Wagons

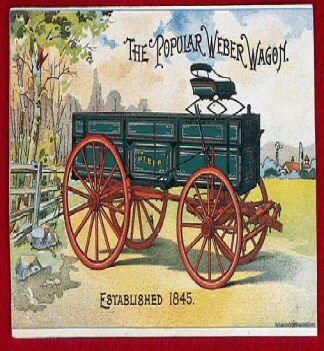

IHC acquired this company in 1904. Weber had been an established wagon builder for some years prior to this time. Weber Wagon Co., Chicago, Ill.

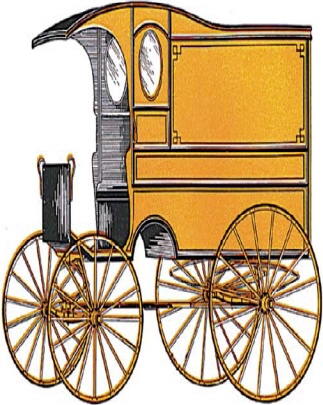

This famous automobile maker started business making wagons and carriages. Shown here is its Village Market Wagon. Studebaker Bros. Mfg. Co., South Bend, Ind.

While Studebaker is probably better known for its fine carriages, the company also built high-quality farm wagons. Shown here is a fine example from about 1900. Studebaker Bros. Mfg. Co., South Bend, Ind.

Many companies built wagons on a more-or-less localized basis. This company had various kinds of dirt scrapers as its main line, eventually dropping wagons altogether. Western Wheel Scraper Co., Mt. Pleasant, Iowa.

Northwestern Mfg. Company, Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin

This attractive wagon was offered in sizes 3 x 9, 3 1/4 x 10, and 3 1/2 x 11 feet. These figures refere to the inside demensions of the box.

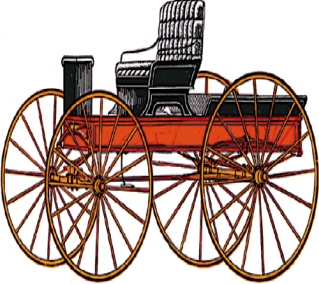

Ohio Carriage Mfg. Company, Columbus, Ohio

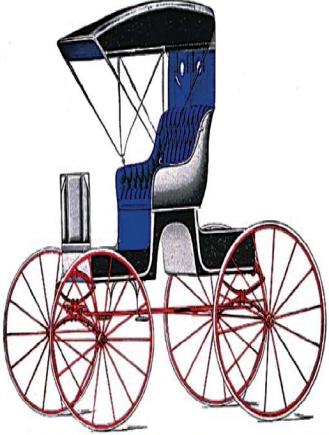

Ohio Carriage Mfg. Co. was a mail-order concern that would ship this attractive runabout direct to your railway depot for $54. The company claimed this vehicle would easily sell for $75 or more at a local carriage dealer.

Velie Carriage Company, Moline, Illinois

By the time their 1915 trade catalog appeared, the days of horse-drawn vehicles were rapidly coming to an end. The Velie line included this No. 604 Driving Wagon, shown here with a classic black body. And it could be furnished in green, maroon, or red.

Ohio Carriage Mfg. Company, Columbus, Ohio

For the 1909 price of $73.75, one could purchase a copy of the Split Hickory Special Short Turn Buggy. Adding Goodyear solid rubber tires raised the price another $15. Heavy, dark blue wool broadcloth was used for the upholstery. Crated for shipment, this buggy weighed about 500 pounds.

Ohio Carriage Mfg. Company, Columbus, Ohio

The Split Hickory Surrey shown here was priced at $87.50...a handsome price in 1909. This one had a black body with a Brewster Green running gear, and dark green wool upholstery. Brewster Green was a popular shade. Some vehicles were finished in austere Quaker Green, best described as greenish black.

Deeds & Hirsig Mfg. Company, Nashville, Tennessee

In the 1890s, Deeds & Hirsig billed themselves as the “Largest Exclusive Vehicle House in the World.” Despite this claim, we’ve found little information on the company. An ancient dealer catalog offers their attractive No. 6 buggy with a cash price of $100 for three buggies, crated and shipped to your depot.

Electric Wheel Company, Quincy, Illinois

Although Electric Wheel Company was one of the preeminent builders of all-steel wagons. The Calkins Farm Wagon from EWC was available at least into the 1920s.

David Bradley & Company, Council Bluffs, Iowa

This famous implement manufacturer operated a large vehicle and wagon warehouse at Council Bluffs, Iowa, for a number of years. An 1890s catalog notes their buying volume allowed them to secure their vehicles from manufacturers at a very low price. The company was buying 1,000 or more buggies per order. The vehicles were then sold under the David Bradley name and guarantee.

Studebaker Bros. Mfg. Company, South Bend, Indiana

Studebaker was one of the largest wagon and vehicle manufacturers. A Studebaker catalog of the early 1900s notes their 65-acre lumber yard usually had over 700 million board feet of lumber, and the factories consumed some 250 million board feet per year.

Northwestern wagons were well known, not only locally, but also in several surrounding states. The demand for wagons was insatiable, finally slowing to a trickle by World War II. Northwestern Mfg. Co., Fort Atkinson, Wis.

In 1906 Moline acquired the Mandt Wagon Co., at Stoughton, Wis., following for decades to come with the Moline-Mandt line. Moline Plow Co., Moline, Ill.

The original Mandt wagons differed slightly from those built later by Moline Plow Co., but had one thing in common with virtually all farm wagons; it was green. Mandt Wagon Co., Stoughton, Wis.

The Troy Dump Wagon shown here was rarely seen on a farm, but was used mainly for building roads and other construction. Often, local farmers were hired when a road job or construction project came to the area. Troy Wagon Works Co., Troy, Ohio.

In 1910, Deere acquired the Moline Wagon Co., at Moline, followed a year later by acquisition of Fort Smith Wagon Co., Ft. Smith, Ark. Shown here is a Deere Ironclad wagon of about 1912. Deere & Co., Moline, Ill.

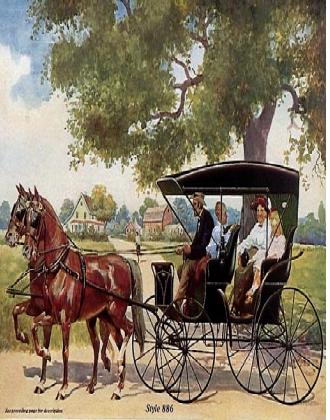

This company was well known for its carriages. Apparently the company made few, if any, wagons. However, a carriage was an essential part of rural life, as shown with this family on a Sunday outing. Velie Carriage Co., Moline,

The John Deere line for 1912 included the Deere Davenport Wagon, apparently a product from its newly acquired Davenport Wagon Co., Davenport, Iowa. Deere & Co., Moline, Ill.

Wagon manufacturers thrived until the coming of rubber-tired wagons and row-crop tractors. As the tractor retired the horse, so also did these new wagons retire the time-honored designs as shown in this attractive model from Miller Wagon Co., Edina, Mo.

Studebaker built farm wagons by the thousands but this only accounted for a small portion of the enterprise. For example, delivery wagons of many styles were mass-produced in the Studebaker factories.

Studebaker Bros. began building wagons and vehicles prior to the Civil War. By 1872, they proclaimed themselves to be the largest vehicle builders in the world.

