MULTIPLE PERSPECTIVES ON ENGINEERING DESIGN

David Radcliffe, Purdue University

Learning Objectives

So that you can provide students with a robust and holistic appreciation for the engineering design process, upon reading this chapter you should be able to

•Describe the act of engineering design from multiple perspectives: as a process, as critical thinking, as learning, and as a lived experience

•Articulate major factors that lead to successful engineering design

INTRODUCTION

Design is a defining characteristic of engineering. Theodore von Kármán, the Hungarianborn physicist and engineer, is reputed to have said, “Scientists study the world as it is; engineers create the world that never has been.” Engineers share this creative endeavor with many other design professionals, ranging from fashion and graphic designers to architectural and industrial designers. While engineers and engineering educators often define engineers as problem solvers, this epithet fails to adequately capture the full richness of what it is to engineer (Holt et al., 1985).

Engineering design is a recursive activity that results in artifacts—physical or virtual. These may be new to the world or simply variants on already existing things. Design involves both the use of existing information and knowledge and the generation of new information and knowledge. For engineers, designing is both a creative and a disciplined process. Design requires leaps of the imagination, intuitive insight, the synthesis of different ideas, and empathy with people who come in contact with any new product, system or process that is designed. Yet it also demands careful attention to detail, knowledge of scientific principles, the ability to model complex systems, judgment, a good understanding of how things can be made, and the ability to work under severe time constraints and with incomplete information and limited resources.

For engineers, design is an interdisciplinary undertaking. The variety of disciplines involved extend beyond branches of engineering and can include people with backgrounds in the liberal arts and humanities, as well as other technical disciplines from the biological and the physical sciences.

Design is learned by doing and reflecting. It is not formulaic; it is an art rather than a science.

In the literature the term design is used to describe both the act of designing and the resulting artifact (product, system, or service) or the information that fully describes it. To avoid possible confusion, in this handbook we use design to describe the action (as a verb), not the outcome (as a noun) (Ullman, 2009).

WAYS TO THINK AND TALK ABOUT ENGINEERING DESIGN

There is no universally agreed upon way to describe the engineering design process. Textbooks on engineering design typically include some form of model that sets out the process as a series of steps or stages with feedback loops and iteration (Dym & Little, 2004). Some of these models attempt to describe the various stages in a general sense, while others are more prescriptive and give considerable detail about the various activities to be undertaken and in what order (Cross, 2008).

Descriptive and Prescriptive Models of Engineering Design

Both descriptive and prescriptive models of engineering design embody a sense of flow or progression, typically shown as a series of steps or stages from top to bottom of the diagram depicting the model. They usually begin with a process of need finding and/or problem analysis and clarification, move to the generation of concepts and then the selection of a preferred concept, followed by the fleshing out or embodiment of this preferred concept into a preliminary solution which in turn is developed into a detailed solution. At each sequential stage, more is known about the artifact being designed; it is much more defined, meaning we have more information about it. This movement or progression through the stages is accomplished by feedback and iteration, as new information causes earlier information to be updated with consequential development of the ideas and information defining the artifact.

Figure 1.1 depicts a typical descriptive model of the engineering design process (French, 1971). The circles represent the information known before and after every stage. This may be in a wide variety of formats: text, drawings, sketches, photographs, moving images, physical models, prototypes or mock-ups, physical artifacts, or computer models and/or simulations. The rectangles represent actions or process steps, each of which have information as inputs and in turn result in new information, often in quite different formats. The lines and arrows indicate the flow of information including feedback to previous process steps, indicating the iterative or recursive nature of design.

FIGURE 1.1 Descriptive model of design. (Modified from French, 1971.)

Descriptive models present a general overview of a design process without going into many details. The purpose is to give a sense of the major milestones or stages. This type of model is used in most engineering design textbooks in the North America, the United Kingdom, Australia, and other countries whose education is in the Anglo-Saxon tradition. In contrast, the tradition in part of Europe is to teach prescriptive design methodologies. While this tradition goes back nearly a century it is only in the past 20 years that prescriptive models have become widely discussed in the English-speaking world.

