conventional suburban yacht-clubby parents into racing in tiny sailboats of the class with the unfortunate name Wood Pussy on Long Island Sound. Drifting in the notorious calms on that body of water, he used to daydream—invariably, therefore, because of inattention, coming in last—to daydream of all the vast lore of the oceans. This has paid off in two ways. Always doing so badly in the races inclined him, later on, toward seeing if he could do a little better in life with the help of some minor cheating; and secondly, the richness of those daydreams, reinforced by bonings up in the Book of Knowledge and the Britannica, and by later, more sophisticated readings, has made him a big threat to the others in anagrams whenever the remotest nautical or pelagic possibilities turn up: THOLE, DIATOM, VANG, MIZZEN.

Very well. We now know something about the players’ specialties, or perhaps we should say their various favorite objective correlatives. Let’s sit by and very quietly watch as they gather for a game on a Wednesday afternoon around a card table in Forester’s living room, in his modest converted conch house in a compound on Grinnell Street. Mrs. Forester has shut herself in her dressing-room-cum-office upstairs, perhaps to distance herself discreetly from the noisy bonding these games always seem to generate. Paladin spills onto the tabletop a profusion of wooden letter tiles from a frazzled gray flannel bag that obviously once protected a silver something-or-other from tarnish; he long ago assembled the proper anagrams mix of letters by cannibalizing parts of two sets of Scrabble tiles, with their small numbers of valuation incised on them. Still standing at the table, the four turn all the pieces facedown and stir them around.

The first decision that must be made is where the players shall sit. Each turns up a letter; they then take seats around the table in the alphabetical order of their choices. Paladin is well satisfied not to be placed to the left of Forester, who is very good at the game, meaning that whoever plays after him is liable to be on starvation corner. Chalker, for his part, is delighted to have Drum once again on his left, or to leeward, as he thinks of it, in case a nicotine attack becomes necessary.

Now the players, flipping their seating-order letters facedown again, divide the mass of tiles into four more or less equal portions and slide them to the corners of the table, leaving the center free as their playground. Then each turns up another letter, to determine who goes first. Paladin draws an A, so he will lead off. The others have turned up r, L, and w. Those four letters remain exposed in the center space, and the players draw yet again, this time cupping the letters out of sight of the others. All is now arranged, and the four men are poised to start.

Before Paladin makes his first move, it may be helpful, for the sake of those of our kibitzing readers who are vague about how the game is played, to give an all too brief description of it (omitting minor quirks some obsessive players occasionally insist upon). Taking turns, picking out one facedown tile at a time and keeping its letter hidden from the other players, and perhaps drawing on whatever letters may be showing in a pool of discards in middle of the table, the players will try to form words of at least three letters and then build longer words by adding one or more letters at a time to change their meanings anagrammatically; they may alter their own words or, much better, steal and rearrange their opponents’ words. Thus bun may become burn, then brunt, then perhaps blunter, and so on. A player who has finished his turn deposits a leftover letter in his hand in the hope-giving reservoir of tiles at the center of the table. There may come a time when a player takes a chance on a complex combination of letters that he asserts (hopes? pretends?) is a perfectly good word; another asserts (hopes? pretends?) it is a perfectly good word; another player—here, as we’ve said, it’s apt to be the huge, didactic Paladin—may doubt its existence and challenge. The dictionary in use on a given day (Forester’s this afternoon is the newest American Heritage Dictionary) decides the issue, and whoever is wrong loses not only face but also his next turn. The player who winds up with eight intact words wins.

This bare-bones description of the game gives no idea of the interminable ponderings we will sit through with these players, the sighs, the yelps like those of little foxes, and the catacombic moans, and sudden eye-snaps of recognition, and tiles moved into place with trembling fingers, and, after thefts, victims’ tightened lips hastily modulating into halfheartedly admiring smiles at inspired outrages of robbery. There are also, it must be said, wonderful bursts of laughter that come from these four, for they do enjoy their follies.

