Cookbooks tell stories, and so it is fitting to begin this chapter on Chinese cookbooks with a cookbook story.

A few years ago, after learning about my research, my mother showed me her modest cookbook collection. One, in a blue plastic cover, immediately caught my eye. As I opened the book, a few pieces of paper—handwritten recipes and food-ration coupons—slipped out from between the pages, resurfacing from an increasingly distant past.

It was one of the first few cookbooks I had seen my mother use. She got it in the early 1970s, when we had our first real kitchen and no longer had to cook in the passageway in front of our two-room apartment. The book added a few dishes to her repertoire, such as pan-fried eggplant and steamed pork with ground rice, but for the most part my mother used it for her reading pleasure and occasionally for keeping things like recipe notes.1 In those days of food shortages, many ingredients mentioned in the 496-page book were beyond our reach, and some—such as spaghetti, cream, bear’s paw, shark’s fin, and deer antler—my mother had never even seen or heard of. In sharp contrast to the asceticism of the Cultural Revolution, which demanded self-sacrifice, the book promotes good eating and gives detailed instructions on such issues as nutrition and food hygiene, which concern the well-being of the individual. Although the authors still had to justify the cookbook in the name of the revolution by inserting five Chairman Mao quotations on the first page, its publication was a clear sign that ideological radicalism had started to wane.

That book stands as a reminder of the multifaceted meanings of cookbooks as records of history—a uniquely valuable kind of historical record that connects larger socioeconomic currents to our personal experiences and existence.

The focus in this chapter is on Chinese-food cookbooks published in the United States up to the mid-1980s, when Chinese food became America’s most ubiquitous ethnic cuisine. Few have taken a comprehensive look at these cookbooks in spite of their apparently wide appeal.2 When I came to the United States in 1985, almost three hundred Chinese-food cookbooks had been published, many by major presses such as Macmillan, Crown, Doubleday, Grosset & Dunlap, Random House, Harper & Row, and Time-Life Books.3 Many of these titles saw multiple printings and editions. For example, the Vintage edition of Buwei Yang Chao’s How to Cook and Eat in Chinese, published in 1972, was the celebrated cookbook’s third edition. The restaurateur Wallace Yee Hong’s The Chinese Cook Book, which focused primarily on the recipes, went through eleven printings in the twelve years after its initial publication in 1952. Lesser known titles sometimes also saw multiple editions, including Clara Tom’s Old Fashioned Method of Cantonese Chinese Cooking, whose eleventh edition was published in 1983.4

Capitalizing on the mounting popularity of Chinese restaurants, the publication of Chinese-food cookbooks was another important vehicle that elevated the visibility of Chinese food differently from the way restaurants did it. Written mostly by Chinese American authors, moreover, these cookbooks serve as a parameter of that visibility and signified the critical role of Chinese Americans in introducing and promoting Chinese food. A close analysis of this style of cookbook writing also helps us better appreciate the meaning that Chinese food held for Chinese Americans. It afforded them a visible platform to speak to the American public. Chinese American authors talked not only about their food but also about Chinese history and culture and, in many cases, about themselves in prominent, proud personal voices. Therefore, Chinese-food cookbooks embody the confluence of important trends in the larger world and matters that are extremely personal to Chinese Americans.

In order to appreciate the value of Chinese-food cookbooks in a historical context, I look at historical cookbook writing in general, especially those in Chinese and American history, both of which significantly influenced cookbook writing by Chinese Americans.

“MUCH MORE THAN A COLLECTION OF RECIPES”

A “humble genre long neglected by professional scholars,” cookbooks are not just recipe collections but an especially valuable kind of historical document.5 They offer fascinating insights into both the private and public spheres, and illustrate the connection between them. This is because cookbook writing and reading are extremely personal endeavors that reflect prevailing ideas and trends in society.

Cookbooks are more than the culinary equivalent of laboratory manuals not because historians or literary scholars can dig out traces of the past or decipher aesthetic value between the lines of a culinary text with their academic tools and occupational idiosyncrasies. Cookbook authors themselves did not merely offer technical tips on cooking but often relayed their individual experiences, their sentiments, and their opinions about important social and political issues in the world around them.

Equally important, in reading cookbooks, readers are not simply looking for cooking advice. In fact, ample evidence suggests that there is no direct correlation between buying or reading cookbooks and cooking at home. The second half of the nineteenth century witnessed a significant increase in the publication of cookbooks in the Anglo-American world. Cookbook writers F. Volant and J. R. Warren wrote in 1860 that “it may be said that the world is inundated with cookery books.”6 There were already so many cookbooks that when publishing Jennie June’s American Cookery Book (1866), Jane Cunningham Croly felt compelled to ask: “Why another cook-book, when there are already so many?”7 Yet it was also during this period that dining out emerged as a noticeable recreational activity. Such a non-symbiotic relationship between the volume of cookbook sales and the frequency of home cooking became more pronounced over time. During the late twentieth century, Americans cooked less and less than in earlier decades, a fact confirmed by the numerous focus groups I have conducted and by the continued expansion of the restaurant industry. By the end of the twentieth century, dining out had grown to be the top leisure activity for adults, who spent about half of each food dollar away from home.8 At the same time, ironically, the sales of cookbooks skyrocketed. In the United States, the world’s leading market for cookbooks, about 530 million books on cooking and wine were sold in 2000, representing a 9 percent annual increase from 1996.9 American consumers’ craving for cookbooks has not subsided. “Cookbooks are the second largest category for adult non-fiction,” a senior executive of a leading book research company reported recently.10 This is because the cookbook has been “much more than a collection of recipes,” as a leading cookbook publishing company proclaims.11

