E

Earth Moving Equipment

Like the Ditching Machines section previous, earth-moving equipment is not technically related to the farm machinery business. Yet, numerous kinds of earth-moving devices made their way to the farm. Early on, it was the drag scraper or the fresno; with the coming of tractor power came all kinds of devices intended to move small quantities of dirt on the farm.

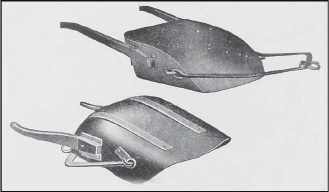

One of the most popular methods of moving dirt for the small farm was with a drag scraper, sometimes called a slip scraper. Pulled with a team, the slip scraper could be filled with relative ease; when pulled to the final location, the operator raised the handles to upset the load.

Another style of scraper was the Fresno or Buck Scraper. This one was somewhat larger than the slip scraper and was available in sizes up to 5-feet wide from P&O Plow Co., Canton, Ill. Some companies also made wheeled Fresno scrapers as yet another alternative.

Did You Know?

Today, small grain seeders, especially the wheelbarrow and “knapsack” seeders, have attained an antique value, often selling for more than $200, depending on condition.

The Albrecht Excavator was a curious machine announced in 1913. It was developed by John Albrecht of Madison, Wis. B.B. Clarke, founder of American Thresherman magazine was financially interested and closed a deal with Avery Co., Peoria, Ill., to build and market the machine. The slip scraper dumped into a hopper and the latter then dropped the load of dirt onto a waiting wagon. Little more is known of this design, outside of a 1913 announcement.

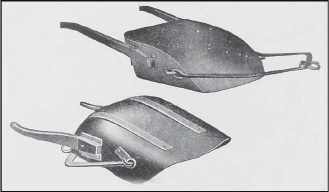

Popular during the 1930-1950 period was the Groundhog Scraper, also known as a “tumblebug.” This simple little scraper was pulled by a tractor and is shown here in the loading position. When the load arrived at its destination, pulling a trip rope permitted the entire scraper box to revolve, discharging the load. This one was built by Roderick Lean Manufacturing Co., and later by Farm Tools, Inc.

Another style of rotary scraper was the K-S model built by Central Manufacturing Co., Omaha, Neb. A 1946 advertisement noted that this machine was again available; undoubtedly, production had been halted because of World War II. Eventually, the rotary scraper or tumblebug, was supplanted by other designs. After World War II, many styles of tractor-mounted scrapers and dozers appeared.

Elevators

Portable elevators and wagon dumps started gaining popularity in the 1890s. By 1905, several companies were building elevators, particularly in Illinois. The notion that ear corn and small grains had to be shoveled by hand quickly came to an end when the first elevator appeared in the neighborhood. While the farmer stood and watched the corn going into the crib with very little work on his part, envious neighbors soon made a trip to town and got one of their own. Numerous companies have built grain elevators over the years, but constraints of space have limited this section to a few of the notable examples.

Camp Bros., & Co., Metamora, Ill.

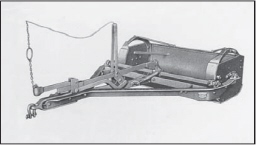

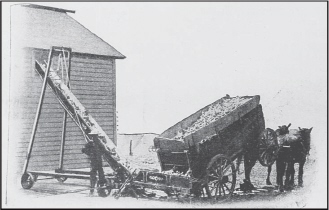

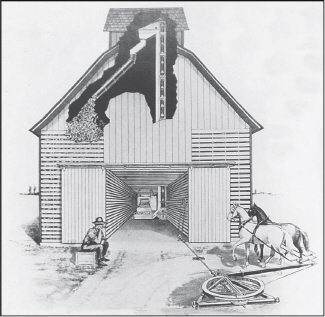

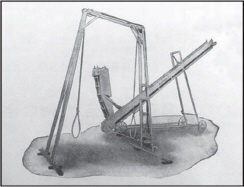

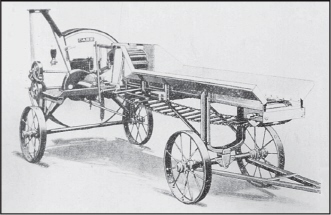

Among early trade journals, Camp Bros., was generally accepted as the first company to offer a portable elevator to the farmer. By mounting it on wheels, a single elevator could fill any number of cribs. This 1907 model is shown with a wagon dump, also made by Camp Bros. This eliminated much of the hard work for the farmer.

