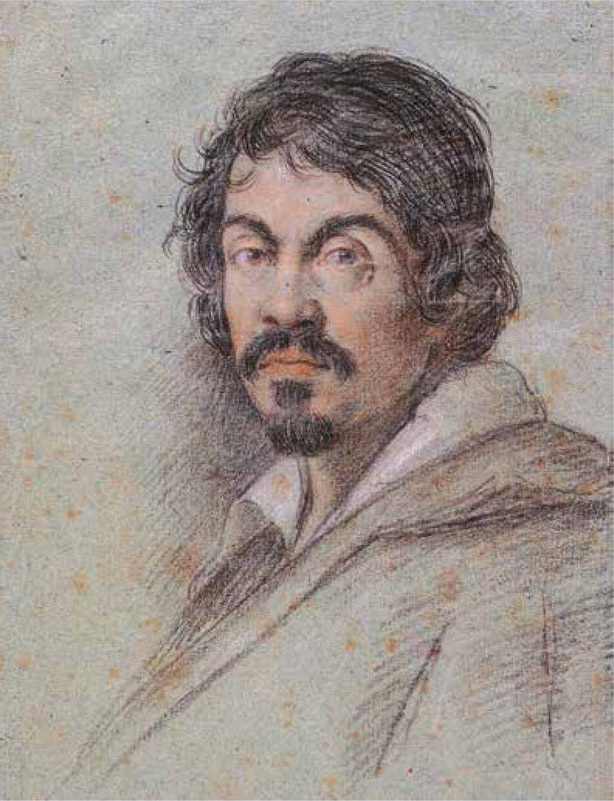

CARAVAGGIO

Figure 2.1. A drawing of Caravaggio, Ottavio Leoni, circa 1621. Biblioteca Marucelliana, Florence.

By Ottavio Leoni–milano.it, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=331612

Figure 2.2. The Beheading of St. John the Baptist, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1608. St. John’s Co-Cathedral, Malta.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Beheading_of_Saint_John-Caravaggio_(1608).jpg

Caravaggio

On a crisp and cloudless evening in late May of 1606, Ranuccio Tomassoni lay bleeding on a tennis court in Rome, the victim of a failed attempt by his dueling opponent to castrate him. Tomassoni was a scoundrel and a cad to be sure. He was a gang member, a pimp, and a bar brawler. What he was not was a great artist. That honor belonged to the man looking down upon him as he slowly bled to death. His assailant, Michelangelo Merisi, was known then as we know him now, as the great Baroque artist, Caravaggio! The details of the duel between Caravaggio and Tomassoni are somewhat contested, as the seconds on hand all told fabrications of the event to spare themselves from the consequences of having participated in what was illegal duelling.1 After all, even in early seventeenth-century Rome, murder was considered to be bad form. Caravaggio was forced to flee the scene and then the city where he had held incredible fame. He was the painter of Rome at the turn of the century, in continual demand to produce works both for the church and wealthy patrons. But his brilliance as an artist had been eclipsed once again by the darkness of his odious behavior. The law would be after him, and no doubt, Tomassoni’s gang as well.

It was time to go.

Caravaggio’s Life and Times

Chiaroscuro

Chiaroscuro is an artistic technique that involves sharp contrast between light and dark in order to create a dramatic effect. The word basically means “light and dark,” with chiaro meaning clear or light, and oscuro meaning obscure or dark. (Note that in Italian, the letter I often appears where there would be an L in English, as in piazza in Italian being plaza in English.)

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571 to 1610) was born into the upper middle class in the town of Caravaggio, near Milan, but did not enjoy life in that status for very long. His father and grandfather died within hours of each other from the plague when he was six years old, and his mother died when he was eighteen.2 Deciding he wanted to be an artist, at age thirteen he became an apprentice to Simone Peterzano and trained with him for four years, not unusual for aspiring artists. Similarities in style between Peterzano and Caravaggio are easy to see.

He completed his apprenticeship with Peterzano in Milan, and then struck out on his own. In some fashion, which isn’t entirely clear, striking out included spending a year in prison. It’s not certain what he did, but it appears to have involved people being stabbed and slashed (perhaps a police officer), prostitutes, and refusing to cooperate with the authorities. Kids!