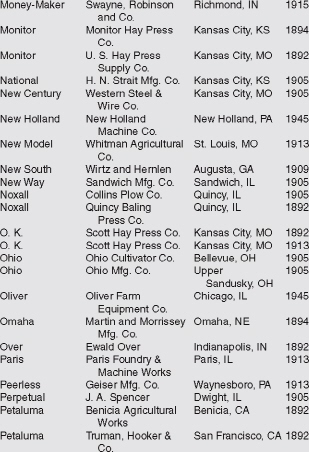

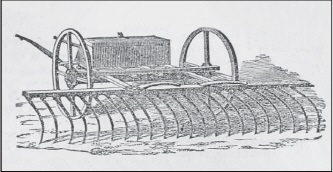

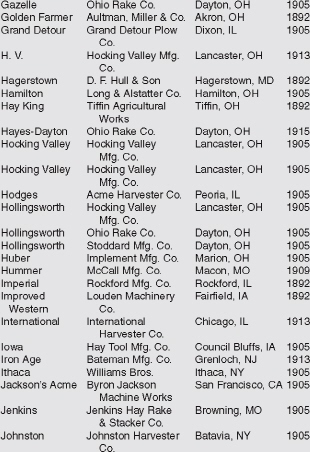

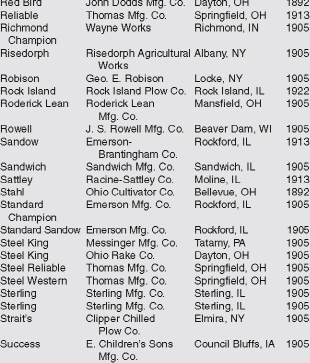

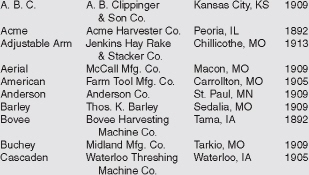

Trade Names

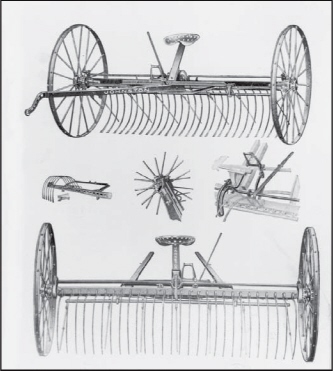

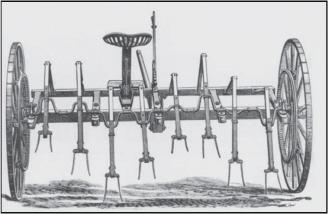

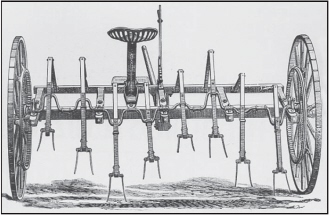

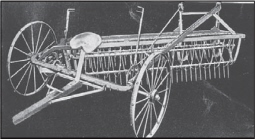

Hay Rakes

The coming of the mower brought with it a demand for a suitable rake. Early examples were the dump rake that gathered the dry hay from the swath and with a hand lever it was deposited into a windrow. Later, a power-lift device was included so that a simple trip lever could be used to raise the teeth.

During the 1880s, the side-delivery rake appeared infrequently, but was fairly well perfected by 1890; within a few years, it became the predominant method, with the dump rake enjoying only a fraction of its former popularity. Another device to make its appearance in the 1880s was the hay tedder, a device for lifting hay so that it would dry, but not leaving it in a windrow. A few companies built combination side-delivery rakes and hay tedders. By that time, however, the benefits of using a tedder were put to question, so the idea gained mediocre support.

Most companies building rakes also built other haying equipment, but a few early companies specialized in this line to the exclusion of all others. As with many other facets of the farm equipment business, companies came and companies fell, many of them leaving business entirely before 1920. Others merged to bolster their position and still others sold out, often at a great loss, to salvage a small return for their efforts.

Acme Harvester Co., Pekin, Ill.

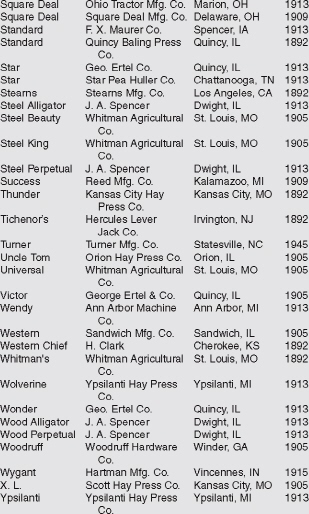

Shown here is an 1899 version of the Hodges “Laddie” Hand Dump Rake. Making straight windrows took constant vigilance as the driver traveled back and forth across the field. Acme Harvester Co., had beginnings going back to 1860.

Albion Manufacturing Co., Albion, Mich.

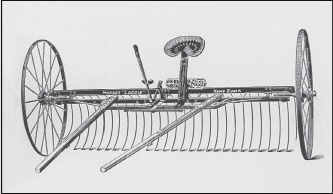

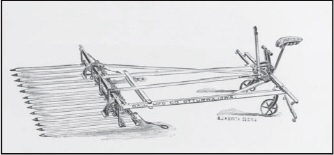

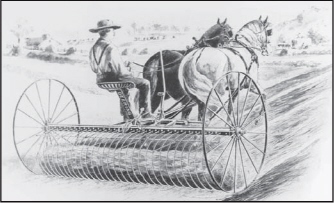

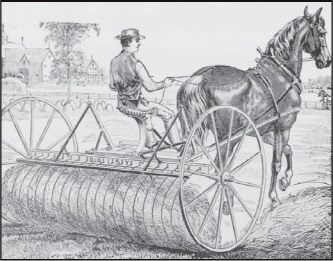

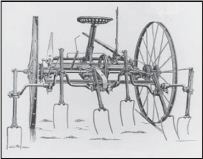

From 1887 comes this engraving of the Daisy Sulky Hay Rake from Albion Manufacturing Co. This one used a foot lever to raise the teeth as the farmer sat astride an iron seat. The Daisy was of wooden construction; even the bar supporting the teeth is a wooden beam, suitably fitted for the rake teeth.

Ames Plow Co., Boston, Mass.

The June 5, 1869, issue of the Boston Cultivator carried a front page article on Burt’s Self-Adjusting Horse Hay Rake. The design was patented in 1867; the following year, 1,500 rakes were built and sold. The editor of the Boston Cultivator commented: “Let those who toiled and sweat over hand-rakes during the last hay-season read the following significant TESTIMONIALS FROM HAYMAKERS.” Then follows about a dozen glowing reports of the new rake.

B.F. Avery & Sons, Louisville, Kty.

After Avery bought the Champion line from IHC, the company gained an already developed line of hay tools. Included was the Champion Hay Tedder. Advertising of the day claimed that hay in heavy swaths would not dry evenly, therefore the tedder was needed to stir the hay so that it would dry evenly. While there was a certain amount of validity in the claim, many farmers considered it not be worth the bother.

A 1916 catalog from B.F. Avery shows its Improved Dump Rake, with the most notable feature being a power-lift system that automatically lifted the tines just by pushing a foot pedal. This eased the work for the farmer considerably. While some farmers of this time still used a dump rake, most had opted for the side-delivery style.

Charles Carlisle, Hartford, Quechee Village, Vt.

From the Jan. 27, 1849, issue of the Boston Cultivator comes this front page illustration of Carlisle’s Patent Improved Horse Rake. Apparently, Carlisle had been having good success with his new design and it was awarded a First Premium by Vermont’s Windsor County Agricultural Society. With this article, Carlisle was offering to sell manufacturing rights to those of other towns or counties who might be interested.

Dain Manufacturing Co., Ottumwa, Iowa

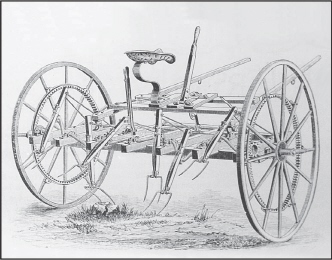

Dain began business in the 1880s at Carrollton, Mo., and eventually moved to Ottumwa. Various kinds of rakes were among the earliest developments, including the Dain Power Lift Hay Rake. This device was marketed for a number of years, with the example shown here coming from a 1900 advertisement.

