The most important human endeavour is the striving for morality in our actions. Our inner balance and even our very existence depend on it. Only morality in our actions can give beauty and dignity to life.

Albert Einstein

During his lifetime, Alexander admired the way that acrobatic performers used themselves while both keeping still and moving. He noticed that these performers, whether on or off the stage, moved with the maximum efficiency and gracefulness.

Acrobats have learnt to be in harmony with gravity, as they need to be perfectly balanced in all the actions that they perform, and as a consequence have an elegance and poise similar to that of young children. Acrobats use gravity to help them in many of their awe-inspiring acts. This is also true for the surfer, skater and dancer, because balance and fine coordination are of the essence. While the acrobat lives life in balance and working with gravity, many of us, in contrast, are constantly fighting gravity with excessive muscle tension in our every waking moment. This tension becomes so habitually ingrained over the years that we even tense our muscles while asleep, evidenced by the common problem of grinding teeth at night. In fact, poor posture has become so common that it is now perceived as normal, so much so that it has become striking when we see a person with an upright and balanced posture.

Since the mind, emotions and body are, in essence, all the same thing, when we are in balance so too are our emotions (which we experience as calmness) and our minds (which we experience as metal composure). So moving in balance can produce calmness on other levels too. Our posture is really the sum of thousands of thoughts we make each and every day, and by changing these thoughts, while walking, sitting and bending, we can see and feel a profound effect on our overall wellbeing. The American Trappist monk Thomas Merton once said: ‘Happiness is not a matter of intensity, but of balance, order, rhythm and harmony.’ By bringing balance, order, rhythm and harmony into our everyday movements, we will not only be improving our posture but we will be bringing our whole life back into balance.

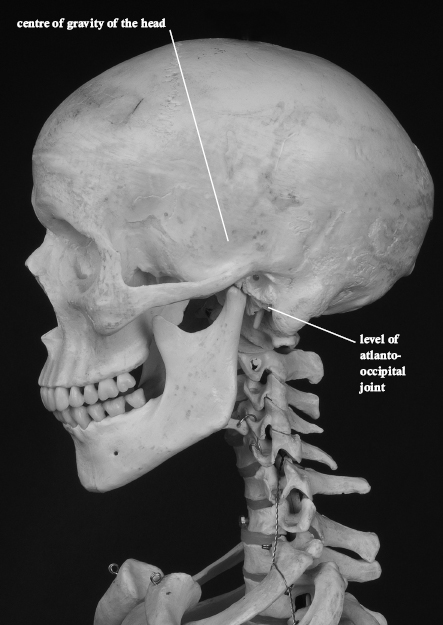

37: Good posture is synonymous with good balance. When improving the way you use yourself, it can be helpful to be aware of how your head is balanced on top of your spine.

The human body is, in fact, an amazing anti-gravity mechanism, which is delicately balanced by a series of intricate reflexes and internal feedback mechanisms that continuously inform the brain. This, in turn, organizes our movement in perfect balance, without any conscious effort on our part. If we begin to lose balance, the right mechanisms immediately come into play to restore our equilibrium. The habit of over-tensing muscles severely interferes with this natural organization.

Let us consider the human body for a moment: it is one of, if not the most, unstable structures living on the planet. We consist of over 650 muscles and 206 bones, all of irregular shapes, constantly balanced one on top of another. Right at the bottom we have arched feet, which support the lower legs, which in turn support the upper legs, and on top of the legs balances the pelvis. These structures are made up of joints and incredible mechanisms comprising a rounded bone balancing on another rounded bone, (which can be clearly seen in the case of the ankle, knee and hip joints. Further up the body we have the spine, balancing on the pelvis, which itself comprises 24 vertebrae, which are placed one on top of the other. And if that is not the most amazing balancing act you have ever seen, right on top of the spine sits the head, which is finely balanced and on average weighs about 4.5 kg (10 lb). It does not take much to see that not only is the human body inherently unstable, but also that we are very, very top-heavy, and therefore we require little or no effort to move, but conversely we require a lot of effort to maintain a position or fixed posture. So in reality we are all acrobats, and even standing consists of several balancing acts at any given time; this is, in fact, one of nature’s most amazing miracles. So if we are ever to have good posture we need to develop a good sense of balance! Einstein once said ‘To keep your balance you must keep moving’ and good posture is all about movement and not about position.