FROM MILAN TO ROME: FAME, FORTUNE, AND FOLLY

Extracurricular activity in Milan left Caravaggio penniless and deciding to seek greener pastures in the Big City, in this case, Rome. At the end of the sixteenth century, Rome was a city of extravagance and magnificence, dedicated to pleasure and lavish living. An orphan, a convict, and an immense talent, Caravaggio was all of twenty years old.

For several years, Caravaggio peddled his talents painting portraits for sale and working in various studios, gradually moving up the hierarchy of fame of the master who employed him. He ultimately decided he was tired of painting “flowers and fruits” (as he put it) for other artists, and began a career of his own.3 The Cardsharps (figure 2.3), painted when Caravaggio was only twenty-three years old, is one of his earliest complete works and provides an idea of his immense talent. It also suggests the nature of the activities he engaged in when not painting. The longer you look at this work, the more you see. That is a constant in art viewing.4 Caravaggio is telling a story here. The boy on the left is the mark, being worked over by another boy his age and a con man who is signaling to his accomplice. Notice that all six hands are visible in the painting. The mark’s hands are clean and soft; the accomplice’s hands are similar, but note the dirt under the fingernails. And the con man wears gloves with holes in them, pretending to be a dandy, but with a well-worn wardrobe. The con man and the accomplice each have a hand on the gaming table, and with the other hand they are cheating the mark.5 They are in charge here. The boy being cheated by the cardsharps bears a bit of a resemblance to Caravaggio himself, based on other works that are known to depict the artist as a youth.

Figure 2.3. The Cardsharps, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1594. Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cardsharps.jpg

Baroque

Baroque is a style of art (in painting, architecture, sculpture, and music) that followed the Renaissance and Mannerism. It featured dramatic scenes, deep color, strong facial expressions and often, movement in the characters depicted. Baroque painters include Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Reubens, and Velazquez. The Catholic Church endorsed this style as it provided a stark contrast to the simpler (plainer?) approach to life and art espoused by the Protestant Reformation.

As was the case throughout his career, the light of Caravaggio’s incandescence blinded the elite to its heat. Eventually, he was taken on by Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte, whose patronage gave him commissions and widespread visibility. He had graduated from painting fruit and decorations in the frescoes designed and executed by more famous artists to becoming the sought-after artist of Rome. His newfound fame as an artist, however, did not temper his temperament. There are reports in the popular press and court records of Caravaggio engaging in street brawls, attacking a waiter because he did not like the plate of artichokes he had ordered,6 and throwing stones at the house of his landlady while singing lewd songs because she had the audacity to want him to pay his rent. These were his evening activities; during the daytime hours, he was busy spreading the gospel through his artistic genius and courting the clergy and other clientele.

Oeuvre

Oeuvre is a word of French origin that means the body of work of an artist or composer. It is sometimes used to refer to a single or subset of work, but usually means the entire work of an artist.

If you look at Caravaggio’s oeuvre as a whole, you cannot help but notice that in a number of his works, especially in his early days, there are young males depicted in suggestive poses, with full lips and languid eyes looking out invitingly to the viewer. His painting Bacchus in 1595 (figure 2.4) is a good example of this. These works have led to speculation at various times (contemporaneous to Caravaggio’s time, as well in the 1960s and 1970s) that he was homosexual. Although recent scholarship casts doubt on that contention,7 he may well have slept with both women and men. Fortunately, we live in a time where being gay is less of an issue than it was for individuals living in the sixteenth century within the purview of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1532, the Catholic Church declared sodomy a crime punishable by death.

Figure 2.4. Bacchus, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1595. Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bacchus-Caravaggio_(1595).jpg

And so, what do we make of a number of paintings that Caravaggio produced that were at least highly suggestive? We will probably never know for certain, but a reasonable speculation was that these works were a way for Caravaggio to “push the envelope” of his work. For certain there would be an audience for them, and they would reinforce Caravaggio’s self-image as one not tethered by the laws or the moral strictures of the time. He was a rebel.