The personal nature of cookbooks is apparent, as manifested in their multifaceted intimate attachment to individual users. Families often have their own cherished books, and many people—ranging from my mother back to Victorian-era Americans—love to compile recipe scrapbooks. Readers also tend to use cookbooks not just in the kitchen but also in the bedroom, where cookbooks have become “a favorite bedtime reading.”12

For countless authors, writing about food is also an important vehicle to express the self. Traci Marie Kelly identifies three kinds of food writing as “culinary autobiographies”: culinary memoirs, autobiographical cookbooks, and autoethnographic cookbooks.13 In the early years, such writings created precious opportunities for women to share and record their feelings and experiences. Along with diaries and journals, cookbooks have become vehicles for women “to recount and enrich their lives.”14

Finally, cookbooks are indeed personal because food itself is so essential to each human being. Cookbooks, therefore, often directly address important individual issues, such as health, which remained a prominent theme in historical food writings in both China and the United States.

Cookbooks are also social texts. First, the knowledge in a cookbook reflects the collective wisdom and experiences of communities more than the individual ingenuity of the author. In fact, the very word “recipe,” which is from the Latin recipere (“take” or “receive”), has connotations of exchange. Cookbooks are repositories of private know-how, making it available to the public. Second, cookbook writing is closely tied to social conditions and trends. In an article published in the magazine Restaurants USA, David Belman characterizes American cookbooks as “historical treasures, commercial phenomena and some of the most accurate gauges of the culinary state of the country.”15

Some Chinese cookbooks, especially those published in the earlier decades of early and the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), further illustrate the importance of cookbooks as historical documents that embody the confluence of the personal and the social. As is the case of food writing in other contexts, early Chinese authors did not write cookbooks with the sole intention of offering cooking advice. Rather, they harbored strong concerns about the well-being of the individual as well as society.

There is no consensus on exactly when the first cookbook appeared in China in part because people have different notions of what constitutes a cookbook. Some regard Cui Hao Shi Jing (Cui Hao’s Culinary Classics), which was attributed to the fifth-century statesman Cui Hao, as the country’s first cookbook in part because it “concerned itself mainly with the daily preparation of foods and not with medical application of foodstuffs.”16

In fact, interest in the health ramifications of food actually constituted a major aspect of ancient Chinese food writings. It reflected the impact of Daoism (or Taoism), which focuses on human individuality, including bodily health. Early Chinese food writing also stemmed from agronomic texts, which were heavily influenced by Confucianism. This influence helps to explain the attention that many early Chinese cookbooks paid to the collective welfare of society.17 Thus some Chinese American cookbook writers were keenly aware of the impact of Daoism and Confucianism on Chinese cookbook writing.18 And in many cases, they also invoked early Chinese cookbook authors as a source of inspiration and authority.

In China, the initial drive for recipe writing and collecting came not simply from a preoccupation with cooking technicality per se but from concerns about both the individual and society. The emphasis on food as a means to maintain the health of the individual remained a prominent feature in Chinese cookbooks for centuries. In these cookbooks, considerations about health often outweigh details about cooking. One such book, Yin Shan Zheng Yao (The Essentials of Food and Beverage), is a palace-food handbook written in 1320 during the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). Its opening chapter details various food-related contraindications, and many of its elaborate recipes focus on the health aspects of the dishes.19 The book’s aim was to use food for yangsheng. Meaning “nourish life” in Chinese, this term conveys an understanding among the Chinese of the ultimate purpose of food. And it has persisted as a compelling motif in Chinese cookbook writings since then. Another cookbook, Yinshi Xu Zhi (All You Must Know About Food), written by Jia Ming at the beginning of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), introduced the medicinal properties of more than three hundred foods. He wrote in the introduction that diet is a way to yangsheng. The recipes in the food segment of Gao Lian’s Zun Sheng Ba Jian (Eight Treatises on the Principles of Life), written in 1591, were also mainly for the purpose of yangsheng. He began the treatise by proclaiming that “food is the foundation of human life.… The movement and function of the body’s Yin and Yang as well as and the mutual enforcement of its five elements are based on diet.”20

Even those that are seen as “pure” cookbooks frequently stressed the importance of food for yangsheng. Yang Xiao Lu (The Little Book on Nurturing Life) is one such book, written by the Chinese doctor Gu Zhong in 1698 in the early Qing dynasty. In the introduction, the editor Yang Gongjian pointed out that the purpose of diet was to preserve life.21 Meanwhile, he also exhorted readers to refrain from killing animals excessively and to be frugal. In his own introduction, Gu himself categorized people into three groups: those seeking quantity, for whom more food was better, and those pursuing tasteful and exotic food and vainglory without considering the cost or the harm to others. The third were people who ate to achieve the goal of yangsheng and kept their food clean and harmonious without being extravagant. In praising the third type, he was promoting the Confucian lifestyle and the virtue of modesty and self-discipline.22 Such efforts to encourage proper moral behavior and Confucian social values are also found in other cookbooks.

