C

Cane Mills

Cane mills are used to squeeze the juice from sorghum cane or sugar cane. The extracted juice is then reduced to a syrup in a suitable evaporator pan. Many communities had at least one such cane mill to provide a source of corn syrup and sorghum for the kitchen. Eventually, most of this work was taken over by commercial refiners. But even today, a few cane mills remain for the annual production of these products. As with many kinds of farm equipment, cane mills and related items have almost no value to someone uninterested in them, but have substantial value to those who wish to perpetuate and preserve the art.

Blymyer Iron Works Co., Cincinnati, Ohio

Prior to the 1880s, cane mills were rarely found on farms. Commercial establishments were found in nearby towns. Aside from animal power, there was no way to operate the crushing rolls, unlike commercial establishments with steam engines. Companies like Blymyer probably were established around a foundry business, making the heavy cane mill a natural addition.

N.O. Nelson & Co., St. Louis, Mo.

By the 1880s, several companies were offering cane mills, sometimes calling them sorghum mills. This one was made by N.O. Nelson & Co., St. Louis. It was a powered mill and could be driven either by attaching a belt pulley to the countershaft or by driving it from the tumbling rod on a horsepower.

George K. Oyler Co., St. Louis, Mo.

An 1887 advertisement shows the Pioneer Cane Mill as built by George K. Oyler Co., St. Louis. This one was attached to four sturdy posts set in the ground. The large casting at the very top carried one or two sweep arms. One or more horses was hooked to the sweeps and walking “round-and-round,” they turned the massive iron rolls.

Alex. Magee and Co., St. Louis, Mo.

In an 1887 issue of Farm Machinery, an extensive article detailed the various makes and models of cane mills built in St. Louis. Included was The St. Louis, made by Alex. Magee & Co. Rather than use vertical rolls, this one featured horizontal crushing rolls. Sweep arms were attached to the large gear atop the mill, and the horsepower used to operate the mill was genuine animate horsepower.

Did You Know?

The value of early ear-corn cutters can be more than $100 for one in good condition.

George K. Oyler Co., St. Louis, Mo.

A 1907 advertisement details the vertical cane mill from Cook Cane Mill & Evaporator Co., St. Louis. During the 1880s, the Cook mill and the Cook evaporator appear to have been built and sold by Geo. K. Oyler Co., St. Louis, with Cook eventually coming to dominate the market. Thousands of these mills were built, but only a few remain. The sorghum cane was first stripped of its leaves and heads and the stalks were fed through the rolls. The offal came out the other side, while the sweet juices were caught in a vessel below.

A 1922 catalog of Cook Cane Mill & Evaporator Co., illustrates numerous sizes and styles of cane mills, with this Superior model being one of the largest. Squeezing all the juice from the cane required considerable power, but by the 1920s this could be derived from various sources. Eventually, the popularity of the home-made product declined and commercially produced syrups came to a dominant position.

Did You Know?

Old cream cans, sometimes known as shipping cans, can often bring $20 to $40 or much more for an unusual or unique design.

By the 1880s, Cook’s Rocking Portable Evaporator was an established product. The operator was constantly busy stoking the fire and skimming the foam and offal from the surface of the boiling syrup. During this process, the volume of the juice was reduced by perhaps 90%. Finally, the entire unit could be rocked or tilted slightly and the finished sorghum could be released from a convenient tap on the side of the pan.

For permanent locations, Cooks’ Stationary Evaporator could be set up, using either the best quality of galvanized steel or even better, a cold-rolled copper pan. Gates were used to regulate the flow of juice, and, as the juice boiled down in its section, it was transferred to the next and so on, until finally being released into waiting barrels and finally into jars. The first cold autumn day was an ideal time to sample the new batch of sorghum over a platter of buckwheat pancakes!

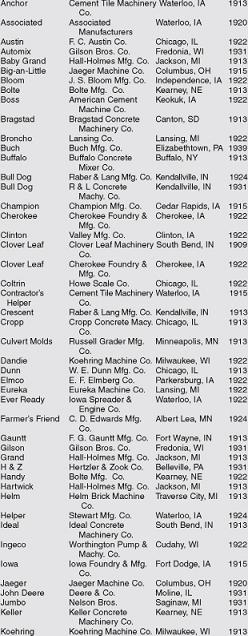

Trade Names

Cement Mixers

While not truly a farm implement, small cement mixers became very popular in the early 1900s. No longer did farmers have to rely on plank or stone floors; they could now mix concrete by themselves for enduring walls, floors or for other purposes. With the development of the cement mixer, it was but a short time until there were a few in almost every community. When it came time for a major concrete job, everyone pitched in to help. Although drum mixers are still made at the present time, the older machines, especially those with their own gasoline engine, can oftentimes bring several hundred dollars. However, in these cases, the buyer usually places much more value on the engine than on the mixer itself.

Cherokee Manufacturing Co., Cherokee, Iowa

An unusual cement mixer design was the 20th century, offered in 1912 by Cherokee Manufacturing Co., Cherokee, Iowa. This one dry-mixed the materials for the first six feet of travel, at which point water was added for the final part of the mix. When it emerged at the rear of the machine, the concrete dropped into waiting wheelbarrows. According to advertising of the time, the company used its own engine, an example of which is shown in this illustration.

Cement Tile Machinery Co., Waterloo, Iowa

Cement Tile Machinery Co., Waterloo, Iowa, helped popularize the cement mixer with this 1913 version. The drum was loaded with sand, gravel, cement and water in certain proportions; after a short mixing time, it was ready to be discharged into a waiting wheelbarrow. The engine appears to have come from Waterloo Gasoline Engine Co., in Waterloo.

Hartman Co., Chicago, Ill.

Continuous mixers enjoyed a certain popularity (as shown by this Majestic from Hartman Co., Chicago. This $40 outfit was illustrated in its 1919 catalog. Mixing concrete was a very labor intensive job, requiring one man to scoop sand, another man or two with gravel, another with cement and water, someone to run the machine, several more to push loaded wheelbarrows to the site and still more men to level and smooth the new concrete.

Standard Scale & Supply Co., Pittsburgh, Pa.

Standard Scale & Supply Co., had a factory at Pittsburgh but also maintained offices in New York, Chicago and Philadelphia. Its Standard Low Charging Mixer of 1912 used a drum design, vaguely familiar with today’s “ready-mix” trucks. From the position shown, the drum turned clockwise. After being loaded, the mixer operated for a suitable time, after which a discharge door on the opposite end of the drum was opened. Depending on the circumstances, the entire load could be discharged at once or parceled out to waiting wheelbarrows.

Jaeger Machine Co., Columbus, Ohio

Jaeger Machine Co., Columbus, Ohio, became widely known for its famous Jaeger Line of mixers and other construction equipment. This offering of 1920 included a gasoline engine mounted in the house at the rear of the machine and usually consisting of an engine of 2 to 3 horsepower. Many thousands of these batch mixers were sold by Jaeger and many other companies, with a substantial number being owned by a group of farmers within a neighborhood.

Associated Manufacturers, Waterloo, Iowa

Beginning about 1912 and continuing for several years, Associated Manufacturers in Waterloo, Iowa, offered its Amanco concrete mixer. Advertising of the time noted that it would “meet the needs of the farmer and small contractor.” This one sold for $115, complete with a 2-1/4 horsepower Associated engine. The mixer was of the continuous design. On today’s market, a complete unit, like this one, could bring somewhat more than just the value of the engine; the latter would by itself likely fetch more than $300 in reasonably good condition.

Trade Names

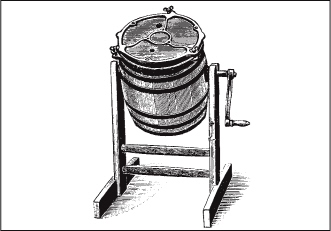

Churns

Butter churns have a long history and, in some form or other, go back to the beginning of butter. However, the 1880s saw new developments, necessitated by the rapid settlement of the Midwest and Western states. The transportation system at the time was poorly developed, so the transport of sweet milk or cream was nearly impossible. To best use this cash commodity, the cream was separated from the milk, with the cream being converted into butter.

Like many aspects of American life, this too came to an end. Of interest, though, many farmers churned their own butter, at least occasionally, during World War II, due to the scarcity of many commodities. The author churned many a batch with an old Dazey churn. Sometimes, it was easy, taking but 15 or 20 minutes. Other times, it was a lot of cranking, taking 45 minutes or more to get that ripened cream to turn into butter. Today’s prices vary widely. An ancient box or barrel churn can oftentimes fetch $500 or more, while the smaller and more common paddle churns often sell for $50 or more.

Did You Know?

A simple 7-inch foot-operated lathe from W.F. &John Barnes Co., sold for $40 in 1903; today, its value as a collectible could be $400.