ONCE AGAIN FROM LIGHT TO DARK: THE DUEL

His activities in Rome came to a head in 1606. He was working on half a dozen different altarpieces and related paintings in churches in Rome at the height of his fame and prestige. At the same time, he was carousing and fighting in the taverns and brothels in the evenings. It was a full life. Part of that life involved his relationship with a courtesan named Fillide Melandroni, whom he painted a number of times. In figure 2.5, she is depicted as Mary Magdalene, who at the time, in Catholic circles, was considered to be a repentant sinner. The work is titled Martha and Mary Magdalene and portrays Mary as she “sees the light” and repents her sinful ways. Caravaggio also painted Fillide as Saint Catherine and as Judith methodically beheading Holofernes. She was reported to be a beauty but always appears a bit dour in Caravaggio’s renditions of her. Of course, if you are being depicted as beheading someone, or about to be beheaded yourself, perhaps a countenance somewhere between focused and grim is appropriate.

Figure 2.5. The Conversion of Mary Magdalene (Also: Martha and Mary Magdalene), Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1598. Detroit Institute of Arts.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Martha_and_Mary_Magdalene-Caravaggio_(c.1599).jpg

As a courtesan of the time, Fillide Melandroni would have had a pimp, and that pimp is reported to have been none other than Ranuccio Tomassoni, whom we left bleeding to death at the opening of the chapter. Caravaggio was no stranger to sword fighting and had been arrested for carrying a sword when he had no permit to do so. The duel was described in reports of the time as having been due to an argument over a bet on a tennis match. That seems a bit over the top, even for Caravaggio, and besides, who brings four seconds to a game of tennis? It turns out to be much more likely the case that Caravaggio and Tomassoni were at odds over Melandroni; exactly why is not known. An arranged duel—complete with seconds on each side who were known for being helpful in a fight, on a tennis court that would allow ample moves of swordsmanship and which was known for hosting duels—is a far more likely explanation. It is also speculated that once Tomassoni was down, Caravaggio attempted not to kill him but simply emasculate him, accidentally cutting his femoral artery in the process. Apparently a spada da lato (side sword popular at the time) is a bit more unwieldy than a palette knife.

Caravaggio was also wounded in the duel, receiving a serious gash to the head. But that was not his most pressing problem. He had killed a man in a duel, a man with political connections of his own. Caravaggio had to flee, and always a man of action, he wasted no time in doing so. There was no advantage to hang around to be arrested and brought to trial. Thus, he was tried and convicted in absentia. His punishment was permanent banishment from Rome, along with a bounty on his head. Literally, a bounty on his head. He could be killed by anyone, who could then receive a reward for simply bringing Caravaggio’s severed head back to the ministry in charge of such things.

Caravaggio escaped to Naples, which was part of Spain at the time. Naples was substantially larger than Rome, and while certainly Catholic, was much less under the influence of the Pope. In Naples, he worked quickly to reestablish his status. It was just the beginning of what was called the Golden Age of Naples; the port city was thriving. Caravaggio was well-received by the ruling class of Naples, and with tens of thousands of registered prostitutes, seedy taverns, and dangerous quarters, it was his kind of town.

FLEEING TO AND FROM MALTA

Caravaggio received several commissions in Naples, but was soon off to the island of Malta. He had connections in Malta and was attracted by the idea that he might become one of the Knights of Malta, who at the time ruled the island. The Knights of Malta were originally known as the Knights Hospitallers, and their order was dedicated to the care of the sick. As a knight, Caravaggio would have had to take vows of poverty and obedience. He seemed an odd fit for the Knights of Malta, and they for him. But the leader of the order, Alof de Wignacourt, was a man who liked his portrait painted, and Caravaggio liked his creature comforts and honorifics. It was a match made in Malta.

Figure 2.6. Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1607–1608. The Louvre, Paris.

Caravaggio depicted the vainglorious Wignacourt as both dashing and wise (figure 2.6), in full dress armor. He is also holding a large club or baton across his groin, just in case one had any doubts about the extent of his masculinity. As a convicted murderer, Caravaggio was technically ineligible to become a knight, but there are always exceptions, and after a letter to the Pope (whose portrait Caravaggio had painted before the incident at the tennis court), he became a Knight of Malta in July of 1608.

