51b Sample MLA research paper

On the following pages is a research paper on the topic of the role of government in legislating food choices, written by Sophie Harba, a student in a composition class. Harba’s paper is documented with in-text citations and a list of works cited in MLA style. Annotations in the margins of the paper draw your attention to Harba’s use of MLA style and her effective writing.

Text on the top left portion of the page reads,

Sophie Harba

Professor Baros-Moon

Engl 1101

9 November 2018

What’s for Dinner? Personal Choices versus Public Health [A corresponding margin note reads, Title is centered]

Should the government enact laws to regulate healthy eating choices? [A corresponding margin note reads, Opening research question engages readers.] Many Americans would answer an emphatic open quotes No, close quotes arguing that what and how much we eat should be left to individual choice rather than unreasonable laws. Others might argue that it would be unreasonable for the government not to enact legislation, given the rise of chronic diseases that result from harmful diets. In this debate, both the definition of reasonable regulations and the role of government to legislate food choices are at stake. [A corresponding margin note reads, Writer highlights the research conversation.] In the name of public health and safety, state governments have the responsibility to shape health policies and to regulate healthy eating choices, especially since doing so offers a potentially large social benefit for a relatively small cost. [A corresponding margin note reads, Thesis answers the research question and presents Harba’s main point.]

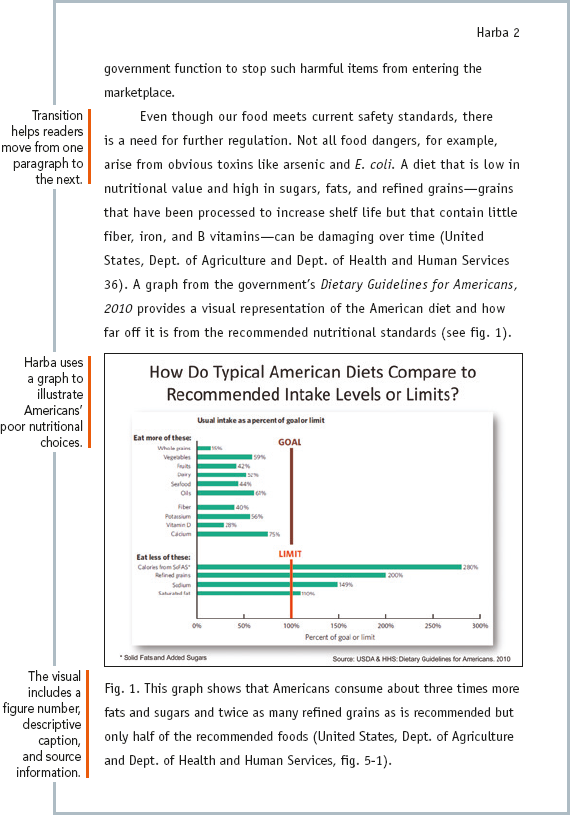

Debates surrounding the government’s role in regulating food have a long history in the United States. According to Lorine Goodwin, a food historian, nineteenth-century reformers who sought to purify the food supply were called open quotes fanatics close quotes and open quotes radicals close quotes by critics who argued that consumers should be free to buy and eat what they want (77). [A corresponding margin note reads, Signal phrase names the author. The parenthetical citation includes a page number.] Thanks to regulations, though, such as the 1906 federal Pure Food and Drug Act, food, beverages, and medicine are largely free from toxins. In addition, to prevent contamination and the spread of disease, meat and dairy products are now inspected by government agents to ensure that they meet health requirements. [A corresponding margin note reads, Historical background provides context.] Such regulations can be considered reasonable because they protect us from harm with little, if any, noticeable consumer cost. [A corresponding margin note reads, Harba explains her use of a key term, reasonable.] It is not considered an unreasonable infringement on personal choice that contaminated meat or arsenic-laced cough drops are unavailable at our local supermarket. Rather, it is an important [A corresponding margin note reads, Harba establishes common ground with the reader.]

Text below the annotated text reads, Marginal annotations indicate M L A-style formatting and effective writing.