H.G. Batcheller & Son, Rock Falls, Ill.

This barrel churn of 1887 was built in many variations by numerous companies. Most consisted of a wooden barrel with a removable lid. Once it was loaded with ripened sour cream, it was slowly turned until the conversion to butter came; this could take nearly an hour. Of course, after the job was done came the task of thoroughly cleaning up the churn so as to leave it sweet and clean for the next batch. This one was made by H.G. Batch-eller & Son, Rock Falls, Ill.

C. Mears & Son, Bloomsburg, Pa.

Numerous companies of the 1880s and onward made churns as well as a “dog power” to do the work. In this 1892 advertisement, C. Mears & Son, Bloomsburg, Pa., offered a combination of its “Washer,” “Propeller Churn” and “Dog Power.” Its claim was that a 40-pound dog could operate either machine with no problem at all.

Anyone having additional

materials and resources

relating to American farm

implements is invited to contact

C.H. Wendel, in care of

Krause Publications, 700 E. State St.,

Iola, WI 54990-0001.

Goshen Churn and Ladder Co., Goshen, Ind.

Many small churns were available for household use. These included the inimitable Dazey churn with its glass jar, as well as many others with a metal or wood container. Of the latter, the Oval Churn of Goshen Churn & Ladder Co., Goshen, Ind., typifies the lot. This one of 1903 was intended for making fresh butter for the household, as compared to making larger quantities for private or commercial sale.

M. Rumely Co., LaPorte, Ind.

Among its many other interests in 1913, the M. Rumely Co., LaPorte, Ind., offered its Rumely Home Creamery as part of its line. Ostensibly, the company was much more famous for its Ideal threshers and OilPull tractors than for its churns; consequently, it wasn’t in the churn business for very long. The advertising accompanying the Rumely Home Creamery pointedly noted that it could “add creamery profits to the farmer’s profits” to woo potential purchasers.

Trade Names

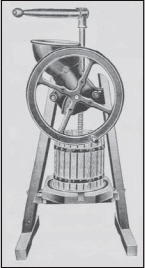

Cider Mills

The cider mill, as illustrated here, had taken its general form by the 1860s. Two major components were needed, the grinder, which reduced the apples to a pulpy mass, and the press, which squeezed out the juice. Fresh apple cider has long been a delicacy, with a fair portion being made into apple wine, hard cider and other products. Only a few styles and sizes are shown here; today’s values vary widely. A small single drum unit might sell for $50 to $100, while a fancy double-drum unit might bring twice that figure. Again, the value is largely dependent on the condition of the machine, as well as its popularity in a given area.

P. P. Mast & Co., Springfield, Ohio

An 1887 advertisement shows the Champion Cider Mill from P.P. Mast & Co., Springfield, Ohio. This one was made in three different sizes and was of the double-drum design. While one person fed apples into the hopper, another turned the crank, reducing them to pulp and filling the slatted open drum below. While this was taking place, another person was busy squeezing the juice from the pulp, using a heavy lever on the top of the feed screw. A barrel or vat below the floor of the mill caught the delicious apple juice. Exactly a year later, the identical engraving is shown in an advertisement from the Superior Drill Co., also at Springfield.

P. P. Mast & Co., Springfield, Ohio

The Improved Buckeye Cider Mill from P.P. Mast & Co., was patented already in 1864. It was a big machine, and, with enough manpower, it could reduce many bushels of apples to cider in a short time. This Springfield, Ohio, company pioneered a great many farm implements, in addition to the cider mill shown here.

Hocking Valley Manufacturing Co., Lancaster, Ohio

A pioneer farm implement builder, the Hocking Valley Manufacturing Co., was located in Lancaster, Ohio. Its implements and machines were built to the highest standards rather than building to a price. This 1904 example shows its Junior cider mill; it featured a cast-iron case for the grinder, along with other important features. Virtually all these machines were built to last a lifetime; in fact, a substantial number have survived for several lifetimes.

A. B. Farquhar Co., York, Pa.

The American Cider Mill of A.B. Farquhar Co., featured a substantial flywheel to assist the grinding of the apples. Of course, this added still more weight to the machine, but added weight was not a deterring factor in most early farm-machine design. Note the heavy wooden bar on the floor. It was furnished with the machine. After turning the screw down by hand as far as possible, the lever raised the pressure still more, until almost all the juice was extracted, leaving a rather solid cake of pumice at the bottom. This was hauled away for livestock feed. Meanwhile, a full drum was moved under the screw while the empty one went back beneath the grinder.

By the 1920s, the cider mill had undergone noticeable changes. Many of them were of much lighter design, and, while still substantial, the lighter design also lowered the price. This Majestic double-tub cider mill of 1920 came from the Hartman Co., in Chicago. It sold for the princely sum of $19.85, plus freight.

Hartman Co., Chicago, Ill.

For household use, Hartman Co., of Chicago, offered this single-tub design in 1920. It was priced at only $13.75, but the lower price meant a sacrifice in convenience. With this unit, the tub was filled from the grinder and then squeezed by the screw. As an additional inducement, Hartman offered easy credit terms with a full year to pay.

Trade Names

Clover Hullers

Clover was recognized as an important crop in England as early as 1650. With the earliest settlements in America, clover became an important forage crop, its greatest problem being that of securing the seed. Eventually, farmers learned to cut the first crop for hay. Then, if the seed failed to develop on the second crop, all was not lost for the season. Secondly, by cutting the second crop, the seed heads ripened more uniformly, resulting in a much better chance at getting a yield. For many years, a yield of two bushels of seed per acre was worthwhile, while four or five bushels was an excellent return. Getting as high as eight bushels of seed per acre was a virtual bonanza.

A study of early U.S. Patent Office records shows a small amount of activity up to the 1850s. However, the most significant development was that of John Comley Birdsell, who was granted his first clover-huller patent in 1855. He commenced building hullers on his farm at that time, continuing at West Henrietta, N.Y., until 1863, when he moved to South Bend, Ind. Testifying to his designs, the Birdsell hullers saw little change from 1881 until the end of the company in 1931. At that time, it was bought out by Allis-Chalmers Manufacturing Co.; the latter was developing an All-Crop combine that could successfully harvest clover seed right in the field. That put an end to the need for clover hullers.

Several other manufacturers built clover hullers in competition with the Birdsell. While some may have matched it in quality, it is unlikely that any exceeded it. Others attempted to market combination machines—that is, a grain thresher and clover huller in a single unit. These met with mediocre success.

John C. Birdsell, West Henrietta, N.Y.

This New Birdsell clover huller of 1895 marked the 40th anniversary of the first Birdsell huller in 1855. John C. Birdsell gained his first huller patent that year, beginning the manufacture of clover hullers on his farm near West Henrietta, N.Y. This continued until 1863 when he moved the entire operation to South Bend, Ind. A major factor in this move might well have been the fact that, at the time, Indiana was the leading producer of seed clover.

John C. Birdsell, West Henrietta, N.Y.

The Birdsell Clover Huller of the 1920s was built in several sizes and could be equipped in several different ways. The machine shown here with its feed board swung back over the top for transportation was a hand-fed machine, requiring people to fork the clover toward the threshing cylinder. However, it was equipped with a wind stacker to carry away the leaves and stems. Birdsell huller owners never ceased to praise their machines. One owner from Elgin, Ill., reported to the company that he had a machine built in 1860, and it had been in used every season for 55 years, with not more than $5 in expense during that time.

Aultman & Taylor Machinery Co., Mansfield, Ohio

Aultman & Taylor Machinery Co., Mansfield, Ohio, illustrated its clover huller in an 1893 catalog. Its salient feature was the method of driving both cylinders with a single belt. The upper cylinder was designed to remove the heads from the stems, with the hulling or rubbing out of the seeds being achieved in the lower cylinder. For many hullers, a capacity of five or six bushels per hour was the maximum; even the largest machines only had a capacity of perhaps 15 bushels per hour.

Newark Machine Co., Newark, Ohio

Newark Machine Co., Newark, Ohio, offered its Victor Double Huller in this 1895 advertisement. The clover was fed by hand into the threshing cylinder, with the straw passing out over vibrating racksto the rear. Hulling was achieved in a drum beneath the threshing cylinder. Since much of the seed escaped with its husk the first time through, a large tailings or return elevator carried it back for a second pass. After this, the seed went through a small re-cleaner seen here on the side of the machine.

Orrville Machine Co., Orrville, Ohio

As otherwise noted, a few companies attempted to market a combination grain thresher/clover huller on a single frame. One of these was the New Combined Champion from Orrville Machine Co., Or-rville, Ohio. This 1895 model had already been on the market for 20 years, but little further information has been found on this machine after the early 1900s. The market was limited first to those who would likely be harvesting clover seed; most of these farmers preferred a thresher for threshing and a clover huller for hulling.

