BLOOMSBURY: THE HEART OF LITERARY LONDON

BRIAN HICKS

Bloomsbury is like a well-written play. Yes, you can enjoy it on the superficial level of strolling down its boulevards and into its grand squares, but beneath the facades there are layers. Layers filled with stories. The sediments of history lie here behind every block and under every paving stone. When you walk out of Holborn underground station on a bright summer’s day you walk into a manuscript. Glance around at the London planes, their hand-shaped leaves waving to you like so many shades of emerald. These very same trees greeted Virginia Woolf and so many of that group who called themselves the ‘Bloomsberries’. Indeed Virginia, who walked up the nearby Southampton Row, described that street as either ‘as wet as a seal’s back or dappled with red and yellow sunshine’.

Bloomsbury Square

THE AREA OF Bloomsbury is supposedly so called because of William Blemonde, who was given the land in the thirteenth century by the King. He built a house or shelter here, the Germanic word for this being ‘bergan’, eventually becoming the word ‘bury’. This develops into ‘Blemonde’s Bury’ and then like some etymological Chinese whisper into ‘Bloomsbury’.

The family associated with the development of this green-field site, at a much later stage, are the Wriothesleys (pronounced Ris-ley), who have their own literary link of some importance. Henry Wriothesley was the Third Earl of Southampton and was also a significant patron to William Shakespeare. Shakespeare dedicated some of his sonnets to the Earl. It was his son Thomas Wriothesley, not surprisingly the Fourth Earl of Southampton, who in the late 1660s began his development of Bloomsbury Square. This was referred to by his contemporary the diarist John Evelyn as ‘a small town’. Shops were provided for the new inhabitants. The square itself, probably the first in London, was dominated on the north side by Southampton House, later renamed Bedford House when it came into the hands of the Russell family, the Dukes of Bedford. Bloomsbury Square is not far from here, straight up Southampton Row and off to the left, but before you dash to see that, let’s have a look at an extraordinary church built for the new inhabitants of the square in 1730.

WHERE TO READ THIS

You have a choice, either venturing in through the elaborately cast gates of culture into the sacred hallows of the British Museum and finding a quiet spot there, or you could do as Marx himself would do at the end of a busy day and pop into the Museum Tavern opposite the Museum in Great Russell Street. Who knows, you may be sitting in the exact same seat where the ‘father of communism’ sat before you.

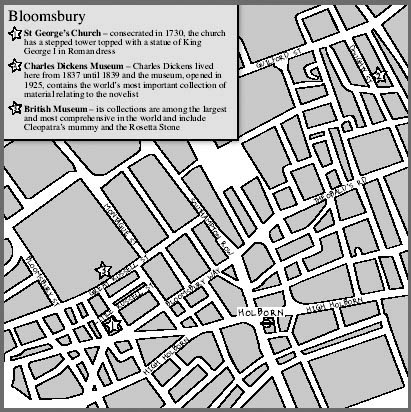

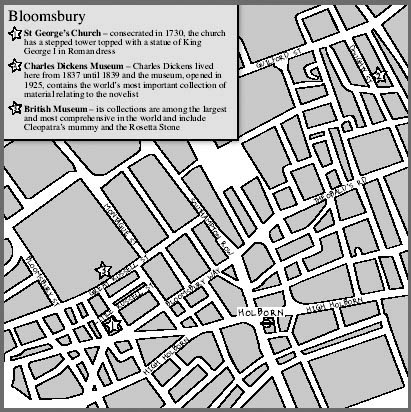

St George’s Church Bloomsbury rests in between Bloomsbury Way and Little Russell Street. A good view of this church may be had from the junction of New Oxford Street and Museum Street. This church was designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor, a baroque architect and pupil of Sir Christopher Wren. Whether it was in fact laid out along some Satanic superhighway as people such as Peter Ackroyd, in his book Hawksmoor, have suggested is debatable, but architecturally this church is a recently restored treasure.

The church was built in response to the demands of the ‘small town’ development. The ladies and gentleman residing in Bloomsbury before its construction had to make their way over to the church of St Giles-in-the-Fields. To get to St Giles they had to brave an area referred to as ‘the Rookery’. This area was filled with prostitutes – ‘the ladies of negligent virtue’ or ‘the daughters of pleasure’ as they became known. As well as this there were many drunks frequenting the vicinity – because of William III’s hatred of the French and his ban on the import of French brandies, ‘genever’, or gin, had become commonplace. It was cheap, and this area became known as ‘Gin Lane’ and is depicted in an engraving of that name by William Hogarth (1751), with St George’s Church in the background. As well as the drunks and prostitutes there were many thieves here – ‘footpads’ or ‘cutpurses’ as they were known. The gentry could not cope with running the gauntlet of these lowlifes each time they wanted to go to church so they petitioned Queen Anne to have their own church built and were granted this privilege under the Fifty Churches Act of 1711.