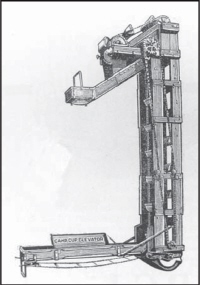

By 1915, Camp Bros. was offering a stationary cup elevator. It was intended for built-in use in a large crib. By this time, many cribs were also built with overhead grain storage for oats and other small grains. The Camp elevator could handle any of these jobs with ease.

Deere & Co., Moline, Ill.

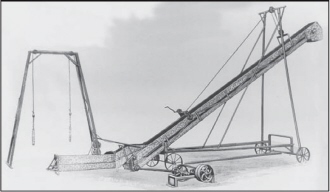

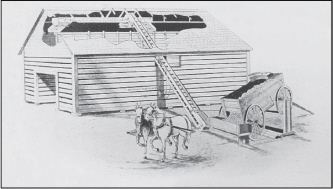

A typical John Deere elevator set-up might have included the various items shown here. A small sweep power operates the elevator and the wagon dump. To avoid an excessively long elevator, a secondary elevator was used to carry grain to the cupola of the crib. From there, distributor spouts could deliver the crop wherever wanted. Deere continued manufacturing grain elevators for many years.

J.A. Engel & Co., Peoria, Ill.

No elevator set-up would have been complete without an automatic grain dump. Virtually all of these consisted of a mechanism to raise the front of the wagon, allowing the grain to exit by gravity. Engel’s Ideal elevator was one of the earliest on the market, but, for reasons unknown, the company quickly blends into obscurity.

Kewanee Machinery & Conveyor Co., Kewanee, Ill.

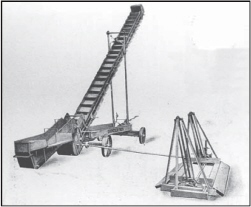

This Kewanee Outfit No. 126 of the 1920s included a 26-foot elevator, hopper and the wagon dump or derrick, plus a speed jack to run everything at the proper speed. By this time, Kewanee was prepared to offer its all-steel design in sizes anywhere from 20 to 50 feet.

Kewanee was a major manufacturer of indoor or stationary elevators. These were usually built-to-order for each corn crib, shipped from the company and assembled on-site by a competent machine man. Once erected, many of these elevators operated for decades with little or no attention to repairs or replacement parts.

King & Hamilton Co., Ottawa, Ill.

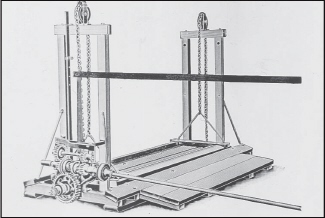

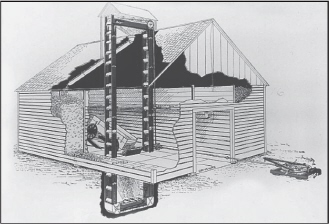

By the 1920s, King & Hamilton had become a leading manufacturer of stationary cup elevators. A cutaway view of this large corn crib illustrates how the loaded wagon was driven over the dump, trussed to the lift chains and unloaded with almost no effort on the part of the farmer.

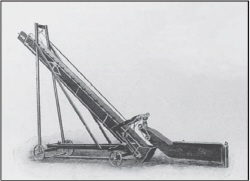

King & Hamilton excelled with its indoor cup elevators and also built an extensive line of portable elevators (as shown). This one was of all-steel design, although there were numerous makes still using wood for at least part of the construction.

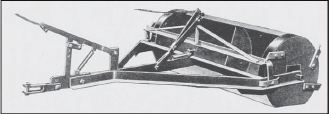

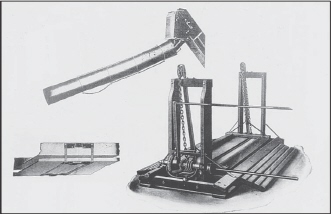

A close-up view shows the American Dump, as built by King & Hamilton. The wagon was driven over the dump with the front wheels resting between the bottom irons. A simple gear clutch mechanism raised the wagon. The American was but one of probably hundreds of different designs. With the coming of tractor hydraulics and self-contained hydraulic wagon hoists, mechanically operated wagon dumps soon came to an end.

