I was born in Southampton, Virginia, some where ’bout 1799. I ain’t got no ways of knowing my right age, ’cause I was born a slave. No mamma, no pappa, and I do not know if I have a sista or brother on God’s earth. If I do I would reckon they live right down the road from the Blows’ plantation, where I lived long time ago. Or maybe they was taken away and ain’t no telling where they is now.

Saying I do have some folks, I bet they wonder every day where I be. Just like I wonder about them. Maybe they do not exist at all. Could be they are only in my dreams. Could be they are the prayer that I pray.

It is also my prayer that if they exist they have not suffered the horror of slavery like me. I hope some nice white folks freed them years ago and they lives up north. Maybe they in a place far away like Canada. I do hope they are not still slaves back in Virginia, where my life with the Blow family started long time ago.

My Massa, Massa Peter Blow, told me he was born in Southampton, Virginia, ’round 1771. I ain’t got no memory of ever belonging to nobody other then he and his wife Miss Elizabeth Blow. It’s safe to reckon they bought me when I was nothing but a youngster. Maybe straight from my mamma’s warm body that I ain’t never laid my eyes on. I don’t know what she looked like. Lord, I do not even know the color of her skin. I do not know if she worked in the fields or in her Massa’s big house. Don’t know nothing. The Blows is the only family I ever know anything about and they not my own.

Miss Elizabeth say she married Massa Blow in the year 1800. Never asked her about where she came from. Maybe she from Southampton too. She was a little bitty woman with long blond hair. So long that she sat on her braid when it was not pulled up in a roll. Miss Blow didn’t say much of nothing and it’s ’bout right that Massa was surely the boss around there.

Them Blows was as nice as any white folks who owned your soul could be. They feed me well and didn’t beat on me like a dog. To my knowing they didn’t beat on none of they slaves. They gave me two pair pants and a shirt each year. Every other year they gave me a new coat come winter time. Don’t seem like much, but I hear tell of other slaves right down the road from the Blows’ plantation going naked until they was twelve years old. Some slaves never owned a coat in they life.

The Blows was not real rich white folks, but they had enough money to own a 860-acre plantation and five slaves: Solomon, Miss Hannah, William, Luke, and I, Dred Scott.

Solomon was the oldest slave, but he picked more cotton than William and Luke put together. William and Luke was brothers and they was bought by Massa Blow when they was young just like me. They did not know they mamma and pappa neither, but at least they had each other.

Miss Hannah was a pretty woman that none of the men bothered one bit. I do not believe she ever knew her folks neither. I reckon Miss Hannah was not much older than me, but she acted like an old, old woman. Maybe she was that way because she had to take care of everyone in the Blow family. I never saw them mistreat Miss Hannah. They just worked us both hard day and night.

It was just so much to do around that old place. I think most plantations was bigger, but the Blows’ home place is the only one I ever stepped foot inside of in Virginia. From the time my feet touch the floor in the mornin’ until I went to bed at night I did what the Blows told me to do. Whether it be washing, folding clothes, even fanning Miss Elizabeth when she was hot in the summer time, I reckon I done it all. Except the cooking.

Miss Hannah done all the cooking. She got to sleep in the big house too. I remember her hands most of all. Maybe because they made the best biscuits I ever eat in my slave life. Miss Hannah must have had a lot of white blood because she was a light-skin woman with hair as straight as Miss Elizabeth. All her hair was tucked under a head rag most of the time and she wore old clothes that Miss Elizabeth did not want no more. She was some kind of good to me. She was a mommy in some ways. I is going to always miss and love Miss Hannah for what she done for me.

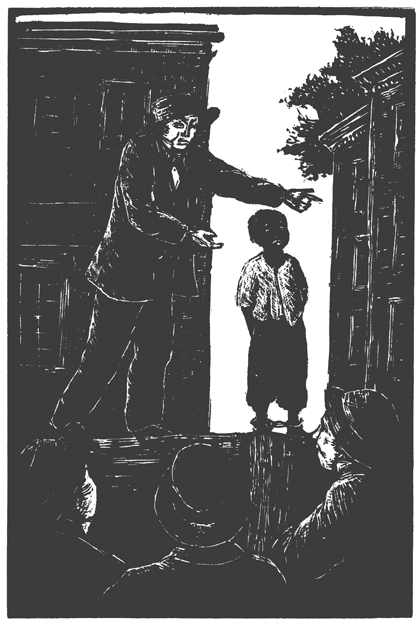

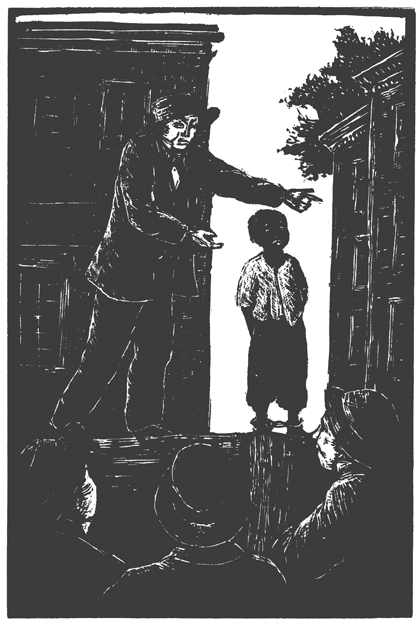

Sometimes when I was mad, I would say all kind of bad stuff ’bout Massa. Miss Hannah would say, “Hush up, boy, ’fore Massa sale you to another plantation. Hush, ’fore you get us all sold off.” I did like Miss Hannah told me and I never had any trouble from the Blows. I kept my lips so tight around the Blows that I never even got sent to the fields to work.

