This book began with my first arrival in the New World from China in 1985. Now I fast-forward to 1997, when I returned to my homeland after a twelve-year odyssey in the United States. Reminding us that “home” helps individuals relate to the larger world, the scholar Aviezer Tucker writes: “Home is the reflection of our subjectivity in the world.”1 Indeed, my long-awaited homecoming not only brought back previous memories but also was a moment of new revelations about the meanings of Chinese food, the “home” that food signified, and the geo-economic order in the modern Pacific world that predicated America’s Chinese cuisine as well as my voyage to the United States.

In characterizing my New World journey, I have borrowed the title word of Homer’s epic. Food has served as a vital signifier of identity in my American journey, as it did in the adventurous travels of Odysseus, the hero of Homer’s Odyssey. He referred to unfamiliar people, such as the “Lotus-Eaters,” “who live on a flowering food,” in terms of their food habits.2 Moreover, Odysseus harbored an uncompromising desire to return to his beloved home on Ithaka, an island off the coast of Greece. Similarly, when I left China for the New World or, more precisely, the upstate New York college town of Ithaca, I had only one intention: to get my doctorate in American history at Cornell University and return home.

Remembrance of home is a universally perennial motif in the experiences of immigrants and travelers. Ah Quin dreamed about his parents back in Kaiping County.3 He never returned to settle in China before his sudden death in San Diego in 1914. Many early Chinese immigrants also dreamed of returning home to China. Even those who could not afford to realize this dream in their lifetime still wished to be buried in their native place, which is why shipping the dead back to China remained an important task of the Chinese American community for decades. An old Chinese saying poetically conveys this desire: “Falling leaves return to their roots.”

In the minds of these early Chinese immigrants and others, home represented not only a physical location but the way things used to be in the pre-emigration world as well. While living in the United States, therefore, Chinese Americans also tried to re-create a physical and cultural space that they could call home. In doing so, they formed Chinatowns, transplanted and supported their cuisine, articulated the meaning of Chinese food, and affirmed their identity as Chinese Americans.

Finally returning to his homeland after being away for twenty years, Odysseus reclaimed his home when he destroyed the intruders. But coming back to my native land, “home” became more elusive than ever before. No sooner had I stepped back on Chinese soil than I realized that “you can’t go home again,” the conclusion also reached by George Webber, the protagonist in Thomas Wolfe’s novel.4

People have long associated the concept of home with a physical locus. As John Hollander notes, the English word “home” is derived from the Anglo-Saxon ham, meaning “village,” “town,” or “estate.”5 Many early Chinese immigrants kept almost photographic memories of scenes around the village, where their ancestral home resided, such as the small creek with water flowing in a leisurely way and shepherd boys singing joyfully on their way home.6 Odysseus unwaveringly remembered his physical destination during his two decades of wandering, and even Wolfe’s Webber had a hometown to return to. But home for me no longer meant a particular place. I did not return to the home of my childhood. My retired parents had moved from my native town to Wuhan, the capital of Hubei Province. Located in one of the recently built apartment buildings in Wuchang District, their two-bedroom unit hardly fit the image of home that I had longed for.

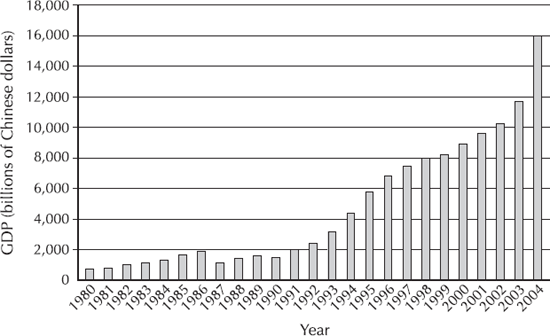

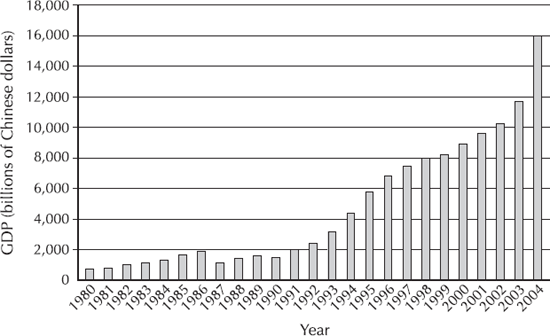

The country itself was also no longer the homeland of my youth. China had embarked on an unprecedented economic metamorphosis that promised to shatter the geo-economic conditions of our world. In a book published in 2005, Ted C. Fishman captures the astonishing pace and depth of the economic change that was under way in 1997: “No country has ever before made a better run at climbing every step of economic development all at once. … No country shocks the global economic hierarchy like China.”7 Figure 7 shows the magnitude of this historic transformation of the Chinese economy, which would become the second largest in the world by 2011.

