PETER GLANCY

Apart from the obligatory trip to St Paul’s, glowing in its wonderful tercentenary cleaning, and the less obligatory visit to the Museum of London, few tourists spend much time in the City. The more daring may pop into a Wren church or two, or even, for the positively adventurous, the Bank of England Museum, but generally visitors steer clear. Their loss! There is much to see in the City and the most exciting time to take it all in is at night. This may seem perverse, as everything will be closed, but then that is all to the good. The bankers and City workers are making their way home. The City is slowly emptying and is yours to enjoy in peace.

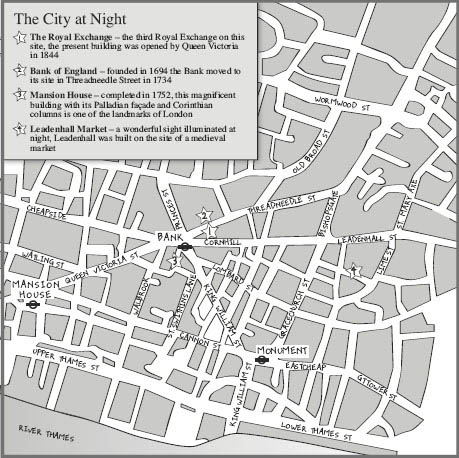

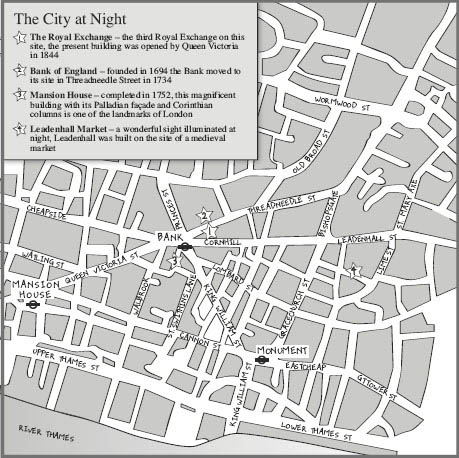

The Royal Exchange and the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street

STAND IN THE open space before the Royal Exchange after, say, seven o’clock in the evening and you will feel the life force draining away as the City workers pour down into the Underground, hop on to the buses, flag down a taxi or pop into a watering hole for a last snifter before winding off home. As the buildings start to light up they take on a sort of majesty (even an indifferent building can look impressive illuminated) and somehow the hard reality of the present bleeds away to reveal the magic of the past. And what a past! Empty alleys seem to carry this history more potently at night when they’ve ceased to carry the bankers. After all, this City is 2,000 years old!

Of course there has been fire, Blitz and general bloody-minded messing about, but there are treasures to find. Take the Royal Exchange itself (a wonderful cleaning job), which goes back to the days of Good Queen Bess. A City merchant Thomas Gresham, having travelled on the continent and seen the great trading Bourses of Europe, was dismayed to find business in London carried out on the streets. He created the Exchange here paying for the enterprise out of his own pocket and the Queen opened it, naming it ‘the Royal Exchange’. (Look at the portico to find her name on the left.) Of course, the building went down in the Great Fire of 1666 when all the statues of the kings and queens were shattered, leaving just Gresham’s statue intact. The new building lasted a century and a half before also burning down in the not-so-great fire of 1838. It was so cold that day that the water in the city’s pipes froze and the building was completely lost. So what we see today is the third building, by William Tite, and I suspect it may be the best of them all. Look up to see Victoria’s name on the right; she opened it in 1844. It’s open in the evening so do wander in, it’s quite spectacular! Pop round the back, too, and you’ll find two wonderful old gas lamps fizzing into life. Nothing at night brings back the past like gas lighting, and we’ve held on to around 2,000 of these old lamps.

WHERE TO READ THIS

The City pubs at night are maybe a little noisy and vibrant to get to grips with reading. But for a spectacular place to settle try the magnificent mid-nineteenth-century neoclassical interior of the Royal Exchange. Or for a cosier read, and a wonderful choice of wines, try the Olde Wine Shades just off Cannon Street down the hill on Martin Lane. The cellars here used to be connected to the river and were reputedly used by smugglers.

West of this grand facade stands that Old Lady of Threadneedle Street, the Bank of England. This is actually two buildings, like a double-decker bus: one below, one up top. The lower half of 1788 is by that eccentric maverick John Soane, but in the 1920s the decision was taken to mostly demolish the original building and extend the building upwards into a sort of chateau, leaving only Soane’s fortress-like curtain wall. The great architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner wrote that ‘the virtual rebuilding of the Bank of England in 1921–37, in spite of the Second World War, was the worst individual loss suffered by London architecture in the first half of the twentieth century’. I certainly agree, as there is so little left of this magnificent architect, who gave us our first public art gallery (which still delights visitors in Dulwich).