To essentially seal the deal, Caravaggio painted a new altarpiece work for Wigna-court, The Beheading of St. John the Baptist (see figure 2.2, at the opening of the chapter). This is a truly exceptional work, for a number of reasons. To begin, it is twelve feet high and seventeen feet across. The people depicted are all basically life-sized. Next, it is an altarpiece painting in a chapel, intended to inspire religious devotion. St. John is not quite dead, but the job is being finished by the executioner who holds a dagger behind his back and is about to employ it. Blood squirts from the neck of John onto the pavement. The blood then becomes Caravaggio’s signature, the only known time that he signed a painting. Thus, Caravaggio tells us that he has done this, and in fact, the executioner looks not dissimilar to Caravaggio. The allusion to Caravaggio’s killing of Ranuccio Tomassoni is as plain as can be.

Even as he becomes a knight in a religious order dedicated to the care of those in need, Caravaggio cannot resist the urge to flaunt his inglorious past, and he does so in the house of God. The painting declares, “Here I am! Knight of Malta! The greatest of artists. Killer of Tomassoni in a duel. I am Caravaggio—just as it says there in the blood of John the Baptist.”

But it did not last. By October of 1608, not even three months after being made a knight, Caravaggio had traded his residence and studio and moved into the less commodious (and more malodorous) quarters of the dungeon of Castel St. Angelo. He appears to have engaged in a dispute with a senior knight, and with rumors of bloodshed, Caravaggio turned light into dark—chiaroscuro, once again. Ever resourceful, Caravaggio escaped the dungeon and headed off to Sicily. In all likelihood, his escape was facilitated by Wignacourt, who could not formally forgive Caravaggio, but could ensure that he did not spend his life in a dungeon. No doubt when Caravaggio told the tale of his escape in the bars and brothels of Sicily and Naples, it involved cunning and courage more than connections and collusion.

The Final Years

The last two years of Caravaggio’s life were a living hell for him. He still had a bounty on his head from killing Tomassoni, and now there were worries that whomever he had offended in Malta was also in pursuit. Although he continued to work, producing some amazing works, he moved often and reportedly slept with a dagger under his pillow. In 1609, he was attacked by a gang outside a tavern in Naples and severely beaten, his face disfigured.

What is generally believed to be his last work is also perhaps the most emblematic of his troubled but incredible life and career. David with the Head of Goliath (figure 2.7) presents the severed and still-bleeding head of Goliath held by a David who is not triumphant nor proud, but rather displays consternation, or even a degree of pity for the slain giant. This painting is Caravaggio’s biography: clearly Goliath, and possibly David, are images of Caravaggio. He has painted himself as the defeated and grotesque giant head but also as a youth whose whole life is still ahead of him, who seems to be looking at the fate that he holds in his hand, thinking, “I did this . . . to myself.” Caravaggio died in a small town called Porto Ercole of a fever while desperately trying to return to Rome where he had hoped he would be pardoned for his murder of Tomassoni. As Giovanne Baglione, Caravaggio’s nemesis and later biographer put it, “He died as miserably as he had lived.”

Figure 2.7. David with the Head of Goliath, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1610. Galleria Borghese, Rome.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:David_with_the_Head_of_Goliath-Caravaggio_(1610).jpg

Caravaggio’s Era and Style

Caravaggio lived during an era of astonishing change, innovation, and creativity. As he was creating his dramatic works and changing the nature of painting, Shakespeare was working on Macbeth and Cervantes was writing Don Quixote. Galileo was inventing the thermometer, improving the telescope, and arguing that the earth revolved around the sun, and not the other way around (that did not turn out well for him). The Dutch were “discovering” Australia, and not to be outdone, the English sent an expedition to found the first permanent colony in the New World: Jamestown.