Luthy & Co., Peoria, Ill.

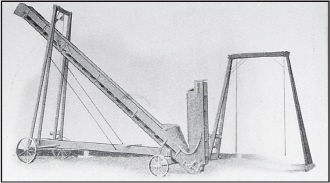

The Ideal elevator, as made by Luthy & Co., is shown in a 1908 magazine illustration. This one was an all-wood design, even the wagon derrick is made of wood. Since many grain elevators spent their lives outdoors, wooden construction was undesirable because of its short life when exposed to the elements.

Maroa Manufacturing Co., Maroa, Ill.

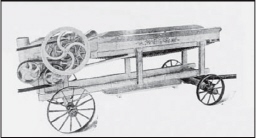

Little is known of Maroa Manufacturing, except for this 1908 illustration of its elevator. Various trade directories do not list this company by 1914. Perhaps the company sold out to another; the firm went into another endeavor; or, equally possible, it simply went out of business.

Marseilles Manufacturing Co., Marseilles, Ill.

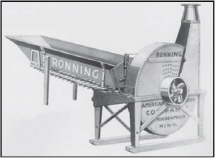

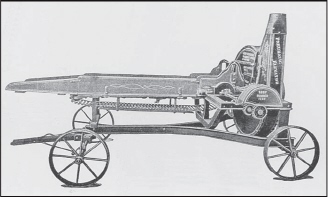

Undoubtedly, the Marseilles elevator line was a major influence on the Deere elevator line; the latter bought out Marseilles in 1911. Shown here is a 1907 example of the Marseilles elevator; its heavy construction endeared it to many farmers.

Meadows Manufacturing Co., Pontiac, Ill.

In 1906, Meadows advertised its Improved Rocke grain elevators, small and light-weight when compared to many competing designs. The success of this small elevator led the company into a full-fledged business and an excellent reputation in the grain elevator business.

Following the Improved Rocke design, Meadows built this impressive all-wood elevator at least into the 1920s. It was available in sizes from 24 to 50 feet. Operating at its rated speed, the manufacturer claimed it could move 40 bushels of corn per minute from wagon to crib.

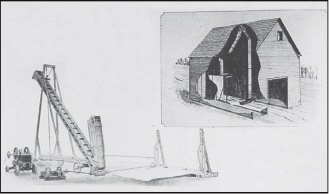

Meadows was offering an extensive line of portable and stationary grain elevators by 1912. As shown here, the elevator could be operated by a gasoline engine or with a small sweep power. To the right is shown a cutaway of an inside crib design; Meadows marketed thousands of these elevators. Sometime during the 1930s, Meadows became a part of Farm Tools, Inc., gradually disappearing from the scene.

A.F. Meyers Manufacturing Co., Morton, Ill.

By 1915, Meyers was offering its inside elevators to the market. The Meyers design shown here was typical for the period; in fact, this design changed little for many years. The elevator cups traveled along the bottom of the hopper, carrying their load of grain, dropping it off at the top and returning for another load. The Meyers was extremely popular and thousands of them were sold, with many still in use.

O’Neil Implement Co., Marseilles, Ill.

From about 1910 comes this illustration of the O’Neil grain elevator. This was an all-steel design that included an optional gasoline engine; it appears to be a Sandow two-cycle model from Detroit Motor Car Supply Co., Detroit. Presumably the O’Neil elevator line was available in varying lengths; the style shown here is probably a demonstrator model used for fairs and dealer exhibits.

Portable Elevator Manufacturing Co., Bloomington, Ill.

By 1908, The Little Giant elevators were available with a traveling cross conveyor as shown. With this unit permanently mounted beneath the crib roof, it was possible to elevate grain to any position within the structure.