For many years there was a terrific nightly scene at the bank when a Brigade of Guards, known as the Bank Piquet, marched through the streets of the City to pipe and drum. They stopped the traffic as they went. This must have been a glorious night-time scene as they ceremoniously approached the Bank. It continued right up until 1973 when the threat of invasion seemed less likely than in the terrifying days of the Gordon Riots back in 1780. Incidentally, if you are lucky enough to get your hands on a £50 note turn it over for a picture of the first governor of the bank Sir John Houblon, an Huguenot of French descent.

Demolition began on a clutch of seven buildings opposite the Exchange in 1988, their listed-building status and the intercession of the Prince of Wales not being enough to save them from the bulldozers. The Mappin and Webb building was the saddest loss and I remember going down to say a fond farewell the day before demolition began. Now there is the massive, post-modernist, pink hulk of James Stirling’s Number One Poultry. The clock tower supports a viewing platform which pops out either side like a pair of tiny ineffectual wings. To the south of this slice of a set for Miami Vice stands the Mayor’s Nest, or more properly the Mansion House in Mansion House Place. This is the official residence of the Lord Mayor and one of the first buildings to be spectacularly illuminated at night. It’s by George Dance and dates to the mid-eighteenth century. Inside there is a Justice Room for when the Lord Mayor acts as the City’s Chief Magistrate and there are ten cells for men and (rather like the public loos, ladies) only one for women. Known as the Birdcage, this once housed Emmeline Pankhurst, that formidable campaigner for Votes For Women. On an even more eccentric note it also houses a gold telephone, the millionth to be made, giving it a curious connection with the wonderful church of St Stephen at 39 Walbrook right beside. This church contains the phone that took the first distress call made to the world’s first hotline for ‘suicidal and despairing people’. The year was 1953, the number was Mansion House 9000 and the organisation was the Samaritans, set up by the remarkable rector Chad Varah, who died in 2007 aged in his nineties. BT awarded the five-millionth London phone line as a free line to the Samaritans and this 1970s set remains in the church, both it and the original black phone presented as precious relics in display cases. Another precious object, sitting under Wren’s dome, is the altar in Italian marble, which is a late work by the great Henry Moore. Beautiful as it is, Londoners have cheekily nicknamed it ‘the Camembert Cheese’.

A strange night scene that took place outside this church many years ago had its beginnings in Italy. Soaking up the sun, and architecture, on his Grand Tour, Lord Burlington, that arch-Palladian and arbiter of eighteenth-century taste, came across a local enthusing about St Stephen’s church. ‘To think that you have come all this way and yet you have the most beautiful building in the world in London.’ Burlington didn’t know the church and immediately on his return to England made a beeline to the City to acquaint himself. Unfortunately it was the middle of the night, but that didn’t deter him from knocking up the churchwarden, who was dumbfounded by this madman insisting on his unlocking the door. Burlington explored by torchlight tingling with excitement. Like a child on Christmas morning, he was back at dawn to explore by daylight.

These wonderful buildings survived the Blitz because of a curious, and tragic, twist of fate. What happened? Well take a look down nearby Lombard Street and you’ll see another treasure, the church of St Mary Woolnoth (on the corner of Lombard and King William Streets) by Hawksmoor. This stands over the Northern Line underground station, the construction of which saw the destruction of the church’s crypt. During the Blitz a bomb fell in front of the Exchange, rolled towards the church and found itself somehow being carried down on the escalator to the platform, where it exploded, killing the people sheltering there and leaving the beautiful buildings above intact, for that night at least. A bitter survival indeed!

Up close – the City at Night

When the bombs rained down on London in the Blitz they not only destroyed but revealed! Many strange sights can be seen in the City that are the result of the destruction. If you decided to pop into the Olde Wine Shades you’ll see one of these curiosities. On the side wall is a curious rusting cupboard which puzzles everybody who walks past it. It is, in fact, a safe that was once set into an internal wall and now eccentrically braves the elements.

The narrow lane opposite is St Swithin’s Lane; long and thin, it almost seems to suck you down. You’ll wonder why you bothered when you reach the bottom and the ugly mass of Cannon Street station faces you, but on the right is something quite astonishing, so remarkable, in fact, that people walk past it without so much as a second glance. But at night it’s harder to ignore – a fan of light on the pavement blazing from a grille, behind which is the almost mythical London Stone. In Act 4, Scene 6 of Harry VI (Henry VI, Part 2) Shakespeare writes:

London, Cannon Street. Enter Jack Cade and the rest, and strikes his staff on the London stone.