Paladin makes his move. Without a moment’s hesitation, he forms the word WAR and places it facing away from him toward the center of the table. We innocent onlookers may wonder, why WAR? Why not a less confrontational word, RAW? Or LAW, for that matter, using the L that lies out there, instead of the R? How Paladin looms and glowers!

Never mind. Forester has drawn a secret E, and he steals WAR and makes it WARE.

Drum hums a brief tune expressive of doubt, and asks, “Shouldn’t that be plural?”

A scornful rumble, a sound as of tectonic plates shifting deep.

“Just wondered,” Drum says, shrugging.

Forester, not seeing anything more he can do after his next draw, puts an A out in the pool. Paladin will not have failed to notice that Forester has committed a rare goof: he could have changed WARE to AWARE.

When Drum’s turn comes, he picks up the A and L from the pool and adds his hidden E to make ALE. That’s all for him. Is he planning an Englishy menu?

Paladin has drawn an s, and he slides Forester’s WARE his way and makes it SWEAR. Again, we may pause to wonder at the aggression in the big man’s choice. Why not WEARS?

As the turns go by, a Q turns up in the reservoir, and surprisingly soon a u, and it is Forester who makes QUA.

In his next turn, Chalker draws another s, takes the SWEAR word away from Paladin, and spells WRASSE.

“Come again,” Forester says, outraged. “What’s that?”

“It’s a family of spiny-finned fishes,” Chalker of the seven seas rather smugly says. “There’s one species, right out here on the reef—you can sometimes see them from the glass-bottomed boat—that have the remarkable talent of being able to change their sex at will. Let’s say too few guys around, a female wrasse does a voluntary sex change. Just like that.”

“That’s what comes from swimming off Key West,” Drum says.

Paladin dryly says, “The word ‘wrasse’ comes from the Cornish, meaning ‘hag.’ ”

“Good God,” Forester says, having pulled far back from any thought of challenging.

While Paladin was making his etymological pronouncement, Chalker sneaked qua away from Forester and made it aqua.

At his turn, Paladin draws an h, and perhaps somewhat sedated for the moment by having one-upped Forester on “wrasse,” he fails altogether to see how the H might be used, along with the ale sitting out there in front of Drum. He drops the H out in the pool.

Forester’s eyes are hooded. He has an s. He reaches, with the absent look of a meditating Buddhist, for Chalker’s aqua, slowly drifting the letters over his way. Half the battle, in this foursome’s anagrams, lies in the air of confidence with which a player shapes up a word that is the least bit freakish, and Forester is a master of the sleepy, knowing look. He pulls the H from the middle, reveals his s, and makes QUASHA.

We now see a revealing flush—vulnerability? hesitation?—splotching Paladin’s face. He—even he—has often in past games been gored by one and another of Forester’s animals. He reads the word in the most noncommittal tone of voice. “Quasha.” There does not seem to be the slightest sound of a question mark in his delivery of the word.

“Came across it in Piers Plowman,” Forester says, with his bland air of the seminar instructor. “A pest in the countryside, as I remember. Something…something like a weasel. Stood as a metaphor, seems to me, for a deadly sin. I can’t remember exactly…covetousness, I think.” He stares Paladin straight in the eye as he names the sin.

Paladin has a faraway look; he seems to be riffling through some sort of large memorized pages in a book in his mind, perhaps those of Skeats’s Etymological Dictionary, in a frantic reach for a clue. You can read on his face that he hasn’t the faintest memory of having run across anything like a quasha in the Beowulf legends and that the word is not to be found, either, in his Elizabethan dictionary, during the compilation of which he dredged Skeats till the pages were ragged. Still, with this tricky Forester fellow…

“Oh, hell”—Chalker, furious at having lost a word and unable to wait for Paladin to come out of his bulky funk. “I’ll challenge that one. Sounds phony as a three-dollar bill.”

Drum, made uncomfortable by the bad vibes he feels hovering over the table, reaches for the dictionary. “No,” he finally says in a soft voice, not wanting to hurt Forester’s feelings. “I can’t find it….Not here.”

