Breath is the bridge which connects life to consciousness, which unites your body to your thoughts.

Thich Nhat Hanh

Breathing is arguably the most important activity we will ever perform – it is the first thing we do as we come into the world and it is the last thing we will ever do as we leave. It quietly and consistently fills our lungs and gives us life. Its serene presence is always there, ready to be accessed at any moment, yet for the most part it goes unnoticed and unappreciated because we are preoccupied with other matters. The way we breathe can affect the way we live our lives – and the other way around. If we have a feeling of being rushed during our daily activities, our breathing often becomes faster and more shallow, so that we do not take in enough air. If we have a habit of breathing in a fast and shallow way, it’s likely that we will feel that we are constantly in a hurry, never feeling we have enough time. It’s easy to set up a vicious cycle where the quality of breathing deteriorates. These detrimental effects can often be seen in later life when people’s breathing rate has become very rapid. If we are breathing naturally, on the other hand, we will feel generally more relaxed and more in control of our lives.

In natural circumstances, we take breaths without any effort on our part; we do not even have to remember to breathe, but we do need to learn how not to interfere with our primary life-enhancing mechanism. As you are reading these words, become aware of the silent inhalation and exhalation that is taking place at every moment. See if you can get a sense of the force or energy that is drawing the air into and then out of your lungs. As with many other natural functions of the body, many people unconsciously and habitually interfere with this simple act of breathing. The excessive muscular tension associated with poor posture can distort breathing, causing a lack of energy or tiredness. In extreme cases, misuse of the body can even exacerbate life-threatening breathing problems such as asthma.

To try to improve posture without reference to breathing, or to try to improve breathing without reference to posture, could be compared to talking about the act of eating without taking into account chewing. Posture and breathing are inseparable, and each one directly affects the other; the way we use ourselves, whether well or badly, will have an effect on how we breathe. It is easy to demonstrate this interrelatedness between posture and breath by sitting in a heavily slumped manner. If you try it for a moment or two (but not too long!), you can feel that you are unable to breathe deeply and freely. The same is true if you ‘sit up straight’ in a rigid way, by over-arching your back. If poor posture is a habit, then restricted breathing will also be a habit, leading to breathing problems. If we can learn to use ourselves in a more balanced way, our breathing will be less restricted, and if we learn to breathe well, it will help to reduce muscle tension so that we will be more able to sit, stand and move with poise and balance.

When Alexander began teaching the Technique, he was known as the ‘breathing man’ because he was able to help so many people improve the way they breathed. In fact, as we saw in earlier chapters, he developed the Technique to sort out his own breathing and voice problems, and he went on to use the Technique to help his fellow actors to improve theirs, through better posture, coordination and balance.

“The Alexander Technique has helped me to undo knots, unblock energy and deal with almost paralysing stage fright.”

William Hurt, actor

Over-tight muscles can affect the functioning of the ribcage, the lungs, and even the nasal passage, mouth and throat (trachea), through which air passes. They can also produce a general ‘collapsing’ or slumping of the whole torso, which can greatly restrict the lungs’ capacity to take in air, leading to shallow breathing. Shallow breathing means that we have to expend more effort in order to take in sufficient air. In short, without realizing it, we can make the effortless act of breathing very hard work. This increased physical exertion goes largely unnoticed, because over many years we have become accustomed to our shallow and often laboured breathing, so that it just feels ‘normal’ and ‘right’ to us. A doctor once remarked that the average office worker does not take in enough air to keep a cat in good condition, and from my own experience I am inclined to agree with him. Many people do not know that their breathing patterns are poor, and sometimes the only time they experience the detrimental effects of poor breathing is when they exert themselves, such as when running for a bus or climbing a flight of stairs.

This pattern of interference with the respiratory system can sometimes be traced back as far as the age of five or six, because this is when many of us start to adopt a bent posture while bending over school desks. We learn to breathe badly when we are forced to hold these constricted positions for a great many hours during our developing years. The poor posture that most of us developed from hunching over school desks not only causes graceless, uncoordinated or even clumsy movements, but also restricts our breathing, causing us to take in less air than is good for us.

