BRIAN HICKS

When you are spewed out of the underground station at Sloane Square you emerge into a genteel world. Sweaty bodies give way to scented silk scarves wantonly sprayed by wealthy ladies who ‘shop’. Gentlemen here do not push and shove, but give way with polite gestures of their delicately manicured hands. That breed dressed in a uniform of Burberry and Barbour, known as ‘Sloane Rangers’, may be all but extinct but their good manners and courtesy still survive in petite, well-tailored pockets of Chelsea. Chelsea has not always been so tasteful. Its fortunes have ebbed and flowed with the tides of the nearby Thames.

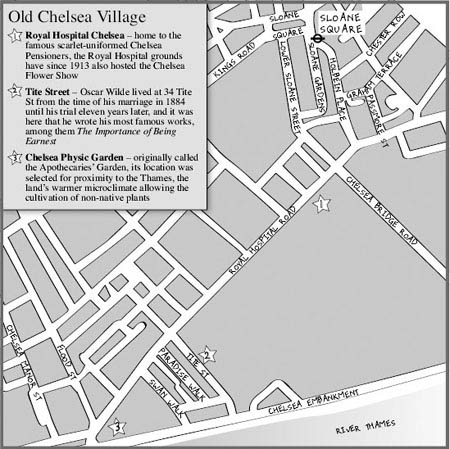

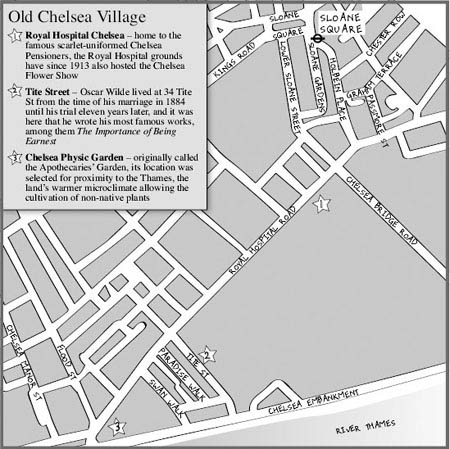

Sloane Square and the Royal Court

THE CHELSEA STORY begins with those ruffians who established so many English towns and settlements – the Anglo-Saxons. No perfumes for them. No shopping. They took what they wanted and they took this land from the Celts. Their settlement was a landing place, a hithe or hethe, built on chalk, chele in Anglo-Saxon. So this becomes Chele-hethe, synthesised over the centuries to ‘Chelsea’.

The subsequent village founded by them became known, in the sixteenth century, as the ‘village of palaces’. Its location, so close to the medieval motorway of the Thames, made it a convenient stopping-off place for the wealthy when they ventured up- or downstream with the assistance of a benign tide. King Henry VII had a house here, so did the Earl of Shrewsbury and his wife Bess of Hardwick. The Bishop of Winchester resided here and so did the saintly Lord Chancellor, Sir Thomas More.

In the early seventeenth century Chelsea was dominated by one man. His legacy permeates the very air of this district. The station, the square, the streets bear his name. He was Hans Sloane. He was born into the Restoration in 1660. His family were wealthy. Hans studied in London and Paris and became an accomplished physician. He attended Queen Anne and her successors and he was appointed president of the Royal Society, remaining so for twenty-six years. In Chelsea he was responsible for ensuring the survival of the Society of Apothecaries’ Physic Garden. His collection formed the foundation of the British Museum. To his daughter Elizabeth he left his Chelsea property of over a hundred acres. She in turn married Lord Charles Cadogan and, as you will gather if you stroll around here, the Cadogans are still around. The current Lord Cadogan is one of the country’s wealthiest people, primarily because of his land holdings here. So Hans’s family still have a firm grasp of his estate.

WHERE TO READ THIS

The Fox and Hounds pub, at the corner of Graham Terrace and Passmore Street: to say this is an intimate pub is a bit of an understatement. The pub is now twice the size it was and it is still remarkably small. It was created to cater for servants from the local big houses. It dates from 1830 and has a select clientele, including the odd monk, but it is peaceful and friendly. So get yourself a pint of Young’s ‘Dirty Dick’ and have a read. An alternative is to enter the Chelsea Physic Garden and find yourself a shaded bench. The garden has a delightful tea room, so if the time is right perhaps you should also treat yourself to one of their wonderful cakes and a pot of Darjeeling.

The boundary for Chelsea was almost completely aquatic, to the south the Thames, to the east the River Westbourne and to the west the Counters Creek. The northern boundary was the Fulham Road. These boundaries have been tampered with most prominently here under your very feet. Arriving by train you may have glanced up and seen a large structure scaling the platforms, studded, boxed and contained. Contained because within this structure is the rather sad remains of one of London’s lost rivers, the Westbourne. One-time boundary and trout stream but now reduced to the function of a sewer. In more refined days Sloane Square station was one of only two complete with a bar. This bar was called ‘Drink Under the River’ because that’s exactly what you would do.