Also written in the early Qing, Zhu Yizun’s Shi Xian Hong Mi (The Grand Secrets of Diets) is another cookbook with a strong focus on cooking, especially Zhejiang cooking. But in it, readers would find discussions of the medicinal properties of foodstuffs, therapeutic recipes, and a long list of foods to avoid for health reasons. Equally interesting is a statement in the book’s introduction, written by a famous general by the name of Nian Xiyao: “[F]ood concerns the morals of society.”23 Edited by his son in the late eighteenth century, Li Huanan’s Xing Yuan Lu (Records of the Xing Garden) also has a clear concentration on food preparation itself. In the introduction, nevertheless, Li reminded readers that reading writings about food could help them avoid food poisoning, and he reiterated the moral teaching in the Confucian text Liji (Book of Rites) that emphasized the importance of honoring and serving parents as one’s social and familial duty.24

Chinese cookbooks performed another important historical and social task, which was to develop Chinese food into a culinary system that would transcend local and even regional boundaries—and in so doing, they served to further the cultural coherence of the country. Such an effort became particularly evident in food writings in the mid-Qing. Through the recipes they compiled and constructed, early and mid-Qing writers presented a cuisine not merely for the wealthy alone. The use of vernacular language and the inclusion of ordinary dishes in several early Qing cookbooks demonstrate an apparent attempt to address broad audiences.

A case in point is Yuan Mei’s Suiyuan Shidan (Food Menu of the Suiyuan Garden, 1792), a cookbook mentioned by numerous Chinese American food writers and that embodies a systematic effort to gather and organize culinary knowledge. The author spent forty years traveling to different parts of the country and tasting various foods. The recipes he collected encompass eastern and southern Chinese cooking, and many of them came from his own tasting experiences. The book also shows a thoughtful and deliberate attempt to elevate the appreciation of food to a theoretical level. In the introduction, Yuan cited Chinese classics, including Confucian texts, to illustrate the importance of food. He emphasized the subjectivity in taste and the imperative of personal participation for enhancing one’s ability to appreciate food.25

In the first part of his cookbook, Yuan theorized principles in dining and cooking, listing twenty things as “must-knows” (xuzhi) and fourteen practices to avoid. The culinary principles he outlined cover topics like the importance of ingredient selection, sauces and seasoning, timing in cooking (huohou), flavor and color, cooking and serving utensils, the sequence in serving food, seasonality of food sources, and cleanliness. Among the things to avoid are animal cruelty and indulgence in drinking alcohol.

Yuan could have not completed Suiyuan Shidan without the extraordinary contributions of his cook, Wang Xiaoyu. When Yuan tasted good food in someone’s home, he would send his cook there to learn the recipe. Wang, as master chef in Yuan’s kitchen, did all the shopping and cooking, and also demonstrated remarkable knowledge of China’s culinary tradition. After Wang’s death, Yuan wrote an essay to commemorate him, concluding that his wisdom was useful for elevating both people’s lives and learning.26

Mid-Qing food writers like Yuan Mei did not fully accomplish the task of articulating Chinese cooking, however. Showing his awareness of the distinctiveness of the cooking of the Han people, Yuan mentioned the differences between Han and Manchu cooking—the Han had a proclivity for soup-style dishes, while the Manchus tended to boil and stew their food.27 But he did not verbalize what made China’s food particularly Chinese, especially in comparison with Western food, in spite of his knowledge of it. Like Yuan Mei, Li Huanan was familiar with Western food and identified it as xi yang (western seas).28 But the presence of Western food, or any other foreign food, was not significant enough to magnify the Chinese-ness of China’s diet. The task of articulating the meaning of Chinese cooking, which had been left unfinished by those early Chinese food writers, would be carried out more comprehensively by Chinese American food writers in the twentieth century. They did so by putting Chinese food in direct comparison with American cooking, a system that they also knew very well.

Resonating with the theme of yangsheng in Chinese food writing, late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century American cookbook writers defined food in terms of its importance to bodily health. Fannie Merritt Farmer’s The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book (1896), for instance, defined food as “anything that nourishes the body.”29 In her celebrated The “Settlement” Cook Book (1901), Lizzie Black Kander reiterated Farmer’s definition.30 What sets American authors apart from their Qing counterparts is that their approach to healthful diet was influenced profoundly by natural sciences. Showing this influence, Farmer offered the following characterization of her book: “It is my wish that it may not only be looked upon as a compilation of tried and tested recipes, but that it may awaken an interest through its condensed scientific knowledge which will lead to deeper thought and broader study of what to eat.”31 This scientific interest in food also triggered mainstream America’s first in-depth publications on Chinese food, particularly soy beans and Chinese vegetables.32

Scientific perspectives continued to exert a noteworthy influence on food writing. The first edition of Good Housekeeping Everyday Cook Book (1903) starts with a classification of food in scientific terms: “All foods are divided into two classes, the nitrogenous, or those which contain nitrogen, and the non-nitrogenous, or those that do not contain nitrogen. The nitrogenous are divided into two classes, the albuminoids or proteids, and the gelatinoids.”33 The opening chapter of the seventh edition, published in 1943, offers extensive nutritional information as the basis on which to prepare healthful meals.34

Also like the aforementioned Chinese cookbooks, early American cookbooks reflected prevailing social currents, including Protestant and Victorian notions about family life and gender roles, and the cult of scientific perspectives. In fact, Harriet Beecher Stowe and her sister Catharine Beecher praised and promoted Protestant Victorian values and virtues such as frugality and domesticity in their influential The American Woman’s Home (1869), calling for “a Christian house; that is, a house contrived for the express purpose of enabling every member of a family to labor with the hands for the common good, and by modes at once healthful, economical, and tasteful.”35