The oddest feature of this church has to be its steeple. Hawksmoor was ‘inspired’ in his design of the steeple by one of the seven wonders of the ancient world – in this case the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus. Rather conveniently, large parts of that structure ended up in the British Museum just down Museum Street. The Mausoleum had a stepped pyramid surmounting it, so Hawksmoor took that idea, narrowed it down and formed a stepped ‘steeple’. It is truly bizarre and until 1871 it included lions, symbolising England, and unicorns, symbolising Scotland, trying to mount the base of it. After that date they were removed because the stone was becoming unstable. Horace Walpole, who was responsible for a Gothic revival in architecture and literature, saw this church and described it as ‘a masterpiece of absurdity’. When I say ‘Gothic’, in literary terms think here of books like Frankenstein and Dracula; Walpole himself wrote a Gothic novel entitled The Castle of Otranto.

The church was familiar to Charles Dickens, who knew this area well. He lived to the north in Tavistock Square and to the east at 48 Doughty Street, which is now the Charles Dickens Museum. In his Sketches by Boz, Boz being Dickens’s original pen name, you have ‘the Bloomsbury Christening’ taking place in this very church. Mr Kitterbell, who lives at 14 Great Russell Street, brings his son here to be christened. Unfortunately Mr Kitterbell invites his uncle, a miserable man with the wonderfully appropriate name of Nicodemus Dumps. Nicodemus hero-worships King Herod because he kills children, and when Nicodemus makes a speech detailing the dangers faced by a young life he reduces all to a state of misery.

Although that christening is fictitious, it was in this same church in 1815 that the writer Anthony Trollope was baptised. His father was a not very successful barrister who suffered from depression and who lived nearby in Malet Street. His mother Frances Trollope wrote over a hundred books, of which remarkably forty were published. I say remarkably, because they weren’t particularly good. There is only one of her works referred to regularly today. It was entitled The Domestic Manners of the Americans. It was not overly flattering to the people of North America and was considered very irritating by people from that part of the world, but became a bestseller in Britain when published in 1832.

Anthony Trollope joined the post office as a clerk when his father died in 1834. He apparently hated every moment he was there but was ‘posted’ over to Ireland where he worked as a postal surveyor. Although he didn’t actually design the original postbox, it was he who had them introduced as standard around the British Isles (originally they were painted green, not red). To pursue his writing he had to get up at 5.30 a.m. and he tried to write a thousand words per half-hour before he began his working day for the postal service. He wrote two famous series of books. The Barchester Chronicles, including Barchester Towers, deals with the political infighting of the clergy within Barchester, which is a cross between the real towns of Winchester and Salisbury. His second series of books, The Pallisers, includes a book entitled The Prime Minister. Indeed Trollope was the favourite author of former Prime Minister John Major, who was a supporter of the move to erect a memorial to Trollope in Poets Corner in Westminster Abbey. Trollope is not buried there, though – in 1882 he was buried in Kensal Green cemetery. Joanna Trollope, writer of among other things The Rector’s Wife, is a distant relative of Anthony.

In 2006 St George’s Church underwent massive restoration. The American philanthropist Paul Mellon had made a bequest of £4.55 million for the refurbishment of this amazing church. Another £12 million has come from the World Monuments Fund, the Heritage Lottery Fund and English Heritage. The big question was, would they have the money to restore the lions and the unicorns back to their precarious positions? I am pleased to report that the answer was yes! And truly magnificent they look as well. As you look at these creatures, the symbols of England and Scotland, do remember when this church was built – 1730. This was at a time of friction between England and Scotland that led to the Jacobite rebellion of Bonnie Prince Charlie in 1745. It always looks to me as if the lion of England is stalking the unicorn of Scotland – you judge for yourself.

You may also notice that next to the church is a hotel, now the Thistle Bloomsbury but previously called The Kingsley. Named after the author Charles Kingsley, who wrote The Water Babies and Westward Ho!, there is an image of him over the main entrance. The original founders were fond of Kingsley’s stand on morality and alcoholic abstinence. It was here that E M Forster used to stay with his mother Lily when Forster was teaching Latin at the Working Men’s College in Great Ormond Street. He wrote sections of A Room with a View here, not that he was getting much of a view at the time.