In addition to various kinds of dump rakes and sweep rakes, Dain also perfected a side delivery rake in the 1900s. This rake became very popular, partly because it was offered by the John Deere Plow Co., through its extensive dealer organization. Eventually, the Dain operation became a part of Deere & Co.

Deere & Co., Moline, Ill.

By 1895, Deere had an extensive line of haying tools: everything from hay tedders, hay forks, hay carriers, hay rakes, hay loaders, hay stackers, mowers, sickle grinders and more. Shown here is the Deere rake of 1895; it was available with either a steel or wood frame.

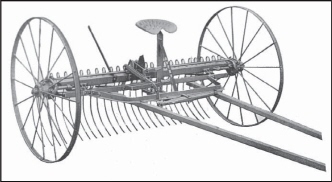

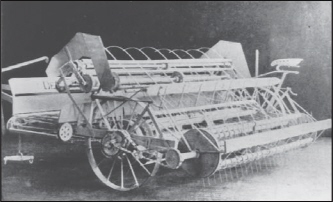

A 1908 John Deere catalog illustrates the company’s New Deere Reversing Side Rake. This unusual design picked up the hay much like a hay loader, then carried it by a conveyor to one side, leaving it in a windrow. Aside from this catalog illustration, little more is found of this very interesting design.

Deering Harvester Co., Chicago, Ill.

Deering, like many other manufacturers, published its catalogs in several languages; this German-language edition of 1899 shows the Deere Automatic Dump Rake. It was offered in 8-1/2, 10-1/2 and 12-foot sizes. The larger sizes required two horses.

J. Dodds, Dayton, Ohio

The Hollingsworth rake was introduced by Dodds about 1875 and remained on the market for a few years. It featured an all-steel design and this was out of the ordinary for most farm equipment of the time. Outside of this illustration, virtually nothing is known of the company.

Emerson-Brantingham Co., Rockford, Ill.

In 1907, Emerson Manufacturing Co. offered its Alfalfa Champion Rake. At the time, alfalfa or lupine as it was sometimes called—it still is in Australia and some other parts of the world, was gaining greatly in popularity as a forage crop. Since alfalfa was a heavy crop, Emerson devised its own alfalfa rake with a heavier design than ordinary.

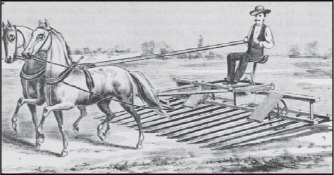

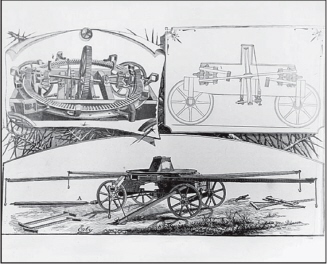

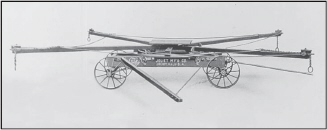

Sweep rakes were a popular implement in some areas. With this 1919 design, the horses pushed the rake ahead of themselves. Once the rake was loaded a lifting device raised the teeth off the ground and the load was taken to a convenient place for stacking.

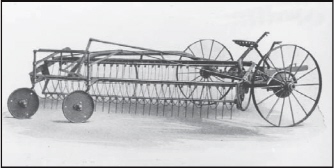

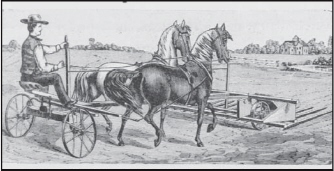

Emerson-Brantingham developed its No. 166 Side-Delivery Rake sometime prior to this 1919 model. While many side rakes used a single tail wheel, this model featured two tail wheels for better stability on rough ground. With this design, one wheel could support the tail of the rake, thus keeping the rake teeth from digging into the ground.

Gale Manufacturing Co., Albion, Mich.

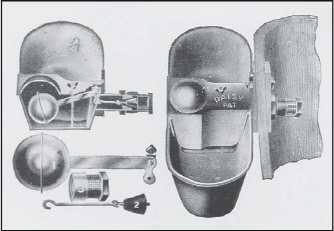

An 1889 advertisement illustrates Gale’s Daisy Hay Rake. It appears to be a successor to the Daisy from Albion Manufacturing Co. see previous. Little history is known of Gale, but it seems to be a safe assumption that Albion was indeed a forerunner of the Gale line.

Gilliland, Jackson & Co., Monroe City, Mo.

Patented March 9, 1886, the Daisy Ricker and Rake are shown here. The ricker is pictured to the left as it transfers a load of hay to the stack. On the right is the rake, free from its burden and ready to return to the field for another load. These devices were very popular in certain areas where outdoor haystacks were built instead of storing the hay in a barn.

While the Daisy rake was a push rake, the Missouri Hay Rake of 1889 was pulled with the team forward. Apparently, the company was experiencing great success at the time, but future years leave no mark as to its activities. Possibly, the line was sold out to another manufacturer, but trade directories of the early 1900s show no listings for the Daisy or Missouri lines.

Grand Rapids Manufacturing & Implement Co., Grand Rapids, Mich.

An interesting study of gears and linkages is provided with the Grand Rapids Hay Tedder of 1895. By using a combination of tongue and shafts, this tedder could be used with one horse or two. The advertisement noted that the company had a few hundred machines on hand for immediate shipment. Beyond this notice, little else is known of the company.

Hay Tool Manufacturing Co., Council Bluffs, Iowa

From 1905 comes this advertisement of push rakes and sulky rakes in various styles. Apparently, the company had a sizable trade, since it engaged jobbing houses at St. Louis and Kansas City. However, the advertisement also notes that N.H. McCall was manager of the firm. It would appear that his subsequent activities were with McCall Manufacturing Co., which follows.

International Harvester Co., Chicago, Ill.

For 1920, IHC offered its combined side rake and tedder as part of an extensive line of haying tools. Of the original partners that formed IHC, Deering and McCormick both had well-developed hay tool lines and these were expanded in the following years. Eventually, the idea of a combined rake and tedder disappeared.

Into the 1920s, IHC continued to offer its International hay ted-der; it was virtually identical to the McCormick hay tedder introduced some 30 years before. Some farmers saw the tedder as an essential part of their farm equipment, while others saw it as something nice to have. Others saw no use for it at all.

Johnston Harvester Co., Batavia, Ill.

With an implement such as the dump rake, there were few basic differences from one make to another. However, each manufacturer had a slightly different approach to the lifting system, wheel design or perhaps the curvature of the teeth. Shown here is the Johnston design, ca. 1910.

Did You Know?

Old cultivators are a desirable collectible, although the market values still are very low. Nicely restored ones can command $100 to $200 or more.

Johnston’s Steel Hay Tedder, ca. 1910, was a rather heavy machine; a noticeable difference was the use of three-tine forks (most contemporaries used a two-tine fork). The entire design of the machine was such that it was almost impossible to wear out, especially if oil was kept on the moving parts. Most farmers used too much oil rather than too little, so these machines could run for years with very little attention.

Keystone Manufacturing Co., Sterling, Ill.

During the 1880s, Keystone developed its hay tool line, including this Sterling Hay Tedder. This eight-fork machine was of wood construction. An interesting drive mechanism was used; the crankshaft for the forks is driven from large internal gears mounted on each wheel of the tedder. With its tedder, rake, mower and hay loader, Keystone claimed to have “The four best haying tools in America.”

By 1894, Keystone had developed a side-delivery rake. This model was built entirely of wood; even the rake bars were of wood. An accompanying article explains to farmers that it was essential to rake the hay at the proper time and by delaying, “it will surely be sunburned on top while yet green and damp underneath.” Keystone became a part of International Harvester in 1904.

McCall Manufacturing Co., Macon, Mo.