Many of our detrimental respiratory habits may go unnoticed during childhood or adolescence, but the evidence of fast, shallow breathing can more easily be seen in adulthood as it becomes more ingrained and accentuated. In severe cases, it is possible to observe adults unnecessarily raising and lowering their shoulders while inhaling and exhaling, directly due to excessive tension around the ribcage. Others hold their abdominal muscles rigid and then lift and collapse the chest in order to breathe, because they are trying to sit up very straight or wrongly think that they should have a flat stomach. If we are unable to get enough oxygen because of unnatural interference in the workings of the respiratory system, we will unconsciously try to find another way of achieving a greater intake of oxygen. This is done by increasing the breathing rate, which results in a quicker, more shallow pattern of respiration.

By comparison, if you observe a baby or young child, you may notice how much the abdomen and ribcage move in and out rhythmically with each breath. The rest of the body remains in a state of relaxation while the air is taken in and expelled almost effortlessly. In fact, it seems like the whole body is breathing.

The way we breathe affects our state of mind, energy level, the way we feel emotionally and even the way we move. In the short term, a fast, shallow type of breathing does not cause harm, but in the long term habitually shallow or fast breathing can cause or exacerbate negative states of mind such as anxiety, worry, panic attacks and general stress. Any one of these conditions can in turn cause further interference of the breathing mechanism, and a vicious circle is created. If someone is anxious in a situation that requires calm and collected thought, we often tell them to ‘take a deep breath’ as a way of calming down. In the same way, by bringing our attention to the way we breathe, we can begin to become aware of and change the detrimental habits that interfere with this delicate process. By relearning our natural rhythm of breathing, we can alter the way we think, feel and act while carrying out our everyday activities.

When most people come for Alexander lessons, they do not specifically complain of breathing problems, and, if asked, they will say that their breathing is fine. However, I find that many people are breathing too fast, too shallowly or in an erratic manner; often they do not even give themselves time to finish one breath before they start the next. This is a direct reflection of how they have been living their lives, and they will frequently say that they feel that there are never enough hours in a day. This fast pace of life in which many people feel they are caught up causes over-tensing of many muscles and the associated restrictive breathing pattern, which causes harm to their physical health, their state of mind and their quality of life. After a course of Alexander lessons, I find that a person’s breathing rate usually decreases naturally, often by up to a third.

Today there are many schools of thought on how to improve breathing, but many of these ways involve some kind of breathing exercise, which in many cases unfortunately only encourages more bad habits and can do more harm than good. With all good intentions, many voice trainers and physical educators encourage ‘deep breathing’ as a way of getting the lungs to work more efficiently, and while their aim may be sound in principle, the way in which they encourage their students to achieve this may actually exacerbate many respiratory problems. People are often instructed to increase their lung capacity by ‘pulling in’ or ‘pushing out’ their breath, but this creates further pressure on an already overstrained muscular system. Breathing exercises commonly focus on the in-breath, as, for example, the instruction to ‘take a deep breath’, but this will invariably cause the person to tighten muscles and increase the interference with the entire breathing mechanism. Tightening and shortening the muscles can result in arching of the back and lifting of the chest, which causes additional faulty breathing patterns and makes the original breathing habits even more deeply ingrained.

In contrast, the Alexander Technique encourages more natural breathing by a process of unlearning detrimental habits, rather than practising specific breathing exercises. The late Dr Wilfred Barlow, an Alexander teacher and consultant rheumatologist working in the National Health Service in the UK, was convinced that the person suffering from asthma needed ‘breathing education’ rather than a set of exercises. In his book The Alexander Principle, he wrote: ‘The asthmatic needs to be taught how to stop his wrong way of breathing. Breathing exercises have, of course, frequently been given by physiotherapists for this and for other breathing conditions, but the fact is that breathing exercises do not help the asthmatic greatly – in fact, recent studies show that after a course of “breathing exercises”, the majority of people breathe less efficiently than they did before they started them.... the asthmatic does not need breathing exercises – he needs breathing education. He needs a minute analysis of his faulty breathing habits and clear instructions on how to replace them by an improved use of his chest.’

Over the last 20 years, many asthma sufferers have come to me for help with breathing and I have found that they can learn to breathe more freely by improving their overall posture. Due to the benefits of the Technique, many have dramatically reduced or stopped their medication (while under their doctor’s supervision).