The British Museum

If you walk north from the church you will stumble into the great edifice of the British Museum. This internationally famous museum is packed with literary associations. As you stare at the pedimented frontage you are literally looking at the triumph of civilisation. I say literally because that is what is depicted in the pediment. From the crocodile crawling out of the swamp you are drawn to the central figure representing reason.

The museum was effectively founded by a doctor called Hans Sloane in 1753. Hans Sloane came from County Derry in Ireland. He trained as a doctor and became physician to Queen Anne, and later George I and George II. He travelled to the Caribbean with the Duke of Albermarle when he was appointed governor of Jamaica. There he discovered that cocoa mixed with water was prescribed as a curative. He found it ‘nauseous and hard of digestion’, so he mixed it with milk and sugar. It became, not surprisingly, more popular. It was this recipe for ‘Sloane’s’ milk chocolate that was eventually taken over and marketed by the Cadbury family.

Sloane had begun his passion for collecting when a child and it was while in the Caribbean that his collection expanded enormously. He served the Duchess of Albermarle after the death of her husband and was able to set up a successful medical practice just down the road from the present museum at 4 Bloomsbury Place. He married well and during his lifetime purchased collections amassed by many others. When he died, on 11 January 1753, he offered his vast collection that included 50,000 books and 32,000 medals and medallions as well as flora and fauna, maps and manuscripts to the government for a mere £20,000. I say ‘a mere’– but this was when the average annual salary in the country was £5.

His collection was estimated to be worth at least £80,000, so this was still a very generous offer on his part. The collection was bought and shown on this site in a house bought with the help of a national lottery. Montagu House became the base for what was to grow into the British Museum. Over the years many others made donations to this national collection. Edward Harley gave the Harleian collection of books, Robert Cotton gave the Cotton collection of books, King George II gave his ‘Kings library’ – which was an important move because his library was a deposit library and every copy of a book produced in this country had to be deposited here. So it was the library, based here in the museum, which became the great magnet to the writers in the area.

Up close – Bloomsbury

Today, if you want to see the writing desk used by Jane Austen, if you want to see two copies of the Magna Carta, or the beautifully illuminated Lindisfarne Gospels, or listen to the voice of Virginia Woolf, or see the handwritten songs of the Beatles, it’s up to the new British Library at St Pancras you go and to the free exhibition they have there.

By 1855 Montagu House was too small, so it was demolished and Robert and Sydney Smirke built the great structure that stands before you today. In the centre of this building there was a garden, so you could stroll and get fresh air. By 1857 they realised they needed that space as well, so a man called Antonio Panizzi designed a domed reading room to be the heart of the library. It was based upon Hadrian’s Pantheon in Rome. All the rest of the garden space became used up by buildings associated with the library and the storage of books.

Then in 1970 it was decided to move the library elsewhere and this was finally done in 1998 when the new British Library was born up at St Pancras.

Now in the normal course of events anyone can go into the old Reading Room. In the past you had to have one of the coveted ‘Reader’s tickets’ and show you were doing research. Charles Dickens acquired his when he was 18 years of age (normally you had to be 21 but he was working as a journalist so he got his early). Oscar Wilde had his reader’s ticket withdrawn when the scandal came out about him in 1895 and Sherlock Holmes also had a reader’s ticket – well, a fictional one, anyway. (Apparently, in a recent survey, 58 per cent of people asked thought Holmes was real. Presumably it was this same group of whom 25 per cent believed Winston Churchill was a fictional character.)

A few years ago Mikhail Gorbachev was being shown around in the Reading Room and he apparently stopped his tour guide and said, ‘This is the birthplace of communism.’ Karl Marx was a reader and wrote Das Kapital here in rows J–P. Trotsky said he ‘gorged himself on books’, there were just so many books to read, and Lenin registered as a reader under yet another false name. Under the name of Jakob Richter he would write articles in seat L13 for a magazine called Iskra. When he wasn’t doing this he would also act as tourist guide and show other exiles around the area. Guides can be a radical lot.

It was the reading room and library which was the draw to many other writers as well, including Rudyard Kipling, Mahatma Gandhi when he was a law student at University College and Inner Temple, George Orwell and George Bernard Shaw. Also H G Wells, Virginia Woolf, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Joseph Conrad, Arnold Bennett, W B Yeats, Thomas Hardy, E M Forster, Agatha Christie, Thomas Carlyle, Algernon Swinburne and Edward Gibbon, to name but a few.