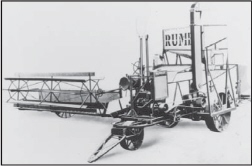

M. Rumely Co., LaPorte, Ind.

A few of the large threshing-machine builders opted into the clover-huller market. One of these was the M. Rumely Co., LaPorte, Ind.; after 1914, this was known as the Advance-Rumely Thresher Co. This 1904 model was built largely along the lines of the Rumely grain threshers and it is likely that a great many parts were interchangeable. The re-cleaner is obvious above the left rear wheel. Re-cleaning was necessary to help remove weed seed and other foreign material left behind by the huller.

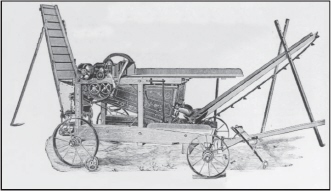

Reeves & Co., Columbus, Ind.

Reeves & Co., Columbus, Ind., was another large thresher manufacturer that entered the clover-huller business, at least for a brief time. Reeves was bought out by Emerson-Brantingham Co., Rockford, Ill., in 1912. Thus, the company’s career in the huller business was rather brief, if, in fact, it continued up to the time of the E-B takeover. With the advent of the Allis-Chalmers All-Crop combine in the 1930s, clover hullers quickly fell into obsolescence, since farmers were able to harvest the seed crop directly in the field. One man with an All-Crop combine instantly replaced the large crew needed with the time-honored clover huller.

Trade Names

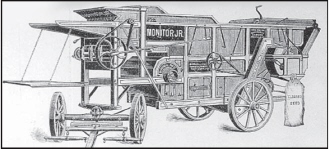

Combines

The word “combine” is actually an abridgment of the earlier term, “combined harvester-thresher.” The idea of combining the two operations of harvesting the standing grain and taking the grain to the bin, while leaving the straw in the field, had been extant for many years prior to the 1900 Holt. This machine gained but slight interest, but the company persisted and finally was completely successful by 1915. International Harvester was another major player at the time and was hard at work developing a combine of its own. Other companies took notice of the new developments and, by the early 1920s, there was a number of companies with combines in the field.

It is not the purpose of this book to delineate the entire development of the combine industry. That has been done in various other books, especially the author’s book 150 Years of International Harvester (Crestline/Motorbooks, 1981). This title provides an in-depth look at Harvester’s long struggle to market a completely successful machine. This came rather slowly, despite the fact that Harvester poured more money into new product research than almost any other American farm-implement maker.

To completely overlook the combine in this book would likewise, be a grave error, so the author had chosen a middle-ground to present a few examples of early combine design, doing so in a limited space, lest other significant machines and implements be left out completely.

Until the development of the Allis-Chalmers All-Crop combine in the early 1930s, virtually all combines used the time-honored spike-tooth cylinder featured in the threshing machine. The early machines were big, heavy and rather complicated. It could well be said that these early combines were essentially a small threshing machine mounted so that a cutterhead could feed the cut grain into the cylinder. The All-Crop combine constituted the first major change in combine design and heralded a new era for the combine.

Another significant design emerged from the work of Curtis C. Baldwin of Kansas. Already in 1913, he developed his vacuum thresher, followed later by more-or-less conventional designs. The Baldwin combines gained a considerable reputation, finally being acquired by Allis-Chalmers.

Not to be forgotten was the significant work of Massey-Harris Co., developing the first successful self-propelled combine in the late 1930s. From this first design sprang today’s ultra-modern machines.

Holt Manufacturing Co., Stockton, Cal.

Caterpillar combines were a direct descendant of the Holt combine, development of which began as early as 1900. This 1930 model epitomized combine development of the time, even including Timken roller bearings to reduce friction and consequent power losses. Holt Manufacturing Co., was an early pioneer in the combine business, but opted to concentrate on its tractor and construction machinery business, selling the combine line to John Deere in 1935.

Curtis C. Baldwin Co., Joplin, Mo.

The Savage combined tractor-harvester-thresher was a 1920 design of Curtis C. Baldwin. At the time, Joplin, Mo., was hoping to acquire a new factory to be built for this unique machine. For reasons unknown, this design did not meet with great success, although later Baldwin designs were very popular, especially in the wheat belt.

International Harvester Co., Chicago, Ill.

The McCormick Harvester-Thresher of 1920 was capable of harvesting from 15 to 20 acres per day. It was ordinarily furnished with a four-cylinder engine, but could also be furnished with a ground-drive, omitting the engine. In this case, anywhere from eight to 12 horses were required to pull and operate the machine.

Avery Farm Machinery Co., Peoria, Ill.

Avery Farm Machinery Co., at Peoria, Ill., developed a combine in the 1920s, continuing to market it in small numbers into the 1930s. Like virtually all combines of the time, it cut the grain and delivered it sideways to the threshing cylinder. Avery offered several sizes and styles, with headers ranging up to 16 feet in width.

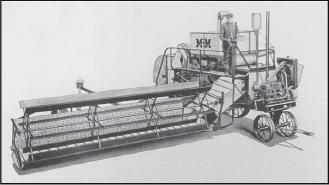

Minneapolis-Moline Co., Minneapolis, Minn.

Minneapolis-Moline Co., resulted from a 1929 merger; prior to that time, one of the partners, Minneapolis Threshing Machine Co., had been busy developing a combine. As with most others of 1930, the cut grain was delivered by a conveyor into the cylinder. To leave the field and travel down a road, the header was detached and remounted on its own wheels for separate transportation from the threshing unit.

Massey-Harris Harvester Co., Batavia, N.Y.

Massey-Harris Harvester Co., was headquartered in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, but had a factory at Batavia, N.Y. Massey developed its own combine during the 1920s, marketing this big No. 9 Combined Reaper-Thresher in 1927. It was made in 12-foot and 15-foot sizes. Its smaller machine, the No. 6, used a 10-foot cut.

Massey-Harris Harvester Co., Batavia, N.Y.

Massey-Harris tested its No. 20 self-propelled combine in late 1937. Limited production of this machine ensued in the 1938-40 period. Originally tested in Argentina, the No. 20 was especially designed for and marketed on the West Coast. Even though production was limited and the machine had its shortcomings, it marked the beginning of the new era of self-propelled combines.

Massey-Harris Harvester Co., Batavia, N.Y.

Massey-Harris No. 21 self-propelled combines first emerged in 1940. Even though the demands of World War II were great, the company was able to build a limited number of these machines during the war, since they were able to bring in the crop, even with the limited manpower then available. Thus came the famous Massey-Harris Harvest Brigade. These combines were to be sold only to custom operators who would harvest at least 2,000 acres of grain per season and under the supervision of Massey-Harris.

Deere & Co., Moline, Ill.

Deere & Co., Moline, Ill., was another of the major companies to enter the combine business during the 1920s. Its No. 1 combine of 1928 is shown here, being pulled by a John Deere Model D tractor. The combine is equipped with its own independent engine, as evidenced by the high intake pipe and the high exhaust well above the dust zone of the combine. At this point in time, two men were required—one to drive the tractor and the other at the controls of the combine.

Advance-Rumely Thresher Co., LaPorte, Ind.

Advance-Rumely Thresher Co., LaPorte, Ind., came forth with its combine in the mid-1920s. It followed the same general design as others of the period, with a side-mounted header, independent engine and heavy construction. The Rumely was offered in numerous sizes and styles, even including a special hillside model. Rumely was absorbed by Allis-Chalmers in 1931.

Nichols & Shepard Co., Battle Creek, Mich.

Of all the old-line thresher manufacturers, Nichols & Shepard at Battle Creek, Mich., was one of the most conservative in its designs. However, while many of the thresher builders refused to get into the combine business, N&S came out with its own design in the 1920s, offering several sizes and styles. This rugged machine typifies the N&S design and apparently was sold to some extent, particularly in the wheat belt. Nichols & Shepard merged with others to form the Oliver Farm Equipment Co., 1931.

Allis-Chalmers Mfg, Co., Milwaukee, Wis.

Allis-Chalmers ventured forth with its All-Crop Harvester in 1931. Early production saw the need for further changes; by 1932 the All-Crop had come into its own realm as the combine to imitate. Soon, the side-mounted header came to an end. In its place came the direct-cut machine, such as the All-Crop. Another innovation was the standard use of a PTO shaft on this light-weight machine, obviating the necessity of an auxiliary engine. Only the earliest of the All-Crop combines were equipped with the steel wheels shown here; the remainder used rubber tires. One exception may have been the production of a few All-Crop combines on steel during World War II, due to the scarcity of rubber.

Did You Know?

Old sickle grinders sometimes have a substantial antique value, occasionally selling for $50 or more.