The Little Giant Wagon Dump of 1909 was essentially the same unit as the company continued to make for decades. It was a very simple design, connected to the elevator with a tumbling shaft. Some farmers placed wooden guards over the tumbling shafts. Others didn’t and many communities reported instances of farmers getting their pant legs caught in the rotating shaft, sometimes with injury.

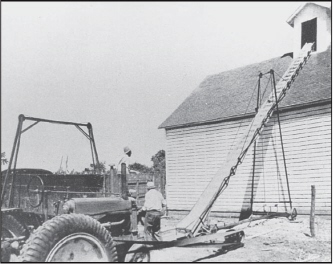

Little Giant portable elevators of 1940 were of the latest all-steel design; this one is 46-feet long and a spare tractor is used to operate the speed jack. Oftentimes, a small gasoline engine was used. For those fortunate enough to have “high line” electricity by 1940, an electric motor became a reality.

Rumely Products Co., La Porte, Ind.

In 1913, Rumely announced its inclusion of the Swanson elevators into its product line. Apparently, it was the product of Swanson-St. Joseph Plow Co., St. Joseph, Mo. Outside of a few advertisements, little more is known of this excursion of Rumely into the farm elevator business.

Sandwich Manufacturing Co., Sandwich, Ill.

A 1908 advertisement for the Sandwich elevator notes that “a few were sold in 1906, hundreds in 1907 and twice as many will be sold in 1908 as in this past season.” The Sandwich farm machinery line was very popular, so its portable grain elevators gained rapid acceptance and considerable sales.

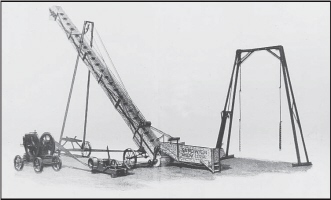

In the early 1930s, Sandwich Manufacturing Co. was bought out by New Idea Spreader Co., Coldwater, Ohio. The latter continued to market the Sandwich-New Idea line for several years. One example is this all-steel elevator, complete with speed jack, wagon dump and a Sandwich gasoline engine. Eventually, New Idea redesigned the elevators, continuing to market its own designs for decades after.

Schroeder Bros., Minier, Ill.

For reasons unknown, construction of portable and stationary grain elevators was centered in Illinois for decades. One example is the Schroeder elevator, shown here in a 1907 advertisement. This one was of all-wood construction, still preferred by many farmers and manufacturers over the “new-fangled” all-steel designs.

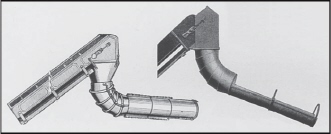

Once the grain or corn was elevated to the top of the crib, it was necessary to distribute it where it was wanted. To this end, most companies offered flexible spouts of various designs. Beyond this, companies like Baier Bros., Manufacturing Co., Cissna Park, Ill., offered a flexible spout that could be fitted to any elevator; it is shown on the left of this illustration. On the right is a flexible Schroeder spout made by Schroeder Bros.

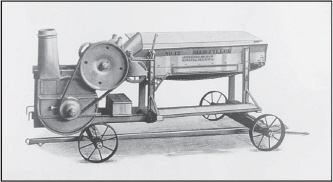

Trade Names

Engines

While the reaper, the plow, the threshing machine and many other implements served to mechanize agriculture, the gasoline engine also had a dramatic effect on mechanization. With the introduction of the Otto Silent gas engine in 1876 came virtually all of today’s internal combustion engines.

The heavy stationary engines that began to appear from 1900 onward soon made their way to almost every farm. By the thousands they made their way from factories to the wash house, the corn crib and the granary. We would be remiss in not making mention of the gasoline engine, but it has been covered extensively in our book American Gas Engines Since 1872 (Crestline/Motorbooks: 1983). Its 584 pages represent the most comprehensive pictorial history ever published on gas and gasoline engines. Thus, we felt that to include engines in this book would only serve to exclude other significant developments in the farm equipment scene. Occasional references are made within this book to the gas engine, but for detailed information, the reader is referred to the above title.

Ensilage Cutters

Ensilage, that is, the process of putting a crop into a silo for storage, didn’t begin in the United States until the late 1870s. At first, it was thought necessary to fill the silo then weight it down with stones, earth or whatever was available. In a short time, it was discovered that the weight of the material itself was enough to exclude the air, so that spoilage occurred only on the top. By the 1880s, ensilage was becoming a popular method of feed storage, especially with standing corn.