Not only does the weight of the head cause us to be ‘top-heavy’, it is actually set off-balance on top of our spines. It is set in such a way that if we relax the neck muscles, the head is inclined to drop forwards. If you watch someone falling asleep while sitting in a chair, you’ll notice that the head invariably drops forward and down onto the chest. So not only are we trying to balance the relatively heavy weight of the head on the spine, but we are also coping with the fact that its point of balance is not under its centre of gravity (See photo 38).

38: The centre of gravity of the head is situated forward of the balancing point (atlanto-occipital joint). This means that we are designed to move by releasing tension rather than increasing tension. By learning the Alexander Technique many people say they feel their movements are lighter as they realize that they hardly need any effort to perform everyday tasks.

At first this might sound confusing, until you realize that the reason that the pivot point of the head is behind its centre of gravity is to make movement effortless. All we have to do to move is to release the muscles surrounding the neck joint (the atlanto-occipital joint) by allowing the neck to be free. The head will then go slightly forward on the spine in an upward direction, and this slight forward adjustment of the head will take the rest of the body into movement, as long as there is freedom in all the other ‘hinge’ joints (ankles, knees and hip joints). In other words, in order to move, a human being has only to let go of the tension in certain muscles and a complex reflex system will do the rest. Most other movements require effort, and the maximum effort is needed at the beginning of the action. For example, a car or aeroplane needs most power when it accelerates from a stationary position; it needs much less energy to keep it going at a constant speed. The human body, on the other hand, needs no effort to move and actually requires a release of muscle tension. Once the head begins to move forwards, the body will naturally follow, and the reflexes then spring into operation as a response to the movement. In short, the relative position of the head in relation to the neck and back controls, organizes and guides all our movements for us with little or no effort on our part. When the head is not balanced, the Primary Control, as Alexander called it, ceases to work effectively or efficiently. You will need an Alexander teacher to show you this as it is difficult to experience this on your own.

“I love the Alexander Technique. It has corrected my posture, improved my health and changed my life.”

Alec McCowen CBE, actor

To maintain this balance it is important to be aware of how you use your eyes. It is a common habit for people to look down by letting the whole head and neck drop, rather than looking down just with the eyes and keeping the head lightly balanced on top. You become aware right now as you are reading this book: are you looking down with your eyes or the whole head? In my own teaching I have also found that many people can dramatically alter the balance of the head when wearing varifocal or bi-focal glasses, and tend to pull their head back when reading so that they can look through the part of the lens that is suitable; without knowing it, they are probably giving themselves chronic neck problems. If you are one of these people, the Technique can help you to become aware of the habit and learn to read in different way.

39: When using varifocal or bi-focal glasses, many people unconsciously get into the habit of pulling their head back onto their spine when reading. This can often become a habit and consequently lead to neck problems and tension headaches.

It is important to recognize that standing is an activity rather than a position. If you watch a young child standing, you will see that they are not actually still, but swaying very gently in balance. They are not doing so consciously: their reflexes are. Adults, on the other hand, often stand in fixed positions, but the effect of deliberately ‘standing up straight’ and ‘pulling our shoulders back’ is to pull us off balance and is therefore detrimental to good posture. As we saw in the last chapter, standing in a straight position might also not be as easy as we think, as we cannot feel with our internal senses what is straight and what is not. The only real way to tell when we are balanced and when we are not is by means of the weight distribution in the feet. If we are unbalanced, the weight will be thrown onto the front, back, insides or outsides of our feet, and just by noticing where this distribution of weight is, we can become much more aware of how we are standing, even when we do not have a mirror to directly inform us of the reality. When standing, the weight distribution should be on three points of each foot, and this brings a certain amount of balance. The first point is the heel, the second is the ball of the foot and the third is situated on the outside of the foot at the beginning of the little toe. If you are habitually standing on only two or even one of these three points, you will be less balanced, and consequently you will need to tense many more muscles to keep you upright.

Remove your shoes and stand up as you usually do while you are reading these words. Ask yourself whether you are standing more on one foot than the other, or are you equally balanced on both of your feet? Even if you find you are equally balanced on both your feet, ask yourself if this is your usual way of standing, and, if not, stand in a way that feels normal to you and then ask yourself the same questions again.