J. I. Case Co., Racine, Wis.

In 1940, J.I. Case Co., offered this Model F combine as part of its overall line. Case had pioneered in the threshing machine business and had been building combines since the 1920s. However, Case, like most others, was soon to adopt the in-line method of combining grain, just as had been pioneered by the Allis-Chalmers All-Crop. The Case Model F combine shown here cut a 54-inch swath.

Wood Bros. Thresher Co., Des Moines, Iowa Wood Bros., Thresher Co., Des Moines, Iowa, was a

Wood Bros., Thresher Co., Des Moines, Iowa, was a well-known threshing machine manufacturer. During the 1930s, the Wood brothers developed several new and innovative machines, including this all-steel combine with a 5-foot cut and using a threshing cylinder the full width of the machine. However, Wood Bros. was a small company compared to Case, International Harvester and others. Thus, it faced tremendous competition and World War II, severely limited farm-equipment production. Eventually, Wood Bros. was taken over by the Farm Equipment Division of Ford Motor Co.

Trade Names

Corn Binders

Although limited activity probably took place sooner, there were no commercially practical corn binders prior to 1890. At that time, D.M. Osborne Co., Auburn, N.Y., came out with a practical machine. About the same time, McCormick Harvesting Machine Co., Chicago, introduced a unique push-type corn harvester, but it was not a success. Despite this, McCormick later went on to claim that it had built the first “corn harvester.” Technically, at least, that may have been true; in practical terms, though, it was Osborne who led the field.

Agriculturists of the 1880s were promulgating the concept of converting standing corn into silage, regarding the latter as very palatable and nutritious for livestock. The idea caught on; during the 1890s, there was a flurry of activity to build corn binders for harvesting the standing corn. Likewise, there was a boom in the ensilage cutter business (of course, the business of erecting silos was doing quite well, too).

There’s little to be said about corn binders—their purpose is obvious and for those who have worked around them, lugging those heavy bundles of green corn was hard work. However, there was little other choice until the field cutter began impacting the market in the 1940s. Today, a good corn binder is not easy to find. They were completely useless for any other purpose, so the great majority were scrapped. A corn binder in reasonably good condition will bring in excess of $200 today. A nicely kept one in original condition might bring substantially more.

International Harvester Co., Chicago, Ill.

An early advertisement of International Harvester Co., illustrates McCormick’s “Self-Binding Corn Harvester.” The term was later shortened simply as “corn binder.” McCormick claimed it was the first on the market, although it appears that Osborne at Auburn, N.Y., was the first with a commercially successful machine. International Harvester continued to offer this machine at least up to 1953.

Deering Harvester Co., Chicago, Ill.

Deering Harvester Co., Chicago, was a strong competitor to the McCormick interests. In 1899, Deering came out with this “horizontal corn binder.” It was uniquely different, in that it cut the standing corn, laid it down for binding and discharged the finished bundles. Despite its unique design, the Deering was eminently successful and remained in the Harvester line for many years. The artist’s rendition gives the reader an idea of how it was done. It’s more than a little unlikely that the farmer would have been dressed in suit coat, vest and tie, nor would one have been accustomed to seeing fancy, fine-boned driving horses pulling the binder.

Milwaukee Harvester Co., Milwaukee, Wis.

The Milwaukee corn binder of 1902 was a vertical design and came from Milwaukee Harvester Co., Milwaukee. In 1902, this company became a part of International Harvester. The Milwaukee corn binder also remained in the IHC line for some years, partially because the company maintained separate product lines under a single corporate umbrella into the early 1920s.

Aultman-Miller & Co., Akron, Ohio

Aultman-Miller & Co., Akron, Ohio, was well known for its Buckeye line of mowers, reapers and other implements. In the late 1890s it came out with its own corn binder, illustrating it in its 1901 catalog. My copy is written in German. This was not uncommon, since many immigrants were not conversant in the English language. To give the best possible impression of its machine, Aultman-Miller noted that “it is grounded on the right principles,” to loosely translate the German version.

Frost & Wood Ltd., Smith’s Falls, Ont.

Frost & Wood at Smith’s Falls, Ontario, Canada, offered a rather complete line of harvesting equipment, including this 1910 version of its corn and sunflower binder. Certain areas of the northern United States and southern Canada were well suited for raising sunflowers, thus this company’s reference to the crop.

D. M. Osborne & Co., Auburn, N.Y.

D.M. Osborne & Co., Auburn, N.Y., was the first to successfully market a corn binder, doing so in 1890. Its machine was on exhibit at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. No wonder this 1900 version was called the Osborne Columbia Corn Harvester. Note the interesting design of the cast-iron drive wheel.

Johnson Harvester Co., Peoria, Ill.

Johnston Harvester Co., Batavia, N.Y., illustrated this version of its corn binder in 1908. By that time, many farmers, especially dairy farmers, were convinced of the value from ensilage, so there was a ready market for silos, silo fillers, corn binders and related equipment.

Acme Harvester Co., Peoria, Ill.

Acme Harvester Co., Peoria, Ill., was a relatively small competitor in a land of giant manufacturers. Nevertheless, Acme offered this corn binder in 1914. It featured an all-steel design and this would be the trend of the future. Acme only remained in business for a few years.

Massey-Harris Harvester Co., Ltd., Toronto, Ont.

Massey-Harris was based in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and its equipment was widely sold in Canada. However, the company also made many excursions into the United States, the most famous being its 1928 purchase of the J.I. Case Plow Works at Racine, Wis. Prior to that time, Massey-Harris had acquired a few smaller concerns, so the company’s status was well established when this No. 3A corn binder was offered to the market in 1919.

Emerson-Brantingham Co., Rockford, Ill.

International Harvester divested itself of the Osborne factories in 1918, having acquired this operation some years before. In turn, Emerson-Brantingham bought up the Osborne line, offering it virtually intact for a few years. Included was the E-B Osborne corn binder of 1919 shown here. However, Emerson-Brantingham fell into financial hard times and only survived until 1928.

John Deere Harvester Works, Moline, Ill.

John Deere slowly and deliberately built its product line over the years. Until about 1912, numerous products were jobbed from other manufacturers and sold by the various John Deere branch houses. Eventually, the company acquired enough companies and developed enough of its own products to become a full-line company with everything being sold under the John Deere name. Such was the case with this John Deere corn binder of 1927.

J. I. Case Co., Racine, Wis.

When J.I. Case Co., bought out Emerson-Brantingham in 1928, it also acquired the Osborne line that E-B had bought only a few years before. For several years after the acquisition, Case continued to market many Osborne machines under the Case-Osborne trademark. Included was this attractive corn binder that featured all-steel construction. This machine continued on the market until after World War II.

Trade Names

Corn Cribs

W. J. Adam Co., Joliet, Ill.

Lest it be thought that the idea of a temporary corn crib was unique to 20th century thought, comes this Adam’s Portable Corn Crib of 1894. The manufacturer, W.J. Adam, Joliet, Ill., received Patent No. 500,459 for his invention in June 1893. The patent covered the wire picket sections used in the crib, as well as a special access door when it came time to shell the corn. Scooping the corn over the top as shown, must have been a thrilling task!

Trade Names

Corn Crushers & Slicers

By the 1880s, farmers were deluged with new ideas, inventions and concepts. Researchers were finding new ways to make livestock-raising more efficient. Great efforts were made to make livestock feed more palatable. This included a variety of corn cutters, crushers and slicers. Undoubtedly, there were hundreds of different machines produced for this purpose, many of them having a localized sale. Others were offered by major manufacturers, which likely sold many thousands of their machines. With the passage of time, new and better ways of handling ear corn were developed. Ear-corn cutters slowly faded from the scene, almost completely disappearing by 1940. Early machines have a certain nostalgic value, ranging from $20 to $25 for one in poor condition to $100 or more for one in good condition.

Sandwich Enterprise Co., Sandwich, Ill.

The Dean Patent Ear Corn Cutter was built by Sandwich Enterprise Co., Sandwich, Ill. Patented under No. 309,773, 1884, this machine was developed earlier by George B. Dean and Jeremiah Y. Burnett of Lamoille, Ill. By the time this 1887 advetisement appeared, Sandwich Enterprise Co., was already a major manufacturer of windmills, pumps, planters, cultivators, feed grinders and many other implements.

Barnes Manufacturing Co., Freeport, Ill.

Barnes Manufacturing Co., Freeport, Ill., advertised this National Ear Corn Cutter in 1887. As noted in the engraving, two vertical tubes were used to feed corn into the machine; each ear had to be fed individually from the side-mounted storage box. No particulars have been found concerning the operating mechanism of this machine.

J. S. Bloom, Independence, Iowa

J.S. Bloom, Independence, Iowa, developed his ear corn cutter and crusher sometime prior to 1915; by that time, his company was building thousands of them for sale to farmers everywhere. The machine shown here could handle 100 to 250 bushels per hour, probably depending on the stamina of the operator.

