49c Use signal phrases to integrate sources.

Whenever you include a paraphrase, summary, or direct quotation of another writer’s work in your paper, prepare your readers for it with introductory words called a signal phrase. A signal phrase usually names the author of the source and provides some context for the source material—such as the author’s credentials—and helps readers distinguish your ideas from those of the source.

When you write a signal phrase, choose a verb that fits with the way you are using the source. Are you, for example, using the source to support a claim or refute a belief?

WEAK VERB

Lorrine Goodwin, a food historian, says, “ . . . ”

STRONGER VERB (MLA)

Lorrine Goodwin, a food historian, rejects the claim: “ . . . ”

STRONGER VERB (APA)

Lorrine Goodwin, a food historian, has rejected the claim: “. . . ”

NOTE: MLA style calls for using verbs in the present or present perfect tense (argues, has argued) to introduce source material unless you include a date that specifies the time of the original author’s writing. APA style calls for using verbs in the past tense or present perfect tense (explained, has explained) to introduce source material. In APA style, use the present tense only for discussing the applications or effects of your own results (the data suggest) or knowledge that has been clearly established (researchers agree).

Using signal phrases in APA papers

To avoid monotony, try to vary both the language and the placement of your signal phrases.

Model signal phrases

In the words of Mitra (2013), “. . .”

Bell (2010) has noted that. . .

Donista-Schmidt and Zuzovsky (2014) pointed out that . . .

“. . . ,” claimed Çubukçu (2012, Introduction section).

Horn and Staker (2011) have offered a compelling argument for this view: “. . .”

Verbs in signal phrases

|

admitted |

contended |

pointed out |

|

agreed |

declared |

reasoned |

|

argued |

denied |

refuted |

|

asserted |

emphasized |

rejected |

|

believed |

explained |

reported |

|

claimed |

insisted |

responded |

|

compared |

noted |

suggested |

|

confirmed |

observed |

wrote |

Marking boundaries

Readers need to move smoothly from your words to the words of a source. Avoid dropping a quotation into the text without warning. Provide a clear signal phrase, including at least the author’s name, to indicate the boundary between your words and the source’s words. The signal phrase is highlighted in the second example. (MLA is shown below; for APA, see 53b.)

DROPPED QUOTATION

Laws designed to prevent chronic disease by promoting healthier food and beverage consumption also have potential economic benefits. “[A] 1% reduction in the intake of saturated fat across the population would prevent more than 30,000 cases of coronary heart disease annually and would save more than a billion dollars in health care costs” (Nestle 7).

QUOTATION WITH SIGNAL PHRASE

Laws designed to prevent chronic disease by promoting healthier food and beverage consumption also have potential economic benefits. Marion Nestle, New York University professor of nutrition and public health, notes that “a 1% reduction in the intake of saturated fat across the population would prevent more than 30,000 cases of coronary heart disease annually and would save more than a billion dollars in health care costs” (7).

Establishing authority

The first time you mention a source, include in the signal phrase the author’s title, credentials, or experience to help your readers recognize the source’s authority and your own credibility (ethos) as a responsible researcher who has located reliable sources. Signal phrases are highlighted in the next two examples. (MLA is shown below; for APA, see 53b.)

Text reads as follows,

Source with no Credentials

Michael Pollan notes that open quotes [t]he Centers for Disease Control estimates that fully

three quarters of U S health care spending goes to treat chronic diseases, most of which are preventable and linked to diet: heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and at least a third of all cancers. Close quotes. [The phrase ‘Michael Pollan notes’ is highlighted. [A corresponding margin note reads, ‘Readers aren’t given clues about the author’s authority.’].

Source with Credentials

Journalist Michael Pollan, who has written extensively about Americans’ unhealthy eating habits, notes that open quotes [t]he Centers for Disease Control estimates that fully three quarters of U S health care spending goes to treat chronic diseases, most of which are preventable and linked to diet: heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and at least a third of all cancers. Close quotes. [The phrase ‘Journalist Michael Pollan, who has written extensively about Americans’ unhealthy eating habits, notes’ is highlighted, and a corresponding margin note reads, ‘The author’s credibility is suggested in the signal phrase.’].

