SHAUGHAN SEYMOUR

Though not a native Londoner, William Shakespeare made himself in London. And it’s the Bankside area on the south side of the Thames that provides us with so many reminders of the man who gave us a world on the stage. It would be pointless to expand upon the theories about the man and his life, instead let’s look at what is in evidence.

Bankside and the Bard

WE START BY London Bridge, on the river’s south side, where for the most part of 2,000 years there has been a bridge crossing. Because the Thames was narrowed by Victorian engineers the present structure is far shorter than the one the young Shakespeare would have crossed in the late 1580s – then the bridge was 300 metres long (930 feet) long and an impressive feat of medieval engineering. Nineteen arches built on piers called starlings supported the roadway, and piled above were houses, shops, taverns and watchtowers, with a chapel to St Thomas Becket, patron saint of bridge builders, in the centre. Pilgrims on their way to Canterbury would pay the toll, pause awhile on London Bridge, buy a souvenir badge from one of the shops, have a pint of ale and pay their respects to St Thomas in the chapel. They might also have stood by the parapet and watched as boats tried to steer safely between the piers. Going underneath was known as ‘shooting the bridge’, rather like shooting the rapids.

We think 1587 was the year that Shakespeare came to London, having attached himself to a group of players when they performed near Stratford-upon-Avon. London was then a teeming place. Today the City from Tower to Fleet Street houses some 9,000 people. In 1600 the population of the same area comprised some 200,000 souls. London was a magnet for ambitious young men, it was a city where careers could be made and fortunes won. Merchant adventurers were ready to stake thousands on the chance of exploiting the resources of the New World. The population of England had increased dramatically due to a series of good harvests, plague had diminished, and there was more leisure time for the masses. Economist Maynard Keynes made the observation that the country was in just the right financial position to afford Shakespeare when he presented himself.

While the City was a pot of gold for many, there were far more who had to make do with the scraps that fell from its table. Across the bridge and south of the City was Bankside, the playground of the early 1600s. Outside the jurisdiction of the Lord Mayor and Corporation, it was a notorious place, frequented by the young blades of town seeking pleasure in the alehouses, theatres, bull-baiting pits and the ‘stews’ (the houses of horizontal pleasure). Four theatres were established here: the Globe, the Rose, the Hope and the Swan. The very first theatre in London took the original title ‘The Theatre’. Built in Shoreditch in 1576 by James Burbage, a carpenter and travelling player, it stood until 1598, when the freeholder decided to capitalise on the theatre’s success by tripling the rent. On the day the lease expired, the company dismantled The Theatre and slid the timbers across the frozen river, where they were used for the Globe, which was to be the venue for the greatest of Shakespeare’s plays.

WHERE TO READ THIS

There are benches in the garden of Southwark Cathedral; along Bankside by the Globe; and outside the Anchor Tavern. The Globe theatre has a bar with good riverside views, or you could try the Founders Arms.

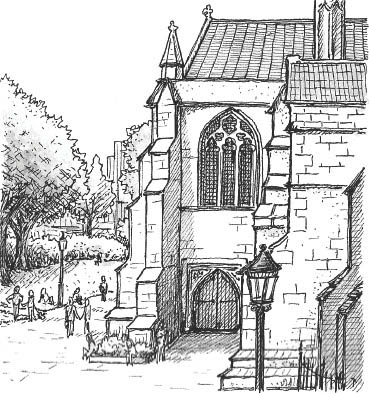

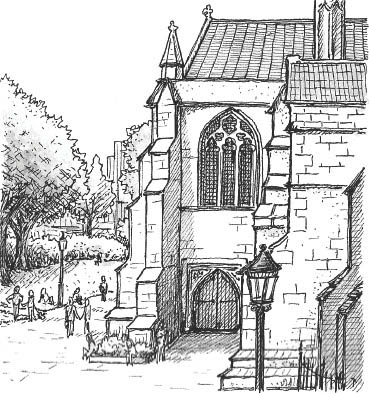

Dominating the south bank area was the parish church now known as Southwark Cathedral. In the seventeenth century it was called St Saviour’s church, and was the earliest church to be built in London in the Gothic style, succeeding the style of the Norman priory church. Shakespeare is recorded as a communicant at St Saviour’s and his youngest brother Edmund lies in the crypt. Not much is known about Edmund but his name appears on some lists of actors at the Globe so we presume his brother helped him secure a job. Records tell us that Edmund died in December 1607, probably a victim of plague. Alongside Edmund lie two contemporaries of Shakespeare – successful playwrights John Fletcher and Henry Massinger, their names inscribed on the floor of the choir.