Prior to the coming of ensilage and ensilage cutters, numerous companies made feed cutters and/or fodder cutters. For a time, there were combination feed cutters/ensilage cutters. A few even tied back to the corn husker-shredder. Thus the reader is advised to look in the various sections of this book for relevant items, especially under Feed & Fodder Cutters, Corn Husker-Shredders, Feed Mills and Grinding Mills.

Ensilage cutters were very popular and there were a few in almost every farming community, most of them being owned by a group of farmers or perhaps by one or two farmers, who then filled silos on a custom basis. These machines maintained their popularity into the 1940s, but the coming of the field harvester brought a quick end to these machines, along with the corn binder. With the field harvester or field cutter, a farmer could cut and chop the corn or hay and blow it into a towed wagon. When full, the wagon went to the silo, its automatic unloading system was engaged and the material went via a blower into the silo. This system still prevails today.

Advance-Rumely Thresher Co., LaPorte, Ind.

Rumely was offering ensilage cutters as early as 1912; in 1923, it announced this new No. 16 Silo Filler. It was a flywheel cutter, meaning that the cutter knives were mounted on what were also the fan blades to convey the cut material into the silo. The stalks of corn were fed onto the conveyor table by hand.

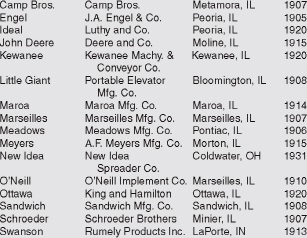

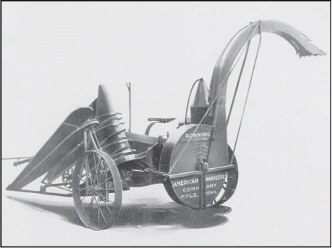

American Harvester Co., Minneapolis, Minn.

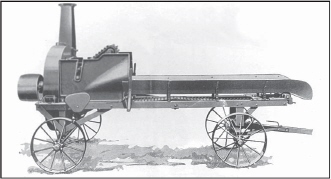

Heralding a revolutionary change, the Ronning field harvester was developed in the 1920s. It used an engine of 15 or 20 horsepower, mounted directly on the machine. A tractor towed the cutter through the field, delivering ensilage into a wagon alongside. Despite its obvious advantages, it took some years before the Ronning gained real success.

American Harvester also offered this semi-portable ensilage cutter, noting that it was the only one on the market that could be converted to a field harvester. The idea was that a farmer could buy this unit one year and buy the remaining parts a year or two later to make the conversion to a full-fledged field cutter.

Appleton Manufacturing Co., Batavia, Ill.

Appleton had its No. 12D Silo Filler (pictured here) on the market by 1917. Depending on the wishes of the farmer, most cutters could be set for a cut of 5/16- to 2-1/2 inches. Ordinarily, it would be set somewhere between 1/2-inch and 1-inch. Many thresher-men owned an ensilage cutter or silo filler; this gave them extra autumn work after the threshing season was past.

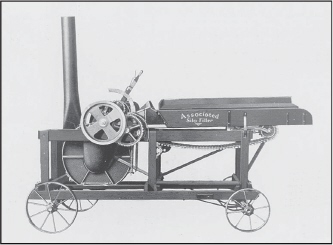

Associated Manufacturers, Waterloo, Iowa

In the 1910-20 period, the demand for ensilage cutters was stronger than at any other time. Up to 1910, many farmers had yet to be convinced of the need for a silo. In the decade that followed, the demand for silos and silo fillers was insatiable. Shown here is an Associated Silo Filler of 1917.

Avery Co., Peoria, Ill.

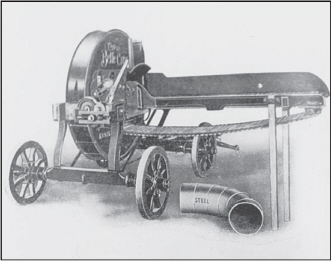

For a time in the early 1920s, Avery offered its version of the silo filler. Like most machines, it was a flywheel cutter, with the knives mounted together with the fan blades on a single hub. Since it was necessary to keep the knives sharp, a special grinding attachment was usually built integral with the machine.