Enterprise Engine Works, Independence, Iowa

The concept of the Bloom ear corn cutter and crusher came to J.S. Bloom in 1899, resulting from his efforts to secure more palatable feed for his livestock. By 1915, the company was offering numerous sizes and styles, including this large machine with its own gasoline engine. Curiously, the engine is marked “The Bloom,” but, in fact, it is from Enterprise Engine Works, also in Independence, Iowa.

Appleton Manufacturing Co., Batavia, Ill.

Appleton Manufacturing Co., Batavia, Ill., offered its own version of a corn slicer in its 1917 catalog. This one used a pair of 6-inch knives attached to heavy cast arms. This heavy casting also served as a flywheel. When operated by hand, the cutters made two revolutions to every turn of the crank. Eventually, the need for corn slic-ers faded, as farmers turned to labor-saving grinders that could handle a combination of tasks.

Trade Names

Corn Dryers

World War II is the great dividing line between the old and the new. Many of the time-honored farming practices of the pre-war years were replaced with new ideas and new methods after 1945. Grain farming was becoming more popular; with it came a bad growing season in 1947. This resulted in millions of bushels of soft corn. Storing this high moisture ear corn in large cribs would have been disastrous. Extra air ventilators and many other ideas were used in an effort to save as much of the crop as possible. Thus came the crop dryer, now widely used in most of the corn belt, as well as for other crops.

Peirson-Moore Co., Lexington, Ky

In 1947, Peirson-Moore Co., Lexington, Ky., was one of the firms offering an all-purpose farm dryer. It was equipped with a 5-horsepower electric motor and used a large oil burner for heat. It is shown here, ducted into a steel bin. The warm air was ducted below the grain; as the warm air circulated upward, it carried with it the excess moisture. Within a short time, there were numerous companies offering grain dryers in various sizes and styles. Virtually all grain-dryer designs use propane gas for fuel, although a few operate on alternative fuels.

Corn Graders

Until farmers began using hybrid corn varieties in the 1930s, most farmers used open pollinated corn. When harvesting corn, the best ears were selected and carefully dried for next year’s seed. After shelling, it was also advantageous to grade the corn so that a uniform kernel size was planted in every hill. To that end, many companies manufactured seed-corn graders suitable for every farm. Oftentimes, a group of farmers would buy a grader together, each using it in turn for the new seed crop. Seldom seen today, a corn grader in nice shape will bring $100 or more.

Did You Know?

Ox-yokes sometimes bring $100 or more; excellent examples might bring several times that figure.

Nora Springs Manufacturing Co., Nora Springs, Iowa

Nora Springs Manufacturing Co., Nora Springs, Iowa, advertised its corn graders at the 1908 National Corn Exposition in Omaha, Neb. Shelled corn was fed into the hopper and traveled through a series of revolving screens. Three separate discharge spouts were provided for large, medium and small-sized kernels.

Meadows Manufacturing Co., Meadows, Ill.

Meadows Manufacturing Co., Meadows, Ill., built various farm implements, including elevators and hoists. In 1910, it offered The Improved Peoria seed corn grader, noting that it delivered four different grades of seed; besides that, it was “Indorsed by the State University.” Also of note is the complete lack of guards around the open gears. In those days it was generally presumed that the operator had sense enough to keep fingers and other body parts away from the gears!

Universal Hoist & Manufacturing Co., Cedar Falls, Iowa

More than 40 years ago, the author salvaged a More Corn No. 2 seed corn grader from an attic. It had resided there for many years and was one of many sold in Central Iowa. This machine was made by the Universal Hoist & Manufacturing Co., Cedar Falls, Iowa. The company made an all-out effort to market these corn graders for several years and met with good success. However, the coming of hybrid corn obviated any further need for these machines, so the company entered and left the market within two or three decades.

Trade Names

Corn Harvesters

Corn harvesters are generally considered to be those machines that cut the corn slightly above ground level. Afterward, it was stood up into shocks for curing and later use. Many different companies built corn harvesters, particularly in the late 1880s and into the 1890s. With the coming of the corn binder during the 1890s, this task was mechanized, quickly relegating the corn harvester to obsolescence.

I. Z. Merriam, Whitewater, Wis.

The 1892 advertisement for the Badger Corn Harvester noted that “with it one man can cut and shock from three to five acres of corn in a day.” One can only imagine what it was like using this strap-on device with a knife mounted near the ground. It was offered for sale by I.Z. Merriam, Whitewater, Wis., and was patented under No. 471,881. The patent was granted to James W. Parker at Viola, Ill.

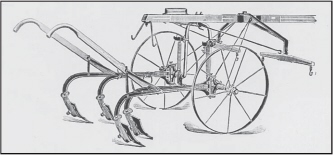

Clipper Plow Co., Defiance, Ohio

Clipper Plow Co., Defiance, Ohio, advertised its Defiance Sulky Corn Cutter in 1889. At the time, this was one of the few corn harvesters built on a wheeled frame. Two men stood back-to-back on the harvester, catching the stalks of corn as they were cut. When enough had been gathered for a bundle, they were tied and dropped in the field. Later, the individual bundles were stood up in a stook or shock, bound into place and remained there to dry.

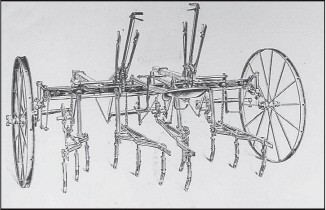

Standard Harrow Co., Utica, N.Y.

Standard Harrow Co., Utica, N.Y., offered its Peterson Corn Harvester to the trade in 1895, continuing with the same machine for several years. The hinged steel wings carried the cutting knives. With both wings down, two rows could be cut at a time; but in case there was only one man available, one wing was folded out of position for a single-row machine. This machine was built under the Peterson patent, No. 443,055 of Dec. 16, 1890.

A. W. Butt Implement Co., Springfield, Ohio

The Daisy Corn Harvester was similar to its contemporaries in that it utilized side-mounted and hinged knives. An 1895 advertisement noted that the machine had already been on the market for six years. The company rated this machine as being capable of cutting eight to 10 acres per day, and a strong sales point was the value of corn fodder as compared to hay, especially when the hay crop was short. This machine was made by the A.W. Butt Implement Co., Springfield, Ohio.

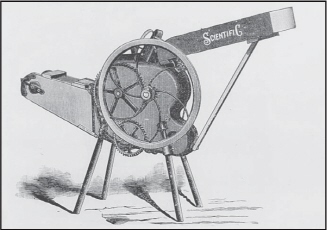

Foos Manufacturing Co., Springfield, Ohio

Licensed by the American Corn Harvester Co., the Foos Scientific Steel Corn Harvester was yet another approach to easy harvesting of standing corn. A substantial seat mounting permitted two men to sit back-to-back while catching the stalks as they were cut. When not in use, the side wings could be folded up out of the way. The Scientific used an all-steel frame, but Foos also offered a wood-frame machine called the Buckeye. Both came from Foos Manufacturing Co., Springfield, Ohio. The machine shown here is from an 1895 advertisement.

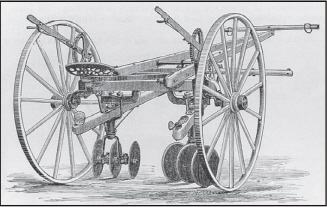

Dain Manufacturing Co., Ottumwa, Iowa

Dain Manufacturing Co., Ottumwa, Iowa, eventually became a part of Deere & Co. Originally established at Carrollton, Mo., this firm came out with many innovative machines, including this all-steel Dain Steel Corn Cutter in 1895. The Dain used a somewhat different design, mounting the cutting knives farther back on the frame than its contemporaries. By 1895, the days of the corn harvester were approaching their end, since the corn binder would mechanize this laborious job.

Superior Hay Stacker Co., Linneus, Mo.

Superior Hay Stacker Co., Linneus, Mo., offered this automatic corn harvester in 1915. It was marketed by Parlin & Orendorff Plow Co., and Rock Island Implement Co., through its branch houses. Advertising of the time indicated that as this machine cut the stalks, theywere held in an upright position and, when a sufficient number were gathered, the bundle of corn could then be removed to a shock or to a wagon, as desired. Outside of this 1915 advertisement, little more is known of the Superior Automatic Corn Harvester.

Eagle Manufacturing Co., Kansas City, Mo.

A specialized device was this Eagle Kaffir Corn Header, offered in 1905 by Eagle Manufacturing Co., Kansas City. At the time, the company claimed that this was “the only machine made that will successfully head and elevate kaffir corn.” As shown here, the device was mounted on the side of a wagon and as it passed alongside the row, the heads were cut and elevated directly to the wagon box.