There are several magnificent memorials in the cathedral and also a small model of the area as it was in the sixteenth century. There is also a memorial figure of Shakespeare, carved in alabaster, above which is the Shakespeare window featuring many of the characters from his plays. Upon occasion a sprig of rosemary is placed in William’s hand ‘for remembrance’ and each 23 April, St George’s Day and, it is thought, Shakespeare’s birthday, a special service is held in the church, with prominent actors performing scenes from his plays and reading his verse.

The church survived the fires that have destroyed so much of what Shakespeare would have known. Ten years after the Great Fire of 1666, a conflagration south of the City destroyed most of Bankside, but another fragment of a building west of the church is a reminder of the presence of the local landlords, the bishops of Winchester. Their great house built in the early 1300s has its west wall still intact, and the latticework of the rose window is still visible. The bishops owned the estate, which included large tracts of parkland, gardens and fishponds in addition to the palace, the refectory and the dormitories for the priory. As landlords, the bishops received rents from some rather dubious sources. Along the riverside were the four theatres, twenty-four taverns and eighteen brothels, or ‘stews’, giving rise to local prostitutes being known as ‘Winchester Geese’. Shakespeare alludes to this in the First Part of Henry VI, when a furious row erupts between Gloucester and Cardinal Beaufort, Bishop of Winchester, with Gloucester calling the bishop a prostitute:

Gloucester: Stand back, thou manifest conspirator … thou that giv’st whores indulgences to sin.

Winchester: Gloucester, thou shall answer this before the Pope!

Gloucester: Winchester Goose! I cry a rope, a rope! … Out, scarlet hypocrite!

Further west from the palace in the area known as the Liberty of the Clink was the Clink prison, a gaol so notorious, so unsanitary and noisome that the term ‘clink’ has entered the language. As the river rose at high tide, water would leak in to the prison, resulting in prisoners having to wallow in filthy water for most of the day. The area was home to various shifty characters – pickpockets, cutpurses, a variety of con-merchants or ‘coney catchers’, and beggars (who were far from destitute), and Shakespeare would have only needed to loiter on street corners in order to pick up a few snatches of conversation. There must have been many a Bardolph or Pistol staggering about, ready to start a quarrel, or a Lancelot Gobbo with his ‘blind’ father, telling a hard-luck tale. The cast of characters was there for the taking.

The Globe Theatre was in Maiden Lane, a polygonal 22-sided building with a thatched roof. Playgoers would queue up at the entrance and drop their pennies into a box, one penny paid for the Pit, or Yard, two for the gallery, three for a cushion. All the boxes were taken to the ‘box office’, where the cash was counted. One penny was a tenth of an average worker’s daily wage then, so pretty good value considering you might be hearing Shakespeare’s words for the first time. Today the new Globe seats 1,500; the original catered for an estimated 3,000. Although on average people were smaller in stature than today, it was still a very crowded auditorium. One gentleman of the period observed at the end of a show at a playhouse, ‘One penny was admittance to the Yard – where the stinkards were so glued together with their strong breath, when they came forth, their faces looked as if they had been boiled.’

On the day of a performance of one of his plays, Shakespeare would have made his way backstage into the tiring house, or dressing room, and met his fellow players. If that day’s play was Hamlet he would have been dressing as the Ghost. Richard Burbage, charismatic tragedian and fellow investor in the theatre, was himself the Prince. The actors’ costumes were the most valuable assets for the company and there were strict rules governing their care and use. If an actor wore a costume outside the playhouse he would have to pay a substantial fine and he would also be fined if he damaged one. The costumes were the main spectacle on stage and patrons would remark on the latest designs. Sometimes the previous year’s court fashions would be recycled and a cloak of a style that had been worn by an ambassador or duke might make its appearance in Twelfth Night or Julius Caesar.

Up close – Shakespeare’s London

At the bottom of Fish Street Hill, across Lower Thames Street in the City stands St Magnus the Martyr church. In the churchyard are two blocks of stone – one white, one dappled grey. The white block is part of the medieval London Bridge – the grey is from the bridge of 1831.