Belcher & Taylor Agricultural Works, Chicopee Falls, Mass.

As pointed out in the introduction to this section, some companies advertised a combination ensilage and fodder cutter, precisely as advertised in this 1903 machine from Belcher & Taylor. Before pneumatic blowers came into general use, a few enterprising companies used an elevator to carry the cut material into the silo.

Belle City Manufacturing Co., Racine, Wisc.

By 1908, Belle City was offering several different styles of ensilage cutters, with its A-2 model shown here. This one weighed about 1,600 pounds on the four-wheel trucks; the latter was an option, if it was desired to have a stationary machine.

J.I. Case Co., Racine, Wisc.

J.I. Case introduced this Model B silo filler to the market in 1928. It was a flywheel cutter design, similar to others on the market. About this same time, J.I. Case began to greatly expand its product line; by the 1930s, Case offered one of the largest implement lines in the entire industry.

Joseph Dick Co., Canton, Ohio

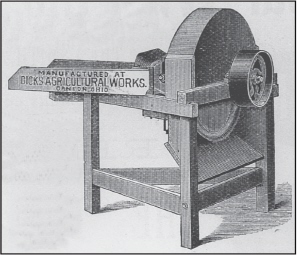

In 1887, Dick’s Agricultural Works offered its Famous Patent Feed Cutter, noting that it was “for hay, straw, corn stalks and ensilage. Adapted for hand, horse, steam or wind power.” At the time, the terms “silo filler” and “ensilage cutter” hadn’t yet come into vogue; in reality, they all meant the same thing as the term “feed cutter.”

By the 1920s, Joseph Dick Co., had become a well established manufacturer of ensilage cutters. Shown here is its No. 400 machine; the company had sometime previously adopted the “Blizzard” trade name to its cutters. At some point, apparently in the 1930s, the company took the name of Blizzard Manufacturing Co.

Eagle Manufacturing Co., Appleton, Wisc.

Eagle Manufacturing Co. was an important source for ensilage cutters, feed grinders, gasoline engines, tractors and other equipment. Shown here is its 1907 model of the Eagle Self-Feed Ensilage and Fodder Cutter. Note that even at this time Eagle was speaking of a combination “ensilage and fodder” machine; the line of separation was indeed still present, but was slowly fading.

Farmers Manufacturing Co., Sebring, Ohio

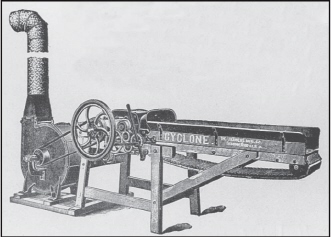

In 1903, Farmers Manufacturing Co., offered its Cyclone Blowers and Carriers, along with its own feed or ensilage cutters. These were optional attachments; the plain machine simply dropped the cut material on the ground. Likewise, the semi-automatic feeder was an option that eliminated the tedium of feeding two or three stalks of corn at a time.

Gehl Bros., Manufacturing Co., West Bend, Wisc.

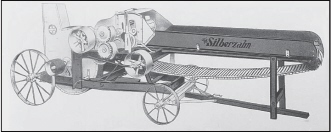

By 1912, Gehl was offering this style of the Silberzahn ensilage cutter. It was very popular, particularly in its native state of Wisconsin, as well as in other regions. This 1912 advertisement notes that “Our business is growing wonderfully in the West.” Obviously the company was making sales inroads into various areas.

The Silberzahn ensilage cutter from Gehl Bros. took on an entirely new look by 1916. Here was an all-steel design that was fully portable. The cutter head was of the “lawn-mower” type—that is, the knives were mounted on a revolving drum. The cut material then dropped into a separate blower; in turn, it lifted the silage into the silo. Gehl was a pioneer in building field harvesters and was very successful in this endeavor.

