“It has taken the American public a long time to swallow its chop suey,” noted a reporter in 1908 on the mounting popularity of Chinese food in America.1 Indeed, it had been largely shunned by American consumers for almost fifty years after its initial landing in California. This dramatic turn of events for Chinese cooking came as a result of two new developments: (1) a profound demographic and socioeconomic transformation of Chinese America, and (2) the extraordinary expansion of the American economy. At the conjunction of these developments is Chinatown’s metamorphosis from a target of intense racial hatred to a popular tourist destination.

The growing appeal of Chinatown among non-Chinese leisure and pleasure seekers was not a development to rejoice over in Chinese American history. This phenomenon followed the destruction of most of the once-thriving rural Chinese communities, and the subsequent urbanization and occupational marginalization of the shrinking Chinese population.

At the same time, turning the United States into a global power, the fast-growing economy at home generated more wealth and leisure as well as a swelling army of tourists, hungry for new things to see and to savor. A steadily increasing number of these travelers, especially those in the lower-middle and working classes, went to Chinatown to sightsee. It is in Chinatown that many American mass consumers discovered Chinese food.

THE AMERICAN ECONOMIC EXPANSION

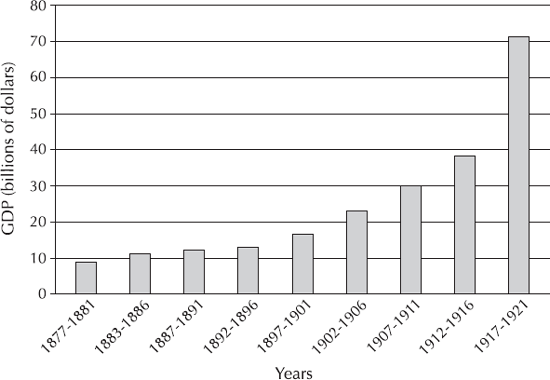

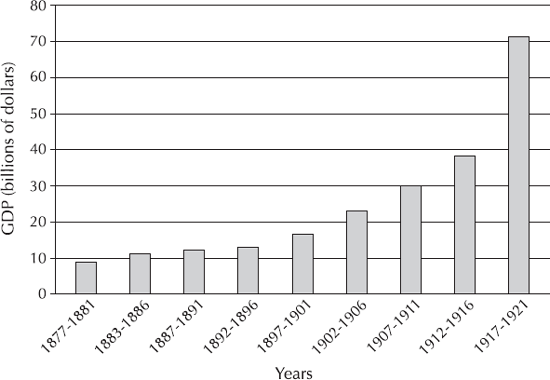

The quickly improving U.S. economy and standard of living in the late nineteenth century prepared a larger economic context for the spread of Chinese food. Analogous to the economic miracle taking place in China in the late twentieth century, in the last three decades of the nineteenth century, U.S. manufacturing increased at an annual rate of about 8.7 percent, and the economy at about 7.4 percent (figure 3).2 Measured in 1985 USD, the American gross domestic product per capita increased from $2,254 in 1870 to $3,757 in 1900 and $4,559 in 1910.3 During World War I, the United States became the world’s largest creditor and leading export nation.4

Needless to say, the economic expansion did not equally benefit all social classes and racial groups. From 1923 to 1929, another period of economic prosperity, the share of total income received by the wealthiest 1 percent increased by 35 percent while the wages of unskilled workers actually declined. Still, many groups benefited from the economic growth. In the years after 1890, for example, the white elderly saw their incomes rise sharply.5

FIGURE 3 The growth of the GDP (gross domestic product) of the United States, 1877–1921. (U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1957 [Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1960], 143)