Outside the station your eye may well be caught by the Royal Court Theatre, founded in 1888. Chelsea has always been popular with ‘theatricals’. Actors and writers abound and the ‘court’ has been associated with experimental and avant-garde theatre. Shaw premiered plays here. George Bernard Shaw was an influential ‘Fabian’, a socialist, who mixed with such people as H G Wells and Sidney and Beatrice Webb. His socialist beliefs underpinned most of his writing. He could be an old rogue. He said of himself he was an ‘immoralist and heretic’. Sometimes grumpy but always witty, once at a party he was asked, ‘Are you enjoying yourself, George?’ His reply was the rather cutting, ‘Well, there is nobody else here to enjoy.’

Shaw’s plays have had many performances here at the Royal Court. St Joan, Heartbreak House and Back to Methuselah all premiered here in the 1920s. The theatre became a cinema in 1935 and remained so until it was bombed in 1940. When the building was restored in the 1950s it became once again a theatre and it was here that the angry young man John Osborne premiered his plays such as Look Back in Anger and The Entertainer.

If you leave the square and make your way down one of the side streets such as Holbein Place or Lower Sloane Street you will eventually bump into the Royal Hospital in Royal Hospital Road, the home of the Chelsea Pensioners. You don’t have to be sick to come to this hospital, but you do have to have served in the army. ‘Hospital’ in this instance relates to ‘hospitality’. The hospital has a proud history that stretches back to its famous founder, King Charles II.

Charles was a tall man, over six feet in height with a dark complexion. He was physically fit, a good swimmer and rower. By all accounts he could be charming and lovable. He was a born pragmatist and would always work to his own strengths. He had learned a hard lesson from his father Charles I, who had been executed in 1649 for his autocratic style and his abuse of Parliament. After a civil war fought by the Parliamentarians against the Royalists, the King was beheaded and England became a Puritan Republic termed the ‘Commonwealth’. The eventual head of state was one Oliver Cromwell, a man who lacked vanity, and who saw the world for what it was, ‘warts and all’.

The young Charles II was forced to live abroad, most notably at the court of his cousin Louis XIV of France. While at the ‘Sun King’s’ dazzling court in Paris he promised he would convert to Catholicism if he should become King of England, and he also noticed that Louis had provided a retirement home for old soldiers called Les Invalides.

When Charles was restored to the British crown in 1660, it was with the help of the British army and a man called General Monk. Charles decided it might be politic to show his appreciation to the army, and what better way to do this than to set up a grand retirement home for old soldiers, based upon the French model. It was founded in 1682. Charles apparently donated some £7,000 to help towards its establishment and was able to get the finest architect in the land to construct the dining hall and chapel wings – none other than the designer of St Paul’s Cathedral, Sir Christopher Wren.

Charles is quite rightly celebrated here. In the quadrangle there is a fine statue by Grinling Gibbons, more renowned for his woodcarving than his sculpture. This bronze was gilded to commemorate the present Queen’s Golden Jubilee in 2002. Apparently some, even among the ranks of the Pensioners, think it now looks rather gaudy.

The statue is the focus of Oak-apple Day, 29 May, Charles II’s birthday. On this day each of the 350 or so ‘Boys of the Old Brigade’ march up to the statue armed with a piece of oak branch. They place these around the statue until the King lies hidden in the oak leaves. The ceremony commemorates the escape of Charles II from the Parliamentarians in 1651 after the Battle of Worcester. Charles II had been defeated by Oliver Cromwell and had to escape. He made his way to Boscobel House in Shropshire. The Penderel family were loyal to the King but felt it was unsafe for him to reside in the house so he slept in an oak tree in their grounds, attended by Colonel Carlis and a cushion. While Charles hid in the tree, Cromwell’s men came and searched the house and, according to legend, when they went outside and stood under the very oak tree which shrouded the King, the soldiers began talking about what they would do if they laid their hands upon his person. Charles escaped and enjoyed recounting that story again and again. It is recorded in the diary of none other than Samuel Pepys. Oak-apple Day became a public holiday celebrated throughout the land right up until the nineteenth century, and is still remembered in some other places in Britain even today. Numerous public houses remember that ‘Royal Oak’ in their names and the Pensioners get double rations on Oak-apple Day.

Oh, and about that promise to Louis XIV about converting to Catholicism if he was restored to the English crown … well, Charles, ever the pragmatist, realised that this would be a very unpopular move with the British people, but he wanted to keep a promise made in good faith – so he converted to the Catholic faith on his deathbed in 1685.

