Interactive

FROM MYSTREALM.COM REGARDING THE GAME MYST

You begin on the dock. As you walk to the stairs, note the marker switch. Flip it and all other marker switches on the island. There are eight in total, but you cannot reach the marker by the clock tower just yet. The remaining seven are accessible.

Their locations are: the Dock, Gear, Planetarium, Spaceship, Sunken Ship Model, Log Cabin, Brick Building.

Read Atrus’s letter to his wife that is conveniently lying on the grass.

Go back to the dock. You will see a door panel set into the hillside. Press it. Go inside …

The Interactive plot structure is one of the most unique plotting structures to date. Because of its infancy, it is hard to say exactly how far this type of writing will go, especially since it is so intimately tied into technology. If you are interested at all in narratology this is the structure to explore. (New York University has classes on this subject.)

While Interactive Fiction is most notably a part of video games, DVD edutainment, and role-playing games, it is also a part of the written novel. The following two novels are early examples:

• Marc Saporta’s Composition No. 1 is a fictional narrative consisting of about 150 unnumbered, loose sheets of paper. Readers are required to create a narrative themselves by shuffling the pages prior to reading them.

• In Hopscotch, Julio Cortazar creates two variations for reading his work. Readers must explore and work out possible connections between chapters.

As Espen Aarseth in Cybertext states, “The variety and ingenuity of devices used in these texts demonstrate that paper can hold its own against the computer.”

Print encourages us to see narrative events in a linear fashion. Words seem locked into changeless and closed lines. Interactive Fiction challenges this by forcing the reader to leave open the possibilities of narrative flow. Each event can have several meanings and several courses of action may result.

In Hypertext 2.0, George Landow says Aristotle pointed out that:

Successful plots require a probable or necessary sequence of events. But removing a single probable or necessary sequence of events does not do away with all linearity. Linearity, however, then becomes a quality of the individual reader’s experience within a single text and his or her experience follows a reading path even if that path curves back upon itself or heads in strange directions.

Interactive stories are multidimensional, infinite, inclusive, and untamed, which is a more open-ended matriarchal type of storytelling, completely beyond Aristotle’s time of pure patriarchal storytelling. There is never just one way of creating a work of art.

Interactive Fiction challenges traditional literary structure and forces the writer, as well as the reader, to question accepted storytelling rules. Again, in Hypertext 2.0 Landow says, “Looking at Poetics by Aristotle, a discussion of (Interactive Fiction) means one of two things: Either one can simply not write Interactive Fiction (and Poetics shows us why) or else Aristotelian definitions and descriptions of plot do not apply.” Indeed they do not. Interactive Fiction is, by its very nature, poly-sequential and in a completely different category. There are sequences, but none are necessary!

Michael Joyce, professor at Vassar College and award-winning novelist, say:

[Interactive Fiction] replaces the Aristotelian curve (of beginning, middle, and end) with a series of successive, transitory closures. … The core of [Interactive Fiction] is not to get to some secret ending. It’s more about successive understanding of kaleidoscopic perceptions that I think characterizes any art and makes our lives worthwhile.

Interactive Structure

The best way to teach Interactive Structure is to look at the way video game designers approach the subject, which is what I will do here. Most of you will probably want to combine Interactive Fiction with technology anyway.

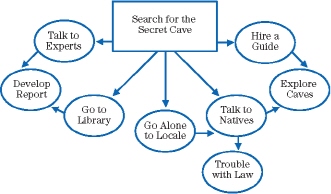

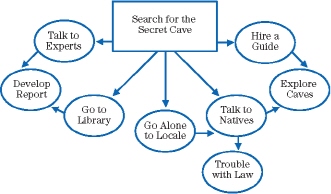

Video game writers call this type of writing Branching. It is like creating a flowchart instead of an outline for your narrative. Each branch is a different path for a character to follow.

For wonderful in-depth information on all of the following, see Writing for Interactive Media: The Complete Guide by Jon Samsel and Darryl Wimberley. Eastgate Systems publishes highly regarded Interactive Fiction and Storyspace software to design them. Also read James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake for a wonderful example, and play the computer game Myst.

Bear in mind that Branching at its best is motivated by inner urges. It should be a path or area for a character to explore, not just one standard choice among many. Joyce says, “[Interactive Fiction] is about the inner possibilities of the story. … We choose our lives by inclination, by urges, by happenstance or seductions.”

For example, many of us would rather swim a hundred feet in a calm lake than run five miles uphill, but someone who almost drowned as a child would make the opposite choice. That, then, is an inner-directed choice or “branch path.”

The Interactive Structure is driven by the reader. The reader decides where to go and what to read or do next according to his own preferences. Since there is usually no clear three-act beginning, middle, and end with an Interactive Structure, I will not even use Act I, Act II, and Act III as reference points. It would only confuse the explanation. As you will see, the move away from narrative structure requires much more work from the writer. This is why it is a good idea to know a lot about Traditional Structure before you go breaking all the rules.