Charles S. Maier has correctly pointed out that America “began its ascent to global power in the late nineteenth century pursuing its industrial vocation.”6 That ascent was also accompanied by soaring consumer desires. With more money in their pockets, a great number of Americans developed a lust for leisure travel. The middle and upper-middle class joined the wealthy in trips to see the world. After the Civil War, a few visits to Europe within a lifetime became a sign of the American bourgeoisie, including an education tour for adolescents and a requisite wedding trip.7 The lower echelons of society also sought to jump on the bandwagon of leisure travel. The sociologist Dean MacCannell sees the turn of the twentieth century as the beginning of mass tourism. His focus is on “the international middle class,” but in the United States the leisure travel craze also reached less privileged groups like immigrants and minorities.8

Unable to afford the time or money for long-distance travel, less-fortunate segments of society took short and inexpensive excursions within American cities, and these trips became increasingly popular around the turn of the century. Although the “raw, young American cities were barren of classical history and art,” they had certain attractions to offer.9 Among them were the ethnic communities with exotic appearances and smells. The decades-long political and media focus on “the Chinese problem” had turned Chinatown into an exoticized urban ethnic community, one that emerged as a popular destination of urban excursions.10 In an article about New York City’s ethnic communities, Forest Morgan pointed out in 1910 that “in all New York the most bizarre and interesting colony is of course Chinatown. … This is a great locality for sightseers.”11

THE EMERGENCE OF CHINATOWN AS A TOURIST ATTRACTION

The emergence of Chinatown as a tourist site embodied a profound transformation of the demographic and occupational character of America’s Chinese population, altering the meaning of Chinatown for white Americans and the Chinese alike.

This transformation took place on three fronts. The first was the disappearance of Chinese communities in small-town America. For many people, the word “Chinatown” invariably invokes the Chinese settlement in large cities. But for years after the Gold Rush, the American Chinatown existed in both small towns and big cities. Things changed quickly after the early 1870s, when the anti-Chinese movement became more intense and violent, and garnered widespread support throughout society. Signaling the beginning of a long-lasting wave of anti-Chinese violence, an anti-Chinese riot broke out in Los Angeles in 1871, resulting in the deaths of nineteen Chinese.12

In what Jean Pfaelzer insightfully calls “the forgotten war against Chinese Americans,” the anti-Chinese movement did not succeed in eradicating the entire Chinese presence, but it destroyed about two hundred Chinatowns in the Pacific Northwest and drove out their residents by the end of the 1880s.13 The Rock Springs massacre in 1885 reveals the level of anti-Chinese brutality and the acquiescence it received. In one of the worst racial riots in American history, fifty-one Chinese laborers, who worked in the coal mines along the Union Pacific Railroad in Rock Springs, Wyoming, were killed.14 While the perpetrators went unpunished, the survivors of the ruined Chinese community were forced to leave. In 1887, more than thirty Chinese miners perished in another massacre that took place in Oregon’s Hell’s Canyon Gorge on the Snake River. The criminals, who “robbed, murdered, and mutilated” the Chinese victims, remained free of convictions.15

As the survivors of such attacks in small towns moved to Chinese communities in cities in both the West and the East, Chinese America began to be urbanized. In 1880, those Chinese living in cities with a population of at least 100,000 represented only 21.6 percent of the Chinese population. That amount grew to 71 percent in 1940.16 For the Chinese, then, the transformed Chinatown in the American metropolis was no longer merely a cultural, socioeconomic center within Chinese America. It had come to epitomize Chinese America.

The second significant change in Chinese America was its occupational concentration in the service sector of the economy. This was largely because the anti-Chinese forces that ravaged small-town Chinese communities also pushed the Chinese out of the more profitable occupations, such as mining and manufacturing. By 1940, restaurant jobs had become one of the two main lines of work for the Chinese.