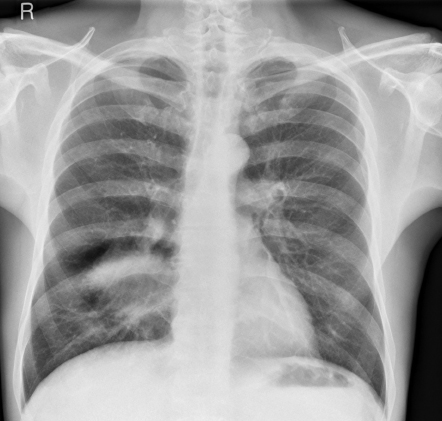

Without making it too complex, it might be helpful to have a basic understanding about how the respiratory system works. The lungs are among the biggest organs in the body. Our total lung capacity ranges from 4 to 6 litres (7 to 101/2 pints), and we breathe approximately 11,000 litres (2,420 gallons) of air in any one day. The lungs are enclosed within a mobile ribcage: the very top of the lung is actually situated above the collarbone and the bottom of the lung extends almost to the bottom of the ribcage (See photo 49). Just below the lungs is a very powerful muscle called the diaphragm, which is crucially involved in the process of breathing. It is a large dome-shaped muscle that is attached to the lowest ribs.

When you breathe in:

The diaphragm contracts, causing it to lose its ‘dome’ shape as it moves downwards and flattens out, making the area within the ribcage expand. At the same time the lower ribs move outwards. These actions allow more room in the thoracic cavity, so that the lungs have a greater capacity to receive air. When the diaphragm is stretched to a certain point, a ‘stretch reflex’ is triggered and it, automatically and without us having to do anything, starts to return to its original dome shape.

When you breathe out:

The exact opposite happens: the diaphragm relaxes and returns to its dome shape, causing the capacity within the ribcage to decrease. The sternum drops and the lower ribs move inwards. This has an overall effect of reducing the area in the thoracic cavity and causes the lungs to expel air. As we exhale, the air pressure in the lungs decreases, creating a partial vacuum, which then causes the air from outside to be sucked into our lungs automatically and without us having to do anything. This causes the diaphragm to contract, and it starts to move downwards once again, thus completing a natural cycle. Under normal conditions, the entire breathing mechanism should be self-governing and therefore is sometimes referred to as working ‘automatically’. Contrary to what many people think, it is the out-breath, rather than the in-breath, that determines the way we breathe, yet many exercises focus on ‘taking an in-breath’ rather than allowing more air to be released. In fact, the more air we exhale, the deeper the next inhalation will be, and the deeper our breathing will become. So the first thing you need to do to improve your breathing is to allow yourself to finish one breath before you start to breathe in. It is important to remember that you should not force the air out, because this also causes excessive tension and interferes with natural breathing.

49: The lungs, as shown as darker area, are much bigger than many people think. They extend from above the collarbone to almost the bottom of the ribs.

Alexander was a trained reciter, and efficient breathing was essential to his skilful recitation. He helped people to breathe more easily during their lessons with him. He was famously quoted as saying: ‘I see at last that if I don’t breathe... I breathe’, because his Technique is based on ‘doing less’ – that is, instead of willing oneself to breathe in a certain way, the key is rather to stop interfering with the natural breathing process, so that it can happen naturally by itself. Relearning how to breathe freely can be very beneficial to public speakers or indeed anyone involved in the performing arts, because many speakers, actors and musicians become nervous before or during a presentation, concert or performance, and nervous tension can adversely affect the way they perform, in extreme cases even preventing them from performing altogether. By ensuring that we breathe naturally, we can effectively combat the effects of stress. In this way, we will feel calmer and more in control even at times of intense emotional or mental stress.

Just by focusing your attention on how you breathe without trying to change it, you can bring about an improvement. Take a moment and begin to be aware of your breathing as you are standing or sitting. Ask yourself the following questions:

• How rapid is my breathing?

• How deeply do I breathe?

• Are my ribs moving as I breathe?

• If so, which part of the ribcage is moving most?

• How much movement is there in the abdominal region when I breathe?

• Do I feel any restriction in my breathing, and if so, where?

It is crucial that you do not deliberately alter the way you breathe; just simply become aware of the inhalation and the exhalation, as this is often enough to bring about a favourable change. Becoming aware of tension is the first step in learning how to breathe more naturally.

To help his pupils relearn how to breathe naturally, Alexander developed the following method, which is known as the ‘whispered ah’ procedure. He always maintained that he did not like using exercises as they could encourage habits and could have the effect of stopping people thinking for themselves, so he developed the following procedure and maintained that it was essentially an exercise in inhibition and to prevent ‘end-gaining’ while breathing.

1. First of all, take a moment use your directions as set down earlier in the book.

2. Notice where your tongue is and let it rest on the floor of the mouth with the tip lightly touching your lower front teeth. This allows for a free passage of air to and from the lungs.