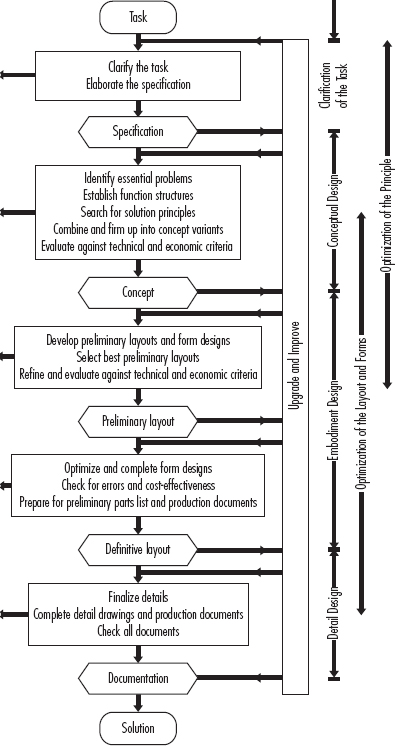

Emblematic of this prescriptive approach is the classic text by Pahl and Beitz (1996). As illustrated in Figure 1.2, the broad stages of design—for example, clarify the task or conceptual design—are indicated on the right-hand side of the model. Each stage is broken down into a set of discrete tasks as listed in the rectangular boxes. Each stage takes in information from the preceding one, creates additional information, and in turn provides this to the subsequent stage. These sets of information are shown in the boxes with the pointed ends. The iteration is indicated by the upgrade and improve band and the horizontal arrowed lines. Information flows are explicitly indicated by the dotted line on the left-hand side of the diagram.

FIGURE 1.2Prescriptive model of design. (Modified from Pahl & Beitz, 1996.)

While this model looks superficially similar to a descriptive model, there is much more detail, including the step-by-step list of design tasks. Moreover, this diagram is only a high-level summary. Pahl and Beitz (1996) and similar textbooks devote whole chapters to each stage and go into considerable detail in setting out how each task should be carried out and the sorts of design techniques that are most appropriate to accomplish each task. For instance, the conceptual design phase has five steps in this high-level model: (1) identify essential problems; (2) establish function structures; (3) search for solution principles; (4) combine and firm up the concept variants; and (5) evaluate against technical and economic criteria. However, in the detailed model of conceptual design, each of these expands to several sub-tasks. Further, the level of detail and specificity around topics like conceptual design, solution principles, and the principles of embodiment design is much higher than that found in a traditional engineering design textbook used in North America, where there is much more emphasis on component design (machine elements in mechanical design). That said, there has been a trend in recent years to incorporate more system-level and systematic design ideas in many engineering design textbooks.

Design as a Learning Activity

An alternative way to think about the engineering design process is as a learning activity. Learning is effectively a change in our state of knowledge or understanding. As previously mentioned, design is inherently an iterative process during which information is consumed and new information and knowledge about the task and/or the prospective product, system, or service being designed is acquired by the design team. As they progress through a project, design team members continuously learn more and more. In its most fundamental form this comes down to the team’s having ideas which are tested or validated by an appropriate means. Often testing of their ideas produces outcomes that were not as originally anticipated. As the team interprets and reflects upon the results of these tests, such dissonance causes them to learn something new about the project. This is illustrated in Figure 1.3.

FIGURE 1.3Idea-test-learn model of design.

This idea-test cycle is repeated at every stage of a design project from clarifying the task all the way through to documenting and communicating the final, complete description of the product, system, or service created. At each of these project stages the sources of ideas and the means of arriving at them may vary greatly. Figure 1.3 indicates only a few of the possible idea generation strategies.