A 1903 advertisement lists McCall Manufacturing Co., at Moberly, Mo. Then the Hay Tool Manufacturing Co. (see previous listing) appears with McCall as the General Manager. A 1908 advertisement shows McCall Manufacturing Co., at Macon, Mo. However, the McCall line attracted considerable attention since it was handled by most of the major machinery distributors in the Midwestern states.

McCormick Harvesting Machine Co., Chicago, Ill.

About 1900, McCormick advertised its All-Steel Hay Rakes as “Kings of the Meadow.” Indeed, this unit was available in three different sizes; the 8-foot with 20 or 26 teeth, the 10-foot with 26 or 32 teeth and the big 12-foot rake with 32 or 40 teeth. International Harvester Co., continued building virtually the same rake for years to come.

New Idea Spreader Co., Coldwater, Ohio

With its purchase of Sandwich Manufacturing Co., about 1930, New Idea gained a well-developed line of hay tools, including the Sandwich side-delivery rake. Building on this experience, New Idea offered hay rakes of various kinds, including this one of the late 1930s. The company continued with various side-delivery rakes for many years after.

D.M. Osborne & Co., Auburn, N.Y.

By the 1890s, the Osborne All-Steel Self-Dump Rake had taken the form shown here. An important feature was Osborne’s early adoption of the self-lift design; this used power from the wheels to raise the tines, rather than requiring the farmer to raise and lower the rank with a hand lever with great frequency. This style was made in 8-, 10- and 12-foot sizes.

Like most companies of the time, Osborne considered the tedder to be an essential part of the hay tool arsenal. Its design shown here was somewhat different than its contemporaries. Each fork was equipped with a spring mechanism in case the forks hit an obstruction, preventing or minimizing breakage. The drive system for the tedder was at the center of the frame, rather than on the wheels; this kept hay from getting tangled in the gears and mechanism.

Plano Manufacturing Co., Plano, Ill.

Plano Manufacturing Co. had developed an excellent line of hay tools by 1900, including this combination hand-lift and self-lift rake. With this one major feature to its credit, the Plano looked much like its contemporaries. In 1902, Plano became a part of International Harvester Co. This illustration is from a German-language edition of the 1900 Plano catalog.

Rude Bros., Manufacturing Co., Liberty, Ind.

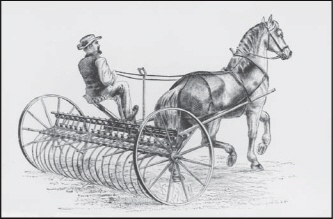

The Mascot Sulky Hay Rake was offered by Rude Bros., in 1887. At that time, the company was offering a wide range of “Indiana” implements, including wheat drills, corn drills and many other items. The dump rake shown here is of an all-wood design. Eventually, Rude Bros. began manufacturing manure spreaders. They were so successful that the company eventually built manure spreaders exclusively.

Sandwich Manufacturing Co., Sandwich, Ill.

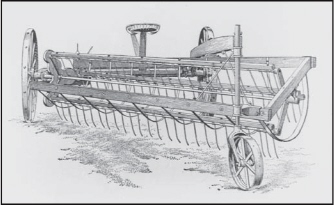

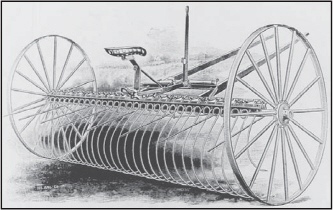

Particularly in the Midwestern states, the Sandwich side-delivery rake was one of the most popular of its time. This model of 1903 underwent little change for several years; some of these early models were still in the field 40 years later. Eventually, tractor rakes designed for higher field speeds brought an end to their many years of service. The Sandwich line was the basis for the New Idea hay tool line; the latter bought out Sandwich about 1930.

Stoddard Manufacturing Co., Dayton, Ohio

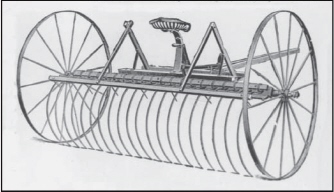

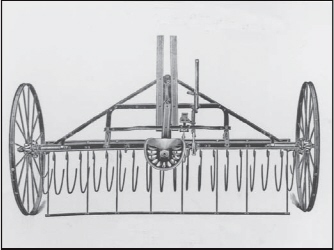

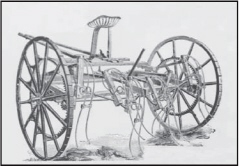

Perhaps the old adage that “history repeats itself” might be appropriate for the Beck side-delivery rake of the 1880s and 1890s. Over the years, various companies built “wheel rakes” somewhat in the form of the Beck; eventually the design was perfected. Today, the wheel rake is an important design. Unfortunately, it sold very poorly when it was first offered in 1887.

Thomas Manufacturing Co., Springfield, Ohio

Part of the 1887 Thomas hay tool line was its Royal Hay Rake, a hand-lift dump rake of all-wood construction. The simple lift mechanism with its linkages is quite evident in the engraving; one can only be amazed at the stamina required to work the lever up and down, almost constantly while raking a field of hay into windrows.

As noted, leading agriculturists of the day considered the hay tedder to be an essential part of the hay tool arsenal. The thinking was that leaving the hay in the swath to dry completely would sunburn the top while leaving the rest damp and uncured. Eventually, farmers quit buying into the argument, so the hay tedder fell into disuse. Shown here is the Thomas machine of 1887.

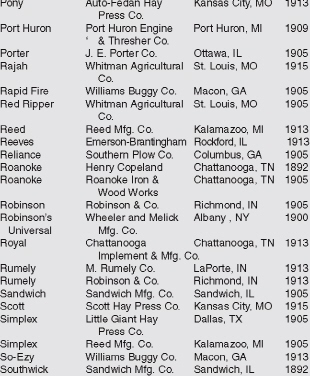

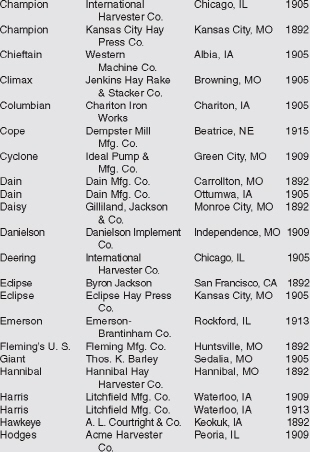

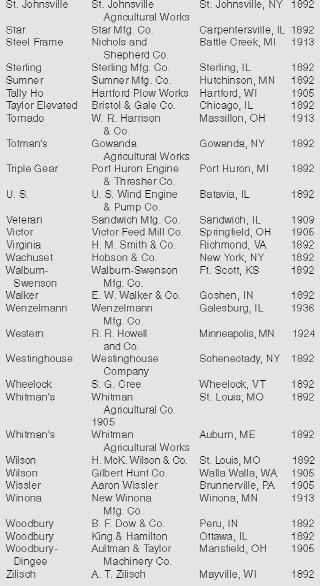

Trade Names

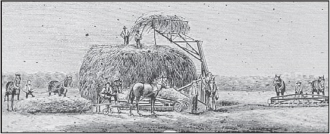

Hay Stackers

In certain areas, the hay stacker developed as an important part of the hay harvest. Usually these areas stored hay in outdoor stacks rather than in barns. The hay stacker mechanized the process to some extent. A few of these stackers are also illustrated in the Hay Rakes section, especially because a few were intended as combination machines to rake and stack the hay crop.

Dain Manufacturing Co., Ottumwa, Iowa

Joseph Dain began building hay equipment in Kansas City in 1882. The company moved to Carrollton, Mo., in 1889, remaining there until removing to Ottumwa in 1900. Eventually, the Dain plant came under ownership of Deere & Co. Shown here is the Dain Automatic Steel-Armed Hay Stacker of 1892; the stacker offered at Ottumwa in 1900 was virtually identical.