Such cookbooks conformed to and reinforced the longtime historical reality and idea that home cooking was mainly the responsibility of women. Amelia Simmons’s American Cookery (1796) was heralded as “the first truly Americanwritten cookbook.”36 It was written for female orphans like herself, forced to work as domestics by “unfortunate circumstances.”37 In time, married women and young brides would become another targeted audience. Kander’s cookbook has a telling subtitle: The Way to a Man’s Heart. In 1918, the Boston Globe published The Boston Globe Cookbook for Brides, and its opening chapter is titled “How to Cook for a Man.” “It takes love,” the editor noted.38

Cookbooks are not just reflections of existing trends and conditions but have also been used to effect social change and forge communities. Kander published The “Settlement” Cookbook in order to raise funds to aid Jewish immigrants, and royalties from its sales supported various activities of the first settlement house in Milwaukee. The book exemplified similar fund-raising efforts by various groups, such as women’s clubs, religious and political organizations, and ethnic associations in order to promote their causes and build a sense of community.39

The community that Kander tried to build was local and ethnic. But cookbooks were also related to creations of national communities in contexts beyond China and the United States. Scholars such as Benedict Anderson have noted the critical role that the printing press played in fashioning modern national consciousness.40 First appearing in the fifteenth century, cookbooks were among the earliest printed books in Europe. In postcolonial India, Arjun Appadurai writes, the proliferation of cookbooks as “structural devices for organizing a national cuisine is accompanied by the development of a sometimes fairly explicitly nationalist and integrationist ideology.”41 Jeffrey M. Pilcher writes about the role of food in Mexico’s search for national identity; he points out that nineteenth-century Mexican cookbook writers frequently resorted to “blatant nationalist language” in an effort to “foment patriotism at home.”42

ANOTHER MILESTONE IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF AMERICAN CHINESE FOOD

Because of the importance of cookbooks as historical sources, we cannot fully appreciate the saga of Chinese food in America without understanding the cookbooks that articulated and promoted it. Along with the spread of Chinese restaurants, the proliferation of Chinese-food cookbooks stands as another vital milestone in the development of America’s Chinese cuisine.

The appearance of Chinese-food cookbooks was not synchronized with the rise of Chinese restaurants. If we do not count the two pamphlets published by the Department of Agriculture, on soy beans and Chinese vegetables, at the end of the nineteenth century,43 Chinese-food cookbooks did not appear until the 1910s, nor did they attract the same kind of attention as the fast-advancing Chinese restaurants did in the first two decades of the twentieth century. The time lag between the restaurants and the cookbooks is not difficult to understand: American restaurant-goers, who wanted to avoid cooking chores, had no reason to hurry to learn to cook Chinese in their home kitchens. The slow arrival of Chinese-food cookbooks is also consistent with a point made earlier in the book: American visitors to the Chinese restaurant were interested more in its convenient and inexpensive food than in the cuisine of China.

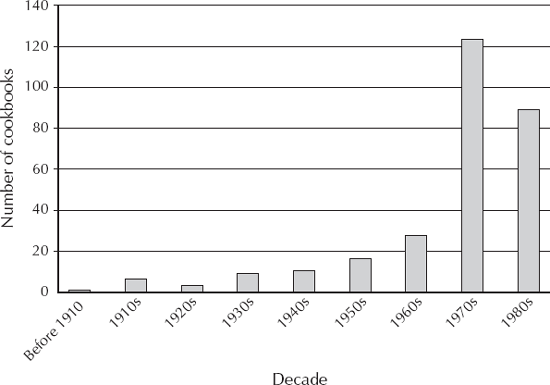

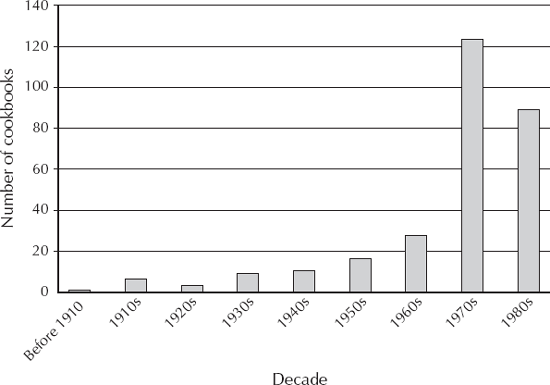

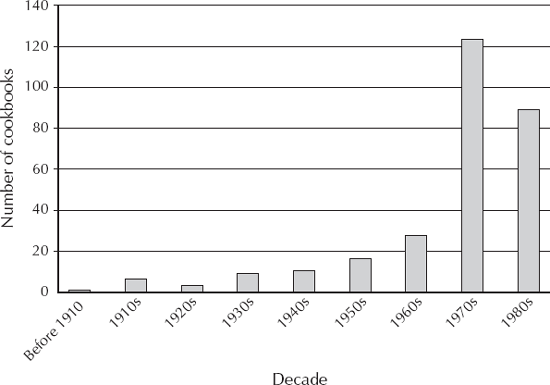

Those early cookbook writers were keenly aware that Chinese-food cookbook writing was closely linked to the rising popularity of the Chinese restaurant. Jessie Louise Nolton, the author of America’s first Chinese-food cookbook, knew that “the favorite dishes of the Orient are rapidly becoming favorite dishes of the Occident.”44 In their Chinese–Japanese Cook Book (1914), Sara Bosse and Onoto Watanna remarked: “Chinese cooking in recent years has become very popular in America.”45 As we can see in figure 6, Chinese-cooking cookbook publication started to pick up steam in the 1930s and 1940s, and accelerated in the postwar decades, accompanying and fueling the Chinese restaurant boom in the United States.