Having neat ideas is not sufficient; they must be put to the test to see if they perform as imagined. This requires the team to act on the ideas in a way that will subject the ideas to scrutiny in a way that will assess their veracity. As with idea generation, testing takes place in varying degrees throughout the design project. This can be something as simple as a thought experiment or a simple prototype made from bits and pieces at hand all the way up to, say, the flight-testing of a new concept of aircraft. Types of testing can include modeling and analysis, simulations, physical mock-ups, working prototypes of subsystems or assemblies, or early prototypes. The design thinking movement espouses that the prototyping of ideas be done early and often (Brown, 2009). This accelerates the learning process by going through a large number of idea-test-learn cycles in a short period of time.

Similarly, it is not sufficient to merely test an idea or a system; the findings have to be reflected upon critically so as to extract the deep and lasting lessons to be learned. This is not as easy as it sounds. It takes a disciplined approach and an inquiring, sometimes skeptical mind. The learnings need be captured, kept, communicated, and acted upon as appropriate throughout the remainder of the project. Some of this knowledge may be vital across the whole life cycle of the artifact being designed.

Design as Critical Thinking

Engineering design is not an exact science that has single, absolute, immutable answers. Rather it is a situated and contingent activity. Engineers have to develop the confidence and the courage to make professional judgments on the basis of evidence and argument. They have to be able to make tough calls that can literally have life and death consequences and be prepared to live with those consequences. This requires critical thinking of the first order.

Even if a prescribed methodology is adopted, the design process requires engineers to make simplifying assumptions so that the creative work can proceed. They must step from the physical world, where the laws of nature apply, to the model world, where it is not possible to simulate every aspect of the behavior of even an ideal system. Subsequently, engineers make critical decisions on the basis of these assumptions and incomplete information. The availability of design information is limited by many factors, including available time, finite human resources, gaps in knowledge (especially in cutting edge projects), ready access to timely and up-to-date information, and the ability to adequately communicate what is known. This cycle is depicted in Figure 1.4.

FIGURE 1.4Design assumptions and decisions.

Design as critical thinking depends upon the team’s ability to model the prospective performance of proposed concepts and systems using prototyping and simulation. While the level of sophistication and completeness and hence veracity of such modeling and simulation continues to improve, models are only ever an approximation to reality. This is due to a combination of our ability to fully describe how complex technical, let alone sociotechnical, systems behave and the uncertainty in the values of the properties of the components. Professional judgment is required to both create models and to interpret their outputs. So while many of the tools and techniques that engineers use when designing are powerful and precise and rely on scientific knowledge, the overall design process does not have these characteristics. The engineering design process does not have the predictive certainty of science.

Design as Lived Experience

Engineering design is a social activity (Brereton, Cannon, Mabogunje, & Liefer, 1997)—a deeply human activity (Petroski, 1982). While it may be concerned with technological artifacts and knowledge, it is carried out by people, typically from diverse disciplines, working in teams. A number of researchers have studied the human act of designing in fields including engineering (Bucciarelli, 1996) and architecture (Cuff, 1992), complete with the frailties and ambiguity inherent in language and human discourse.

A recent study of designers (Daly, Adams, & Bodner, 2012) working in diverse fields from engineering to instructional design and fashion design used phenomenography to discover the variety of ways in which designers experience design. The findings are summarized in Table 1.1. The respondents experienced design in one of six broad ways, each characterized by a word or phrase (e.g., evidence-based decision making). The researchers describe each of these six different ways of experiencing design in terms of a short description expressed as design is …. From the top to the bottom of Table 1.1, there is a progression in the way that design is experienced: from a bounded, procedural experience toward a more unbounded, emergent, learning, and meaning-making experience.

TABLE 1.1 The Variety of Ways That Design Is Experienced

| Design was esperienced as … | Design is … |

| Evidence-based decision making | Finding and creating alternatives, then choosing among them through evidence-based decisions that lead to determining the best solution for a specific problem. |

| Organized translation | Organized translation from an idea to a plan, product, or process that works in a given situation. |

| Personal synthesis | Personal synthesis of aspects of previous experiences, similar tasks, technical knowledge, and/or others’ contributions to achieve a goal. |

| Intentional progression | Dynamic intentional progression toward something that can be developed and built upon in the future within a context larger than the immediate task. |

| Directed creative exploration | Directed creative exploration to develop an outcome with value for others, guided and adapted by discoveries made during exploration. |

| Freedom | Freedom to create any of an endless number of possible outcomes that have never existed with meaning for others and/or oneself within flexible and fluid boundaries. |

Modified from Daly, Yilmaz, Christian, Seifert, & Gonzalez, 2012.