Text continues as follows:

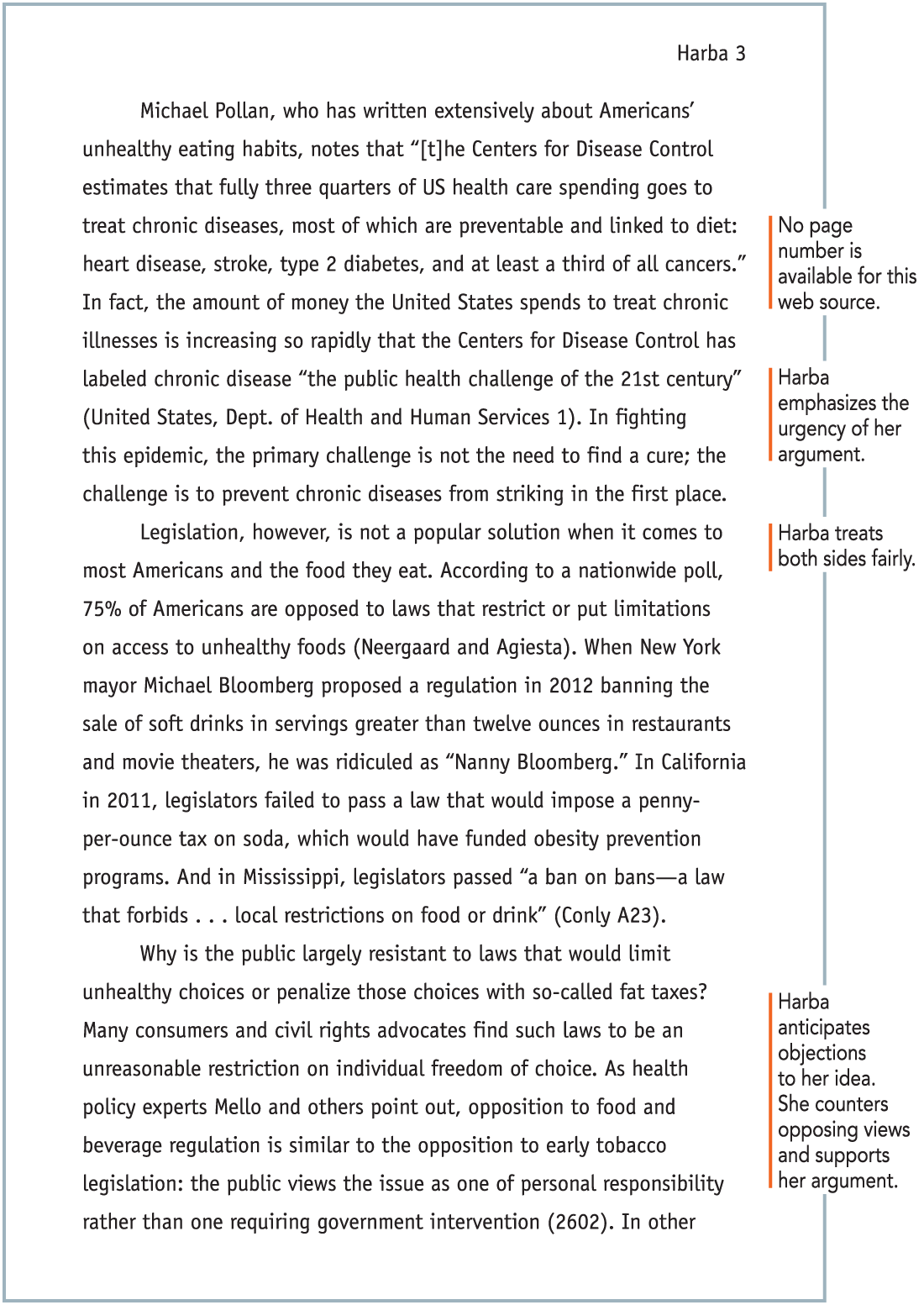

Michael Pollan, who has written extensively about Americans’ unhealthy eating habits, notes that open quotes [t]he Centers for Disease Control estimates that fully three quarters of US health care spending goes to treat chronic diseases, most of which are preventable and linked to diet: heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and at least a third of all cancers. close quotes In fact, the amount of money the United States spends to treat chronic illnesses is increasing so rapidly that the Centers for Disease Control has labeled chronic disease open quotes the public health challenge of the twenty first century close quotes (United States, Dept of Health and Human Services 1). [A corresponding margin note reads, No page number is available for this web source.] In fighting this epidemic, the primary challenge is not the need to find a cure; the challenge is to prevent chronic diseases from striking in the first place. [A corresponding margin note reads, Harba emphasizes the urgency of her argument.]

Legislation, however, is not a popular solution when it comes to most Americans and the food they eat. [A corresponding margin note reads, Harba treats both sides fairly.] According to a nationwide poll, 75 Percent of Americans are opposed to laws that restrict or put limitations on access to unhealthy foods (Neergaard and Agiesta). When New York mayor Michael Bloomberg proposed a regulation in 2012 banning the sale of soft drinks in servings greater than twelve ounces in restaurants and movie theaters, he was ridiculed as open quotes Nanny Bloomberg. close quotes In California in 2011, legislators failed to pass a law that would impose a penny per-ounce tax on soda, which would have funded obesity prevention programs. And in Mississippi, legislators passed open quotes a ban on bans m dash a law that forbids ellipsis local restrictions on food or drink close quotes (Conly A 23).