FIGURE 7 The growth of the gross domestic product of China, 1980–2004. (National Bureau of Statistics of China)

China’s economic takeoff was fast narrowing its economic gap with the United States, a gap that has been a fundamental feature in the relationship between the two countries, playing an important role in shaping the character of American Chinese food. In the cities I visited in 1997 during my trip, the landscape was way beyond my recognition. As an indication of the drastic physical transformation under way, one-fifth of all the world’s high-rise construction cranes in operation were now located in Greater Shanghai.8

Aside from a physical place, we also associate home with food. People often use the word “homemade” to describe the food that we cherish and find familiar. This association between food and home is coded in the Chinese character for “home,”  (jid). The upper part of the word,

(jid). The upper part of the word,  , represents a house, and the lower part,

, represents a house, and the lower part,  , a pig.9 In other words, home is where we expect to find nourishing, comforting, and familiar food.

, a pig.9 In other words, home is where we expect to find nourishing, comforting, and familiar food.

Strolling on the streets of China’s fast-changing cities, however, I could not even smell the once homey aroma of food. New eateries, including KFC and McDonald’s, and often more upscale restaurants had replaced old food places. Back in 1985, there was no American fast food in China’s food market. To get a hamburger in Beijing at that time, one had to go to the few exclusive hotels that were off-limits to ordinary Chinese, and it cost my American friends Bruce and Sandra 8 yuan, or about one-third of a common worker’s monthly income, to buy my first American hamburger in the Great Wall Hotel. The rapidly expanding presence of the Golden Arches and Colonel Sanders in urban China now epitomizes a country in drastic metamorphosis.

American fast food’s swift advance in China stands in sharp contrast to the development of Chinese food in America, which traveled on a long and winding road to mainstream America and consisted largely of small family operations. Backed by big capital, the Big Mac, by comparison, was an instant, spectacular success. The opening of China’s first McDonald’s in Beijing on April 23, 1992, shattered the Moscow opening-day record, attracting some 40,000 Chinese customers to the 28,000-square-foot restaurant, which had twenty-nine cashregister stations to handle the flow of customers.

Chinese restaurants rose to serve cheap food largely to underprivileged American consumers. Coming to China a century later, however, American fast food became an important part of the lifestyle of young and affluent consumers. In 1994, according to the anthropologist Yunxiang Yan, “a dinner at McDonald’s for a family of three normally cost one-sixth of a worker’s monthly salary.”10 In 2004, a relative of mine, who worked at a local bank in Wuhan, spent almost one-fifth of her monthly salary to take both our families to a KFC. In 1987, KFC was the first American fast-food company to arrive in China, and it has been the most successful.11 The number of its stores broke the one thousand mark in 2004 and exceeded four thousand in 2012, almost three times the number of McDonald’s outlets in the country, making KFC the largest restaurant franchise in China. When the four thousandth KFC store opened its doors in the coastal city of Dalian on September 25, 2012, the restaurant was serving at least 700,000 Chinese customers daily, or more than 250 million a year.

As in the case of American Chinese food, the spread of American fast food in China is also a socioeconomic, rather than a gastronomic, story. In other words, its success bespeaks the global dominance of America as an empire of mass consumption more than the supremacy of its food. Since 1997, the power of the American empire of mass consumption has been ever more evident in China, where the desire to live like Americans continues to expand. Even the Chinese premier wanted every Chinese to be able to have half a quart of milk every day.12 At the same time, the consumption appetites of the more affluent consumers have made China’s real estate red hot and turned the country into the world’s largest automobile market in 2009. In terms of consumer desires and physical appearance, China increasingly looks more like America than the country where I grew up.

Everywhere I went in China in 1997 and in subsequent years, family and friends showered me with touching affection and generous hospitality. Many were eager to show me the good and real food of China. The food I tasted in glitzy restaurants, in little mom-and-pop places on crowded streets, or at the chaotic and dirty da pai dang (cooked-food stalls) opened my eyes to the diverse and dynamic world of Chinese cooking that I had not fully known before. It also reveals the complexities of questions about culinary authenticity, prompting me to wonder: Which is more authentic, the food of China in 1985 or that in 1997 and after?