Now see if you are standing more on your heels or more on the balls of your feet, as this will help to indicate whether you are leaning backwards or forwards. Similarly, see if you are standing more on the outside or on the inside of your feet, and remember that this can be different for each foot. The habit of standing more on the inside of your feet can produce ‘flat feet’, which is the outward sign of the habit of pulling your body down and the knees towards each other. Lastly, ask yourself if your knees are locked back with excessive tension, or if they are over-relaxed so that your knees are bent?

By asking these questions, you can begin to notice your own habitual way of standing and decide whether it is balanced or unbalanced. We can improve our standing by being conscious of the way we stand and by making sure our feet are making even contact with the ground. It can also be a good idea to observe the way other people stand in shops and banks when waiting in a queue, as this can increase your general awareness.

There is no one right or correct way of standing, and, in fact, there are many ways of standing that do not put undue pressure on the body. An important characteristic of a beneficial way of standing is that it is balanced. Alexander did not advocate any one correct way of standing, as he maintained that this would only encourage a new set of habits, but he did give his pupils useful suggestions to remember while standing:

1. Place the feet approximately 30cm (12in) apart, as this immediately gives a more stable base on which to support the rest of the body. Note: this measurement is from the inside of the feet; so for tall people the feet need to be a little further apart and for short people a little closer together.

2. When standing for long periods, it is helpful to take one foot approximately 15cm (6in) back, so that about 60 per cent of the weight of the body is resting on the rear foot. Place the feet with an angle of approximately 45 degrees between them. This helps to prevent the all-too-common habit of sinking down into one hip, which can affect the balance and coordination of the whole structure of your body.

3. If you notice that you are pushing your pelvis forward, imagine it gently releasing back without deliberately throwing the body too far forward (make sure you are allowing your neck to be free and your head to move forward and up and your spine to lengthen at the same time). This helps to eliminate the very common tendency of over-arching the back when in a standing position. Note: make sure you are only thinking and not actually doing this action.

40: The unbalanced way in which we stand may also cause excessive tension throughout the body, leading to a variety of back, neck, hip, knee and foot problems.

41: By placing your feet a little way apart, with one slightly behind the other, as shown, you can stand in a much more balanced way. This in turn can dramatically reduce tension and can alleviate an array of muscular or skeletal problems.

Compared to our grandparents, we spend many more hours a day sitting in chairs. It is a good idea to separate sitting into two distinct categories: sitting for relaxation and sitting in activity. While you are sitting for relaxation, for example, when using a reclining chair or a sofa or armchair while watching TV, you only need to let the chair fully support you, so that no one part of your body has to bear undue pressure or tension. You can always use cushions to support your head if you need to.

Sitting while in activity is a different matter altogether, and sitting at a desk or table while working or eating requires us to be balanced on the two sitting bones and feet. Make sure that you have even support on all these four areas, and when you are leaning forward at a desk or table, do not bend your spine, but rather use your hip joints and sitting bones to help you to transfer weight from the sitting bones onto the feet. When moving back away from the desk, just reverse the process and transfer your weight back over your sitting bones. While you are sitting during any activity, try to be balanced, poised and movable rather than hold any one fixed position. Last but not least, make sure your chair is well designed. (See also chapter 8 on posture and furniture.)

Bending down is yet another amazing balancing act! When bending down to pick objects up, many people do not bend their knees sufficiently – and sometimes not at all. Often you will see people actually bending at the waist, where in fact there is no hinge joint, so in reality they are bending their spine. This can cause not only direct damage to the spine, but also the body to be completely out of balance, immediately putting enormous strain on the entire muscular system, especially the back, thigh and neck muscles, which have to tighten to prevent the person falling over. The crucial point here is that, without realizing it, they are actually lifting more than half their body weight every time they straighten up from bending to pick up even a light object, which causes even further muscular tension. This sort of misuse is a disaster for the body, and, if habitual, can often directly cause lower back pain and neck problems. Furthermore, all the internal organs are put under pressure and breathing is restricted. If you ever watch young children, indigenous people or professional weightlifters, you will see that they squat when bending, using their very powerful leg muscles. You will rarely see young children or indigenous people bending down without bending their hips, knees and ankles. Some time ago I heard an interesting story about some missionaries who went to Africa and mixed with some native people. The native people were awestruck by the fact that the white missionaries often bent down from the waist without bending their knees, and so they gave them an African name, which, when directly translated, meant ‘the tribe without knees’! All joints require natural and regular movement to keep them healthy, so by using your major joints in order to maintain balance and equilibrium, you will also be keeping your joints free from problems and your muscles perfectly toned.