This study suggests that design can be experienced as a relatively defined process of the type depicted in descriptive and prescriptive models of the design (i.e., evidence-based decision making or organized translation). Equally it can be experienced as a much more personal and nuanced progression of discovery (i.e., personal synthesis and intentional progression). This is not captured in typical models of design. The final two types of experience are values based and much more about finding creative expression, or empowerment, in a large solution space (i.e., directed creative exploration and freedom). These different ways of experiencing design impact the types of information sought and generated during a project and often the ways in which this information is captured and communicated.

SUCCESS FACTORS IN ENGINEERING DESIGN PROJECTS

Engineers design in teams in the context of a project. The Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) (Project Management Institute, 2000, p. 4) defines a project as “a temporary endeavour undertaken to create a unique product or service” or as “an endeavour in which human, (or machines), material, and financial resources are organised in a novel way, to undertake a unique scope of work, of a given specification, within constraints of cost and time so as to deliver beneficial change defined by quantitative and qualitative objectives.” The implications of this are that the information needed for a given design project might have to be assembled specifically for the unique circumstances of that project or perhaps repurposed and reconfigured from resources used on similar but different past projects.

Why Engineering (Design) Projects Succeed or Fail

While all engineering projects aim to be successful, the irony is that design failures provide valuable lessons that can underpin future success (Petroski, 1982). Failure of an engineering project, including design projects, can be technical, economic, environmental, or sociocultural. Box 1.1 contains a list of seven frequently occurring reasons for project failure (Eisner, 1997). The first six all depend to a greater or lesser degree on some aspect of how information is discovered, accessed, interpreted, communicated, used, modified, created, captured, curated, and managed.

BOX 1.1

Why Engineering Projects Fail

1.Inadequate articulation of requirements

2.Poor planning

3.Inadequate technical skills and continuity

4.Lack of teamwork

5.Poor communication and coordination

6.Insufficient monitoring of progress

7.Inferior corporate support

Data from Eisner, 1997.

Based on the analysis of many engineering design projects that resulted in artifacts that failed, Hales and Gooch (2004) identified ten strategies (see Box 1.2) that can help engineering designers avoid failures. Attending adequately to any of these implies a sophisticated level of information literacy, in the broadest sense, including an appreciation of the cultural or linguistic assumptions behind information and how it is represented, especially when working in a global context. These success strategies assume the members of the design team appreciate the social and cultural mores and the aesthetic sensibilities of diverse user communities. Existing artifacts and depictions of their use are therefore a vital source of information for designers as these objects embed critical social and cultural knowledge. Without this information it is difficult to identify the real problem and a complete set of requirements, communicate effectively, make the functions clear, select appropriate materials, and so forth.

BOX 1.2

Strategies for Design Success

1.Define the real problem or need

2.Work as a team

3.Use the right tools

4.Communicate effectively

5.Get the concept right

6.Keep it simple

7.Make functions clear

8.Make safety inherent

9.Select appropriate materials and parts

10.Ensure that the details are correct

Data from Hales & Gooch, 2004.

Managing Expectations

Success in design is ultimately about managing expectations. There must be convergence between the perceived needs and the emergent solution, as experienced by multiple stakeholders with differing perspectives. The real need is never fully known at the outset, and perceptions of the need can change over time. Success involves arriving at a mutually agreeable destination rather than being on a predictable journey from A to a B, where B is defined precisely at the outset. This does not imply that design is a random exploration without a target. The idea of managing, as much as meeting, expectations recognizes the contingent nature of design and the reality that the target will change during the course of any nontrivial project as new information emerges or is discovered.