If you walk a short distance to the west of the Globe you will find Rose Alley. When the remains of the Rose theatre were revealed in 1989 during excavation for a new office block, excitement was intense – archaeologists, actors, locals, churchgoers and journalists swarmed around the site like bees. The shape of the theatre became apparent – a fourteen-sided polygon – and in addition the footings of the theatre uncovered, and coins, manicure pins, money boxes and a gold ring unearthed. After a long campaign fought by actors, archaeologists, playgoers and politicians the design of the office block intended for the site was adapted to preserve and include the Rose.

The Rose was the first theatre to be built in the area in 1587. Philip Henslowe was the entrepreneur who saw his chance. He invested £105 in the building, and was later joined by Edward Alleyn, actor and benefactor. This was where Marlowe’s plays were first performed, the likes of Dr Faustus, Tamburlaine and The Jew of Malta; Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part 1 and Titus Andronicus also premiered here, but the Globe, completed in 1599, proved more successful, and the Rose closed in 1605.

In the next alley, Bear Gardens was a different venture altogether. The Davies Amphitheatre, later known as the Hope, was a ringed area surrounded by benches sufficient to seat a thousand spectators. A bear would be chained to a stake, the chain attached to a collar round the bear’s neck. Mastiff dogs were then released, and the fight would begin. People of all ranks loved this brutal spectacle; even Queen Elizabeth, who had a bull- and bear-baiting ring at Whitehall. Bets were placed as to which bear could survive longest or which dog would be the victor. In one instance, it was declared the bear had too much advantage so it had its teeth knocked out and its claws removed to even the odds. The Hope theatre was established in the Bear Garden ring by erecting a stage for the actors to perform. But it lost too much money, the actors were dismissed and the bears brought back.

With an audience made up of merchants, artisans, apprentices, courtiers, country bumpkins and foreign tourists, it would have taken great skill on the part of the playhouse actors to hold their attention. Actors had to have a variety of talents; a good loud speaking voice, and be adept at music, dancing, tumbling and stage fighting. At the Globe, Shakespeare, Burbage and others each held a 12½ per cent stake in the theatre, and the takings were shared out between them and the rest of the company. It was something of a co-operative venture. The Rose and the Hope were local rivals for customers and the output of drama required of the companies was challenging. Sometimes ten plays were put on in as many weeks. Actors were never given the whole script as this would have been too costly, and a complete play could be sold to another company for as much as ten pounds (a labourer’s annual salary). The players were given their lines only, with cues marked to indicate the next speech. The plot was broken down on a list backstage to mark exits and entrances, so it must have been fairly chaotic at the opening performance. If there were problems, one could always rely on the comedians to improvise, though this sometimes caused problems as the clowns would go off the script and do their own songs and dances and deliberately ruin other actors’ moments with mugging and general upstaging.

Shakespeare understood this only too well. When Hamlet gives notes to the players, he pleads: ‘Let your clowns speak no more than is set down for them … for there be of them that will themselves laugh, to set on some quantity of barren spectators to laugh too.’ And yet, without those ‘barren spectators’ Shakespeare would have been missing out on a tidy profit, which is why, even in a tragedy, there has to be a clown. If you take Hamlet, the gravedigger provides us with mordant wit. In Lear, he is the necessary foil for the tragic king, and a clown brings on the fatal asp for Cleopatra.

The theatres were all demolished in the 1640s when the Puritans banned all forms of public pleasure, and the original site of the Globe is now marked with a plaque and some panels giving a short history. Archaeologists have performed ‘keyhole’ excavations on the site and ascertained that the Globe was a large timber-framed building ninety-nine feet across. They also found some trade tokens – coins that could only be exchanged in the alehouses.

The new Globe stands not on the original site but in a prime position on the Bankside, opposite a splendid view of St Paul’s Cathedral. The theatre has proved a huge success, thanks to Sam Wanamaker and all those around the world who raised money, cajoled and persuaded politicians and businesses to sponsor the project. Theatre companies from Africa, Germany, India and Brazil have performed their own versions of the canon here. Fittingly, above the original Globe were painted the words ‘Totus Mondus Agit Histrionem’ or ‘All the World’s a Stage’, and truly the new Globe is a theatre for the world.

Above the new theatre’s entrance is displayed a huge portrait of Shakespeare, in tribute to his legacy. His plays express for us the range of the human condition. He took the twigs and branches of language and storyline and made these flower as no one had done before, or has done since.