Odysseus’s odyssey concluded with his eventual homecoming, but mine has continued. Coming home to China, I realized that I could no longer return to the native land of my childhood, and I have become a temporary visitor and, quite often, a stranger. For all the years in the United States, I had been a Chinese in the minds of myself and others, but old Chinese friends in China saw and treated me more as an American than as a Chinese.

Where is home? I asked myself over and over. That question has attracted much scholarly interest in recent years. As Shelley Mallett points out, “There has been a proliferation of writing on the meaning of home” in a multitude of disciplines.13 For me, though, it is not just an academic question but also an existential one about my selfhood in a fast-changing world, which sometimes makes me wonder which has changed more, China or myself.

Unlike Odysseus, who overcame many ordeals and temptations in his steadfast resolve to return to his home, I have eaten and have learned to enjoy many of the different cuisines that America has to offer, such as Indian, Japanese, French, Thai, Greek, Mexican, Korean, and Vietnamese. I have acquired a house and a job in southern California, where the climate turns people into lotus eaters, as the British thinker Bertrand Russell was once told.14 As Odysseus knew, those who had eaten this “honey-sweet fruit” would forget their homes and want to stay with “the lotus-eating people.”

Many early Chinese immigrants kept strong memories of China as their homeland but not just because they continued to uphold their traditional diet. There was another reason: the anti-Chinese racism they suffered in the United States, which repeatedly banned the entry of the Chinese, took away the rights of those visiting China to return to America, denied Chinese immigrants the right to become citizens, and even prohibited them to own real estate or marry a white person. In reference to such racial prejudice, Lee Chew remarked more than a century ago: “Under the circumstances, how can I call this my home, and how can any one blame me if I take my money and go back to my village in China?”15

The transformation of American society since then has fundamentally altered the meaning of being American. I have never had to face the same kind of racism that early Chinese Americans like Lee Chew did. Spending a majority of my half-century-long journey on earth in the United States, I have come to know the gastronomic landscape in American cities like Irvine, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York better than in Beijing, Shanghai, Nanjing, and Wuhan. Important changes in the socioeconomic conditions within China and America and in the U.S.-China equation during the past quarter-century have quietly but drastically shifted the meaning of home for Chinese Americans.

These changes have also broadened the meaning of Chinese food in China. A dazzling array of diverse regional and local foods from different provinces as well as Taiwan, Hong Kong, and ethnic Chinese communities in Southeast Asia has become a constant feature of the Chinese-food markets in major cities. Even American fast food in China has started to offer Chinese breakfast and lunch meals with increasing zest. Around 2004, the two giants, McDonald’s and KFC, started a fierce war, each offering different Chinese breakfast items. Now, even traditional items like KFC’s chicken popcorn sometimes tastes different from its version in America, as my two young sons found out in Wuhan in 2004—“It is so spicy!” they screamed. In January 2013, Yum! Brands—a restaurant company whose brands are KFC, Taco Bell, and Pizza Hut—received the Chinese government’s permission to acquire, for $566 million, Little Sheep, a Mongolian hot-pot restaurant chain that first started in Inner Mongolia in 1999.16

As an illustration of how complex questions about the meaning of Chinese food have become, Chinese Americans have opened two restaurant franchises in China, selling food that is apparently Chinese but claiming it to be American in origin. Both offer “California beef noodles” (jiazhou niu rou mian). The founder of one of them, Wu Jinghong, started China’s earliest California Beef Noodle King U.S.A. restaurant in 1986. By 2006, the franchise had more than three hundred stores nationwide. In spite of its name, this is, in reality, a brand made in China, not California or anywhere else in the United States. She did not even register the company in the United States until 1996, as she admitted to a reporter of Beijing Chen Bao (Beijing Morning News) in 2004.17 Another California beef noodle restaurant franchise was started in 1987 by Li Beiqi, a China-born, Taiwan-educated Chinese immigrant. In 2008, Li changed the name of the more than four hundred restaurants from California Beef Noodle King to Mr. Lee. But as I have found out during my visits to several Mr. Lee outlets in recent years, reference to California Beef Noodle King remains visible in various places, including on its napkins. During a conversation with me in 2010, a customer in a Mr. Lee restaurant near Peking University was surprised to learn that the food was not American.