The PMBOK (Project Management Institute, 2000) defines project management as the application of knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques to project activities in order to meet or exceed stakeholders’ needs and expectations from a project. Meeting the needs of the stakeholders implies that the design team knows who all the stakeholders are in a given project, not simply the client who approaches the designer initially with a brief or a request for proposals, but all those individuals and groups who will come in contact with the product, system, or service being designed throughout its life cycle—from inception to decommissioning and recycling or reusing the artifact or its elements after its operational life. Thus a designer needs to identify all the potential stakeholders and know enough about them so as to be able to determine their possible needs and expectations. These needs not only are technical in nature but also could draw on cultural, historical, social, geographical, economic, and other nontechnical types of knowledge.

Information literacy is a critical skill in resolving the following set of questions related to managing expectations. What is the scope of the project (what aspects are to be included)? What has been done previously to tackle this need? Are there analogous circumstances we can learn from? What are the roles and responsibilities of the team members? What has to be communicated to whom, and when and how should communication take place, to capture and preserve vital information? How can we create sharable models and other representations of the emergent artifact that are readily accessible for different participating disciplines and stakeholders? What information is there that can help the team to develop into an effective group that sustains high levels of performance?

Dealing with Uncertainty

Design projects of any substance are complex in the sense that they exhibit emergent properties. At the commencement of any project it is impossible to have complete knowledge of everything that might happen nor every piece of information that might be needed. During a design project it is not possible to predict completely nor with perfect precision how the product, system, or process being designed or its component parts or assemblies will behave under all possible circumstances. Accordingly, engineers must be comfortable with ambiguity and be able to handle uncertainty. These related abilities are bound up in the concept of risk and risk management. The PMBOK defines risk management as the “processes concerned with identifying, analyzing, and responding to risk [throughout the project life cycle]. It includes maximizing the results of positive events and minimizing the consequences of adverse events” (Project Management Institute, 2000, p. 127). Risk is a combination of the frequency (or probability) of occurrence and the consequences of a specified (hazardous) event.

Examples of the types of risks that frequently impede the success of engineering design projects listed in Box 1.3.

BOX 1.3

Engineering Design Risks

1.Insufficient or inappropriate personnel or project plan

2.Requirements not adequately identified or defined

3.Noncompliance of system to requirements

4.Program scope increases due to requirements creep

5.Using unproven technology

6.Poor knowledge management or poor quality systems

7.Delays in procurement of materials or parts

8.Materials do not meet the specification

9.Insufficient infrastructure for integration schedule

10.Technical performance not supportable in field

11.Reliability inadequate or issues with logistics

12.System not maintainable to end of program or life cycle

Each of these risks has a critical information dimension. Reducing the uncertainty and hence managing these risks is highly dependent upon having the most complete and accurate information available at the time it is really needed, tracking key information and its interdependence upon design decisions, being able to locate the right information quickly and easily when required, keeping information up to date, and preserving the integrity of information over the life cycle of a product, system, or service.

Grasping Opportunities

The counterpoint to risk is opportunity. From uncertainty there may arise opportunities to do things a different way or to take the project in a different, more fruitful direction. Grasping the upside of uncertainty can be just as important to the success of a design project as managing the potential downside of risks. Indeed, many national and international standards on risk management actually cover both risk and opportunity management. Unfortunately, the overwhelming bulk of the material in such standards focuses on risk, which is a reflection of the designer’s imperative to avoid being responsible for a foreseeable fault or problem in a project outcome.

Strategies for making the most of potential opportunities in design include the following: using modern value engineering or value management techniques to continuously seek better ways to do things; negotiating changes to the project scope to enable alternative solutions to apply (e.g., solutions that that reduce the life cycle cost, better meet requirements, or meet implicit client/stakeholder needs); freeing up project constraints to enable alternative approaches/solutions; and broadening the search of solutions to similar problems to reveal new technologies or approaches that open up out-of-sector solutions.