Them other men slaves worked out in the fields for Massa Blow until they couldn’t see each other come evening. The summer months was real hard for Luke, William, and Solomon. That is when they had to chop the weeds out of the cotton while the crops was young. The days was long and at night they would hardly sleep from the mosquitoes out in the small row houses where the fields hands slept. Come fall things was not better for fields hands. They picked cotton until dark.

No matter how little money Massa Blow made from the cotton, he planted some every year.

Times was hard, but Massa Blow kept us all working and fed.

I don’t know if he did it for us or himself. Honestly, Massa could not afford us slaves, but it made him feel like other white folks. It let the other white folks around Virginia know that the Blows wasn’t too poor. We was counted as they property just like they land or they cows in the fields. I can’t read one line, but Miss Hannah said that Massa even wrote our names down in a little black book that he kept in the kitchen drawer. Beside our names, Miss Hannah said he wrote how much we all was worth to him. She could not read either, but Hannah heard a lot of white folks talk when she was serving they supper every night.

In 1812 Massa Blow went off to fight in a war. Miss Elizabeth said it was the Sixty-fifth Virginia Militia that he joined and that Massa Blow was a lieutenant there for a few years. He left me in the big house to tend to Miss Elizabeth and they little children. Just me, Miss Hannah, and Miss Elizabeth was there in the house with the children. To me, a slave, I thought Massa was a crazy man to leave us there to take care of his folks. I will never understand how white folks that hold you as a slave could trust you with they wife and children. He trusted us more than I would have if I was a white man. If I was a Massa I would think them slaves wanted to take some revenge one of these days. But not Massa, he did not think like that at all. He didn’t think we would hurt a soul. It was like he knew we would not run off.

Massa was right. We had no where to run to.

When Massa came home, he went back to his business of farming and I kept up my business of the housework with Miss Hannah. Massa complained almost every day that things just were not going good with the crops. He said that money was low.

Lord, when it rained, the fields would be full of water. Most of the crops would drown in a day or two and nothing made Massa Blow madder than losing cotton, peanuts, or anything else he was trying to grow. Soon he started talking about us all leaving Virginia.

It musta have been fall when we moved because all the fields hands were called in from picking cotton so that Massa could give them the news. Massa Blow said we was moving to a new plantation near a place called Huntsville, Alabama. Massa told me and the other slaves that Huntsville was about four hundred miles from Virginia. There he said the land was higher and the crops would not drown from all the rain like in Virginia. I reckon I was about eighteen when Massa sold his farm and we all headed south to our new home place.

By then the Blows had themselves six children: Miss Mary Anne, Miss Elizabeth Rebecca, Miss Charlotte, Miss Martha Ella, Mr. Peter, and Mr. Henry. They was not mean children, just a little spoil. But they did not treat me too bad. I was older than them, but I played with them to keep them happy and out of Miss Elizabeth’s way round the house.

It was me and Miss Hannah’s job to do all the packing and loading wagons for our long trip to the new plantation. When we was done packing, we headed south. Miss Elizabeth, Massa, and the children was in one wagon, the furniture in two wagons, and the slaves and food in another one. To my knowing I left no folks behind.

The trip must have taken a month or a little over. We went through places I had never heard of ’fore—North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. My Lord, all the way there I would see cotton fields filled with slaves picking cotton from sunrise to sunset. Seem like the farther south we went the more slaves I saw. When we stopped along the way, I stayed close to the wagons. I stayed close to Massa Blow. I was scared that some overseer from another plantation along the way would take me for a runaway slave and I would end up belonging to someone else. Worse than that, I would be sent into fields every day to be worked like an animal. I heard tell it happen to many slaves while traveling south. Sometimes overseers would come in the middle of the night and steal slaves while they Massas slept.

When we finally arrived in Huntsville, me and Miss Hannah did all the unpacking and taking care of the children while Miss Elizabeth got rested up from the trip. Massa Blow put the fields hands to work right away. There was so much cotton to chop the weeds out of. The farm was not much bigger than the one in Southampton, but it was more land than house. More land for the poor fields hands to work in.

It did not take long for Massa Blow to figure out that farming was hard in Alabama just like in Virginia. So hard that we only stayed there two years ’fore Massa Blow came home one day and said we all was moving again. This time to a place called Florence, also in Alabama.

Things in Florence just was no better than they was in Huntsville, and after near ten years Massa Blow just got tired of one bad crop after another. In 1830 he came home and said we was all moving to a place called St. Louis, Missouri.

Massa Blow and Miss Elizabeth sat they children down and told them all ’bout this state of Missouri. They had eight children now. Two more boys, Mr. Taylor and Mr. William, was born in Alabama. I listened at the door so I would know something about this strange place that they was taking us to next. Massa Blow said it was a trading post that folks out there called “Gateway to the West.” Massa Blow said that they trade everything from furs to slaves there. I could tell by the way he was talking that my Massa was not sure one bit what he would do in that place, St. Louis. That scared me some kind of bad. If he did not know what he was going to do, then what would he do with five slaves? Soon we all would know.