By 1985, when Chinese restaurants had already become the most dominant force in the “ethnic” dining industry, more than 280 Chinese-food cookbooks had been published in the United States. Besides the voluminous numbers, their prevalence is also evidenced by the wide participation in writing about Chinese cooking. Authors of Chinese recipe books during this period include Chinese and non-Chinese men and women. Among the non-Chinese are well-known authors like the Nobel Prize–winning novelist Pearl Buck, who grew up in China, and Emily Hahn, a prolific writer and high-profile figure in the Chinese-U.S. world before the end of World War II.46 In the postwar years, Chinese cookery publishing was also associated with the names of heavyweights in mainstream American gastronomy like James Beard, dubbed by the New York Times “the dean of American cookery” in 1954, and the celebrated food critic and author Craig Claiborne.47 Major companies that developed prepackaged Chinese food, such as Chun King and La Choy, issued handbooks on Chinese cookery.48 Even Betty Crocker—a fictitious and iconic personality in food consumption and a long-standing symbol of America’s racial identity—had a Chinese-food cookbook published under her name.49

FIGURE 6 The number of Chinese-food cookbooks published in the United States, pre-1910–1985. (Jacqueline M. Newman, Chinese Cookbooks: An Annotated English Language Compendium/Bibliography [New York: Garland, 1987]; Yong Chen, Chinese-food cookbook collection)

CULINARY AMBASSADORS

Studying Chinese-food cookbooks is paramount to understanding the role that individual Chinese Americans played in popularizing Chinese cooking because about 70 percent of these books were written by Chinese Americans.50 Writers of Chinese-food cookbooks were culinary ambassadors: in bringing Chinese food to mainstream America, they played roles that were quite different from those of Chinese restaurant owners. First of all, while the latter’s motivation was largely economic, the former’s function was primarily cultural. Second, while the restaurants’ clientele always included Chinese diners, the cookbooks’ audience in the early decades existed for the most part outside the Chinese community, which remained small and foreign born.51 Chinese American authors, in particular, made a conscious attempt to address non-Chinese readers. Buwei Yang Chao remarked: “If you live far from Chinese restaurants, roasting your own Peking duck can be very rewarding.”52 Third, while the restaurants remained largely a phenomenon in urban public consumption, the cookbooks promised to carry knowledge of Chinese food to private spaces of readers and remote areas without Chinese restaurants.

Finally, the cookbooks presented more systematic and comprehensive knowledge of Chinese cooking than did the restaurants. Chinese restaurants had to accommodate the preferences of their consumers, especially the repeat customers. Those located outside metropolitan areas, in particular, served a rather predictable set of dishes. Cookbook writers, by comparison, had more autonomy over the content of their work, with the freedom to elaborate on a wide range of dishes and pertinent topics. Some, for example, included discussions of both the cooking and the eating of Chinese food, treating “the arts of eating and cooking as a single subject, each supporting the other,” as two Chinese cookbook authors put it.53 And many provided broader historical contexts of Chinese cuisine.

Nevertheless, Chinese-food cookbooks were by no means isolated from public Chinese-food consumption but were closely related to its trends. Popular dishes like chop suey featured prominently in major Chinese-food cookbooks in the first three decades, when chop suey became the synonym of Chinese food in the restaurant market: the Pacific Trading Company of Chicago even titled its cookbook Mandarin Chop Suey Cook Book (1928).54 Besides eight chop suey dishes, it includes other trendy dishes such as chow mein and egg foo young.

Sometimes cookbook writers anticipated and effected changes in Chinese-food consumption. In the 1940s and 1950s, while chop suey remained quite popular in Chinese restaurants and can be found in writings about Chinese food, some Chinese-cookbook authors started to distance themselves from this iconic food.55 In Buwei Yang Chao’s How to Cook and Eat in Chinese (1945), the words “chop suey” disappeared and were replaced by “stir” or “stir-fry.” Hu Shih, the “father of the Chinese literary renaissance” and one of the most influential minds of twentieth-century China, credited her as the person to have coined this new culinary phrase in English. The term “stir-fry” thus became the accepted terminology in both Chinese restaurants and cookbooks.

By the late 1950s, Chinese-food writers like Calvin Lee, a third-generation Chinese American owner of a long-standing Chinese restaurant in New York, referred to the “Chop Suey Era” as belonging to the past.56 And indeed, the Chinese restaurant industry was about to enter a new phase.

Corresponding to the shifts in the market place, Chinese-food writers updated their work, adding new recipes. Changes in duck recipes in Chao’s How to Cook and Eat in Chinese are a case in point: the second edition (1956) includes a new recipe for “roast duck (Chinese style)”; and the second edition, revised (1968), added more elaborate recipes for “roast duck (Peking style)” and “Szechwan duck.” All three were absent in the book’s original edition (1945).57

The word “Szechwan” is an old-style romanization of Sichuan, a province in the western hinterland of China, known for its highly distinctive (and spicy) style of cooking. Chao’s use of the word indicates the emerging attention in the late 1960s to regional variations in what had previously been generalized under the single category of “Chinese food.” This new trend is clearly seen in Emily Hahn’s The Cooking of China (1968), which elaborates on the culinary regions in China. In the opening chapter “An Ancient and Honorable Art,” she writes: “Some Chinese still refer to the five early cooking styles of Peking, Honan, Szechwan, Canton and Fukien, but today it is more realistic to speak in terms of four more general schools of cooking: northern (including Peking, Shantung and Honan); coastal (including Shanghai, Hangchow, Soochow and Yangchow); inland (Szechwan and Hunan); and southern (the area around Canton).”58 The chapter also discusses Chinese geography and history, injecting a lucid lesson in culture into the cookbook.