Measures of Success

A simple way to consider the success of a design project is to use the three generic criteria espoused by the internationally renowned new product development firm IDEO (Brown, 2009): user desirability, technical feasibility, and business viability. A successful product, system, or service must meet the actual needs of the prime user and more generally consider all of the people who will encounter it during its life cycle—from conception to recycling. That is, the approach to design should be human centered (Donald, 1988). Second, products, systems, or services can only be successful if the underlying technologies are sufficiently capable and robust enough to ensure safe, reliable operation. Innovative design concepts can be ahead of their time in the sense that the most appropriate technology does not yet exist to enable the idea to be effectively realized. Finally, a product, system, or service must also be viable in terms of its whole of life cost—not just the purchase price in relation to the production cost. Further, there must be a viable business model in place. Business success can be measured in pure dollar terms or other ways as appropriate. To be successful, the design solution must deliver sustainable value when viewed from all three of these perspectives, not just one or two of them.

Safety, Clarity, and Simplicity

One design strategy that can help to achieve this sustained value is to ensure that the chosen concept and the way it is embodied meets the following three basic criteria: safety, clarity, and simplicity (Pahl & Beitz, 1996).

Safety. The concept and its form should be inherently safe. It should not be necessary to design in safety features as an afterthought during detailed design in order to overcome problems that could have been avoided in the earlier stages of the project.

Clarity. The operation of the product, system, or service should be obvious to the users and clear for them to easily understand, even intuitive. Clarity in the form and function is also critical for people other than users (e.g., maintenance personnel) who must work with the product, system, or service at any point during its life cycle.

Simplicity. In essence, keeping things simple often results in artifacts that are easier and less expensive to manufacture, as well as easier to maintain. This is also known as the KISS principle: Keep it Simple for Success. Apple products are an excellent contemporary example of simplicity deployed as the guiding design philosophy (Segall, 2012).

Engineers have been known to design things that are unnecessarily complicated or have too many bells and whistles when a much more straightforward solution would have sufficed (Thomke & Reinersten, 2012). Mark Twain is reputed to have apologized for sending his friend a long letter as he did not have time to write a shorter one. Similarly, it is much more difficult to create a product, system, or service that is inherently safe, clear to understand, and simple to make or use than it is to create an overly engineered artifact.

The last word in design success comes from physicist and Nobel laureate Richard Feynman. In a famous minority appendix in the Rogers Commission Report on the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger, Feynman (1986) made an important and sobering distinction between reliance upon authentic information rather than mere rhetoric in making critical design or operational decisions: “For a successful technology, reality must take precedence over public relations, for nature cannot be fooled” (“Conclusions,” para. 5).

IMPLICATIONS FOR STUDENT DESIGN PROJECTS

In learning to design, engineering students expect some guidance on what to do, when to do it, how best to do it, and so forth. It is clear that while engineering design is often represented as a multistage process with iterations, the reality and the experience of a real design project is much more human, contingent, and complex. While the teaching of specific design techniques (e.g., brainstorming) and analysis tools (e.g., computer simulation) might be amenable to instructional techniques, the overall process of conducting a design project is much more elusive and therefore almost impossible to teach. Those from the European tradition of design education constructed around prescriptive design models would argue that the overall process of engineering design can be taught.

Many experienced design educators have found that teaching design is more about coaching individuals and student teams through a series of scaffolded learning experiences preferably based on authentic design tasks. This is easiest to achieve if there are regular design experiences spread periodically across the curriculum (e.g., one every semester) and if these are centered on increasingly challenging tasks—challenging either in the scope or in the scale of the project. This approach also affords the opportunity to develop and integrate a breadth and depth of corresponding information literacy skills over a multiyear period. Of course, this professional growth and development continues beyond the completion of college and spans a career.