The third transition occurred in the minds of Americans, for whom Chinatown shifted from primarily a target of hatred to an object of curiosity, and from a place of danger to a site of pleasure. For much of the second half of the nineteenth century, a host of white Americans—including labor union members, public health officials, politicians, and reporters—had concertedly created the image of the Chinese as a grave threat. In a widely distributed and cited pamphlet, the prominent physician Arthur B. Stout regarded the Chinese community as a potential cause of the physiological “decay of the nation”;17 others depicted Chinatowns in cities like San Francisco as dark places of immorality and sources of sexually transmitted diseases and epidemics.18

The nineteenth-century American city itself was not a very desirable place. “Walking into an American city in the mid-nineteenth century,” the historian Catherine Cocks tells us, “was an act fraught with moral and political peril.”19 But in the minds of white Americans, walking into an urban Chinatown entailed unknowable physical hazards, even though it had never been a threat to their physical safety. Quite often, white visitors to Chinatown in San Francisco requested a police escort for protection “against the possible dangers.”20 Some depicted Chinatown as New York’s “most forbidden quarters.”21

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, the sense of danger and the intensity of enmity regarding Chinatown began to subside, replaced by growing curiosity because the perceived threat of the Chinese had been curbed and controlled. The various exclusion measures, starting with the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), had virtually shut the door on Chinese immigration. Showing the effect of such measures, in 1890 the Chinese population in the United States started its long downturn. In 1904, when Congress made Chinese exclusion a permanent policy, even the notoriously anti-Chinese Democratic Party in California felt—for the first time in its history—no need to mention the Chinese issue in its platform.22 The anti-Chinese forces simply cleansed Chinese settlements from the open space of small-town America. Now safely contained in the confines of a few urban blocks in major cities, the Chinese community became a pleasurable site and a tourist destination for those eager and curious to see and taste the Orient.

America’s curiosity about China was not a new development and had often associated Chinatown with China and all things oriental since the early 1850s.23 For Easterners, in particular, Chinatown represented a unique feature of the American West before its creation in East Coast cities. A. W. Loomis suggested in 1868 that people would learn about how the Chinese lived “without the trouble and expense of a voyage by sea” by visiting Chinese stores and restaurants in California.24 During their visit to San Francisco in 1873, a group of Philadelphians took a tour of Chinatown, which “they regarded as good as a trip to China.”25

Beginning in the 1880s, there was a new development: Chinatown as a specimen of China became its predominant image and social utility. Contemporaries noticed a “remarkable” change: the softening of the popular prejudice again the “once hated and despised” Chinese.26 San Francisco’s Chinatown was the first Chinese settlement to emerge as a significant urban travel destination. From time to time, Chinatown residents would spot VIP visitors. When Rutherford B. Hayes visited the city in 1880—the first U.S. president to do so—he took a trip to Chinatown. In 1881, a group of “distinguished French visitors” paid a visit to the city’s Chinese quarters “under the escort of the Chief of Police.”27 In September 1882, during his stay in San Francisco en route to British Columbia, the Marquis of Lorne, governor-general of Canada, and his wife made a trip to Chinatown, where they watched a performance in a theater for a half hour before heading to the Pen Sen Lan restaurant for Chinese food and tea.28 Prominent domestic travelers also visited Chinatown. In June 1885, the editor of the New York Tribune toured Chinatown, accompanied by members of the city’s board of supervisors and “the usual escort of detectives.”29 By the 1890s, as tourism traffic increased, visiting Chinatown was no longer primarily for special occasions (such as the Chinese New Year) but occurred more regularly, and tour guides had replaced police escorts.

In New York, Chinatown tours became a frequent occurrence around the turn of the century. Chinatowns in many other cities, such as Chicago and St. Louis, also witnessed an increase in tourist traffic.

Visitors and tourism promoters now characterized Chinatown as a place for “harmless” entertainment.30 So harmless, indeed, that taking a Chinatown tour turned into a “constantly growing practice,” and sometimes even a family event. A Chinatown sightseer by the name of M. H. Cross wrote to the New York Times that “the usual Chinatown tours are interesting and harmless.” He noted, “I have taken my wife and daughters and young lady visitors; I have made at least one trip under the guidance of ‘Chuck’ Connors. I have never seen there anything which a young woman might not properly see.”31 Born George Washington Connors, “Chuck” made a career and became famous by conducting Chinatown “vice tours.”32 His staged scenes brought Chinese vices, which had become proverbial in the media, in front of the bare eyes of his visitors, free of risk.