The 1970s witnessed an explosion in publications on Chinese cooking, when more than 120 new titles appeared. This increase coincided with important historical developments taking place at the time. Most significant was the postwar growth of the Chinese population in the United States, which grew from 150,000 in 1950 to more than 800,000 in 1980. Much of that growth is a result of increased immigration. In the 1960s, 34,764 Chinese immigrants came to the United States, representing a record number since the 1880s and an almost 300 percent jump from the previous decade.59 Unlike the prewar immigrants, who were primarily Cantonese, the new arrivals came from more varied geographical backgrounds. They not only broadened the customer base and labor force of the Chinese restaurant industry but also brought culinary knowledge from regions other than Guangdong. Another notable event was President Richard Nixon’s historic visit to China in 1972. The image of Nixon using chopsticks and eating Chinese food on national television undoubtedly augmented the public interest in Chinese food. It gave a strong boost to the upward trend in Chinese-food cookbook publishing already under way before his trip.60

The new cookbook titles significantly expanded the knowledge about Chinese food available to American readers. Several themes—including regional traditions in Chinese cooking, health, and convenience—now received more extensive attention. The 534 pages of An Encyclopedia of Chinese Food and Cooking (1970) cover broad topics relevant to Chinese food. Besides recipes, it includes discussions of regional Chinese cooking, a section on instant dishes, and extensive information on diabetic and ulcer diets as well as recipes.61 While some authors introduced several regional traditions, other focused on specific regions.62 Cookbook authors also deepened American readers’ awareness of Cantonese cooking by introducing dim sum, which Chao had spelled as timsam, a small-bite type of snack food served in large varieties with tea.63 The regions that received particular coverage included Beijing, Hunan, and Sichuan, and dishes from these regions began to appear with increasing frequency on restaurant menus.64 During the 1970s, cookbook writers also made a conscious effort to address the mounting health concerns of American consumers by offering tips on vegetarian and healthful cooking, reflecting and reinforcing the image of Chinese food as a wholesome cuisine.65 Another theme that several authors highlighted is the simplicity or convenience of Chinese cooking.66

Marbled (Tea) Eggs

Many cookbook writers, ranging from the Qing epicurean Yuan Mei to the twentieth-century Chinese American writer Buwei Yang Chao, have offered recipes for this simple dish, which shows that good food does not have to be fancy or difficult.

12 eggs

½ cup light soy sauce

1 tsp dark soy sauce

3 tbsp tea (black, oolong, or pu er) or 3 tea bags

1 tsp cinnamon powder

2 star anise

6 small pieces dried tangerine peel

dash of black pepper

Wash the eggs thoroughly. Immerse them in cold water in a pot. Bring to a boil for 2 minutes. Turn to low heat and simmer for 7 minutes, turning the eggs a few times. Then promptly cool the eggs in cold water. Use a dull object (like the back of a spoon) to gently tab the eggs to create cracks on the surface. Put the eggs back in water together with the other ingredients. Bring to a boil and then simmer for 1 hour.

DEFINING CHINESE FOOD AND EXPRESSING THE SELF

Signifying a dialogue between two cultures, writing about Chinese food was shaped by both Chinese and American cultural influences. The English-language Chinese-food cookbook was wrought as a separate genre by American influence as its initial model came from Anglo-American authors. America’s first Chinese-language cookbook, Cui Tongyue’s Hua Ying Chu Shu Da Quan (Chinese–English Comprehensive Cookbook, 1910), contained only Western recipes translated from English-language sources.67 Such direct translations of English-language cookbooks introduced American cookbook-writing conventions to Chinese readers. Moreover, the first Chinese-food cookbook published in the United States was written by a non-Chinese author, who worked for the Inter-Ocean, a newspaper published in Chicago: Jessie Louise Nolton’s Chinese Cookery in the Home Kitchen (1911).68 In this as well as subsequent cookbooks, American conventions in recipe format became a model for Chinese-food writers, of which some of them were conscious. M. Sing Au noted in 1936 that Chinese chefs’ expertise had to be rendered understandable for non-Chinese readers: “Chinese chefs rely on judgment for their measurements. They have no thermometer to tell degrees of heat, no cup or spoon to measure quantity by, no clock to tell time. Their directions, translated as accurately as possible, are herein set down simply enough for anybody to follow, it is hoped.”69 It is interesting to note, however, that none of the early Chinese-food cookbooks were direct English translations of existing Chinese-language cookbooks.

A more important American influence came from the nature of the readers. As mentioned earlier, Chinese-food writers were writing largely for non-Chinese whose cultural backgrounds compelled these writers to articulate and define Chinese cuisine.

In so doing, Chinese-food cookbook authors greatly advanced Chinese food as a system of cooking while pushing it across cultural boundaries. They felt an urgent need to define Chinese food also because few had clearly or comprehensively done so before. In the foreword to Chinese Gastronomy (a cookbook written by his wife and third daughter), Lin Yutang remarked in 1969: “There has been a flood of Chinese cookery books. But there has never been a Chinese Savarin in English.”70 The Chinese-food Brillat-Savarins had a vast vacuum of knowledge to fill, and they had to convince readers that Chinese food was not only desirable to eat but also manageable to cook. The task of articulating and advancing Chinese food fell mostly on the shoulders of Chinese Americans, who wrote most of the Chinese-food cookbooks during this period and provided the first elaborations on Chinese food as a cuisine.