“That’s strange,” Forester says, looking not the least chagrined. “I could have sworn…”

“I do see ‘quassia,’ pronounced the same way,” Drum hurriedly offers, evidently hoping to avert a storm over Forester’s shameless invention. “Says it’s a drug, taken from the heart-wood of some kind of South American tree. Cures roundworm.”

Forgiveness does not make a showing on Paladin’s face. Chalker, however, is so happy at having got AQUA back, as a result of his successful challenge, that he, too, misses the possible use of the H now restored to the pool because of QUASHA’S collapse. He passes.

Gentle Drum slides the H his way and, in the spirit of a peacemaker, changes ALE to HEAL.

In the next few minutes, while other plays are being made, Chalker grabs HEAL and makes it LEACH, and on his next move, Paladin steals LEACH and adds two letters to make CHOLERA. AS we who are watching intercept a triumphant look that the big man throws Forester’s way, we may wonder again at the malignancy of Paladin’s choices. CHOLERA was clever, but why not CHORALE?

Forester, whose turn is next, gets that guru’s-trance look again. He has a B, and neatly sliding the brand-new word with his thumb and forefinger from Paladin’s stack to his own, he takes his time transforming the dread disease into BACHELOR.

Chalker exclaims, “Hey! That’s classy!”—making us wonder a little about his true attitude toward Paladin, for surely he must have noticed that though Paladin may only have lost a word for a disease, he looks now very much as if he’d contracted one. He seems seriously dehydrated.

Soon another interesting progression is unfolding. Forester has formed EKE, muttering, “That won’t have a long half-life.”

It doesn’t. Chalker, of course, makes KEEL, and Drum, his mouth perhaps watering, follows at once with LEEKS. Forester, with another H in hand, then does a rather brilliant SHEKEL.

Paladin, still a little pale but carefully keeping his voice calm, asks with an irony as heavy as his jowls, “What kind of beast is that? Quadruped, by any chance?”

“The male of the species,” Forester coolly says, “is called a buck, the female goes by the name of doe. I believe its natural habitat,” Forester adds, “is in the wilds around Beverly Hills.”

Drum, thinking this last crack a bit close to the bone, glances nervously at Paladin, who, however, remains copious in his silence.

The word SHEKEL holds its heat for two rounds, but then Paladin, having drawn a c, and yelping out a delighted “Ha!,” takes it and seems to aim HECKLES straight at Forester.