A passage from a San Francisco city guide of 1897 reveals the stimulatingly paradoxical appeals of Chinatown to white tourists: “If the average citizen of San Francisco were asked to place his finger on that part of his city which is the most attractive to strangers and at the same time the most objectionable to himself, he should be sure to indicate Chinatown.”33

Objectionable because it had long been regarded as a “vice district.”34 In San Francisco, it was part of the red-light district known as the Barbary Coast, and in San Diego, it was located in a similar neighborhood called the Stingaree.35 Objectionable, yet “Chinese vice” constituted a major attraction of Chinatown. For many non-Chinese visitors, part of the pleasure and sensation of visiting Chinatown was to experience a sense of superiority, culturally and morally. In their eyes, Chinatown stood in sharp contrast with white society: progress versus stagnation, vice versus morality, dirtiness versus hygiene, and paganism versus Christianity. A French visitor to Chinatown put it bluntly in 1880: “We have seen to night what we have never seen before, and what we hope never to see again.”36 Clearly, touring Chinatown gave some visitors a feeling of superiority.37 For this purpose, Chinese scenes or “mini-Chinatowns” were staged by the budding tourism industry not just in New York but also in other cities like San Francisco to magnify the moral inferiority of the Chinese. In 1910, New York City closed one such make-believe Chinatown that had long been on Doyers Street when it became too unsanitary.38 Nonetheless, the fake opium den continued to exist there for many years.

Pork Chop Suey

Serves 1 or 2

When Chinese restaurants started to venture outside Chinatowns, chop suey became the most famous line of dishes. It remained a synonym of America’s Chinese food for decades. However, its origin has been shrouded in mystery. Cooking it can help us better understand this simple and versatile traditional Chinese dish, which has become a quintessential American story.

2 tbsp cornstarch

1 tsp sugar

1 tbsp water

1 tbsp rice wine

1 tsp sesame oil

3 tbsp light soy sauce

dash of black pepper

1 lb lean pork, sliced into thin strips

4 tbsp olive oil

1 tbsp chopped green onion

1 clove garlic, minced

¼ tsp salt

3 cups sliced napa cabbage

4 cups (soy) bean sprouts

⅓ cup diced celery

1 cup shredded carrot

4 button mushrooms, cut into wedges

½ cup chicken broth

Mix the cornstarch, sugar, water, rice wine, sesame oil, soy sauce, and black pepper in a bowl. Add the pork and marinate for 1 hour. Heat 2 tbsp olive oil in a wok or nonstick frying pan, and add the green onion and garlic. Stir for about 10 seconds.

Add the marinated pork. Stir until cooked. Transfer it to a clean container and set aside. Heat the remaining 2 tbsp olive oil, and add the salt and then the cabbage, bean sprouts, celery, carrot, and mushrooms. Stir for 2 minutes or until almost cooked. Put the pork back in the wok and add the chicken stock. Stir thoroughly and bring to a boil.

We can easily envision the cultural and moral superiority that many white visitors to Chinatown felt when riding at night in hay wagons and listening to white tour guides like Chuck Connors, known then as the “mayor of Chinatown,” who declared that “these poor people are slaves to the opium habit and whether you came here or not to see them they would have spent this night smoking opium just as you see them doing it now.”39 White middle-class tourists in St. Louis also took such tours to the Hop Alley Chinatown. One tour on the night of January 4, 1904, included three couples and two single women. Like Chinatown sightseers elsewhere, they visited an opium den. Then they went to a Chinese restaurant, “where tea and chop suey were served.”40