Why is the public largely resistant to laws that would limit unhealthy choices or penalize those choices with so-called fat taxes? Many consumers and civil rights advocates find such laws to be an unreasonable restriction on individual freedom of choice. As health policy experts Mello and others point out, opposition to food and beverage regulation is similar to the opposition to early tobacco legislation: the public views the issue as one of personal responsibility rather than one requiring government intervention (2602). In other [A corresponding margin note reads, Harba anticipates objections to her idea. She counters opposing views and provides support for her argument.]

The text continues as follows:

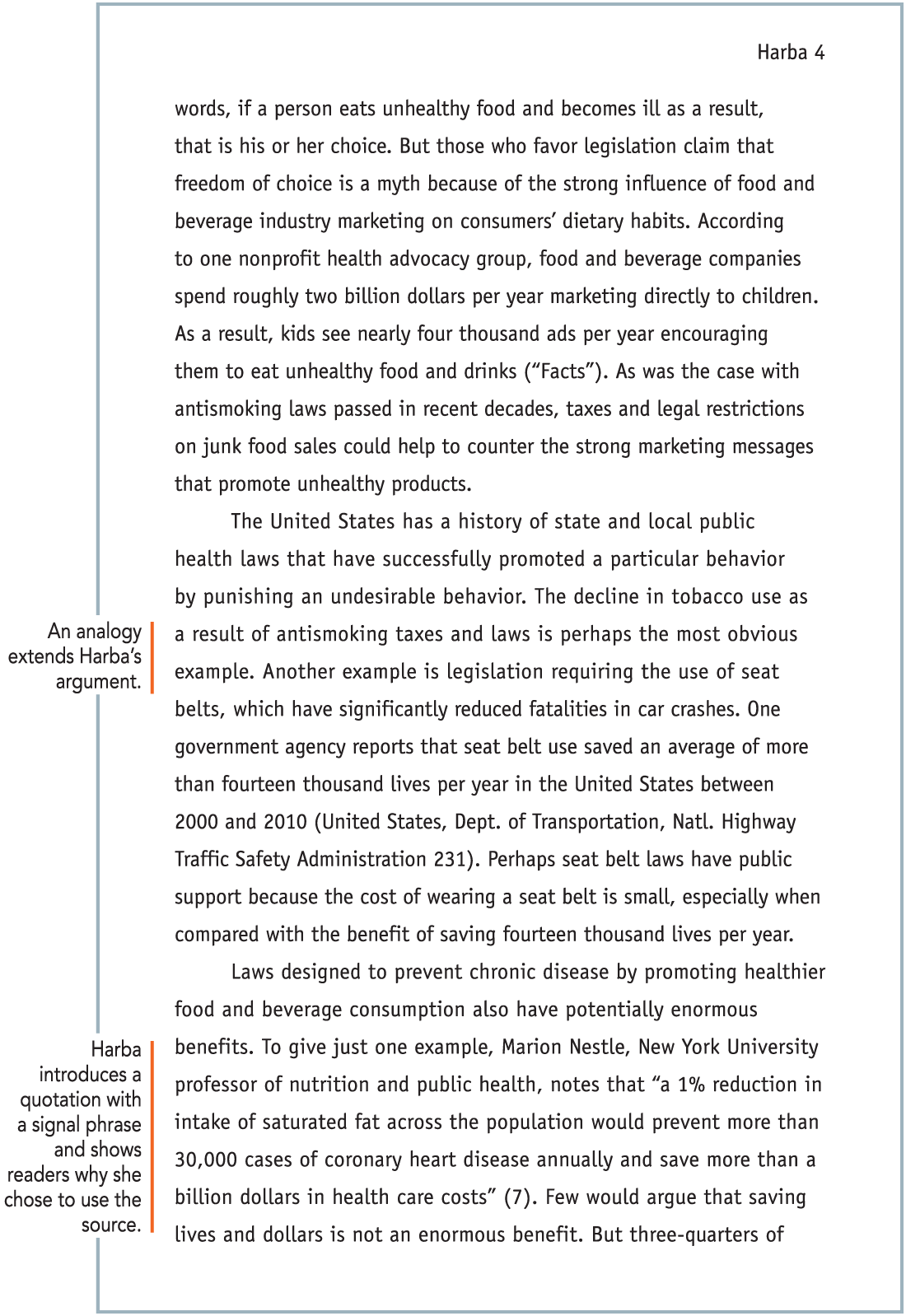

words, if a person eats unhealthy food and becomes ill as a result, that is his or her choice. But those who favor legislation claim that freedom of choice is a myth because of the strong influence of food and beverage industry marketing on consumers’ dietary habits. According to one nonprofit health advocacy group, food and beverage companies spend roughly two billion dollars per year marketing directly to children. As a result, kids see nearly four thousand ads per year encouraging them to eat unhealthy food and drinks (open quotes Facts close quotes). As was the case with antismoking laws passed in recent decades, taxes and legal restrictions on junk food sales could help to counter the strong marketing messages that promote unhealthy products.

The United States has a history of state and local public health laws that have successfully promoted a particular behavior by punishing an undesirable behavior. The decline in tobacco use as a result of antismoking taxes and laws is perhaps the most obvious example. Another example is legislation requiring the use of seat belts, which have significantly reduced fatalities in car crashes. [A corresponding margin note reads, An analogy extends Harba’s argument.] One government agency reports that seat belt use saved an average of more than fourteen thousand lives per year in the United States between 2000 and 2010 (United States, Dept of Transportation, Natl. Highway Traffic Safety Administration 231). Perhaps seat belt laws have public support because the cost of wearing a seat belt is small, especially when compared with the benefit of saving fourteen thousand lives per year.

Laws designed to prevent chronic disease by promoting healthier food and beverage consumption also have potentially enormous benefits. To give just one example, Marion Nestle, New York University professor of nutrition and public health, notes that open quotes a 1Percent reduction in intake of saturated fat across the population would prevent more than 30,000 cases of coronary heart disease annually and save more than a billion dollars in health care costs close quotes (7). Few would argue that saving lives and dollars is not an enormous benefit. But three-quarters of [A corresponding margin note reads, Harba introduces a direct quotation with a signal phrase and follows with a comment that shows readers why she chose to use the source.]

Text continues as follows:

Americans say they would object to the costs needed to achieve this benefit m dash the regulations needed to reduce saturated fat intake.