If the model for recipe presentation came from American cookbook writing, the inspiration for Chinese-food cookbooks came from Chinese traditions, which offered a time-honored reservoir of culinary knowledge and experiences; it also afforded Chinese American authors expert authority.

From the very beginning, these authors constantly invoked Chinese history and culture. In The Chinese Cook Book (1917), one of the first books on Chinese cooking written by a Chinese, Shiu Wong Chan credited “the Emperor of Pow Hay Se [Pao Xi Shi] in the year 3000 B.C.” as the inventor of the “Chinese method of cooking.” If Pow Hay Se was unfamiliar to American readers, the next historical figure that Chan mentioned was no stranger.71 “Confucius,” he wrote, “taught how to eat scientifically. The proportion of meat should not be more than that of vegetable. There ought to be a little ginger in one’s food. Confucius would not eat anything which was not chopped properly.” Chan linked contemporary Chinese cooking to the great philosopher: “To-day, unconsciously, the Chinese people are obeying this law.”72 Wallace Yee Hong, another cookbook author, opened the introduction to his cookbook with a few made-up Confucius quotes, including one that sounds more Victorian than Confucian: “To win the heart of your husband—satisfy his stomach.”73 Lee Su Jan and his wife, May Lee, who taught Chinese cooking lessons in Seattle, also mentioned the legendary figure Fu Xi Shi/Pow Hay Se and acknowledged the impact of Daoism on Chinese cooking. But they traced Chinese food’s origin to Confucius. “It was Confucius,” they wrote, “who set the standard of culinary correctness and who regulated the customs and etiquette of the table.”74

Proud and elaborate reference to Chinese culture and history remained a common practice in Chinese-food cookbooks. In the beginning sections of Isabelle C. Chang’s cookbook, for instance, the author discussed topics like the Chinese calendar system, the Chinese kitchen god, a brief history of Chinese cooking, and Chinese pottery.75 She also provided an extensive list of recipes for various Chinese holidays and festivals. Such a practice increased Chinese Americans’ cultural authority and signaled their conscious effort to “change Western stereotypes of the Chinese as barbarians.”76

Chinese American writers consistently devoted much energy to delineating the distinctiveness of Chinese cuisine by clarifying its basics, including the methods of cooking, ingredients, sauces, utensils, and menu planning. A defining element of cuisines, cooking methods received extensive coverage. Chan’s cookbook includes the section “General Laws of Chinese Cooking,” where he stated: “There are three methods in Chinese cooking: steaming, frying, and boiling.”77 It was a conclusion accepted by others, such as Au, who wrote: “The three methods most commonly employed in Chinese cooking are: steaming, frying, and boiling.”78

In time, discussions of Chinese cooking methods became more extensive and more sophisticated. In 1945, Buwei Yang Chao devoted nine pages of her cookbook to the elaboration of twenty methods of cooking: boiling, steaming, roasting, red-cooking, clear-simmering, pot-stewing, stir-frying, deep-frying, shallow-frying, meeting, splashing, plunging, rinsing, cold-mixing, sizzle, salting, pickling, steeping, drying, and smoking.79 In addition, she offered lengthy discussions of chopsticks and other utensils, Chinese culinary terminology, and basic categories of ingredients, turning the cookbook into an encyclopedic volume on Chinese cookery. Furthermore, she summarized a conceptual foundation of the Chinese meal system as the dichotomy between fan, which is often construed as “rice” in the south, and tsai (cai) or “dishes.” This duality underlines a fundamental characteristic of China’s centuries-old starch-centered diet structure, in which starchy foods like rice constituted the main source of calories. That was “the opposite of the American eating system.”80 Nineteenth-century American visitors to southern China duly noticed the centrality of rice in the Chinese diet. Rice, Samuel Wells Williams wrote, “is emphatically the staff of life.”81 In another cookbook originally published five years after Chao’s, Doreen Yen Hung Feng identified the seven “most frequently used methods of cooking” in a lengthy chapter on the principal methods of Chinese cooking: chow (frying and braising), mun (fricasseeing), jing (steaming), hoong sieu (red-stewing), sieu (roasting, barbecuing, or grilling), ji’aah (deep-fat frying), and dunn (steaming and double-boiling).82 In the same chapter, she also offered detailed discussions of ingredients, utensils, and important concepts in Chinese cooking.

“What is Chinese food?” The cookbook writers Jonny Kan and his collaborator Charles L. Leong directly confronted that question.83 In an effort to answer and thus explain the differences between Chinese and American cooking, they covered topics like flavors, cooking and preparation methods and their regional variations, cooking and eating utensils, as well as sauces and other ingredients.

Hsiang-ju Lin and Tsuifeng Lin’s Chinese Gastronomy (1969) is a milestone in the articulation of Chinese cuisine. A must-read for anyone with serious interest in Chinese food, the book demonstrates and effectively utilizes the authors’ extraordinary culinary and historical knowledge. The book discusses the basic characteristics of Chinese food, including the criteria that the Chinese use for appreciating food in terms of flavor and texture as well as the cooking methods and ingredients used to achieve that desired flavor and texture. It also includes an entire chapter on China’s regional cooking.