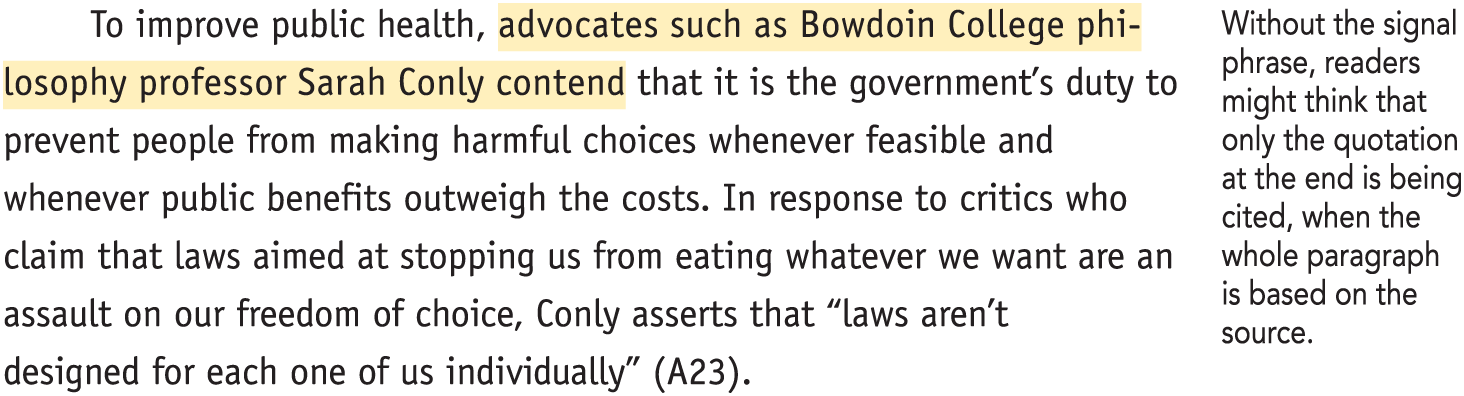

Introducing summaries and paraphrases

Introduce most summaries and paraphrases with a signal phrase that names the author and places the material in the context of your argument. Readers will then understand that everything between the signal phrase and the parenthetical citation summarizes or paraphrases the cited source. (MLA is shown below; for APA, see 53b.)

Text reads as follows:

To improve public health, advocates such as Bowdoin College philosophy

professor Sarah Conly contend that it is the government’s duty to [The phrase ‘advocates such as Bowdoin College philosophy professor Sarah Conly contend’ is highlighted, and the corresponding margin note reads, ‘Without the signal phrase, readers might ‘prevent people from making harmful choices whenever feasible and whenever public benefits outweigh the costs. In response to critics who claim that laws aimed at stopping us from eating whatever we want are an assault on our freedom of choice, Conly asserts that open quotes laws aren’t designed for each one of us individually close quotes (A23).’ [A corresponding margin note reads, ‘think that only the quotation at the end is being cited, when the whole paragraph is based on the source.’]

There are times, however, when a summary or a paraphrase does not require a signal phrase naming the author. When the context makes clear where the cited material begins, you may omit the signal phrase and include the author’s last name in parentheses.

Integrating statistics and other facts

When you cite a statistic or another specific fact, a signal phrase is often not necessary. Readers usually will understand that the citation refers to the statistic or fact and not the whole paragraph.

Seventy-five percent of Americans are opposed to laws that restrict or put limitations on access to unhealthy foods (Neergaard and Agiesta).