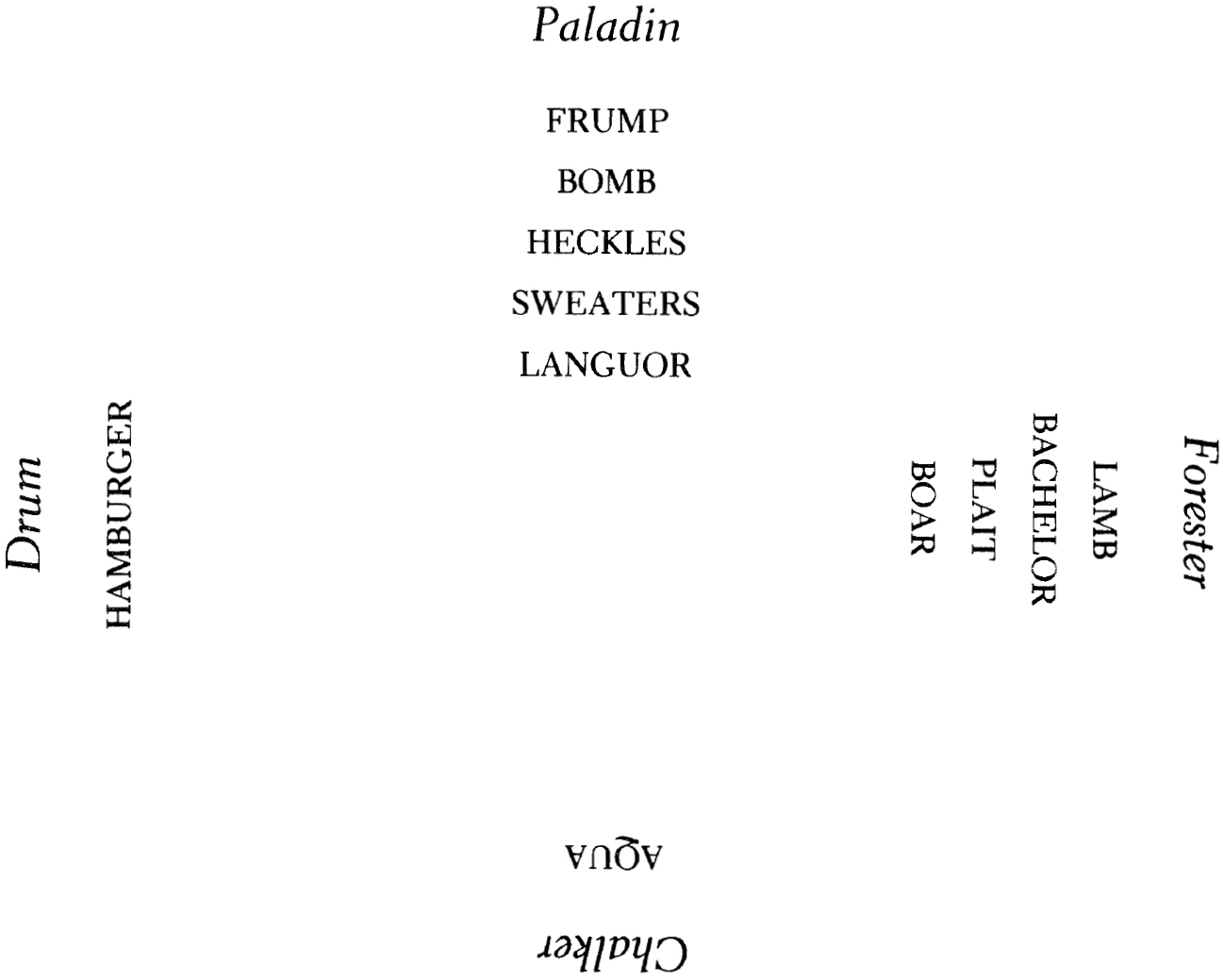

We who are watching have begun to wonder whether the Bollingen has weighed a bit more heavily in the balance of things than we had thought. Paladin, however, has been doing well in other plays we have not noted here, and at present the board stands as follows:

Forester’s LANGUR caused a bit of a flurry when he stole a RANG that Drum had made, but Forester sounded very firm, saying it was a long-tailed monkey with bushy eyebrows, and none of the others thought he would have the brass to invent two whole-cloth animals in such quick succession. The word went unchallenged, and a good thing too, because the dictionary would have made an additional monkey of the doubter.

Poor Drum has been cleaned out, but soon he gets his chance. Forester quite beautifully converts Paladin’s BEG (not Paladin’s kind of word to begin with, we would have thought) to BEGUM. Chalker, who seems to be catching something of Paladin’s virus of hostility, snatches BEGUM and, adding two letters, spells UMBRAGE. We now see from the aim and brilliance of Paladin’s eyebeams that he has a strong urge to take UMBRAGE, but in fact it is mild little Drum, with an H in his hand and an R from the pool, who slides the word his way and finally has something on his plate: HAMBURGER.

At this point, Paladin has a dangerous run of luck/skill. First he steals Chalker’s WRASSE and makes it SWEATERS; then he takes Forester’s monkey and makes it LANGUOR; and then he turns Forester’s PAT into PLAT. This last, he says with an assurance no one dares doubt, is a map of the sort a developer would draw, with land lots sketched on it.

Chalker, furious at the loss of his fish with its gift of ambiguity, points out to the others that Paladin must be stopped: he has seven words, just one short of victory.