Interactive Elements

TRADITIONAL ELEMENTS

All the traditional elements can be found in an Interactive Structure, though instead of two Turning Points you have many Decision Points. It’s all up to your imagination, preference, and goal as a writer.

• Setup

• Mood or Tone

• Hook, Catalyst, or Inciting Incident

• Serious Problem and/or Goal

• Villain

• Main Characters:all of them introduced here

• Problem Intensifies

• Temporary Triumph

• Reversal

• Dark Moment

• Final Obstacle

• Climax

• Resolution

NEW ELEMENTS

According to Writing for Interactive Media, there are “ten geometric design structures within Interactive Fiction.” They are:

According to Writing for Interactive Media, there are “ten geometric design structures within Interactive Fiction.” They are:

1. SEQUENTIAL WITH CUL-DE-SACS: The entrance to the branch or decision point is also its exit.

2. BRANCHING: This consists of traditional branching where the user is presented with several choices at predesignated “forks in the road” and extended branching where the story line has forks in the road, after forks in the road, indefinitely.

3. CONDITIONAL BRANCHING WITH BARRIERS: The reader is forced to solve a puzzle, for example, before she can move on.

4. CONDITIONAL BRANCHING WITH FORCED PATHS: For example, a user is supposed to find a crystal; she has two choices, but no matter which choice she makes she will find the crystal. Both choices have the same forced outcome.

5. CONDITIONAL BOTTLENECK BRANCHING: Branches of the story are brought back into the spine of the story to rein everything in.

6. CONDITIONAL BRANCHING WITH OPTIONAL SCENES: This is an edutainment where one can click on a link to gain information but must return to move forward.

7. EXPLORATORIUM: This allows the reader to stop the main story and explore another world.

8. PARALLEL STREAMING: This occurs when various states or paths exist simultaneously at various levels.

9. WORLDS: This is when two or more environments are interconnected by a common thread and have a series of predefined events.

10. MULTILINEAR OR HYPERMEDIA: This encompasses every type of user path imaginable or no path at all (think of the World Wide Web).

Temporary Triumph and Reversal, as well as other elements, may only be used in one sequence of the story depending on the decisions made by the reader. In other words, you will most likely not need to use them in every sequence or Decision Point that branches out on its own path.

Temporary Triumph and Reversal, as well as other elements, may only be used in one sequence of the story depending on the decisions made by the reader. In other words, you will most likely not need to use them in every sequence or Decision Point that branches out on its own path.

Instead of two Turning Points you will have many Decision Points. Depending on your goal you may:

Instead of two Turning Points you will have many Decision Points. Depending on your goal you may:

• have the reader decide where to go next based on the options you give (for example, go after a specific character’s goal)

• have the reader decide where to go next based on the options she gives herself (for example, shuffling scenes around and putting them back together)

• have the reader decide if he wants to select a link to learn something new (for example, click a link to read a character’s bio)

• have the reader perform some task (for example, edutainment pieces that teach; add up numbers to find the next page to turn to or solve a riddle to move on)

If you are writing an Interactive story for the Web, you would highlight selected text that a reader can choose to click on. Once clicked, any of the above can happen.

If you are writing an Interactive story for the Web, you would highlight selected text that a reader can choose to click on. Once clicked, any of the above can happen.

Keep the choices as personal as possible. Think about all the different types of people out there; maybe even read a bit about psychology. Use this to develop your characters. Perhaps each one of your characters has a different psychological makeup and the reader can select which character to follow.

Keep the choices as personal as possible. Think about all the different types of people out there; maybe even read a bit about psychology. Use this to develop your characters. Perhaps each one of your characters has a different psychological makeup and the reader can select which character to follow.

Interactive Fiction is limited only by your imagination. You can do whatever you want, but keep in mind if it seems too easy you are probably doing something wrong! In many ways this structure takes the most planning of all structures.

Interactive Fiction is limited only by your imagination. You can do whatever you want, but keep in mind if it seems too easy you are probably doing something wrong! In many ways this structure takes the most planning of all structures.

QUESTIONS

• What type of Interactive Fiction will you write (video game, role-playing, edutainment, print, Web, or something new)?

• Will you use Branching? How many branches leading to alternate stories or situations will you have?

• Will you use Decision Points?

• Will you do an experimental piece, similar to Saporta’s Composition No. 1?

• How many characters will you have? Will they be drastically different? Approaching situations differently?

• Most importantly, who is your audience? (Interactive Fiction games are equally made for all age groups from kids to teens to adults.)

EXAMPLES

Myst, UBISOFT ENTERTAINMENT

Myst is the number-one selling CD-ROM title of all time. Myst sends you to fantasy worlds where you must solve puzzles as you seek to unlock the secret of ages past.

Composition No. 1, MARK SAPORTA

This book is a 150-page story consisting of loose sheets of paper to be shuffled around to create a narrative.

Finnegans Wake, JAMES JOYCE

This experimental novel is the story of a man, his wife, and their three children. The novel presents history as cyclic, and the book begins with the end of a sentence left unfinished on the last page.