In Italy, life was confusing. Well, it’s actually difficult to say “In Italy,” as the Italian peninsula had different rulers in different regions, and who ruled whom changed often in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Milan, where Caravaggio was born, was under Spanish rule at the time, as was Naples, where he fled after killing Tomassoni. Rome was under the control of the Pope. Florence and Venice were republics unto themselves. You needed a scorecard.

Mannerism

Mannerism is a style of painting that followed the Renaissance and preceded Baroque. It was essentially a highly stylized and exaggerated version of the high Renaissance. Body parts are often elongated and dramatically presented. Compositions emphasize elegance and sophistication. Notable Mannerist artists are Pontormo, Tintoretto, Bronzino, Parmagiano, and El Greco.

Painting and sculpture, too, were undergoing a revolution, and Caravaggio worked in the vanguard. In some respects, he could not have been better situated. The style of the day, as Caravaggio began to work, was known as Mannerism. It was basically a very fussy version of the late Renaissance. The ideals of beauty, harmony, and proportion were exaggerated in Mannerism for dramatic effect. The aptly named Madonna with the Long Neck (figure 2.8) by Parmagiano, is a good example of Mannerism. Not only is the Madonna’s neck long, so are her hands, and while we at it, the baby Jesus is impossibly long. There is a column and a sculpture in the background, and drapery, along with a vase in the picture. Just like the manger in which Christ was born!

Figure 2.8. Madonna with the Long Neck, Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola, “Parmagiano,” 1534–1540. Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

It is not surprising that Caravaggio rejects it all. Contrast the long-necked Madonna with Caravaggio’s The Crucifixion of Saint Peter (figure 2.9). This is a real man really being crucified. He is twisting to his left on the cross and looking down at the nail holding his left hand to a wooden beam as he is being crucified head down (as he had requested because he felt he was not worthy of a death so similar to Christ’s). Instead of elaborating on the scene in the background, Caravaggio strips it bare and forces us to focus on the act of the crucifixion. Three men are going about the difficult business of executing their assignment. There is real weight to be lifted here, and they strain at their task.

Two items of note here. First, the model used for Saint Peter here looks strikingly like the saint on the right in The Supper at Emmaus in the “A Closer Look” feature at the end of the chapter (figure 2.10). One can see models used again and again in Caravaggio’s work (only so many people available to serve as models). Second, the use of chiaroscuro seems to be almost extreme in this work. There is basically nothing but the players and the action here. Everything else is in darkness. Caravaggio used this technique so intensely that it was given a separate name, called tenebrism.

As far as can be told from X-ray analysis of Caravaggio’s work, he did not spend time on preliminary drawing on the canvasses he painted, rather taking a quick sketch with the back end of his brush.8 This is not to say that he did not make preparatory drawings of his works, but rather, once he knew what he wanted to do, he wasted little time in working out details on the canvas itself. He simply dove right into the work. Would we have expected anything else?

Figure 2.9. The Crucifixion of Saint Peter, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1601. Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Martirio_di_San_Pietro_September_2015-1a.jpg

Final Thoughts on Caravaggio

The basic question that is posed in this book is why we like art made by people we would find less than admirable human beings, if not outright repugnant? Caravaggio is an excellent starting place for such a discussion, as his greatness and his disreputableness are not in question. Would we be intrigued less by these works if we knew they were done, say, by a gentle monk, well-liked by everyone, or would that make them more admirable? What role does the nature of the artist play in the reception of the artist’s oeuvre? Caravaggio’s firsthand understanding of passion, lust, anger, violence, and bloodshed seem to be communicated not only in the subject matter he presents, but also in his incredibly dramatic portrayal of his subjects. But if we engage in the aesthetic thought experiment of imagining the same works, but a different artist, where do we arrive? Are our reactions the same, or have we been influenced by what we know, and if so, how, and how much?

Figure 2.10. The Supper at Emmaus, Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1601. National Gallery, London.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Supper_at_Emmaus-Caravaggio_(1601).jpg

Working in Rome in 1601, from a commission from nobleman Ciriaco Mattei, Caravaggio depicted the supper at Emmaus when Christ revealed himself to two of his disciples as having risen after the crucifixion. He had disguised his appearance (in Caravaggio’s work, in part by having no beard), and what Caravaggio presents is the moment when the disciples realized who he was. Caravaggio employs his characteristic chiaroscuro technique to heighten the drama of the moment. The disciples are seated and the man standing to the left is the server at the inn where the supper takes place. Caravaggio later painted this event in a more subdued fashion.