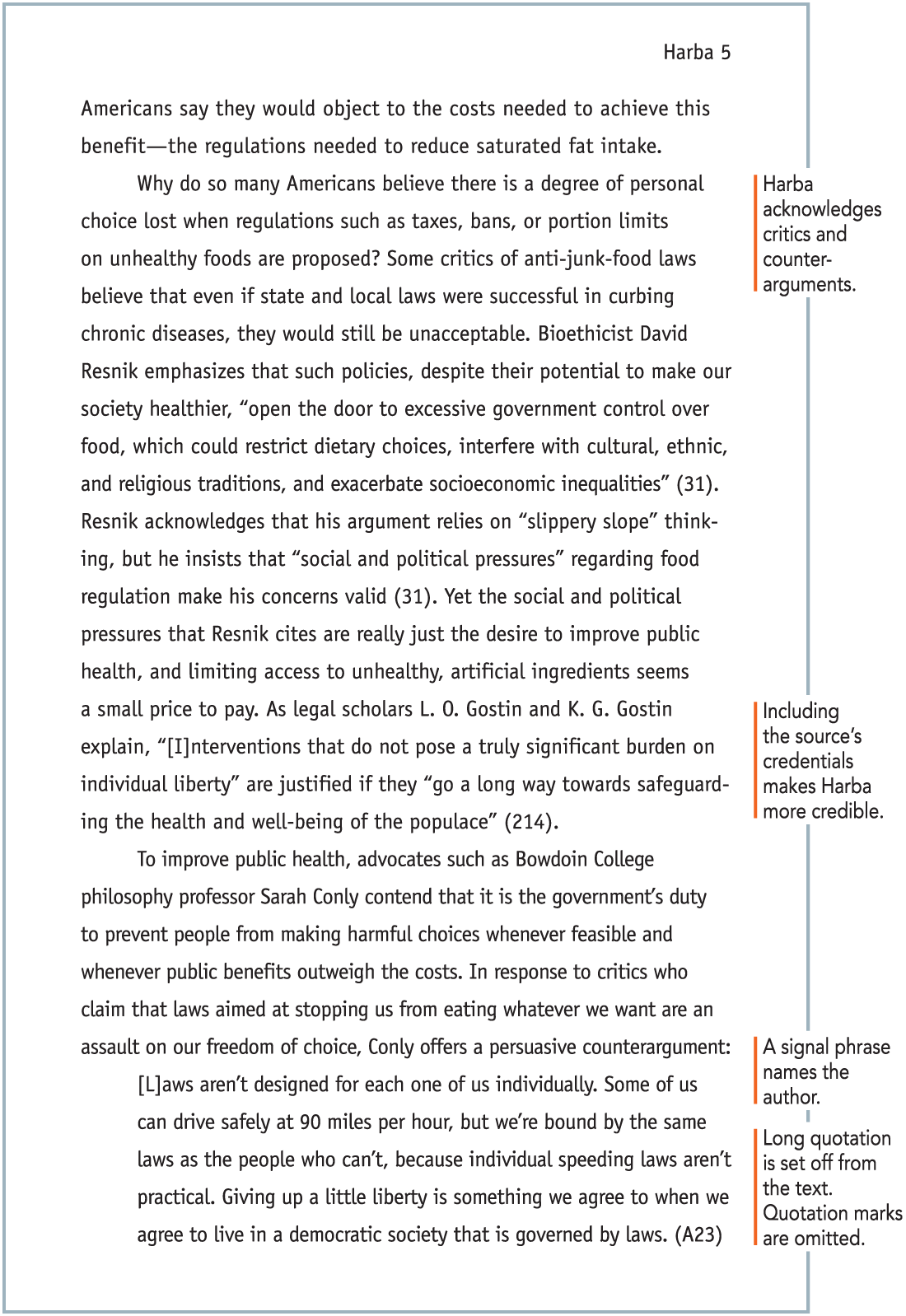

Why do so many Americans believe there is a degree of personal choice lost when regulations such as taxes, bans, or portion limits on unhealthy foods are proposed? Some critics of anti-junk-food laws believe that even if state and local laws were successful in curbing chronic diseases, they would still be unacceptable. Bioethicist David Resnik emphasizes that such policies, despite their potential to make our society healthier, open quotes open the door to excessive government control over food, which could restrict dietary choices, interfere with cultural, ethnic, and religious traditions, and exacerbate socioeconomic inequalities close quotes (31). Resnik acknowledges that his argument relies on open quotes slippery slope close quotes thinking, but he insists that open quotes social and political pressures close quotes regarding food regulation make his concerns valid (31). [A corresponding margin note reads, Harba acknowledges critics and counterarguments.] Yet the social and political pressures that Resnik cites are really just the desire to improve public health, and limiting access to unhealthy, artificial ingredients seems a small price to pay. As legal scholars L O Gostin and K G Gostin explain, open quotes [I]nterventions that do not pose a truly significant burden on individual liberty close quotes are justified if they open quotes go a long way towards safeguarding the health and well-being of the populace close quotes (214). [A corresponding margin note reads, Including the source’s credentials makes Harba more credible.]

To improve public health, advocates such as Bowdoin College philosophy professor Sarah Conly contend that it is the government’s duty to prevent people from making harmful choices whenever feasible and whenever public benefits outweigh the costs. In response to critics who claim that laws aimed at stopping us from eating whatever we want are an assault on our freedom of choice, Conly offers a persuasive counterargument: [A margin note reads, A signal phrase names the author.]

[L]aws aren’t designed for each one of us individually. Some of us can drive safely at 90 miles per hour, but we’re bound by the same laws as the people who can’t, because individual speeding laws aren’t practical. Giving up a little liberty is something we agree to when we agree to live in a democratic society that is governed by laws. (A 23) [A corresponding margin note reads, Long quotation is set off from the text. Quotation marks are omitted.]

Text continues as follows:

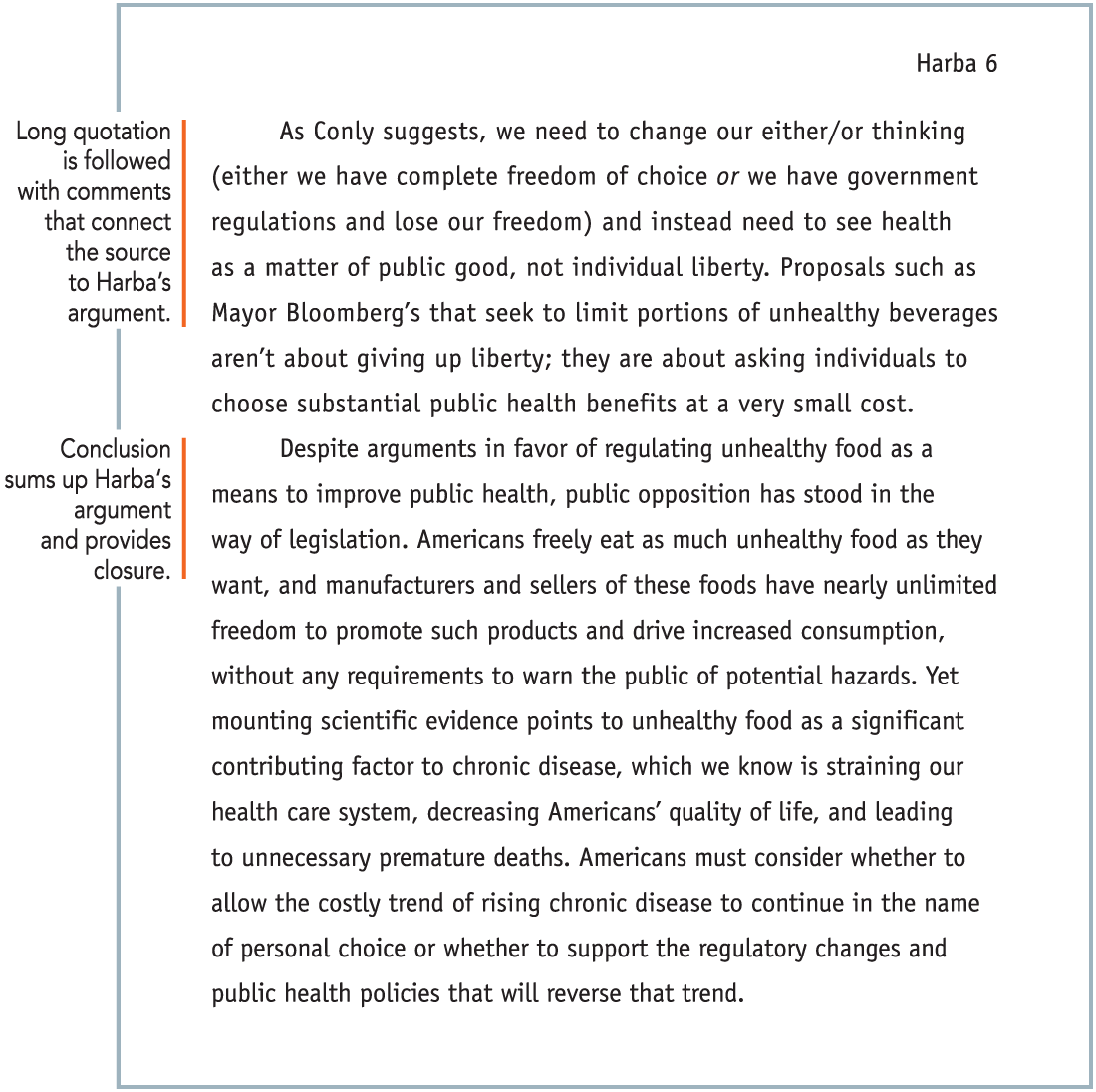

As Conly suggests, we need to change our either/or thinking (either we have complete freedom of choice or we have government regulations and lose our freedom) and instead need to see health as a matter of public good, not individual liberty. Proposals such as Mayor Bloomberg’s that seek to limit portions of unhealthy beverages aren’t about giving up liberty; they are about asking individuals to choose substantial public health benefits at a very small cost. [A corresponding margin note reads, Long quotation is followed with comments that connect the source to Harba’s argument.]

Despite arguments in favor of regulating unhealthy food as a means to improve public health, public opposition has stood in the way of legislation. Americans freely eat as much unhealthy food as they want, and manufacturers and sellers of these foods have nearly unlimited freedom to promote such products and drive increased consumption, without any requirements to warn the public of potential hazards. Yet mounting scientific evidence points to unhealthy food as a significant contributing factor to chronic disease, which we know is straining our health care system, decreasing Americans’ quality of life, and leading to unnecessary premature deaths. Americans must consider whether to allow the costly trend of rising chronic disease to continue in the name of personal choice or whether to support the regulatory changes and public health policies that will reverse that trend. [A corresponding margin note reads, Conclusion sums up Harba‘s argument and provides closure.]

Text reads as follows:

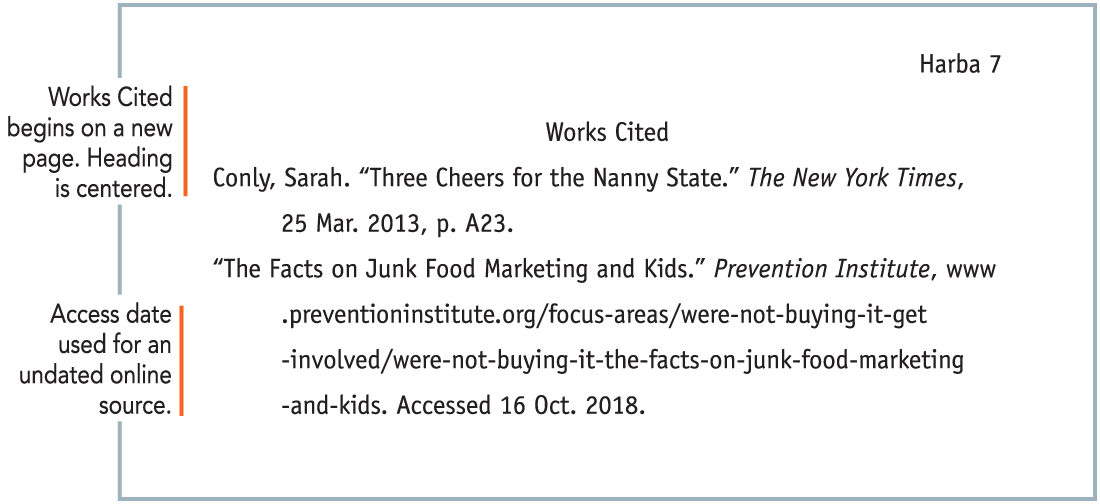

Works Cited [A margin note reads, Heading is centered.]

Conly, Sarah. Open quotes Three Cheers for the Nanny State. Close quotes [italics] The New York Times [end italics], 25 March 2013, p A 23.

Open quotes The Facts on Junk Food Marketing and Kids. Close quotes Prevention

Institute, w w w dot prevention institute dot org forward slash focus hyphen areas forward slash were hyphen not hyphen buying hyphen it hyphen get hyphen involved forward slash were hyphen not hyphen buying hyphen it hyphen the hyphen facts hyphen on hyphen junk hyphen food hyphen marketing hyphen and hyphen kids. Accessed 16 October 2018. [A margin note reads, List is Alphabetized by authors last names (or by title if no author)]

BasicInstinct. (2015, December 4). Re: U S economy added 211,000 jobs in November;

unemployment rate holds at 5 percent [Comment]. [italics] The Washington Post [end italics]. Retrieved from h t t p colon forward slash forward slash Washington post dot com forward slash.

‘Basic Instinct’ is labeled screen name. ‘2015, December 4’ is labeled year plus month plus day (daily publication). ‘U S economy added 211,000 jobs in November; unemployment rate holds at 5 percent’ is labeled title of original article ‘Comment’ is labeled label. ‘The Washington Post’ is labeled title of publication and the web address is labeled U R L for web publication.

Text reads as follows:

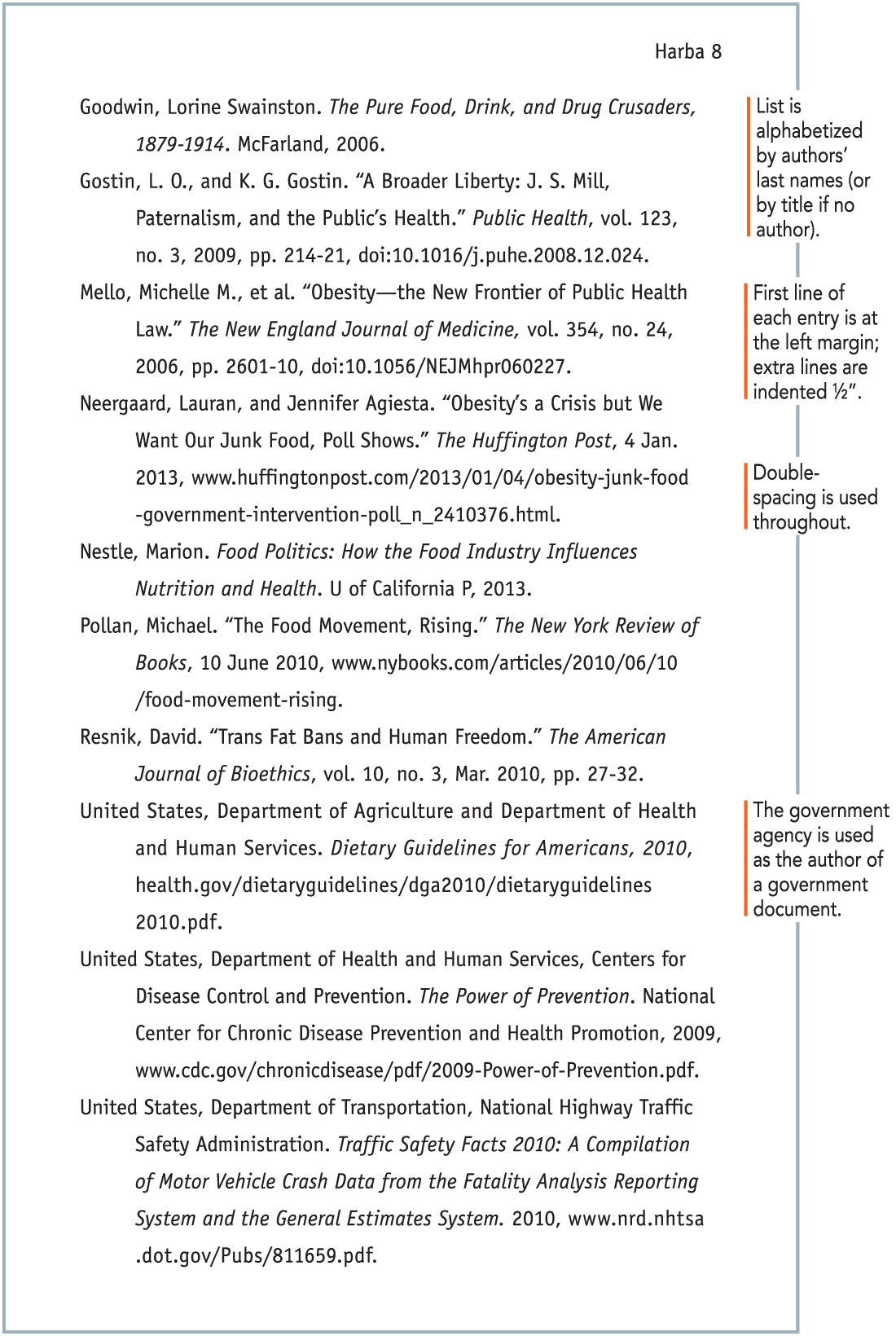

Goodwin, Lorine Swainston. The Pure Food, Drink, and Drug Crusaders, 1879 to

1914. McFarland, 2006.

Gostin, L O, and K G Gostin. Open quotes A Broader Liberty: J S Mill,

Paternalism, and the Public’s Health. Close quotes [italics] Public Health [end italics], volume 123, number 3, 2009, p p 214 to 21, d o i: 10.1016/j dot p u h e dot 2008 dot 12 dot 0 2 4. [A corresponding margin note reads, Access date used for an online source that has no update date.]

Mello, Michelle M, et alia Open quotes Obesity m dash the New Frontier of Public Health

Law. close quotes [italics] The New England Journal of Medicine [end italics], volume 354, number 24, 2006, p p. 2601 to 10, d o i: 10.1056/N E J M h p r 0 6 0 2 2 7. [A corresponding margin note reads, First line of each entry is at the left margin; extra lines are indented one by two inch.]

Neergaard, Lauran, and Jennifer Agiesta. Open quotes Obesity’s a Crisis but We

Want Our Junk Food, Poll Shows. Close quotes [italics] The Huffington Post [end italics], 4 January 2013, w w w dot huffington post dot com forward slash 2013 forward slash 01 forward slash 04 forward slash obesity hyphen junk hyphen food hyphen government hyphen intervention hyphen poll underscore n underscore 2 4 1 0 3 7 6 dot h t m l. [A corresponding margin note reads, Double spacing is used throughout.]

Nestle, Marion. [italics] Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition andHealth [end italics]. U of California P, 2013.