Famous Manufacturing Co., Chicago, Ill.

In 1884, Famous Manufacturing Co., illustrated its Peerless Combined Hay Stacker & Derrick, noting that it was the only such machine in existence. It was also claimed that the Peerless was the only machine to lift to the height of the stack, then allowing the hay to slide off the arms. Little else is known of this particular device.

Wyatt Manufacturing Co., Salina, Kan.

From the 1930s comes this wood-frame stacker from Wyatt. Its Jayhawk line of stackers gained wide renown; there were Jayhawkers present almost everywhere stackers were used. The company modernized its machines in the 1940s and continued building them for some time after. Eventually, the hay baler took precedence and, when “big bales” came along, demand for the Jayhawk dwindled.

Trade Names

Hay Tools

Under this heading one could include a small book in itself, given the multitude of hay carriers, pulleys, hay forks, slings, pitch forks and other items incidental to the harvesting and handling of hay. Some of these items are already displayed in various guides to antiques and some will be found scattered in various sections of this book. Given the huge amount of material encompassed by this title, this section gives but a cameo view of the larger scene; for instance, in 1910, there were more than 50 different kinds of hay carriers offered to the farmer.

Some of the items shown here have come to the ranking of a collectible farm antique; very early wooden forks for instance, might bring $100 or perhaps even more, while common metal forks usually sell from $10 and upwards. An ordinary hay carrier might now bring $40 and various kinds of hay knives might sell from $15 to $35.

Readers should consult various pricing guides, since many hay tools are usually listed. Eventually, the author hopes to compile a guide to farmstead tools and equipment as a comprehensive treatment of the subject. Attempting this within the present volume would be to deny illustration of many other important pieces of farm equipment.

Fleming & Sons Manufacturing Co., Huntsville, Mo.

Numerous kinds of hay stackers, buck rakes, push rakes and related equipment emerged in the 1880s. These designs were well developed during the 1890s, with this offering from Fleming coming in 1899. Additional illustrations of this equipment can be found under Hay Stackers and other hay equipment sections within this book.

Hoth Hay Mower Co., Luana, Iowa

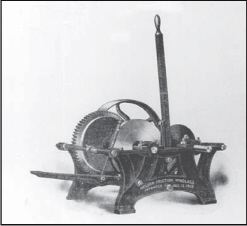

The origins of this company are unknown; in the 1930s, Hoth offered this belt-driven hoist specifically for raising hay into a barn. Through a rope system, the hoist could be operated directly from the load. Machines like this eliminated the need for a horse to pull hay into the barn; many “farm kids” got the chance to walk an old plow horse for this job. With hay-making in full swing, there were a lot of trips back and forth in a day’s time.

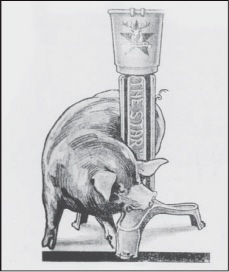

Hunt, Helm & Ferris Co., Harvard, Ill.

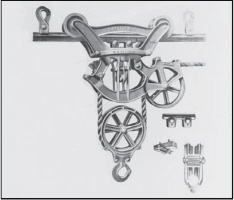

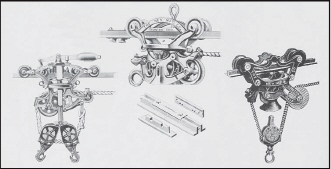

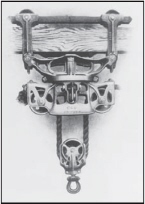

In 1904, this company offered two new hay carriers to the farmer, supplementing its already extensive line of Star hay tools. This one is shown with the track latch plainly visible to the left. As the carrier returned to the left, it engaged the latch, holding it firmly in position. A mechanism within the carrier tripped it from the latch after locking the load into the carrier for the lateral journey into the depths of the barn.

Louden Machinery Co., Fairfield, Iowa

By 1888, Louden had developed the hay sling for carrying hay into a barn. Usually two or three slings were placed in the load, one at the bottom, with one or two more being laid out as the load was built. At the barn, the farmer hooked the two ends of the sling into the pulleys as shown, thus carrying the loose hay into the barn. At the proper time, he pulled the trip rope, releasing one end of the sling and completing the process.

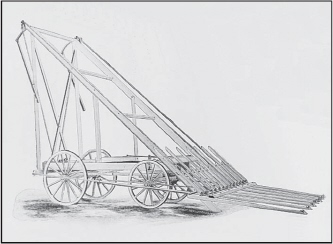

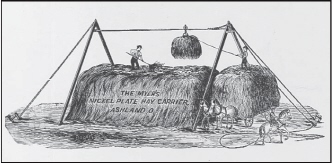

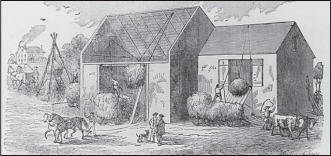

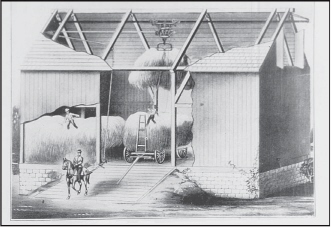

For outside stacking, Louden offered this design in 1888. With a unique arrangement of ropes and pulleys, a hay sling carries another load to the top of the stack. While this artist’s conception of a hay stack goes to the extreme, building a straight and square hay stack was indeed an art, mastered by some and giving mediocre results for many others.

From about 1910 comes this illustration of a Louden Senior Fork Carrier. The continued building of large barns at the time demanded larger and heavier hay carriers, with this one featuring roller bearings and a swivel frame. Many hay carriers were operated for decades with little or no attention.

Mechanizing the hay harvest was important to the Louden operation; this illustration from about 1915 demonstrates the Louden Power Hoist, showing its operation. With an operator at the hoist, lifting the load was under complete control, as was the return of the carrier for the next load. The hoist is being operated by a Monitor engine from Baker Manufacturing Co., Evansville, Wis.

F.E. Myers & Bro., Ashland, Ohio

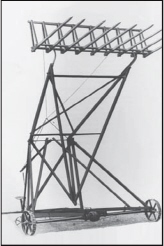

A pioneer in the development of hay tools, Myers offered this portable hay stacker in 1888. It was essentially a framework carrying the same kind of track as would have been used for unloading into a barn. The man with the trip rope could drop the load at any point; far to the back is another man ready to stack the coming load.

Did You Know?

The Red Chief table-top corn sheller was priced at $2.25 in 1918.

From 1890 comes this catalog illustration demonstrating the Myers system to prospective buyers. Many early barns had a drive-through area, since in earlier times the hay was pitched by hand into the barn for mowing. With this center-mounted carrier, hay could be carried to either end of the barn using a suitable and rather complicated pulley arrangement.

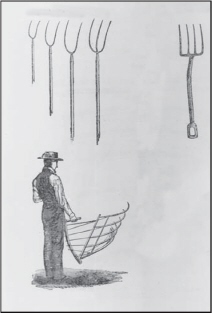

While some of the hay fork designs pictured here were unique to the Myers line, some were commonly used by almost every manufacturer. This illustration from an 1890 pictures the most commonly used styles of the time. Not shown is the hay sling, previously referred to in this section.

By 1890, Myers had developed its New Myers’ Nickel Plate Hay Carrier for outside hay stacks. Its cable-track design was a new feature. Ordinarily, this unit was shipped without the support timbers; they could be secured locally, with the hardware fitted on-site. This design was fairly popular, especially when the hay crop was larger than the capacity of the barn.

Today’s collectors of farm antiques often encounter pulleys of various kinds. Indeed, there were a host of different styles. In most instances, a wooden pulley was preferred to one of iron, since it was considered that wood and rope got along better than rope and iron. While this selection of pulleys is from an 1890 Myers catalog, there were countless others from dozens of different companies.