Of particular importance is the chapter on China’s ancient cuisine, which constitutes a well-researched treatise on the historical evolution of Chinese cooking. In chronicling changes in cooking methods, utensils, and ingredients, the authors make in-depth references to ancient classics like the Book of Rites and the Shijing (Book of Poetry) as well as mentioning such noted literary figures as the famous Tang poet Du Fu and the Song poet and famous foodie Su Dongpo. The chapter also includes lengthy discussions of ancient Chinese cookbooks and food writers. One cookbook is Wu Shi Zhong Kui Lu (The Cookery of Manager’s Records of Ms. Wu), written in the Song dynasty (960–1279) by an author known to us only by the last name of Wu, whom many believe was a woman from Zhejiang Province.84 This was also one of the first Chinese cookbooks that include measurements; written in the vernacular, its recipes were for common dishes.85 Quite expectedly, Hsiang-ju Lin and Tsuifeng Lin also devoted considerable space to discuss “the great gourmet Yuan Mei.”86 Hsiang-ju even tested every recipe in the cookbook of ancient China’s culinary giant.

The two authors’ inclusion of extensive historical discussions signifies a comprehensive and ambitious attempt to understand and present Chinese cooking as a process. In reference to the classical period, they wrote: “The ancient cuisine was not distinguishably ‘Chinese.’ … By the eighteenth century, Chinese gastronomy had already developed its glories and its pitfalls, had encompassed the tastes of the food snobs, the gourmet, the peasant and the artist. It is very much like that now.”87

Such a blending of history and culture into food writing was a strategy adopted by other authors, including non-Chinese writers such as Emily Hahn and Gloria Bley Miller.88 Representing Chinese food as a sophisticated and rich culinary system developed over the centuries, and praising it as art—a word that Chinese-food authors first adopted and frequently used in characterizing Chinese food—undoubtedly helped to promote Chinese food.89 Grace Zia Chu wrote in 1962 that “the art of Chinese cooking was passed down from generation to generation. … The techniques of this art,” she continued, “were developed and refined over thousands of years.”90 Such a characterization of Chinese food was especially meaningful for Chinese Americans as it reinforced their authority and the cultural authenticity of their work. Furthermore, the positive representation of Chinese food and culture was an affirmation and a proclamation of this identity. In The Classic Chinese Cook Book (1976), Mai Leung acknowledged an intellectual and cultural debt to the people of China, calling them “my people”: “To the people and culture of China, I acknowledge my enduring indebtedness. The collective experience of my people has been my teacher and my benefactor. I had the good fortune to be born among them, to participate in their learning and experience.”91

The cookbooks written by Chinese Americans also reveal the importance of Chinese-food writing as a vehicle for empowerment. For these authors, its meaning extended beyond the realm of gastronomy: it gave Chinese Americans the most significant stage on which to address mainstream audiences. A few Chinese Americans, such as the food promoter and civil-rights fighter Wong Chin Foo and the newspaper editor Ng Poon Chew, occasionally spoke to non-Chinese audiences in speeches or articles in the mainstream print media. But these represented sporadic occurrences. In general, though, Chinese Americans kept silent in public life.

Nonetheless, through cookbook writing Chinese authors created a highly visible and steady venue of public communication that they could claim as their own. In writing about their food, they spoke not as marginalized minorities or victims of discrimination but as experts and teachers of the art of Chinese cuisine, diverging from the racial power structure that prevailed in the larger society.

What is more, cookbook writing gave Chinese American women a particularly meaningful and prominent forum. About three-quarters of the Chinese-food cookbooks published in the first eight decades of the twentieth century were written by women.92 In public life in the early years, the voices of Chinese American women were seldom heard and their physical presence was rarely seen. This is in part because the number of Chinese women was extremely small in those years. Moreover, they faced not only racial discrimination in American society but also gender prejudice within the Chinese American community. They were even discouraged from going to Chinese restaurants in the early years.

For Chinese American authors, Chinese-food cookbook writing also constituted a form of self-expression. Beginning in the 1940s, Chinese American female cookbook writers outnumbered their male counterparts, and in their writing, the personal voices of Chinese cookbook authors became even more vocal over time. Buwei Yang Chao, for instance, noted how she learned to cook with “an open mind and an open mouth.”93 She also talked about her family’s involvement in the production of her book. She mentioned her daughter’s contribution in rendering the text into English and, in a humorous tone, her husband’s role as a taster and critic. In Mary Sia’s Chinese Cookbook (1956), Sia discussed her mother’s zest for living and hospitality as the inspiration for her own interest in “the art of Chinese cooking.”94 For Hsiang-ju Lin and Tsuifeng Lin, writing a cookbook was also a family affair—a mother–daughter collaboration. As husband and father, Lin Yutang wrote an engaging foreword to the book and also served as a food tester.

The inclusion of family and personal experiences like these is extremely important, illustrating that cookbook writing is in essence a highly personal endeavor. As such, Chinese-food cookbooks did not have the same direct and extensive economic connection to the Chinese community at large as did the Chinese restaurants. Except for those published within a Chinese community, the cookbooks did not play the same role in forging or reinforcing a collective cultural identity, as did Chinese restaurants for Chinese America or Indian cookbooks for India. But this does not diminish the extraordinarily broad social importance of the Chinese-food cookbooks. These publications gave definitive voice to Chinese Americans, who otherwise remained as statistics in government documents or as stereotyped beings in the mass media. These cookbooks functioned as an effective tool in the Chinese struggle against racial prejudice. Cookbooks help us better understand the historic rise of Chinese food in the United States. Finally, they stand as a vivid reminder that the historical forces that shaped American Chinese food and our world are intimately and inseparably linked to our life as individuals.