Pollan, Michael. Open quotes The Food Movement, Rising. Close quotes [italics]The New York Review of Books [end italics], 10 June 2010, w w w dot n y books dot com forward slash articles forward slash 2010 forward slash 06 forward slash 10 forward slash food hyphen movement hyphen rising.

Resnik, David. Open quotes Trans Fat Bans and Human Freedom. close quotes [italics] The American Journal of Bioethics [end italics], volume 10, number 3, March 2010, p p 27 to 32.

United States, Department of Agriculture and Department of Health and Human

Services. [italics] Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010 [end italics], health dot g o v forward slash dietary guidelines forward slash d g a 2010 forward slash dietary guidelines 2010 dot p d f. [A corresponding margin note reads, The government agency is used as the author of a government document.]

United States, Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention. [italics] The Power of Prevention [end italics]. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2009, w w w dot c d c dot g o v forward slash chronic disease forward slash p d f forward slash 2009 hyphen Power hyphen of hyphen prevention dot p d f.

United States, Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety

Administration. [italics] Traffic Safety Facts 2010: A Compilation of Motor Vehicle Crash Data from the Fatality Analysis Reporting System and the General Estimates System. 2010 [end italics], w w w dot n r d dot n h t s a dot d o t dot g o v forward slash Pubs forward slash 8 1 1 6 5 9 dot p d f.