Up close – Chelsea

The building of the Albert Bridge in 1873 coincided with the construction of the Chelsea embankment. Designed by Rowland Mason Ordish, the bridge’s delicate design is similar to a bridge – the Franz Josef bridge – Ordish designed to cross the Danube and which was demolished in 1949. The Albert Bridge was decked out in lights for the Festival of Britain in 1951 and they have stayed ever since, making it a glittering spectacle on the Thames. One local who loved the bridge was John Betjeman, poet laureate and architectural writer. When the bridge was under threat in the 1950s he formed a protest group to save it – one of the earliest architectural ‘conservation campaigns’. The bridge has a sign on it dating from the Second World War which advises soldiers to break step when marching across the bridge.

Just around the corner from Royal Hospital Road lies Tite Street, whose most famous resident was Oscar Wilde. He lived at No. 34.

Oscar was the son of a baronet and eye surgeon in Dublin. His mother Jane Wilde was a nationalist and poet published under the name of ‘Speranza’. Oscar went to Trinity College Dublin and then subsequently to Magdalene College, Oxford. Students at Trinity like to say that he was ‘sent down to Oxford’. Wilde graduated from Oxford with a double first and soon after met Constance Lloyd, whom he married. They moved into this house where he wrote in the ground-floor studio on a desk that had belonged to Thomas Carlyle. In 1884 he met Lord Alfred Douglas, or ‘Bosie’ as he was known, and almost immediately there was a spark of attraction between the two men. This became common knowledge in London and one person who found out about this was Bosie’s father, the Marquess of Queensbury (the man who drew up the rules of boxing). The Marquess believed there was something ‘going on’ between his son and Oscar, so he came down to Tite Street, barged in through the front door and threatened Oscar in his own family home. Oscar apparently said to his servant, ‘This is the Marquess of Queensbury, the most infamous brute in London; never allow him into my house again.’ The Marquess did not stop there; he made his way up to Wilde’s club, the Albermarle just off Piccadilly, and there he left his famous calling card with the words inscribed upon it, ‘To Oscar Wilde posing as a somdomite’. Apparently he couldn’t spell. When Oscar saw what was written upon the card he was quite calm, but Bosie was mortified. After much encouragement from Bosie, Oscar went along to his lawyers to begin an action for defamation against the Marquess. He lost the trial and was later charged with gross indecency. After what many regard as a show trial he was imprisoned in 1895. He was released in 1897, left England and never returned. Wilde died on 30 November 1900 in Paris, his last words supposedly, ‘Either that wallpaper goes or I do!’ The blue plaque on his house was put up in 1954, the centenary of his birth. One local magistrate was apparently against this ‘honour’, stating that Oscar was nothing but ‘a common filthy criminal’.

Back into Royal Hospital Road and to the Chelsea Physic Garden. Established in 1673 by the Society of Apothecaries, its purpose was to grow plants to be used as medicines for ‘physicians’, thus the name. It is not the oldest physic garden in Britain – the Oxford Botanical Garden dates back to 1621 – and it is certainly not the oldest physic garden in Europe, the first physic garden being formed in the university city of Pisa in about 1543. Nevertheless this is a very significant garden and more than a hundred years older than the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew.

During the later part of the seventeenth century one visitor was the diarist John Evelyn. He was fascinated by the ‘subterranean’ heaters used to keep the plants alive during the very cold winters of this period. Carolus Linnaeus came here to study plants. A seed exchange was established here in the seventeenth century. The first Cedar of Lebanon trees in England were grown here. John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist Church, visited in 1748 while, later, Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon visited the garden to escape the hell of the First World War. The garden still has links with Imperial College, part of the University of London, and studies have been done here on the Madagascar periwinkle, from which is derived an alkaloid used in the treatment of leukaemia, and the woolly foxglove, with reference to digitalis used in the treatment of heart conditions.

When Hans Sloane became the Lord of the Manor here in 1712, this land became part of his estate. The Society of Apothecaries had wanted to purchase the land to secure it but Sloane instead agreed that he would rent it to them at £5 per annum. Another condition was that they should send to the Royal Society five specimens of dried plant per year until this august body had received two thousand specimens. Hans was president of the Royal Society himself for twenty-six years and this collection of plants not only ensured the continuing study of plants here but also forms part of the collection of the Natural History Museum today.

The garden became a registered charity in 1983. Annual rent still has to be paid to the successors of the man who gave the station where we began our visit its name, Hans Sloane. A cheque has to be written out to the Cadogan Holding Company, still for the sum of £5. The cost of entry today is £7, so with one visitor they have paid their rent for the year and have a £2 surplus. Now that has to be the way to run a business.

Chelsea has a lot to thank Hans Sloane for.