Trade Names

Corn Huskers & Shredders

Farmers of the 1890s were looking at corn fodder as an alternative to feeding hay. Poor hay crops were always a risk for the livestock farmer; shredded corn fodder was an excellent alternative. Thus came the husker-shredder in the 1890s. The standing corn was harvested just as the leaves started to turn brown or just before full maturity. With favorable fall weather, the corn was placed into shocks for drying and subsequent winter use. Initially, harvesting was achieved with the Corn Harvester by the late 1890s with a corn binder (see previous section on corn binders).

Some companies offered corn shredders with no husker mechanism. A few offered corn huskers that had no shredder. The great majority were combination machines, embodying both mechanisms. The cured corn stalks were fed into the machine where snapping rolls delivered the ear corn one direction and delivered the shredded corn stover in another. Many of these machines, especially the early designs, were extremely dangerous. This was because it was relatively easy for those feeding the shredder to become entangled in the mechanism and be drawn into the snapping rolls. Numerous farmers lost a hand, an arm or even their life while operating one of these machines. Later models were modified so that it was much more difficult to become caught in the mechanism.

Husker-shredders were fairly popular for some years, but were coming to an end in the 1930s. By that time, ensilage cutters were well established and the mechanical corn picker was becoming a reality, rather than a dream.

St. Albans Foundry Co., St. Albans, Vt.

This St. Albans Shredder of 1898 was, as the name implies, strictly a shredder, having no husking attachment. The St. Albans is shown to the left, with the end-product being illustrated as it drops to the floor. St. Albans also produced a smaller unit, The Leslie, shown to the right. It was designed for smaller requirements and required less power to operate. Both were built by St. Albans Foundry Co., St. Albans, Vt.

Crown Point Manufacturing Co. Crown Point, Ind.

Crown Point Manufacturing Co., Crown Point, Ind., announced this combination husker-shredder in 1897. A self-feed mechanism was used, with the manufacturer noting that “there is positively no danger of losing the hands.” The snapped ears of corn dropped to a table below and were carried by elevator to a waiting wagon. The shredded fodder was moved by a large elevator to a stack or to a waiting wagon.

Keystone Manufacturing Co., Sterling, Ill.

Improved for 1895, the Keystone Corn Husker and Fodder Shredder had been on the market for a short time prior to this advertisement. This engraving shows the shredder placed near the barn so that the shredded fodder could be kept dry. Keystone offered this machine in three sizes; No. 1 for threshermen or large farms; No. 2 for medium farms or neighbors and; No. 3 for small farms. It was built by Keystone Manufacturing Co., Sterling, Ill. This firm was eventually purchased by International Harvester Co.

DeSoto Agricultural Implement Manufacturing Co.,DeSoto, Mo.

Manufacturers, large and small, attempted to capitalize on the burgeoning market in husker-shredders. This 1898 advertisement represents the Carrey Perfect Corn Shredder by DeSoto Agricultural Implement Manufacturing Co., DeSoto, Mo. Made in four sizes, the company represented its machines as having greater capacity than any other shredder made. Instead of an elevator for the shredded fodder, this machine used a pneumatic blower.

Safety Shredder Co., New Castle, Ind.

Safety Shredder Co., New Castle, Ind., used a completely automatic feeder to keep the operator’s hands away from the shredder’s mechanism. Its 1903 advertising noted, “No More Loss of Hands!” and, with this machine, to quote its advertising, “You put the corn on the feeder and the machine does the rest.” Undoubtedly, the fear that many farmers had of injury while feeding a shredder was sufficient cause to take a serious look at buying the Safety shredder instead of another make.

E. A. Porter & Brox., Bowling Green, Ky.

Another approach to husker-shredder design was this 1895 model from E.A. Porter & Bros., Bowling Green, Ky. Billed as the Porter Corn Thresher, the engraving here illustrates the method of feeding the corn into the machine, with the fodder emerging from the rear. After snapping the ears from the stalks, this machine shelled the corn, cleaned it and delivered it from a small side elevator.

Rosenthal Corn Husker Co., Milwaukee, Wis.

Rosenthal Corn Husker Co., Milwaukee, was a pioneer firm in this field, having begun with this machine in 1896. It was extremely simple, and the company opted to specialize in husker-shredders. Instead of manufacturing a broad line of implements, Rosenthal made husker-shredders and ensilage cutters for many years.

Rosenthal Corn Husker Co., Milwaukee, Wis.

By 1908, the Rosenthal husker-shredder had taken on a new appearance over the 1896 model. Sold as the Big Cyclone, this machine had great capacity and used a pneumatic stacker to deposit the shredded fodder in a barn or shed. Meanwhile, the ear corn was elevated to a waiting wagon.

Rosenthal Corn Husker Co., Milwaukee, Wis.

Following the evolution of the Rosenthal husker-shredder, this Special 4 machine was offered in 1924. It was smaller and lighter than its ancestors, yet offered great capacity. It also had the advantage of requiring small power; most farm tractors could operate the Special 4. However, by 1930, the husker-shredder was losing in popularity and slowly faded from the scene.

Port Huron Engine & Thresher Co., Port Huron, Mich.

The Port Huron husker-shredder of 1903 was billed as being the only one made with a full-fledged band cutter and feeder. At the time, it was also the only shredder on the market with an all-steel design. Port Huron Engine & Thresher Co., was a major manufacturer of steam-traction engines and threshers and was located in Port Huron, Mich.

Milwaukee Hay Tool Co., Milwaukee, Wis.

Milwaukee Hay Tool Co., Milwaukee, offered this small husker-shredder in 1893. Regarding the husker itself, Milwaukee claimed its machine would husk the smallest nubbins as well as the full-sized ears of corn. This company went on to expand its line of shredders in the following years.

Milwaukee Hay Tool Co., Milwaukee, Wis.

The Milwaukee husker-shredder of 1895 was much more sophisticated than the original 1893 machine. This one had a somewhat larger husking and cleaning section for the ear corn and even included a cleaning screen beneath. Depending on the available power and other conditions, the feeder speed could be varied by the use of interchangeable feed gears. This machine was made by Milwaukee Hay Tool Co., Milwaukee, Wis.

Milwaukee Hay Tool Co., Milwaukee, Wis.

By 1898, the Milwaukee husker-shredder had taken on the same general design, as is shown with this 1904 model. A pneumatic blower was used for the fodder, and the corn husker had been greatly improved. Note the substantial foot board beneath the feeder. With most of these machines it was necessary to feed the stalks into the throat of the husker by hand.

American Shredder Co., Madison, Wis.

American Shredder Co., Madison, Wis., announced this husker-shredder in 1903, having been in the business since before 1880. It was designed with the J.J. Power Automatic Corn Self Feeder. With this system, all danger was removed, as its 1903 advertising noted, “[it] leaves no cripples.”

A. W. Stevens Co., Auburn, N.Y.

The A.W. Stevens Co. announced its new and improved Big 4 corn husker to the 1903 market. Stevens was an old company, first operating at Auburn, N.Y., and later removing to Marinette, Wis. The Stevens machine followed the same general lines as its contemporaries, although this machine shelled the corn and cleaned it.

Janney Manufacturing Co., Ottumwa, Iowa

Janney Manufacturing Co., Ottumwa, Iowa, was an early entrant in the husker-shredder business; shown here is its 1899 model. This was a small hand-fed machine and was distinctive for its all-steel construction. At the time, the majority of these machines were built on a wooden frame and utilized mainly wood construction.

Janney Manufacturing Co., Ottumwa, Iowa

Janney Manufacturing Co., remained in the husker-shredder business for several years, with this 1903 model being substantially larger and more refined than its 1899 version. At this point, the feeder mechanism was much better than before, plus the machine could also shell the snapped corn, clean it and deliver it to a waiting wagon. Oftentimes, shredded corn fodder was referred to as corn hay.

U.S. Wind Engine & Pump Co., Batavia, Ill.

U.S. Wind Engine & Pump Co., Batavia, Ill., offered its U.S. Standard Husker at least into the 1920s. All of its machines built after 1915 could be retrofitted with a special silo-filling attachment. With this system, the corn could be husked and the stalks cut into 1/2-inch pieces for storage in a silo. This company also built husker-shredders. The machine shown here is of 1920 vintage.

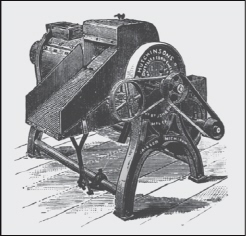

J. I. Case Thresing Machine Co., Racine, Wis.

In 1905, the J.I. Case Threshing Machine Co., offered its Case Husker-Shredder. This machine embodied some of the same features found in its threshing machines and demonstrated the same rugged design. This company, located in Racine, Wis., continued producing husker-shredders until about 1920.

Appleton Manufacturing Co., Batavia, Ill.