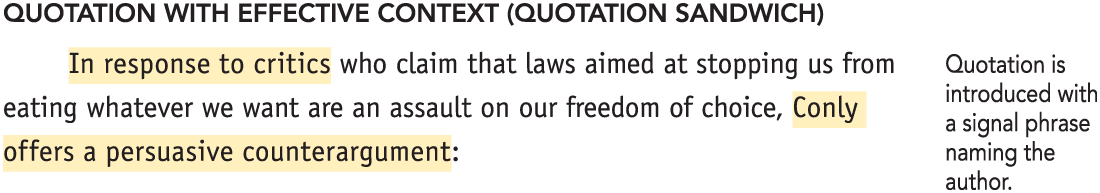

Putting source material in context

Readers should not have to guess why source material appears in your paper. A signal phrase can help you connect your own ideas and those of another writer by clarifying how the source will contribute to your paper.

If you use another writer’s words, you must explain how they relate to your argument. Quotations don’t speak for themselves; you must create a context for readers. Sandwich each quotation between sentences of your own, introducing the quotation with a signal phrase and following it with interpretive comments that link the quotation to your paper’s argument. (MLA is shown below; for APA, see 53b.)

Text reads as follows:

Quotation with Effective Context (Quotation Sandwich)

In response to critics who claim that laws aimed at stopping us from eating whatever we want are an assault on our freedom of choice, Conly offers a persuasive counterargument: [The words ‘In response to critics,’ and ‘Conly offers a persuasive Counterargument’ are highlighted, and the corresponding margin note reads, Quotation is introduced with a signal phrase naming the author.]

Text reads as follows:

[L] aws aren’t designed for each one of us individually. Some of us can drive safely at 90 miles per hour, but we’re bound by the same laws as the people who can’t, because individual speeding laws aren’t practical. Giving up a little liberty is something we agree to when we agree to live in a democratic society that is governed by laws. (A 23).’ [A corresponding margin note reads, Long quotation is set off from the text; quotation marks are omitted.]

As Conly suggests, we need to change our either/or thinking (either we have complete freedom of choice or we have government regulations and lose our freedom) and instead need to see health as a matter of public good, not individual liberty. [The words, ‘As Conly suggests, we need to change our either/or thinking’ are highlighted, and a corresponding margin note reads Quotation is followed by analytical comments that connect the source to the student’s argument.]

Using sentence guides to integrate sources

You build your credibility (ethos) by accurately representing the ideas of others and by integrating these ideas into your paper. An important way to present the ideas of others before agreeing or disagreeing with them is to use sentence guides. These guides act as academic sentence starters; they show you how to use signal phrases in sentences to make clear to your reader whose ideas you’re presenting—your own or those you have encountered in a source.

Presenting others’ ideas. As an academic writer, you will be expected to demonstrate your understanding of a source by summarizing the views or arguments of its author. The following language will help you to do so:

X argues that

X and Y emphasizes the need for .

NOTE: The examples in this box are shown in MLA style. If you were writing in APA style, you would include the year of publication after the source’s name and typically use past tense or present perfect tense (emphasized or has emphasized).

Presenting direct quotations. To introduce the exact words of a source because their accuracy and authority are important for your argument, you might try phrases like these:

X describes the problem this way: “”

Y argues in favor of the policy, pointing out that “.”

Presenting alternative ideas. At times you will have to synthesize the ideas of multiple sources before you introduce your own.

While X and Y have asked an important question, Z suggests that we should be asking a different question: .

X has argued that Y’s research findings rest upon questionable assumptions and .

Presenting your own ideas by agreeing or extending. You may agree with the author of a source but want to add your own voice to extend the point or go deeper. The following phrases could be useful:

X’s argument is convincing because .

Y claimed that . But isn’t it also true that ?

Presenting your own ideas by disagreeing and questioning. College writing assignments encourage you to show your understanding of a subject but also to question or challenge ideas and conclusions about the subject. This language can help:

X’s claims about are misguided.

Y insists that , but perhaps she is asking the wrong question.

Presenting and countering objections to your argument. To anticipate objections that readers might make, try the following sentence guides:

Not everyone will endorse this argument; some may argue instead that .

Some will object to this proposal on the grounds that .