In 1909, Myers introduced its new Automatic Grapple Fork. This design was suitable for handling loose or baled hay. It was also easy to set and could handle long or short hay with ease. In contrast, the single- and double-harpoon designs were best suited to long material such as timothy. Within a few years, the grapple fork was adopted by most farmers; the hay sling, the harpoon fork and other designs now sat quietly in a corner.

Ney Manufacturing Co., Canton, Ohio

A close competitor to the Myers line was the Ney; this company was well known for its hay tools. The size of its operation was such that it maintained branch houses at Minneapolis, Peoria, Ill., and Council Bluffs, Iowa. Ney hay tools were marketed for many years, with this 1904 illustration showing three of its hay carrier designs.

North River Agricultural Works, New York, N.Y.

An 1866 catalog of North River Agricultural Works illustrates Beardsley’s Patent Hay Elevator or Horse Power Fork. It consisted of a so-called horse pitchfork, also shown in this heading, along with a suitable arrangement of ropes and pulleys. Despite the dearth of advanced features, this system still represented a major improvement over hand methods.

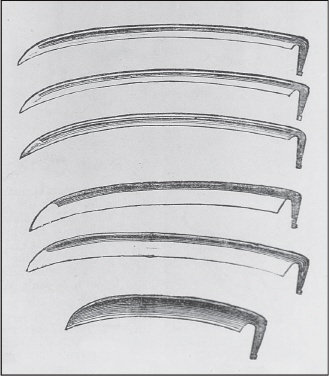

While the mowing machine was gaining favor by 1866, the scythe was still an important part of the farm tool arsenal. Shown here are various styles of the period, including from top to bottom, grass, lawn, grain and three styles of bramble or bush scythes. With the scythe, the farmer needed a grindstone for regrinding, plus a whetstone carried in the pocket, to maintain a razor-sharp edge.

In its 1866 catalog, North River Agricultural Works offered numerous kinds of forks; four styles of hay forks or pitch forks are pictured to the left, and at the bottom is Grant’s Patent Grain Cradle. Using one of these required a bit of dexterity and practice. To the right is a four-tine manure fork. In addition, North River offered other kinds of forks for special purposes.

Clement’s Improved Horse Hay Fork is shown at the top of this 1866 illustration; below it is Clowe’s Patent Straw and Barley Fork, another of the special designs developed for a special need. This one could be furnished with wood or steel tines, as desired. At the bottom of this illustration is Palmer’s Excelsior Self-Sustaining Horse Pitchfork, another early design; the company claimed to have made 7,000 of these forks in 1863, with another 12,000 in 1864.

J.E. Porter Co., Ottawa, Ill.

An early manufacturer of hay tools and equipment, Porter offered this hay-carrier design in 1905. Porter, among others, initially used a wooden track for the carrier instead of the steel design shown here. Large barns usually had the track and its mountings installed when the structure was built; doing so afterwards was a formidable project unless, of course, the barn was filled with hay.

Already in 1907, Porter offered its Nelson Friction Windlass that was patented a couple of years earlier. This engine-driven hoist mechanized the operation of getting hay into the barn and gained a certain popularity. Porter continued manufacturing hay tools into the 1930s, but a 1939 listing shows that repair parts for the Porter line were available from Louden Machinery Co., listed previously in this section.

Whitman & Barnes Manufacturing Co., Chicago, Ill.

Whitman & Barnes was famous for its Diamond line of hay tools. This illustration of the early 1900s shows a Diamond carrier installed in an early barn. The company gave instructions for mounting the track: “Scaffold by placing a rope from rafter to rafter, say six feet from the ridge pole or peak and about 10 feet apart. Then place an extension ladder across the ropes with a board to stand on. Now nail one rafter bracket at each end of the barn, draw a line from one end to the other and stretch it tight.” Once this was completed, the same process continued, mounting each bracket to the line for perfect alignment of the finished track.

Did You Know?

Today, most farm wagons in reasonably good condition will bring $500 or more, while a good carriage will be much more expensive. Nicely restored carriages— especially one that is quite fancy and equipped with brass driving lights and other paraphernalia— can often bring $2,000 or more.

For 1908, Whitman & Barnes offered this heavy hay carrier utilizing a total of eight truck wheels to carry the load. Since wooden pulleys were preferred by some, the idler pulley at the bottom side of this carrier is made of wood, probably containing a hardened steel bearing at its center.

Some farmers and some manufacturers, for that matter, preferred a 4-by-4 inch wooden track to a steel track. One such design was offered by Whitman & Barnes in the early 1900s; this particular design was patented in 1907. Eventually, the wood-track design fell into disfavor with the steel track being found preferable.

The hay sling was a popular method of lifting hay into a barn. Shown here is the Whitman & Barnes design of the early 1900s. One of these was placed on the floor of the hay rack, followed by one or two more as the layers of hay accumulated. After going into the barn, the load was dropped by pulling the trip rope shown at the center of the illustration. This released a latch, separating the two halves of the sling.

As noted earlier in this section, every supplier of hay tools offered a wide range of pulleys and sheaves to route the rope. The vast majority of these pulleys were of hard wood, carried by a steel or iron shackle. Some were bushed with steel and some with rawhide. Some had plain bearings and others had roller bearings. The different examples were almost without limits.

Grapple forks came into popularity during the early 1900s, eventually displacing the hay sling, the harpoon fork and other devices. Whitman & Barnes, like other companies, offered many styles and sizes of grapple forks. Some were of four-tine design and others used six tines. The Jackson fork and the California fork, both shown at the bottom of this illustration, eventually fell into disuse. After 1915, Whitman & Barnes disappeared from the scene.

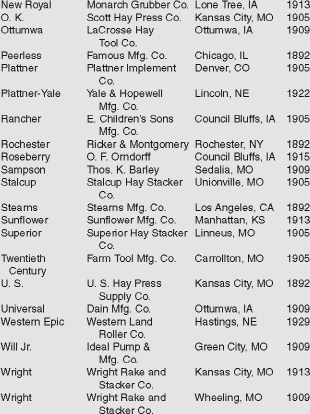

Trade Names

Hemp Mills

Hemp mills gained limited attention, particularly during the 1800s; after suitable treatment, the fibers were used for cordage. Of the farm equipment manufacturers, International Harvester and some of its predecessors were among the leaders, along with a few others. Interest in hemp waned until World War I. At that time, the scarcity of imported materials led to a renewal of domestic hemp production; this phenomenon repeated itself during World War II. Further information on hemp machines can be found in the author’s 150 Years of International Harvester (Crestline/ Motorbooks, 1981).

An 1892 advertisement from C. Aultman & Co., Canton, Ohio. For a time, this company built the Shely Hemp and Fibre Brake. Chances are that production of this machine was very limited, given the general lack of interest in this crop. A few other companies built this equipment and most of them have disappeared without a trace of their activities.

Hog Equipment

If there were room in this book, one could include literally dozens of hog oilers, hog waterers and related items, most made of cast iron. In recent years, hog oilers or hog greasers have become an important farm collectible, with some of these bringing considerable sums. This market seems to be quite volatile. While a farmer might sell an old abandoned oiler for $5 or $10, a collector might give $100 or even much more for a particularly desirable style. Since the collecting of hog oilers and hog waterers is a relatively new hobby, many of the current price guides to farm collectibles do not include any pricing for these items. Buyers and sellers alike are advised to familiarize themselves with these items at various shows, flea markets and the like to gain an idea of the values in their area.

B-B Manufacturing Co., Davenport, Iowa

By the early 1900s, numerous companies were offering hog wa-terers similar to this one; it was mounted to a large barrel or a livestock tank for automatic watering.