Appleton Manufacturing Co., Batavia, Ill., was established in 1872. This company had a long history in the husker-shredder business and refined its 1917 line to include several innovative machines. Shown here is the No. 14 Appleton Corn Snapper. This machine was designed to snap the ears from the stalks, dropping them to the elevator below, meanwhile shredding or cutting the stalks as desired and blowing this material to a stack or into a barn.

Appleton Manufacturing Co., Batavia, Ill.

The Appleton Snapped Corn Husker of 1917 was a stationary machine used only for husking corn that had been snapped by a shredder. In other words, this machine was essentially a husking bed. The husks and debris left via the elevator to the left, while the clean ear corn was carried up the elevator to the right.

Appleton Manufacturing Co., Batavia, Ill.

Appleton’s four-roll corn husker of 1917 was one of several sizes available at the time. This machine used both a cutter head and the shredding saws commonly found on most of these machines. Of all-steel construction, the Appleton was widely sold and used.

Parsons Band Cutter & Self Feeder Co., Newton, Iowa

Success husker-shredders were built by Parsons Band Cutter & Self Feeder Co., Newton, Iowa. Of wooden construction, this machine was available for several years; this particular machine was illustrated in its 1910 catalog. The Success followed many of the design features common to husker-shredders, including the pneumatic stacker that permitted blowing the shredded fodder directly into a barn.

McCormick Harvesting Machine Co., Chicago, Ill.

A 1900 catalog of McCormick Harvesting Machine Co., Chicago, illustrates its husker-shredder in operation. The man at the left is feeding the stalks into the machine, while the two men on the right are getting material up to the feeder. At the rear, another man can be seen stacking the shredded fodder.

International Harvester Co., Chicago, Ill.

International Harvester Co., continued building husker-shredders up to about 1940. However, production had dropped to very low levels. The onset of World War II ended it completely. By the time production ended, these machines were somewhat more sophisticated than their ancestors, including shellers, cleaners and other devices.

New Idea Co., Coldwater, Ohio

New Idea Co., Coldwater, Ohio, offered this six-roll husker shredder in 1927, continuing production for a few years. These machines were usually classed as two-roll, four-roll, six-roll and so on. This indicated the number of snapping rolls in the machine and was a general guide to its capacity.

Advance-Rumely Thresher Co., Kenton, Ohio

Many of the major farm equipment manufacturers offered husker-shredders up to about 1920. Included was the Advance-Rumely Thresher Co., LaPorte, Ind. While each company pronounced its machine to be the best on the market, all of them had good features, along with some that weren’t so good. Much of the final decision rested on product loyalty and for those enamored of the Advance-Rumely line, this machine was undoubtedly their choice.

Daniel Engineering Co., Kenton, Ohio

In 1923, E.H. Daniel, designer of the London Motor Plow, announced plans to build the Mota-Husker. As shown in this photograph, the idea was to husk corn from a standing shock. The husked corn was delivered to a waiting wagon, while the fodder was deposited separately. This machine was built by the Daniel Engineering Co., Kenton, Ohio.

Schuman Corn Handling Machinery Co., Indianapolis, Ind.

One of the most unusual machines associated with the husker-shredder business was the Parsons-Schuman shock loader. With this device, the farmer could mechanically load up to six shocks of corn and bring them to a waiting shredder for processing. This machine was designed in 1909 by the Schuman Corn Handling Machinery Co., Indianapolis. In 1910, Maytag Co., Newton, Iowa, announced the machine under the Parsons-Schuman trade name. Little more is known of it after the 1910 introduction.

Trade Names

Corn Pickers

In the 1930s, the corn picker was finally perfected. With its coming ended the annual “battle of the bangboards,” as well as the “school holiday” while rural kids helped bring in the crop. Beginning about 1900, there were numerous attempts to build and market a corn picker. McCormick even attempted to market one in 1904, but it was not successful.

A 1908 article in Farm Machinery discussed the efforts of Monroe Glick at Metcalf, Ill. He designed a machine that was to pick three rows at a time. Weighing more than two tons, it was equipped with a big 35-horsepower engine. Plans were to dispense with the horses needed to pull the machine, once the mechanism was perfected, leading to a self-propelled corn picker. Despite the publicity at the time, this attempt to build a commercially successful corn picker eluded Glick, as well as thousands of other inventors. Another early corn picker was developed by Appleton Manufacturing Co., Batavia, Ill. The firm brought a machine to the market in 1917, noting that it had been working on its design since about 1904. Like many others that showed some promise by 1917, the Appleton was another that beat a hasty retreat from the market.

International Harvester Co., poured huge sums of money into corn picker development, seeing the corn picker as the last major piece of farm mechanization, outside of the cotton picker. For the company coming out with a machine acceptable to the farmer, there was a huge bonanza waiting to be had. Thus, of all the major companies, International Harvester undoubtedly expended more research and development money than any other. Its work paid off, for, in the 1920s, Harvester made major strides in corn picker development. The company built on its experience derived over various corn picker models built in the 1904-1920 period. Although the early machines eliminated hand picking and did a reasonably good job of plucking the ears from the stalks, they also dropped most of the shucks and some of the stalks into the wagon. Farmers were most unhappy with this prospect, since hand-picked corn was not thus disadvantaged.

Goodhue Manufacturing Co., St. Charles, Ill., made a valiant effort to perfect a corn picker, offering what it considered to be a practical machine in 1908. As with others attempting to achieve this goal, success was elusive. During the 1930s, major strides were made, particularly with the concept of a tractor-mounted corn picker. By the late 1930s, the majority of ear corn was picked by machine instead of by hand. Progress continued apace until temporarily slowed by World War II. After its end, corn picker design renewed itself with a fury, continuing into the 1960s. However, the corn picker, like many other farm machines, had enjoyed its supremacy. The corn combine was on the way.

International Harvester Co., Chicago, Ill.

International Harvester marketed its first corn picker in 1904. It was driven through gearing from a large drive wheel and required four or five horses to pull the machine and operate the mechanism. A wagon was driven alongside the picker to receive the newly harvested corn. One farmer happily reported that he had picked 25 bushels of corn in 23 minutes with this machine. Considering that 100 bushels per day picking by hand was a high average, this was indeed something to gloat about.

Jesse H. Johnson, New Paris, Ohio

In 1906, Jesse H. Johnson of New Paris, Ohio, gained considerable attention with his new corn picker design. This one cut the stalks at the desired height, after which the ears and stalks were fed through combination snapping and husking rolls. Beyond this announcement, little more was heard of the Johnson machine.

Appleton Manufacturing Co., Batavia, Ill.

Appleton Manufacturing Co., Batavia, Ill., began corn picker development as early as 1904. After years of research, this machine appeared in 1917. Weighing more than 3,000 pounds, it was equipped with a ground-drive system for the mechanism, but could also be furnished with an auxiliary engine drive. The company noted that three horses were needed when the engine was used, but for the ground drive it took five horses. The 1917 Appleton could also be furnished with a tractor hitch, if desired.

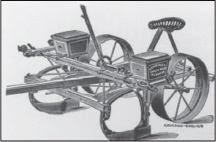

Advance-Rumely Thresher Co., LaPorte, Ind.

Advance-Rumely Thresher Co., LaPorte, Ind., was a well-known engine and thresher builder. It also gained world-wide recognition for the inimitable OilPull tractors. In the 1920s, this firm attempted to build and market a corn picker, a prototype of which is shown here. Beyond this effort, little else is known of Rumely’s venture.

Belle City Manufacturing Co., Racine, Wis.

In 1928, Belle City Manufacturing Co., Racine, Wis., offered its Continental mounted corn picker. With this one-row machine, Belle City claimed that a farmer could pick anywhere from six to 10 acres per day. This machine was moderately successful, with a very few early mounted corn pickers appearing at vintage tractor meets. This one is mounted on a McCormick-Deering tractor, although mounting equipment was available for the Fordson and a few other tractor makes.

John Deere Plow Works, Moline, Ill.

John Deere Plow Co., entered the corn picker market in the 1920s, with this horse-drawn one-row model being available in 1928. It could be operated with ground power, auxiliary engine or from a tractor PTO shaft, as desired. Deere went on to develop an extensive corn picker line, both in pull-type and tractor-mounted models.

Nichols & Shepard Co., Battle Creek, Mich.

Nichols & Shepard advertised its mounted corn picker in 1928, noting that a farmer could pick his corn for a cost of 6 cents to 8 cents per bushel. Like most pickers of the time, it was necessary to synchronize a wagon beneath the corn spout, as the picker made its way through the field. Nichols & Shepard later joined with other partners to form Oliver Farm Equipment Co.

International Harvester Co., Chicago, Ill.