42: The full effects of the misuse of ourselves can easily be seen in this X-ray image of a person working at a computer. This person, like many others, is completely unaware of the damage he is doing to himself.

43: By learning the Alexander Technique, we can regain our natural poise and balance while performing simple everyday tasks such as working at our desks, and so avoid a multitude of health problems in later life.

44: Many people in developed countries bend their backs instead of the knee, hip and ankle joints when picking up objects. This is not how nature designed us to work and this way of moving can lead to a wide range of muscular or skeletal problems, such as back pain, later in life.

45: By the use of inhibition and direction, we can learn to choose a different way of moving, which puts less strain on ourselves.

Try picking a magazine off a coffee table in your usual way and stop just as your hand reaches it. Ask yourself the following questions: Are your knees bending? If so, by how much? Do you feel in balance or unbalanced? Can you feel any tension in your body, and, if so, where? How much overall effort are you using in this simple activity?

Now repeat the same action, only this time make a conscious decision to make sure you allow freedom in your neck so that your head can move forward and up and your spine can lengthen. At the same time, allow your knees to bend so that they go forward and away from each other. Allow them to bend more than you normally would, but make sure that you are not pulling them in towards one another. Does this feel more balanced and easier on your muscles and joints? You will help yourself to improve overall posture overnight if you start to use the hip, knee and ankle joints as nature intended in order to keep you balanced in the hundreds of actions you perform every day. Remember, new ways of moving will feel strange at first.

Many of us make a big deal about getting out of a chair. This is because we have an idea that we are trying to leave the chair in a vertical fashion, and by doing this we think of ourselves as having to fight gravity, putting enormous strain on our entire structure. But getting out of a chair is simply transferring your weight from the chair onto the feet and can feel effortless if we use the body’s natural mechanisms and reflexes. After you have had a few Alexander lessons, you might like to try this following procedure: first, try getting up slowly in your usual way and see if you can feel the stresses and strains in your legs, neck, back or feet. Now do it again slowly, following these simple instructions:

1. Make sure that your feet are a little apart and not too far forward. Your knee should be roughly above the front of your foot.

2. As you begin to stand up, allow your head to move first by allowing it to go slightly forward and up away from your shoulders, then allow the rest of your body to follow.

3. While moving, think of the back lengthening. Make sure your neck does not drop downwards or your head get pulled back (thinking of your head moving away from your pelvis will help).

4. Only bend forward in the area of the sitting bones or the hip joint by ‘hinging’ at the hip joint and not at waist level. (See photo 36, page 113).

5. As more weight goes onto your feet, you will feel an increased pressure under the feet, which triggers your postural reflexes, and you will begin to leave the chair spontaneously and with little effort.

6. As you leave the chair, allow most of your weight to go through the heels, thinking of your hips, knees and ankles ‘unbending’, rather than straighten the legs by over-tensing your leg muscles and pushing your feet into the floor.

If this is done in a balanced way, you should be able to pause at any moment with grace and ease and feel totally balanced.

A common habit that many of us have is to fall backwards when sitting down. This immediately unduly excites what Alexander called our fear reflexes and causes the head to retract backwards, the shoulders to hunch and the back to over-arch, because the body senses it is off balance and tries to protect itself. Again, if this is the habitual way we sit down, the body will retain this tension unconsciously, and the neck, shoulders and back can remain permanently in a state of tension. The natural way to sit down is to allow the head to move forward (without allowing the neck to drop down) and at the same time to bend the hips, knees and ankle joints so that you descend in perfect balance. Again, you should be able to pause at any moment and balance with ease. As your sitting bones reach the chair, allow them to roll back, keeping your head balanced and your back in a lengthened state. If you are really in balance, you will be able to change your mind and get up at any time you want to without making any effort. It is essential to realize that the instruction of the ‘head going forward’ is in relation to the top of the spine and not in space. It is not ‘face forward’ but the whole of the head; thinking of your nose dropping minutely can be helpful.

So by thinking about the balance of your body as a whole during your activities, you will be accessing your inner acrobat. This will naturally improve your sense of physical integrity, improving your posture, poise and grace of movement. And don’t forget that you are doing a balancing act of your head resting on top of your spine wherever you go!