Bain Bros., Manufacturing Co., Cedar Rapids, Iowa

Bain Bros. offered its Helm Sanitary Hog Fountain in 1923. This was a valveless and floatless design, totally automatic and used mainly for hog and sheep watering.

From a 1923 catalog comes this illustration of Bain’s Faultless Hog Waterer, available in 55-gallon and 90-gallon sizes. This one also had a door in the side so that during cold weather a kerosene lamp could be placed beneath to prevent freezing. Refilling the lamps was a job that came along every couple of days. Most of the time, it seemed that the weather was at its worst during this task, whether it was rain, wind, snow or sub-zero temperatures.

Challenge Co., Batavia, Ill.

With its large trade following, Challenge had no problem in selling its Daisy Hog Waterers. Thousands of these appeared all over the country and a fair number still appear today. As shown here, the Daisy was attached to the side of a barrel, giving the farmer a cheap and easy method of obtaining a self-waterer. This one had a 1910 price of $3.

Did You Know?

Antique corn shellers are a popular farm collectible; small one- and two-hole designs usually bring $50 or more, while larger four- and six-hole versions fall in the $250 to $500 range.

Hartman Co., Chicago, Ill.

Among its many products, the Hartman Co., catalog of 1920 offered the Majestic Valveless Hog Oiler, citing its benefits in improving the health of the animals, adding to their comfort and manifesting improved weight gains.

J.D. Martin & Co., Oskaloosa, Iowa

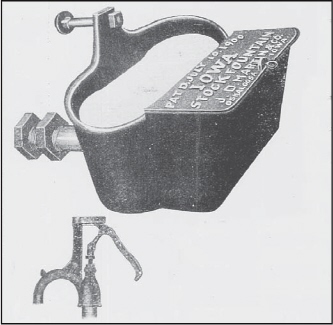

The Iowa Automatic Stock Fountain first appeared about 1900; this one did not use a float, but worked off of a spring mechanism. Also pictured in this 1909 illustration is a frost hydrant to provide water wherever wanted and at any time of year. In the early 1900s, farmers got their first taste of running water on the farm by digging in water pipes to the barn and other areas.

Maytag Co., Newton, Iowa

Hawkeye Automatic Hog Waterers were a 1910 product of Maytag Co. As shown here, the waterer was connected directly to a large barrel, but could also be fitted to a stock tank or even to a pressurized water pipe. Sometimes the whole affair was bolted to a wooden skid, making the outfit semi-portable.

National Oiler Co., Richmond, Ind.

A 1914 advertisement illustrates the National Hog Oiler. The promotional material that accompanied this unit gave some very persuasive claims as to the benefits of these oilers. With hog oilers and related equipment, the relatively new livestock care industry gained new impetus.

O.H.C. Manufacturing Co., Peoria, Ill.

Hog oilers took on virtually every shape and size imaginable. This interesting cast-iron design is from 1914. Each company tried to offer what it thought was the simplest, cheapest and best hog oiler on the market. Most designs lasted but a few years, to be replaced with still other designs

O’Neil Implement Co., Marseilles, Ill.

As part of its 1910 line, O’Neil offered this combination hog trough and twin oiler in one unit. A large unit is placed at one end, with a small unit at the other. Between them is a heavy cast-iron trough. This outfit sold for $15.

Rowe Manufacturing Co., Galesburg, Ill.

In 1914, Rowe offered its Row Rubbing Post, a design patented by Alvin V. Rowe. Presumably, the company also manufactured other items, but, as with many small companies, little or no history can be found.

Illinois Implement Co., Peoria, Ill.

No information regarding this firm has been located outside of this 1914 advertisement. Featured was the Star hog oiler, another design competing with dozens of others for a share of the hog equipment market.

Starbuc Manufacturing Co., Peoria, Ill.

For reasons now obscured by time, Star hog oilers were advertised simultaneously by Illinois Implement Co. shown above and Starbuc Manufacturing Co., also of Peoria. The advertising is identical, even using the same engraving. Curiously, the same advertisements occur in the same issue of Farm Machinery Magazine.

Sterling Foundry Co., Sterling, Ill.

For manufacturers up to the 1930s, iron castings were the preferred method of making an article. Small foundries were a frequent sight; many small towns were within 20 miles or less of a foundry. Thus hog waterers and similar items could be readily manufactured. The “Best” hog waterer from Sterling Foundry Co., was a 1915 creation.

Weldex Manufacturing Co., Richmond, Ind.

This 1914 design was called the Weldex Wonder Oiler; it was unique in its design, using welded steel components almost exclusively. A few manufacturers began using welded steel fabrication at this time, but progress was slow and many pieces of farm equipment into the 1930s still employed iron castings to a great extent.

Horse Powers

By the 1830s, the tread power shown in this section had become a practical machine. As shown in various illustrations in this section and scattered throughout this book, are various kinds of tread powers. The tread power consisted of a moving belt, usually constructed of heavy wooden slats connected at each end by an endless chain. While most of these were for horses, smaller ones were also made as dog powers or sheep powers. The tread power was also called a railway power; the two terms are synonymous.

Horse powers and sweep powers are the same thing; farmers sometimes simply called them “powers.” These machines were of several varieties. First, the power was either a low- or high-speed power. The earliest designs were by the Pitts brothers, built by them subsequent to their development of the threshing machine in the 1830s. It is generally considered that the Pitts was the first successful sweep power. It was later modified and improved as the Pitts-Carey power.

Another important design was the Woodbury power; this one appeared in the early 1850s, but mechanical problems did not bring it to the forefront. Eventually, W.W. Dingee of J.I. Case Threshing Machine Co., modified the Woodbury power; from it came the best known of the later styles, the Dingee power. This model was built and sold in large numbers by J.I. Case.

Numerous other styles appeared and many were built under license from its respective patentees. Especially before 1910, many threshing machine companies also offered a sweep power. In most cases, the thresher manufacturer built the power, using the design perfected by others. Evidence of a changing source of power, is the fact, that in 1915 there were still more than 30 different companies making sweep powers, plus at least a dozen offering railway powers. By the 1930s, there were only a half-dozen companies offering powers. After World War II, the era ended altogether.

Small two- and four-horse powers are found occasionally and even one that is well rusted can bring $50 or more. The large powers are rarely found, so there is no established market. Tread power or railway powers are very scarce. Again, there seems to be no established market. Small dog powers for butter churns and the like can bring $500 or more.

Appleton Manufacturing Co., Batavia, Ill.

In 1917, this one-horse tread power sold for $90. This style was called a “down” power because it had no wheel mounting for portability. With most farm equipment of the time, a “down” machine was for floor mounting, while a “mounted” or “portable” style was equipped with wheels. Depending on the walk of the horses, 32 to 36 rpm on the reel shaft, main shaft gave 96 to 108 rpm on the band wheel.

This four-horse down-power was dubbed the Modern Hero by Appleton in its 1917 catalogs. This power was geared to give 56 revolutions of the jack shaft for every round of the horses. By 1920, Appleton no longer manufactured powers, according to industry listings.

Aultman & Taylor Machinery Co., Manfield, Ohio

An 1890 catalog from Aultman & Taylor illustrates its sweep power as used with the Aultman & Taylor grain threshers. The sweep power was a viable alternative to the steam engine, especially when there were plenty of horses available. Eventually, though, the steam engine took precedence; it required no rest stops and far less work than handling eight, 10 or 12 horses.

Buffalo-Pitts Co., Buffalo, N.Y.

The Pitts brothers began building threshers in the 1830s and developed the Pitts Power soon after. It was later modified as the Pitts-Carey power and remained on the market at least into the early 1900s. This example of 1895 shows the Pitts two-speed mounted power. Above it is shown ready for work; below it is ready to move to another job.

Challenge Co., Batavia, Ill.

Small horse powers were offered by Challenge into the 1920s. Shown here is a small unit made for two or four horses. Small powers like this one were often used for sawing wood, grinding feed and other light jobs around the farm.