Of all the early corn picker designs, International Harvester was a genuine pioneer. The company had already spent more than a quarter-century searching for a practical corn picker when this pull-type machine came out in 1931. It also had the advantage of an overhead storage tank for dumping directly into a wagon; this eliminated the need for a wagon to come alongside as the picker made its way back and forth through the field.

J. I. Case Co., Racine, Wis.

J.I. Case Co., came along with its new corn harvester, a two-row machine, in 1931. This one was a companion to its one-row model. The Case model was designed for a one-man operation. It utilized a side-mounted wagon hitch, enabling the wagon to travel with the picker.

Wood Bros., Des Moines, Iowa

Wood Bros., at Des Moines, Iowa, attempted to diversify in the 1930s. Prior to that time, it had concentrated on the steam engine and thresher business. Its corn picker of the 1930s was light in weight and included a rear-mounted corn elevator and wagon hitch. Eventually, all corn pickers would follow this idea.

Oliver Farm Equipment Co., Chicago, Ill.

In 1935, Oliver Corp., came out with its Corn Master corn pickers. Undoubtedly, the company built on the ideas pioneered with the earlier Nichols & Shepard corn picker. A major feature was the use of rubber tires and the light weight of the machine; the Oliver Corn Master weighed less than 3,000 pounds.

New Idea Spreader Co., Coldwater, Ohio

In this overhead view, an Allis-Chalmers tractor is coupled to a New Idea picker of the 1930s. While the earliest New Idea design used steel wheels, the company quickly changed over to pneumatic tires to lessen the draft. The overhead view illustrates the unique side-hitch used by New Idea. A simple chain attachment was hooked to the wagon tongue. It engaged a dog in the side-hitch. Through a control rope, the operator could shift the wagon forward or back, relative to the spout, thus filling the wagon from front to back without leaving the driver’s seat.

New Idea Spreader Co., Coldwater, Ohio

This 1941 illustration shows the New Idea one-row model. This one used a rear-mounted elevator and embodied many features that remained in the New Idea corn picker line throughout a long production run. While some farmers preferred the one-row design, the vast majority opted for a two-row picker.

McGrath Manufacturing Co., Omaha, Neb.

The Sargent corn harvester was a fully mounted machine that emerged in 1947. With this unique design, the stalk was cut at the ground and cutting continued until the ear was cut from the stalk. Sargent even equipped this machine with a removable husking bed for picking sweet corn. It was built by McGrath Manufacturing Co., Omaha, Neb.

Trade Names

Corn Planters

Corn cultivation has been pursued for centuries. Until the late 19th century, corn was planted with a hoe, with seeds being dropped into each hill by hand. This was a very laborious task and thousands of inventors were at work trying to perfect a machine that would plant corn. To cultivate the crop, it was planted in rows; during the 1850s, the idea of planting in check rows developed (the field could be cultivated lengthwise and crosswise to minimize weed infestations).

A few planters appeared in the 1840s, but, in the 1850s, real progress appeared. The George W. Brown patent (No. 9893) of 1853 was the first major development in corn planters. Brown set up a factory at Galesburg, Ill., and began building his new invention. This was the first planter to use runners to open the furrow and press wheels to firm the seed in the row. To plant the seed in check rows, it was first necessary to mark the field. This was achieved with a specially built marker that was pulled across the field, first lengthwise and then crosswise to mark the exact location for each hill of corn. The planter had two seats, one for the driver and one for the dropper. The latter operated a hand-lever each time he reached the intersection of the lines. Corn planters continued to be built under this pattern for a number of years, although there were many attempts to build an automatic check-row planter.

Guide markers first appeared in the late 1850s. Galt &Tracy, later Keystone Manufacturing Co., Sterling, Ill., made major improvements, introducing the open-heel runner, which permitted the kernels to drop inside the open heel, after which they were covered. Deere & Mansur were instrumental in developing the rotary-drop system, using rotating plates in the bottom of the seed canisters. Numerous other developments came along, but there still was not a successful automatic check-row planter.

Already, in the 1850s, attempts were made to check automatically, using a chain with buttons spaced periodically. Others attempted using rope with knots at the appropriate spacing, but none of these plans were entirely satisfactory. The initial success with a check-row planter is generally ascribed to G.D. Haworth. During the 1870s, Haworth made considerable progress, and, with the development of steel wire suitable for the purpose, the check-row planter became a reality. Once this happened, improvements were needed in the dropping mechanism, and this led to the development of the rotary-drop design.

The author’s first inclination was to arrange the development of the corn planter in some sort of chronological order. This created a major problem in maintaining the developmental continuity of several manufacturers, so these machines are arranged alphabetically, by company.

Of further interest, some of the early corn planters, especially those prior to the automatic check-row designs, are essentially museum pieces. If available, they can command $500 or perhaps much more. Later models, particularly those after 1930, often have little value. In this same connection, the cast-iron lids from the seed boxes have now become a rarity. Depending on the scarcity of a certain style, these can be valuable but, on average, bring $20 to $30 in good condition.

American Seeding Machine Co., Springfield, Ohio

This Evans Simplex corn planter of 1903 was equipped with disc openers instead of the usual planter runners. A.C. Evans Manufacturing Co., Springfield had long been established with its Buckeye grain drills and other farm implements. In 1903, Evans joined with several other firms to incorporate the American Seeding Machine Co., headquartered at Springfield, but maintaining the factories of most partners to the reorganized firm.

Avery Planter Co., Galesburg, Ill.

Avery Planter Co., was organized at Galesburg, Ill., in 1874. Robert Avery had developed some ideas about corn planters in the 1860s, an example of which is shown here. Eventually, he and his brother Cyrus M. Avery organized a company to manufacture the planters. In 1884, the company relocated to Peoria,Ill., all the while expanding its implement line. In 1891, the company began building steam engines and threshing machines. Eventually, the company opted for this endeavor, gradually going out of the implement business.

Avery Planter Co., Peoria, Ill.

From its humble beginnings in the corn planter business, Avery eventually grew to be an industry leader, manufacturing engines, tractors, and threshers. By the early 1920s, through difficulties not entirely of its own, Avery essentially was bankrupt. Reorganized as Avery Power Machinery Co., it never again rose to prominence due to market saturation, overproduction, and a failure to develop new machines to meet with ever-changing power farming requirements.

By 1899, Avery Co. had developed its Corn King and Corn Queen planters; the latter style is shown here. By this time, the company offered several different types of furrow openers as well as other options. For instance, the press wheels could be flat, concave or open design, as desired. Avery continued to build this planter at least until about 1910.

In 1908, Avery Co. announced its new Perfection planter. Options included three styles of press wheels and pointed, sled or disc runners. The Avery Perfection used an automatic self-lift device and the guide markers were automatic in their operation. By 1912, Avery was opting out of the farm implement market in favor of its growing tractor and thresher business.

B.F. Avery & Sons, Louisville, Ky.

B.F. Avery began making plows at Louisville in 1845. The company grew and diversified, but we have established no precise date for the introduction of the Avery corn planters. Its 1916 line included the Avery Sure Drop planter, an all-steel unit that was ordinarily furnished with open press wheels as show. Like other planters of the period, this one featured an adjustable row width for various crop requirements.

The Avery Plainsman lister of 1916 was but one item in the extensive B.F. Avery line. The lister or lister-planter was developed about 1880, with most of the credit going to William Parlin of Parlin & Orendorff Co., Canton, Ill. From his efforts, came the majority of lister design as used for many years to follow. However, each manufacturer had its own designs and the Avery, like the others, had its own salient features. This company had no connection or relation to Avery Co., Peoria, Ill.

Beedle & Kelly Co., Troy, Ohio

By the 1880s, there were literally hundreds of companies attempting to build corn planters. Due to the great demand, there was room for everyone for a time, but as the market became saturated, many of the smaller firms were forced out of business. One small firm was Beedle & Kelly Co., Troy, Ohio. Shown here is its 1898 version of the ideal corn planter. Except for this advertisement, little else is known of the firm.

Belcher & Taylor Agricultural Tool Co., Chicopee Falls, Mass.

In 1903, Belcher & Taylor advertised this Eclipse Two-Row Two-Horse Corn Planter, claiming it to have all the good features of the Eclipse one-row model. Also included was a dry fertilizer attachment; it banded soil nutrients either into or beside the row. This firm was a well-known manufacturer of farm implements for many years.

Briggs & Enoch Manufacturing Co., Rockford, Ill.

Virtually nothing is known of Briggs & Enoch outside of this 1898 advertisement for its Rockford corn planter. Although this planter is obviously equipped as an automatic check-row machine, it also appears that it could be operated as formerly, using a separate person to work the valve lever and drop the corn into the row manually.

Anyone having additional materials

and resources relating to American

farm implements is invited to contact

C.H. Wendel, in care of Krause

Publications, 700 E. State St.,

Iola, WI 54990-0001.

Geo. W. Brown & Co., Galesburg, Ill.