The methods and tools available in engineering practice and how and when these are used are not the same as those for a typical student engineering design team. Most students would be classified as novice designers with limited experience. Furthermore, the range and diversity of design and other professional experience in a student team is narrow, even if the students are enrolled in quite different majors. For university-based projects, typically there is little in the way of “corporate memory,” such as comprehensive documentation of past projects, lists of lessons learned, or even cogent advice on the best ways for approaching and managing projects. While some design researchers have developed and assessed the use of electronic repositories and knowledge exchanges with student design teams, this is the exception rather than the norm. In contrast, teams in industry have access to very sophisticated company- or even industry-wide Web-based collaboration tools that enable sub-teams of specialists from around the globe to participate and which have vast stores of product information data and test data. These differences between the working environment of student design teams as compared with that of engineering practitioners poses some interesting challenges and indeed opportunities for how we develop effective information literacy interventions in engineering schools and associated technologies to foster and support good information practices that carry beyond the classroom.

SUMMARY

There are many approaches to experiencing engineering design, including process-oriented, human-oriented, and learning-oriented. However, whichever way engineering design is taught, it is intrinsically a complex activity and, while structured, is ultimately creative as well. It thus requires the integration of many information inputs, synthesis, and analysis, which results in the construction of something that has not existed before. In order to ensure the best chance of success in completing a project to the expectations of the clients, information needs to be gathered, organized, and applied appropriately, ethically, and efficiently. Like other professional skills, information management skills need to be addressed in the engineering curriculum to ensure that students can create rich solutions to the design challenges they will face in their professional careers.

REFERENCES

Brereton, M. F., Cannon, D. M., Mabogunje, A., & Liefer, L. J. (1997). Collaboration in design teams: Mediating design progress through social interaction. In K. Dorst (Ed.), Analyzing design activity. New York: Wiley.

Brown, T. (2009). Change by design: How design thinking transforms organizations and inspires innovation. New York: HarperCollins.

Bucciarelli, L. L. (1996). Designing engineers. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Cross, N. (2008). Engineering design methods (4th ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Cuff, D. (1992). Architecture: The story of practice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Daly, S. R., Adams, R. S., & Bodner, G. M. (2012). What does it mean to design? A qualitative investigation of design professionals’ experiences. Journal of Engineering Education, 101(2), 187–219. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2012.tb00048.x

Daly, S. R., Yilmaz, S., Christian, J. L., Seifert, C. M., & Gonzalez, R. (2012). Design heuristics in engineering concept generation. Journal of Engineering Education, 101(4), 601–629. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2012.tb00048.x

Donald, N. (1988). The design of everyday things. New York: Basic Books.

Dym, C. L., & Little, P. (2004). Engineering design: A project-based introduction (2nd ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Eisner, H. (1997). Essentials of project and systems engineering management. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Feynman R. P. (1986). Report of the Presidential Commission on the Space Shuttle Challenger Accident: Appendix F—Personal observations on the reliability of the shuttle. Retrieved from http://science.ksc.nasa.gov/shuttle/missions/51-l/docs/rogers-commission/Appendix-F.txt

French, M. J. (1971). Engineering design: The conceptual stage. London: Heinemann Educational Press.

Hales, C., & Gooch, S. D. (2004). Managing engineering design (2nd ed.). London: Springer-Verlag. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-0-85729-394-7

Holt, J. E., Radcliffe, D. F., & Schoorl, D. (1985). Design or problem solving—A critical choice for the engineering profession, Design Studies, 6(2), 107–110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0142-694X(85)90020-1

Pahl, G., & Beitz, W. (1996). Engineering design: A systematic approach (K. Wallace, L. Blessing, & F. Bauert, Trans., 2nd ed.). K. Wallace (Ed.). London: Springer-Verlag.

Petroski, H. (1982). To engineer is human: The role of failure in successful design. New York: Wiley.

Project Management Institute. (2000). A guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge—PMBOK® Guide: 2000 Edition. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

Segall, K. (2012). Insanely simple: The obsession that drives Apple’s success. New York: Portfolio Hardcover.

Thomke, S., & Reinertsen, D. (2012). Six myths of product development, Harvard Business Review, 90(5), 84–94.

Ullman, D. G. (2009). The mechanical design process (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.