W.R. Harrison & Co., Massillon, Ohio

By 1905, Harrison was offering its Celebrated Tornado Feed and Ensilage Cutter. The optional blower was named the “Tornado Pneumatic Elevator.” Harrison also builds silos, steel field rollers, corn shellers and wheelbarrows. The company is listed as late as 1931; by 1939, repairs only could be secured from Massillon Bolt & Rivet Co., Massillon, Ohio.

Hocking Valley Manufacturing Co., Lancaster, Ohio

Hocking Valley was a well-known firm that made corn shellers, feed cutters and other farm machines. Shown here is its No. 13 Feed Cutter. While this one was hand-fed and dropped the cut material out of a bottom chute, it probably could have been adapted to various attachments, if desired. This model is shown in a 1904 catalog.

Did You Know?

An ancient box or barrel churn can bring $500 or more on the antique market.

International Harvester Co., Chicago, Ill.

The International Type A ensilage cutter was built from 1912 to 1940. During that time, thousands of these immensely popular cutters were manufactured. The company built many other styles through the years, even selling the Belle City ensilage cutter line up to about 1917.

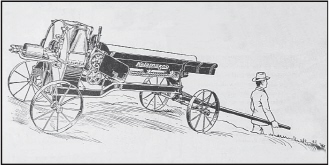

Kalamazoo Tank & Silo Co., Kalamazoo, Mich.

For 1920, Kalamazoo offered this all-steel machine. While no details of the company’s origins have been found, it appears that the Kalamazoo ensilage cutter was available at least into the late 1930s. Parts were available at least into the late 1940s.

Maytag Co., Newton, Iowa

Today, Maytag Co. is best known for its home appliances. For many years, though, the company was an important manufacturer of farm machinery. Its 1914 offering included the Iowa Ensilage Cutter, an impressive machine with a large feed table and a heavy hard-maple frame. Eventually, Maytag opted out of the farm equipment business to build its washing machines and became a leader in that industry.

Papec Machine Co., Shortsville, N.Y.

When this 1905 advertisement appeared, Papec was located in Lima in Livingston County, N.Y. Subsequently, the company moved to Shortsville, operating there for many years. The Model D cutter shown here was claimed to be “The Strongest and best Ensilage Cutter on earth.” Undoubtedly, this machine had some excellent qualities, since the Papec machines were very popular.

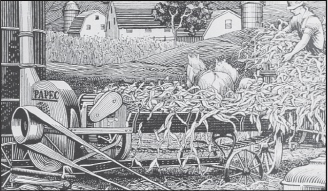

Pictured here is a 1927 scene depicting a farmer feeding stalks of corn into a Papec cutter. In reality, it usually demanded one person to stand by the feeder and help things along, all the while keeping those on the wagon from feeding in too much corn and plugging the machine from stem to stern.

A 1931 photograph illustrates a Papec ensilage cutter chopping dry hay and blowing it into a barn. An unusual feature was the installation of a large electric motor on the cutter; only those near a major power line could take advantage of this power source. Coincidentally, dry chopped hay was especially prone to spontaneous combustion, causing many barn fires as a result.

Plymouth Foundry & Machine Co., Plymouth, Wisc.

By 1915, the Plymouth Self-Feed Cutter had become very popular; in fact, Fairbanks, Morse & Co., had become distributing agents for the Plymouth line. At the time, Fairbanks-Morse was expanding greatly into the farm machinery market, although it withdrew somewhat in the 1920s. Plymouth is listed as a manufacturer at least into the late 1950s.

Rosenthal Corn Husker Co., Milwaukee, Wisc.

Rosenthal is perhaps best known for its corn huskers and shredders. By the 1920s, the company was offering a series of ensilage cutters. Included was its Big 21 Ensilage Cutter and Silo Filler. The company claimed it could cut and deliver anywhere from 15 to 30 tons of silage per hour. To do so required a sizable labor force, just to get the loads of corn up to the machine.

E.W. Ross Co., Springfield, Ohio

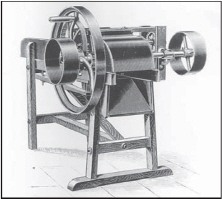

Ross was an early entrant in the feed cutter business, offering this Little Giant No. 11A feed cutter in 1887. As can be noted here, this cutter could be run by belt power, but could also be operated by hand-crank if necessary. The entire unit was built of heavy wood and ample iron castings.