A.B. Farquhar Co. Ltd., York, Pa.

Into the 1890s, Farquhar came with its Climax Horse Power, suggesting it for threshing and other farm duties. This was a down-power and the engraving illustrates the rather complicated system of gearing required for these machines. The sweep arms were fitted into the square sockets noted at the top of the main drive casting.

Farquhar Railway Horse Powers were warranted to equal any tread power in use; this engraving of the early 1900s shows the small carrier wheels built into the track or tread of the machine. Also evident is the brake lever on the band wheel for stopping the machine.

Harrison Machine Works, Belleville, Ill.

For 1903, Harrison offered the Dingee-Woodbury power, essentially the same machine as that developed and built by J.I. Case Threshing Machine Co. The Dingee design emerged as probably the best of the sweep powers, although the steam-traction engine and eventually the tractor, took away the need for sweep powers.

Did You Know?

Bone cutters can now fetch $100 or more.

Heebner & Sons, Lansdale, Pa.

A 1910 listing shows Heebner’s Double-Geared Level-Tread Power. This one-horse power was designed for small threshers, corn shellers and similar equipment. Heebner also built small threshers and various other farm equipment.

Joliet Manufacturing Co., Joliet, Ill.

Ostensibly built to operate its own corn shellers, as well as other equipment, the Joliet Pitts Power was built on the Pitts design, as compared to the Dingee design, previously noted in this section. This illustration goes back to about 1908. While Joliet continued making corn shellers for decades to come, little else is known of its Joliet-Pitts Power.

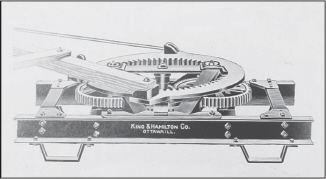

King & Hamilton Co., Ottawa, Ill.

This company manufactured many items of farm equipment, with this two-horse power being a later design, probably of the late 1920s. The all-steel frame lowered the power and lightened the weight; in addition, the power didn’t rot away in a few years of being exposed to the weather. By 1940, less than half a dozen companies were making sweep powers.

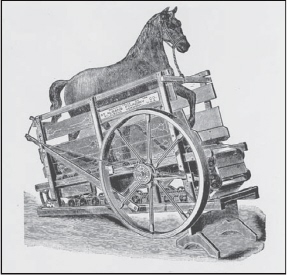

Kingsland & Ferguson Manufacturing Co., St. Louis, Mo.

An 1884 advertisement from Kingsland & Ferguson illustrates its Carey Horse Power, staked and ready for operation. Mounted powers became very popular upon their release. A large down-power for eight or 12 horses would weigh at least half a ton. Since there was no means of lifting anything outside of the power provided by men and horses, a portable machine of any kind was always welcomed.

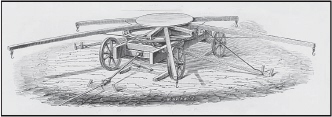

Roberts, Throp & Co., Three Rivers, Mich.

For 1882, this company offered the Improved Pitts Power, also known as the Carey Power. This heavy machine was mounted and featured a two-speed output, as is shown in the engraving. The speed jack is built into the system, utilizing a heavy casting that could be move-into or out of gear, as desired. With this power, the thresherman had the choice of 76, 79 or 103 revolutions of the output shaft to every round of the horses.

St. Albans Foundry Co., St. Albans, Vt.

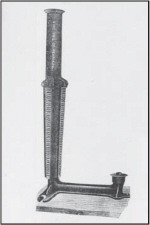

From 1881 comes this illustration of the St. Albans one-horse power, a small unit for various farm jobs. The company suggested that this device could mechanize butter churning, grinding, sawing wood, cutting fodder and other uses. St. Albans manufactured a wide range of farm implements.

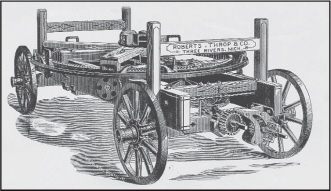

Sandwich Manufacturing Co., Sandwich, Ill.

Sandwich Manufacturing Co. was instrumental in the development of the spring-type corn sheller; this design gained great popularity in the 1880s. For a power source, Sandwich offered its Young Samson Eight-Horse Mounted Power. This design was intended to operate the largest Sandwich shellers and could also be used with threshers and other farm machines. After New Idea took over about 1930, the latter continued to offer small powers suitable for operating grain elevators into the late 1930s or perhaps slightly longer.

Trade Names

Household Equipment

This heading has been and continues to be the subject of numerous titles, antique price guides and nostalgia. The primary purpose of this section is to acknowledge, rather than ignore the role of the farm household in the overall picture. Even though the farmer of those bygone days spent many hard hours in the hot sun or the freezing cold, the housewife also did her share under the same conditions. Beyond the usual household duties, it usually fell to the housewife to look after the poultry, skim the cream, churn the butter, can the garden produce and other jobs too endless to name.

Various parts of the household activities will be found under headings such as Garden Equipment or Washing Machines. Some items presented here are found nowhere else in this book. For a value guide, the reader should consult any of many guides on the subject.

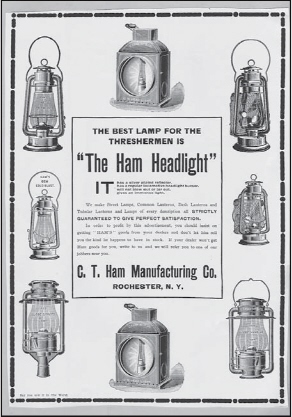

The kerosene lamp was an essential part of rural life until the coming of electric power. Various companies produced them, but one that gained attention from most farmers and thresher-men was the line from C.T. Ham Manufacturing Co. Thresher-men were familiar with the Ham Headlight for steam-traction engines; these are now a valuable collector’s item, often in the $100-plus category. Other styles included the Cold Blast Lantern or the Globe Hanging Lamp. Fortunate indeed was the rural town with a few Ham Globe Street Lamps on its main street.

Few early farms had a lawn mower; cattle or sheep grazed near the house, with the garden being fenced and off-limits. However, an 1889 advertisement illustrates the New Model, being the latest lawn mower from Chadborn & Coldwell Manufacturing Co. Later on, Coldwell gained fame for its early power lawn mowers.

Grist mills of some sort were frequently found on the farm, although most rural folks preferred taking some of their grain to a local miller for conversion into household corn meal and flour. This unnamed mill, of about 1910, was designed to grind everything from nuts to corn meal, being supplied with different grinding plates for various commodities. The ornate iron-work is typical of the period.

Aside from the ordinary kraut cutters usually found in antique shops, some companies made larger units, such as the Buffalo Kraut Cutter of 1909. This one was produced by John E. Smith’s Sons Co., Buffalo, N.Y. This company also made meat and vegetable cutters, potato chip cutters, horse radish graters and other equipment.

North River Agricultural Works at New York included this special sugar mill in its 1866 catalog. Its description notes that it was used by “country dealers for crushing and preparing sugar for use; by which process damp and hard portions are crushed and disintegrated and made to look light and uniform in appearance.”

One Minute Manufacturing Co., Newton, Iowa, offered its Ice-less Refrigerator about 1910. A pit was dug beneath the unit; by means of a self-contained winch, the refrigerator shelves were lowered into the cool ground. When anything was needed, the unit was hoisted to the top, appearing in the glass door, as shown.

In the 1890s, Zimmerman Fruit Dryer Co., Cincinnati, advertised its Fruit and Vegetable Dryer and Baker, with the No. 1 Small unit being pictured here. By this time, the company had sold more than 10,000 of these units. The shelves could be loaded with the desired fruits or vegetables and a small fire beneath the unit took care of dehydration. Dried apples for example, were a favorite treat among many rural families.