In St. Louis and other major cities, evidently, vice was not the whole story behind the Chinatown tourism boom. Chinese food was one of the standard features of a “usual” Chinatown tour. Together with the temples, the theater, fake opium dens, and souvenir shops, Chinese restaurants played a critical role in supporting Chinatown’s tourism-oriented economy during the first half of the twentieth century, a role that is yet to be fully researched.41

Chinese restaurants represented an important tourist attraction, as the Washington Post observed in 1902: “The person who sets out to see sights of the Capital and fails to visit the Chinese restaurants misses one of the features of the city.”42 “Of all the places in Chinatown,” a newspaper report of New York’s Chinese settlement noted as early as 1888, “the most interesting are the restaurants.”43 Dining establishments were important for four reasons. First, they were extremely noticeable, visually and olfactorily. Second, they were less controversial than some other attractions, such as opium dens, which met strong objections among both Chinese and whites. Third, among all Chinatown attractions, restaurants were the most important generators of revenue as well as jobs. Peter Kwong reported in 1987 that fifteen thousand people worked in the 450 restaurants in New York’s Chinatown.44 To this day, according to a study of Chinese restaurant workers, restaurants are the largest employer of Chinese immigrants across the nation.45 And fourth, restaurants have been the most enduring features of Chinatown. Over the years, the opium dens have long faded away, and tourists’ interest in the temples, the theater, and even the shops has ostensibly waned, but the appeal of Chinese food has remained high. Even in the early years, many equated Chinese food with Chinatown. Helen Worden remarked in 1933, “If you prefer to bring Chinatown to your door, call either Mr. Chin or Mr. Lee at Chelsea 3–6840. They will deliver to your apartment for $3.00 a gallon some of the best chow mein I have eaten. This will serve sixteen people.”46

In cities without a substantial Chinese community, Chinese restaurants themselves functioned as a tourist attraction. Craig Claiborne, one of the most famous American culinary experts, grew up during the Great Depression in Mississippi, where “anyone’s idea of excitement and genuine adventure was a trip to a big town like Birmingham or Memphis.” In the 1970s, he recalled his first trip to Birmingham when he was seven or eight years old: “[T]he only thing I do remember about that trip” was “being taken to a Chinese restaurant. There were hanging Chinese lanterns and foreign waiters and real Chinese china and chopsticks and very hot and exotic tea.”47

Nonetheless, the popular interest in Chinese food was not a mere by-product of tourist curiosity about the exotic Orient. Otherwise, most Chinese restaurants would have stayed inside Chinatown, where visitors could also experience other exotic elements of Chinese culture, such as groceries, fish markets, and storefront shops. Instead, Chinese restaurateurs marched en masse to non-Chinese neighborhoods and communities. More than just a change in taste, the spread of Chinese food also signaled a profound transformation in lifestyle and the beginning of mass consumption in the realm of food. Accompanying an increasing desire for travel, more and more people coveted the convenience and luxury of having their meals cooked and served by others. As a result, average Americans’ expenditure on dining out also began to grow steadily and visibly around the turn of the century.48

Popularizing the dining-out experience, the ascent of Chinese food marked a significant domestic expansion of the empire of mass consumption. Richard Pillsbury regards fast food as the “first class of food” produced and consumed outside the home.49 But Chinese food is actually more deserving of this dubious honor. It is also the longest-lasting type of food for mass consumption at a national level. Representing a comparable case are the American diners, which appeared in the late nineteenth century and were also independent operations.50 During their prime in the 1940s, there were as many as six thousand diners in the country. But diners were mainly regional phenomena, concentrated in the Northeast, while Chinese restaurants multiplied from coast to coast. The diners began their decline in the 1970s, while the number of Chinese restaurants has continued to grow, dueling with American fast-food outlets and eclipsing even McDonald’s in number. Meals cooked and served by others had been an exclusive privilege enjoyed only by the social elites. Chinese food played a significant role in liberating this privilege from the monopoly of the wealth by turning dining-out into a universally accessible experience in cities across the nation.