Cade: Now is Mortimer lord of this city. And here, sitting upon London Stone, I charge and command that, of the city’s cost, the pissing conduit run nothing but claret wine this first year of our reign. And now henceforward it shall be treason for any that calls me other than Lord Mortimer.

And just to show that he’s not joking, when a soldier runs in shouting, ‘Jack Cade, Jack Cade,’ he has him killed on the spot, announcing, rather unnecessarily, that he won’t be doing that again.

Legend says the stone arrived in the city when a magician flew to Earth on it, although it’s more likely to be part of a Roman building left lying around. At some point it became embedded in the church of St Swithin that then became known as St Swithin London Stone. The church was destroyed in the Blitz and not restored, so now the Stone is embedded in a rather dull office block. Cannon Street, by the way, gets its odd name from the candlewick makers who lived and worked here. If you look around you might find a plaque or two denoting the Ward of Candlewick, but sadly no longer any candlewick makers.

Where the City truly releases its magic at night-time is in a clutch of buildings that thrillingly display past and present as nowhere else. South of Leadenhall Street between Gracechurch and Lime Street is a building that is impossible not to put a smile on your face and a flash of recognition – Leadenhall Market. When Hagrid sets off with Harry in the first Harry Potter film to buy his wand, the journey begins here. The building reminds me of all the great shopping arcades of the northern industrial towns where I hail from. Illuminated at night like some huge film set (it also saw John Wayne scrapping in a late film Brannigan), it stands on the site of a medieval market. A document of 1345 stipulated that strangers (non-Londoners) must bring their poultry to Leadenhall and Londoners theirs to Westcheap. Underneath Leadenhall Market is the Roman forum of Londinium. It’s thrilling to think that some of that ancient structure lies trapped beneath at a depth of about twenty feet.

Standing cheek by jowl to the Market is something spectacularly different, but equally magical. This is the astonishing Lloyd’s Building, 1 Lime Street, a staggering building that is nothing less than sensational when illuminated in blue light at night. It resembles a huge set for Blade Runner, or a sort of futuristic fairy-tale castle. I love this building with its exposed pipes like modernist turrets and its lifts hurtling up and down the outside of the building offering ever-changing views of the city. A perfect backdrop to the bizarre chase of giant teddy bears and Emma Peel, times two, in The Avengers film. And to think that it all began in a seventeenth-century coffee house! Mr Edward Lloyd’s establishment was much frequented by mariners and it was here that the great international insurance market germinated. A great gamble on the part of Lloyd’s to commission architect Richard Rogers to create this first great masterpiece of the post-war city, but then if Lloyd’s can’t take a gamble, who can? As well as a perfectly preserved Adam room from Bowood House there are several rooms preserved from the previous 1920s building, and on the outside Rogers has kept the original entrance, a bizarre yet curiously effective conceit.

But the thrills and spills are not over, for opposite is a building that has become the icon of London in the twenty-first century. At night it blazes with intense light, like a rocket about to shoot off to the moon. Londoners, ignoring its majesty, have nicknamed this ‘the Gherkin’ or, even more cheekily, ‘the Crystal Phallus’. The official name is the prosaic Number 30 St Mary Axe (pronounced Simmery Axe) and was commissioned by Swiss Re from Norman Foster and Partners. The same team is also responsible for the wonderful building right next to Lloyd’s rising like a gleaming, metallic Ayers Rock (the Willis Building) and the Millennium Bridge, proclaimed by Foster ‘The Blade of Light’ and by Londoners ‘The Wobbly Bridge’. But the story is not over and the future holds more excitements.

But amid this riot of Modernism there sit, overshadowed in bulk but not in interest, two medieval churches – the old and the new that makes the city so special. St Andrew Undershaft, also on St Mary Axe, gets its name from the maypole that used to stand outside before being broken up by the Puritans as an idolatrous object. Inside is the tomb of the City’s first chronicler, John Stow. His Survey of London has almost never been out of print since 1598 and a copy is given every year to a child who’s written something wonderful about London. The child also gets a quill pen removed from the hand of Stow’s statue in ‘The Ceremony of John Stow’s Pen’, which takes place in early April. The other church is St Helen Bishopsgate on Bishopsgate, so full of monuments it’s been christened ‘The Westminster Abbey of the City’.

Wandering the City at night is a very special experience. The churches may be closed (unless like Lord Burlington you want to take your chances banging on the door) but the sense of atmosphere is incomparable. The lanes are narrow and dark, but don’t worry, they are safe, and you will get lost yet there’s always a pub, or better still an old atmospheric wine bar just around the corner. And when it’s time to go home you won’t be far from a tube station or a bus stop.