3. Think of something amusing that makes you smile, because that mental act lifts the soft palate, which helps to create an unrestricted passage for the air to flow freely. It also can help your lips and facial muscles to release tension.

4. Gently and without straining, let your lower jaw drop so that your mouth is open. If you allow gravity to do most of the work, your head will not tilt backwards in the process.

5. Whisper an ‘ah’ sound (as in the word ‘laughter’) until you come to the natural end of the breath. It is important not to rush the procedure by forcing the air out too quickly or trying to empty the lungs by extending the ‘ah’ sound as long as possible. Gently close your lips and allow the air to come in through your nose and fill up your lungs.

6. Notice if you have tightened in some areas while whispering the ‘ah’.

7. Repeat this procedure several times.

Be aware of your breath as it travels in through your nose, down your throat and into your lungs. Just being conscious of your breathing will bring about subtle changes of which you may not even be aware. Again, it is important to remember that trying to change your breathing in any way will interfere with the body’s natural processes. You may also like to use other whispered sounds, like ‘ee’, ‘oo’ or ‘sss’, and you can vocalize these sounds too. On inhalation, the air has to travel horizontally through your nose – many people think that the air direction is up the nose, but examination of the bones of the skull shows that the nasal passage is in fact a horizontal opening.

You can try this for yourself. Take a deep breath, imagining the air travelling up your nose, and now do the same but imagining the air travelling horizontally through your nose. You will probably find the second breath takes much less effort. Some people also find it helpful to imagine breathing in through the eyes, as this can help prevent tightening of the neck or throat muscles during the ‘whispered ah’ procedure.

Regular practice of the ‘whispered ah’ can help you to free yourself from harmful breathing habits and can, over time, help you to develop a more efficient respiratory system. Once again, it is strongly recommended that initially you go through this routine with your Alexander teacher, as it is easy to misinterpret the instructions. Also, due to faulty sensory appreciation it is often the case that we maybe tensing our muscles unconsciously. In other words, when we are following these instructions we may be doing something else without realizing it. For example, it is very common for people to pull the head back onto the spine instead of just allowing the jaw to drop while carrying out the third instruction, while others are convinced that they are opening their mouth wide when there is actually a gap of less than 2cm (3/4 in) between their upper and lower lips. If for any reason you are unable to have lessons (for instance, because there is no teacher near you), then it is important to perform the ‘whispered ah’ in front of a set of mirrors, as this will give you a better idea of whether or not you are carrying out the instructions correctly. Remember: natural breathing is an involuntary process, and when we don’t interfere with it, breathing will take care of itself.

Many people are unaware that speaking and singing involve the whole self, and both of these activities are adversely affected by poor posture. If we want to learn to speak or sing effectively and confidently, we first need to be sure to eliminate the voice’s most powerful obstacle, namely muscle tension. To ensure that our voices are being produced in the most effective and efficient manner, the first thing we need to consider is the way we are using ourselves during the activity.

The way we breathe during all acts of voice production, including conversational speaking, is of paramount importance. The lungs act like bellows, forcing air up through the larynx, where the vocal cords are located, causing them to vibrate. This sound is then amplified in the cavities of the head, and the tongue, the palate, teeth and lips articulate and impose consonants and vowels on the amplified sound. This sound will be affected if the body is being pulled out of alignment due to excessive tension in the muscles. Try making a vocalized ‘ah’ sound, then drop your head before pulling it back onto your spine and you will see that your voice changes significantly. In this way you can see that even the way we speak is affected by our posture.

Natural breathing is not only an essential part of existence – it can also be one of life’s great joys. It can be a pure pleasure to feel the air filling you with life and offering you the gift of yet another moment to appreciate its wonders. The Italian poet and novelist Giovanni Papini once said that breathing is the greatest pleasure in life. Being aware of your breathing and practising the ‘whispered ah’ regularly can be a powerful way to calm your entire system and allow you to be in the present moment to experience the true miracle of being alive.

By allowing your breathing to return to its natural rhythm, it will become deeper and freer, and your body will start to function more efficiently. Many people feel ‘energized’ with a renewed enthusiasm for life as they feel the power of their spirit flowing through them. With every breath comes another opportunity to throw away the habits that bind us so tightly, so that we can start to make real choices in our lives. Through free choice we have the power to turn life into what we want it to be, rather than spending it constantly chasing endless goals. So perhaps these wise words of Thich Nhat Hanh can do wonders for your posture: ‘Smile, breathe and go slowly.’