Forester says to Chalker, “If you could spare a Marlboro, I might be able to do something.” Chalker gives him a cigarette and a light. In a few seconds, wrapped in a turban of blue smoke, Forester recaptures PLAT and makes it PLAIT, and then he robs Paladin of ROB and ducks back among his usual trees with yet another animal—namely, BOAR.

Here, then, is how things now look:

Chalker, whose face is dark, as we must presume, with bilious envy of Paladin’s and Forester’s stacks of words, has a moment—but just a moment, as we shall see—of recovered aplomb. He glances at Drum. He pauses then to shoot a big cloud of smoke out of the left side of his mouth, and as Drum turns away, coughing tragically, Chalker slides Forester’s PLAIT his way and turns it into TILAPIA.

There was a reason for the smoke screen. An interesting thing that happens toward the end of these games is that the minds of all four players seem to speed up, markedly so after one of them creeps close to victory. Adrenaline flows, just as in a footrace. An alert kibitzer, perhaps himself more mentally alert than usual, will have noticed that just before blowing his smoke screen, Chalker threw a quick glance toward Drum’s left hand, in which the latter held his supposedly secret letter rather carelessly. Chalker—who had no business doing this, and probably would not have, had he ever become Wood Pussy Champion of Larchmont Race Week—took note that it was an N. He also saw a second N among the rejects on the table. And with lightning speed he realized that with the two N’S, Drum could abscond with the beautiful word he was making. So poof went the cloud, and at once Drum’s eyes not only were averted, they itched and watered. And Chalker swiftly made TILAPIA.

Forester, all too aware of Paladin’s heavy breathing on his right, clears his throat in an interrogatory way. And at the same moment Paladin’s next wheeze has the distinct sound of a giant question mark.

“Gladly,” Chalker says, as if both men had actually spoken. “It’s an African freshwater fish. Amazing phenomenon. The female lays her eggs in Mr. Tilapia’s mouth, and he incubates them there.”

“My goodness,” Forester says, “you are frisky today, Chalks.”

In any case, no one challenges.

But look here! Drum has recovered with unusual alacrity. Perhaps Chalker fumigated him a little too late. He must have seen something out of the corner of a wet eye. For now, shyly but without hesitation, he takes the letters of TILAPIA one by one from Chalker’s array and places another eatable—bland enough it is, but Cubans are said to like it—alongside his HAMBURGER: a PLANTAIN. This is not one of Drum’s haute cuisine days.

We can see that Paladin has enjoyed this little drama. It’s clear that he is fully recovered from whatever ailed him after he lost CHOLERA. His cheeks are like McIntosh apples, his eyes have not a trace of brutality in them. He reaches across the table and, to the sound of a groan from Chalker, he steals AQUA and forms a word at the bottom of his pile. When he lifts his pudgy hands so the others can read the new word, QUADRAT, there comes a wild “What?” from poverty-stricken Chalker.

Forester can count; he sees how many words Paladin has. But he is a gentleman, and he says, “Yes, I’m afraid I know that word. A piece of land—it’s usually rectangular, as the name suggests, right, Pal?—that’s set aside for ecological or population studies. We could use a few more of them these days. Don’t you think, Chalks?”

Chalker swallows hard.

Paladin isn’t finished. He changes his own BOMB into MOBBED. He converts Forester’s latest animal into BROADS—for playfulness within reason is allowed in the game. The more Forester’s stack of words wanes, the more benign he becomes. “Broads,” he says to Chalker, “like those fishies of yours—till they change their minds, huh?”

As Chalker splutters, Paladin sweeps up a z and a T from the pool, and he tucks the I in his hand between those two letters. Paladin’s eighth word. So our game has suddenly come to an end, not with a bang but with a pimple.

Paladin releases a huge sigh, in sound not unlike that of a lighter-than-air balloon degassing to touch down in a soft landing after a glorious flight. Chalker is pale. Drum is sweet. Forester is indifferent. He knows they will play next Wednesday, and he’ll probably win. He usually does.