A Closer Look: Caravaggio’s The Supper at Emmaus

The picture featured in figure 2.10 is The Supper at Emmaus by Caravaggio. Take a look at the image and the accompanying label, and think about what your reactions are before moving ahead with reading this page. Take your time.

Welcome back. Let’s start by looking at the painting at kind of a “big-picture” level. We see Christ in the direct center of the painting, framed by the disciples and the server of the dinner (standing and wearing a hat). This is the moment when Christ lets his disciples know that they are in his holy presence. The disciple on the right throws his hands out to his sides. His left hand appears to come completely out of the painting.

Caravaggio is working in a new style from his Renaissance and Mannerist predecessors. He is painting in a style called Baroque. In contrast to the more formal and refined Renaissance approach, Baroque is more real, more immediate. The people in Baroque paintings are not idealized; they are actual people. There is honest emotion and movement in this painting. Christ reaches out to us; the disciple on the left is jumping out of his chair. These are people whom we almost might know.

We don’t know if Caravaggio was a particularly religious individual, but with his whoring, drinking, and brawling, if he were, we can safely assume he was somewhat short of “devout.” But what he seems to be saying with this painting is that “if Christ rose from the dead, and if, in disguise, he encountered two of his apostles on the road to Emmaus, and if at one point during dinner Christ revealed himself to them—if all that really happened, then . . . this is what it looked like!” Caravaggio wants to plunk us down right in the middle of that scene. He wants us to be able to richly imagine being there with Christ. In fact, you can imagine you are the apostle on the left. You are in that chair, perhaps leaping out of it, or perhaps what is depicted is him (you) pulling it up closer to be nearer to Christ.

Now look at how Christ is depicted. He and the disciples appear to be European, not Middle Eastern. The apostles depicted here may have been compatriots of Caravaggio, wastrels in the evening, and models of apostles during the day. In Christian art, the holy family and the disciples frequently seem to hail from western Europe. Put that aside for now. Look at how Caravaggio has made Christ beatific. Look at his face and his arms; peacefulness, even holiness, is what you see. In fact, if you hold your arms and hands in the way that Christ has them, and look down in a humble fashion, you may well sense a certain peacefulness yourself. That is what Caravaggio is communicating. And while contemplating this, and the disciples’ reactions to him, remember that in the next instant in this scene, Christ vanishes. Allow yourself to imagine that as if it happened just that way.

Trompe l’oeil

Trompe l’oeil is French for “trick of the eye.” It basically refers to art that is so realistically portrayed that it tricks the viewer into believing it is real.

Let’s shift gears and look at technique. This painting strongly employs the chiaroscuro technique described earlier. Note how Caravaggio has cleverly cast the shadow of the server on the back wall to form a dark frame against which Christ stands out even more dramatically. Caravaggio not only uses chiaroscuro, but also symbolism, foreshortening, and trompe l’oeil (French for “trick of the eye,” see textbox). The symbolism here includes the slightly rotting apple in the basket, reminding us of the fall of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden (Caravaggio is not bothered that the resurrection took place in the spring and apples are an autumn fruit). The bottle of water through which light passes without breaking the glass represents virgin birth, and the bread symbolizes the body of Christ. Foreshortening can be seen in how Caravaggio has stretched out the arms of the apostle on the right in either direction. The trompe l’oeil involves making the basket of fruit and the disciples seemingly come out of the picture, and the bottle of water to look absolutely real.

Now, if you would, take another long look at this work. What else do you see? Put yourself in that work. Imagine that you are there, learning that this stranger you have invited to join you for dinner turns out to be Christ. Your Christ! Your savior! If you are not Christian, just let Caravaggio take you back to an imagined dinner that is some combination of the first century and the seventeenth. In either case, let yourself enjoy—the craftsmanship, the emotion, the drama, the movement, and the fact that this work is four hundred years old.