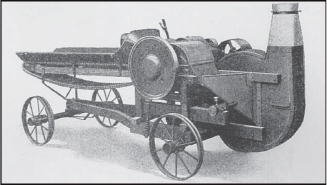

For 1910, Ross was offering this feed cutter, although it had the blower for elevating the cut feed into a silo. As noted elsewhere, some companies preferred the title of “feed cutter,” some used “ensilage cutter,” and others preferred “silo filler.” Parts for these machines were available as late as the 1940s from Ross Equipment Co.

I.B. Rowell Co., Waukesha, Wisc.

Rowell offered its Safety-Automatic ensilage cutter to the trade in the 1920s. Outside of a single 1920 advertisement, little is known of company activities, but the company is still listed as a manufacturer of ensilage cutters as late as 1948.

St. Albans Foundry Co., St. Albans, Vt.

In 1895, St. Albans was building this rather large corn fodder shredder; it did not have a husker, but shredded everything fed into it. An elevator carried the shredded material to a waiting wagon or perhaps a bin. For corn that had cured in a shock, the shredder was a better choice than a feed cutter. Mansur & Teb-betts Implement Co., St. Louis, was a distributor for the St. Albans line. St. Albans began building fodder shredders already in 1883.

Silver Manufacturing Co., Salem, Ohio

An 1895 offering was the Ohio Standard Ensilage and Feed Cutter from Silver Manufacturing Co. The machine shown here was offered in four different sizes, this one being the No. 18. Silver also was building numerous other styles and sizes of cutters at the time. The company is listed as a manufacturer at least into the late 1940s.

Smalley Manufacturing Co., Manitowoc, Wisc.

In 1904, Smalley offered its Modern Silo Filler, with this one being the New Smalley Special 18 model. The blower was mounted down low, so as to pick up the cut material from the knives. To effectuate this design, a right-angle gear drive operated the blower shaft. This required an unusual belting arrangement.

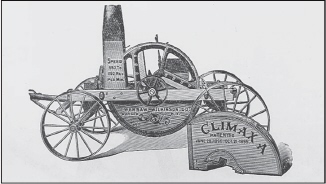

Warsaw-Wilkinson Co., Warsaw, N.Y.

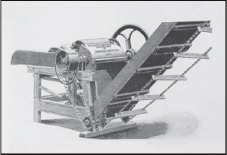

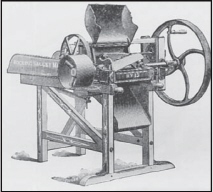

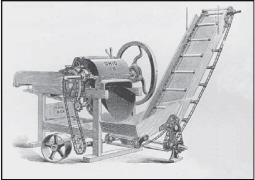

An early entrant into the ensilage cutter business was the Climax from Warsaw-Wilkinson. This one was offered in three sizes: the smallest one selling for $190 and the big 23-inch model selling for $225. This price included a mounted self-feed table. With the cover removed, the cutter knives are plainly visible on the flywheel.

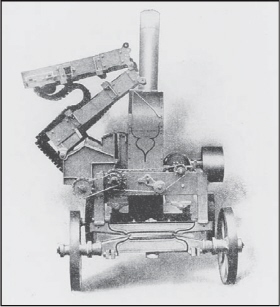

Wilder-Strong Implement Co., Monroe, Wisc.

This model of Wilder’s Whirlwind was offered in 1905. It was billed as a feed cutter or fodder cutter, but the head-on view shown here offers little in the way of description. Obvious, though, is the unique folding feed carrier that permitted easy moving from one farm to another. Virtually no information has been located on this firm.

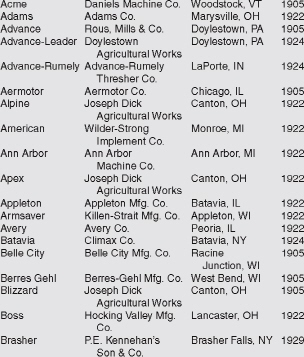

Trade Names

Anyone having additional

materials and resources

relating to American farm

implements is invited to contact

C.H. Wendel, in care of Krause

Publications, 700 E. State St.,

Iola, WI 54990-0001.