Changes in the China-U.S. Pacific world are also exerting a transformative impact on the Chinese-food industry in the United States. New waves of immigrants from far more diverse geographical regions in both China and the Chinese diaspora have added an extensive array of new dishes to the menus of Chinese restaurants. While some traditional American Chinese foods like chow mein and egg foo young have stayed quite noticeable, chop suey has long lost its prominence, eclipsed by Kung Pao, Sichuan, Hunan, and moo shu dishes. A few new dishes—most notably General Tso’s chicken, which was adapted from a Hunan-style dish by a Taiwanese immigrant named Peng Chang-kuei—have evolved in the United States.18 A growing number of Chinese restaurants, especially those in non-Chinese neighborhoods, offer dishes from non-Chinese cuisines, such as Japanese, Thai, Korean, and Malaysian. Many all-you-can-eat Chinese buffets, which have mushroomed across the nation in recent years, also prominently feature sushi, Thai-style noodles, and American desserts. Recent immigrants, especially ethnic Chinese from Cambodia, have opened restaurants that offer both Chinese food and donuts in California, where immigrants from Cambodia had owned 80 percent of the independent donut shops by the early twentieth century.19 In such establishments as Jolly Chan’s Chinese Food & Donuts in San Francisco, Chinese foods like orange chicken and fried rice with a “rainbow of donuts” combine to make a statement of cultural hybridity.20

Established food companies in mainland China as well as Taiwan, such as the legendary restaurant group Quanjude Roast Duck (famous for its Peking duck), have opened branches in the United States. Compared with the early Chinese-food establishments, which remained small operations, these new enterprises have far more resources and expertise, and can expand much more quickly. Little Sheep now operates in eleven cities in the United States, including Dallas, Irvine, New York, San Diego, San Gabriel, and San Mateo. The Little Sheep in San Mateo has already been recognized by CNN as one of the fifty best Chinese restaurants in the United States.21

More important, a continually improving Chinese economy will further shorten the economic distance between the United States and China. In doing so, it will significantly change the image and reality of the Chinese as a source of cheap labor. Such a change, in turn, will alter the century-long trajectory of American Chinese restaurants which have relied on Chinese labor.

Yields 16 cakes

It is time for dessert. Like our personal experiences, the development of foods, such as moon cakes, is also entangled with historical currents, as I have shown in chapter 7.

FILLING

8 pkg Green Max (Ma Yu Shan) Black Sesame Cereal

1 cup ground black sesame (or ground almond)

1¼ cup powdered sugar

¾ cup multigrain baking and pancake mix

½ cup nuts: pine nuts, walnuts, or pecans

1½ stick butter, at room temperature

CRUST

3¾ cups flour

1 tsp salt

2 tbsp sugar

14 tbsp shortening

11 oz heavy cream

For the filling, put the ingredients in a bowl. Use a pastry blender or fork to cut the butter into small pieces or until crumbled. Mix the ingredients thoroughly. Divide into 16 portions. Press and make 16 balls.

For the crust, place the flour, salt, sugar, and shortening in a bowl. Use a pastry blender or fork to cut the shortening into small pieces. Pour in the heavy cream and make a dough. Add extra heavy cream if needed. Divide into 16 pieces.

Roll out the dough and wrap the filling inside each. Lightly flatten the cake. Refrigerate for 30 minutes. Bake at 350°F for 30 minutes.

Set off by the overwhelmingly foreign environment that I entered more a quarter-century ago, my longing for things palatable to eat was the genesis of this book. The search for Chinese food has led me to towns and cities across the nation. It eventually brought me to California, home to America’s first Chinatowns, and later all the way back to China. It was also a search for “home” in the fast-changing and globalizing world. But the exploration has also spawned new questions, including: Why there are so many Chinese restaurants in the United States? People in China and America have grappled with that question for more than a century. The ultimate answer lies not in the realm of gastronomy but in the geo-economic context in modern history, in which the United States has become a dominant power with incredible material abundance and China remained a land of scarcity and supplier of cheap labor. This context explains the exodus of Chinese immigrant laborers, who satisfied the budding consumption empire’s needs—first in private kitchens and laundries, and later in affordable and convenient Chinese restaurants. The labor of the Chinese as well as other minorities and immigrants has helped America maintain its attraction as a land of material abundance.

The world order of the past two centuries is now seriously challenged in the Pacific region. When Americans can no longer get a Chinese lunch special for as little as the price for a Starbucks coffee, when customers no longer expect the entire Peking duck for less than $30, and when opera-goers regularly dine in a Chinese restaurant before going to a theater for Puccini, then a new geo-economic order will be just around the corner. Then, perhaps, I will finally find the home that I have been searching for. Then there will no longer be the American Chinese food as we know it.

(jid). The upper part of the word,

(jid). The upper part of the word,  , represents a house, and the lower part,

, represents a house, and the lower part,  , a pig.9 In other words, home is where we expect to find nourishing, comforting, and familiar food.

, a pig.9 In other words, home is where we expect to find nourishing, comforting, and familiar food.